China and the Western Hemisphere Post-Maduro

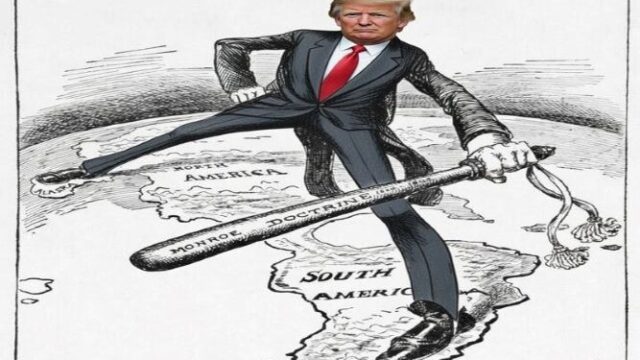

The capture of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by US military forces has turned the theory of a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine into a reality that cannot be ignored by so-called non-Hemispheric competitors who have over the course of the past decades positioned themselves economically in the Western Hemisphere. For China, which has invested heavily in bringing its Belt and Road Initiative to the doorstep of the US, this new policy stance spells nothing but trouble.

In May 2025, China hosted Latin American and Caribbean leaders at a summit in Beijing, where Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a $9 billion investment credit line for the region. China was doing more than simply sustaining an investment campaign driven by the dynamic of the global Belt and Road Initiative, a massive multitrillion-dollar global infrastructure development program that has been at the heart of China’s foreign policy for more than a decade. The reelection of Donald Trump brought with it concerns that he would be implementing punishing tariff-based economic measures that China believed (and hoped) would push Latin and South American nations toward China and away from US economic hegemony.

China was building upon an economic foundation that was a product of over two decades of sustained economic growth and influence in the region. In 2000, China accounted for less than 2% of the Latin American export market. By 2024, China-Latin America trade topped $518 billion, making it the region’s second-largest trade partner after the US and the leading trade partner for several major South American economies. This level of business brought with it other mechanisms of influence — large Chinese diaspora communities have sprung up in Brazil, Cuba, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela.

The $9 billion investment credit line China extended in May 2025 was predicated on the anticipation of new economic growth opportunities triggered by a negative reaction to Trump’s economic bullying. China, after all, had ridden out the previous Trump administration’s anti-Chinese bluster. There was little expectation among the senior Chinese leadership that the second coming of Trump would produce a different result.

A New World Order

Trump’s second term, however, has been marked by a decisive embrace of a transformational foreign and national security posture that eschews the traditional rules-based international order that served as the foundation of US policy in the decades following the end of World War II and instead focuses on a retreat from legacy commitments to secure far-flung corners of the world while focusing on the creation of a “fortress America” anchored in a Western Hemisphere dominated by the US politically, economically and militarily. The US, under Trump, isn’t looking to outcompete nations in its backyard; it is looking to expel non-hemispheric competitors altogether.

“After years of neglect,” the Trump administration declared in its 2025 National Security Strategy (NSS) that the US “will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere, and to protect our homeland and our access to key geographies throughout the region. We will deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets, in our Hemisphere.”

The Trump administration has effectively sought ownership of the entire strategic resource potential of the Western Hemisphere, declaring these resources to be within an exclusive US-only sphere of interest in which no competition will be tolerated or permitted. The capture of Maduro and intent to assert control over Venezuela by the Trump administration appears to be but the opening salvo of what will be the aggressive implementation of the policy objectives associated with the creation of Trump’s “fortress America.”

The US, the 2025 NSS declares, “must be preeminent in the Western Hemisphere as a condition of our security and prosperity — a condition that allows us to assert ourselves confidently where and when we need to in the region. The terms of our alliances, and the terms upon which we provide any kind of aid, must be contingent on winding down adversarial outside influence — from control of military installations, ports and key infrastructure to the purchase of strategic assets broadly defined.

This policy direction does not bode well for China and the investments it has made in Latin and South America over the past two decades.

On the Back Foot

Unfortunately for China, it has little recourse when it comes to countering Trump’s aggressive embrace of the Monroe Doctrine. China’s position in the Western Hemisphere was always conditioned on the realities of the rules-based international order in which China played the game better than its US competitors, and as such centered on economic competition.

The Trump administration, however, has dramatically redefined the rules of the game, leaving China virtually checkmated when it comes to implementing an effective response. The game, in the US’ eyes, is now defined less by the size of the investments a nation is willing to make in a given region and more by the size of the military commitment it can allocate to secure the resources and infrastructure of this same region.

And when it comes to the Western Hemisphere, China is outmatched by the US in both the military and economic spheres, including in Latin America, where China has made significant — strategic — economic investment. The military gap is significant, not surprisingly given China’s focus on Asia. Whereas the US has unmatched capacity to project decisive military power anywhere in the Western Hemisphere, China has far more limited capacity to project and sustain military power in the Western Hemisphere, having no comparable basing network or logistics architecture and limited ability to conduct sustained operations at extreme distance.

Moreover, in accordance with the policies promulgated under the 2025 NSS, the Trump administration is preparing to tie China down militarily and economically in its own backyard, making China worry more about who controls Taiwan than who controls Chancay Port in Peru.

Again, the 2025 NSS states: “A favorable conventional military balance remains an essential component of strategic competition. There is, rightly, much focus on Taiwan, partly because of Taiwan’s dominance of semiconductor production, but mostly because Taiwan … splits Northeast and Southeast Asia into two distinct theaters. Given that one-third of global shipping passes annually through the South China Sea, this has major implications for the US economy. Hence deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.”

It is the Trump administration’s goal to tie China down in a regional power struggle, leaving China with less capacity to respond to the US land and resource grab in Latin and South America. The US will likewise seek to leverage the overwhelming advantage it has accrued through decades of trade dominance with its Western Hemispheric neighbors, even if built on bluster — as when Trump threatened to impose crippling tariffs on Canada if it signed a free trade deal with China, which it was not in fact pursuing.

“You cannot live within the lie of mutual benefit through integration,” Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney recently stated in a speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, “when integration becomes the source of your subordination.”

The problem for Carney and all the other leaders of Western Hemispheric nations is their vulnerability to the will and whim of the US through its economic and military might. The notion of “Fortress America” — or at best an unreliable America — is a reality that China and the Western Hemisphere will have no choice but to live with for the foreseeable future. But the risk for the US is that such tactics continue to drive governments in the region to diversify away from the US and toward China and other economic and security partners.

https://www.energyintel.com/0000019c-282e-d184-a3fc-acae3c020000