Selfie Culture Lacks Self-Awareness

Recently, a female skier in China was rescued from a mountaintop after being seriously injured in an attack by a snow leopard. But this was no random attack. The tourist, upon spotting the rare animal on her drive back to her hotel, somehow decided that it would be a good idea to get out of her car, approach the animal, and take photos. In video footage, she is seen lying motionless in the snow with the predator nearby. She was taken to the hospital, and it is believed her ski helmet saved her life. Apparently, the woman was credulous enough to believe that an unpredictable wild animal might take a break from its hunt for an Asiatic ibex to pose for a selfie with her.

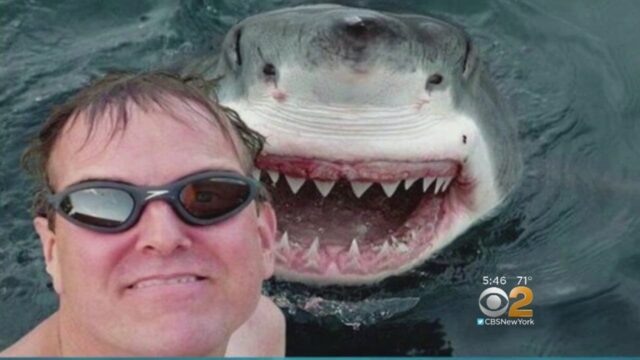

Such reckless behavior is symptomatic of the attitudes that are all too prevalent in our modern era. The desire for validation, amplified by the dopamine hit of likes and retweets on social media, drives people to seek dangerous locations to capture that unique selfie. Unfortunately, this trend is swiftly thinning the gene pool. In recent years, selfie-related deaths have sharply increased—one study documented over 379 between 2008 and 2021, and by the end of 2024, the toll may well have reached 480. On average, 43 people die each year from selfie-related incidents. To put this in perspective, selfies kill far more people than shark attacks, which average just six deaths per year worldwide, but still manage to keep plenty of people on alert while enjoying a day at the beach.

Technology has transformed our behavior, turning what was once a communal spirit of adventure into malignant narcissism. As Jonathan Haidt notes in his book The Anxious Generation, this shift began in 2012 with the introduction of the front-facing smartphone camera. In 2014, Android users took 93 million selfies each day; by 2025, that number across all devices had soared to 5.3 billion—a staggering 5,600 percent increase.

The exponential rise in selfies taken under dangerous conditions, however, reflects the increasingly foolish ways people seek attention, often resulting in tragedy. In 2015, 32-year-old Spaniard David González Lopez was gored to death while trying to take a selfie in the midst of a running of the bulls festival in Toledo. The next year, Jia Lijun tried to snap a photo with a 1.5-ton walrus at a wildlife park, but the animal, uninterested in being a social media star, dragged him into a pool, drowning both Lijun and a zookeeper who tried to help. In 2024, Prahlad Guijar was mauled to death attempting a selfie with a lion. When not killing themselves, selfie-takers are ruining things for everyone else: During the 2023 Tour de France, a spectator caused a 20-rider pile-up by stopping to take a selfie.

Once upon a time, people took photos to capture cherished memories—events, snapshots of loved ones, or breathtaking vistas of snow-covered mountains. Now, with the rise of selfies, no scene feels special unless you plant your own face in every picture. This digitally disconnected self, however, is managing to pull us ever further from reality. We live in an age of curated “prolificity”—a false, inauthentic digital identity, an avatar that exists vicariously through online interaction and the adulation of strangers.

Traditionally, sharing was an outward-looking and outward-directed activity. The very definition of sharing was “to give some of what you have to somebody else.” In recent years, however, sharing has become more inward-looking. Merriam-Webster now defines sharing as “to talk about one’s thoughts, feelings, or experiences with others.” This modern definition reflects the secular confessional culture of the 21st century.

This desperate, almost childlike craving for attention is a regrettable fact of modern culture. It is driven by another repulsive affliction of our time: main character syndrome. This is the narcissistic, solipsistic belief that, in any situation, you are the protagonist in a presentation of your life’s story and everyone else exists solely to help you tell it and inflate your rampaging ego.

Many thinkers have noted a marked decline in Western culture over the past 25 years, remarking on how its creativity and originality appear to be all but extinguished. Given the self-obsessed developments of our time, it is no surprise that our output is often stale, starved of creativity, and didactic. Trapped in this cultural dark age, we urgently need a guiding light to show us the way out—a spark to reignite imagination and purpose.

In the early 20th century, the Futurists advocated war as a means to revive culture. In 1909, the Italian Futurist, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, published his “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” in the French publication Le Figaro, in which he urged the destruction of museums to purge Italy of the “fetid cancer” of its past. Today, as Neil Postman observed, we are Amusing Ourselves to Death, too distracted to challenge the cultural hegemony that sustains stagnation. In that condition, all talk of a culture war is pointless. Not even vandalism—whether conducted by ISIS destroying churches or eco-zealots targeting classic works of art—appears to do anything to spark true cultural revolution.

A firestorm won’t cleanse the world of this cultural void. Silicon Valley’s technopoly has created a passive, apathetic society. Last year, over 2 trillion photos were taken globally, and about 5 percent of them were selfies. If you want to experience reality, unplug from the matrix—leave your phone behind and go outside. Touch grass and set about looking for goodness, beauty, and truth in something other than yourself.

https://chroniclesmagazine.org/web/selfie-culture-lacks-self-awareness