Because He Was White

Four British boys were selected, attacked, and killed for no reason other than their race.

There are murders that galvanise a nation, like that of the criminal thug George Floyd, and there are murders that pass almost unnoticed, absorbed into the background noise of urban violence. This article is about the second kind. About boys whose suffering and death was not elevated into British national reckoning, and whose killers’ motives were acknowledged in court but rarely allowed to shape public discourse or understanding. What unites the cases that follow is not only brutality, but a shared and unambiguous fact: each victim was targeted because he was white.

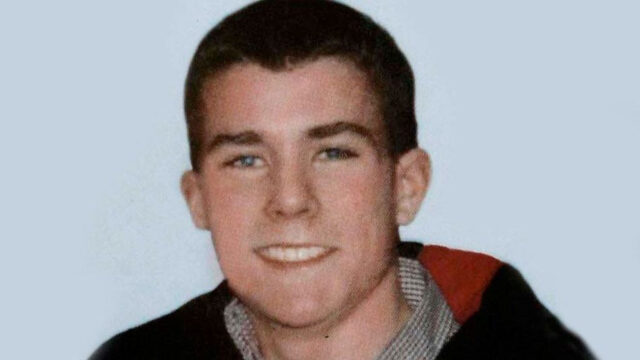

The Execution of Kriss Donald

The murder of fifteen-year-old Kriss Donald in March 2004 remains a watershed moment in Scottish criminal history. Yet, despite the sheer brutality of the crime, its place in the national consciousness is strikingly muted when compared with other high-profile tragedies.

On the afternoon of 15 March 2004, Kriss Donald was walking along Kenmure Street in the Pollokshields area of Glasgow with a friend.1 He was an ordinary schoolboy, with no involvement in gang activity, no history of violence, and no connection to any racial dispute. His abduction was an act of pure substitution. He was taken solely because he was a “white bastard” who happened to be available to satisfy a gang’s desire for retribution.2

The Pakistani gang, led by Imran “Baldy” Shahid, had been seeking revenge after Shahid was struck with a bottle at a nightclub the previous evening.3 When they failed to locate those responsible, the gang resolved to abduct the first white male they encountered.4 Kriss Donald was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The terror of Kriss Donald’s final hours unfolded as a 200-mile odyssey across Scotland. After being forced into a silver Mercedes, an abduction witnessed by his friend, who was himself assaulted, Kriss was driven from Glasgow to Motherwell, then to Dundee, and finally back to Glasgow.5 Throughout this journey, he remained at the mercy of his captors, subjected to sustained psychological torment. His plea, “Why me? I’m only 15” captured both the innocence of the victim and the arbitrary cruelty of his selection. One of the men responded to his pea with “white bastard, do you know what pain is?”6

His abduction was a prolonged period of captivity that revealed a total absence of restraint, empathy, or recognition of Kriss Donald’s humanity by those who held his life in their hands.7

The killing itself took place on a secluded walkway near the River Clyde in Glasgow’s east end.8 The violence inflicted on the boy was later described by Lord Uist as “savage and barbaric.”9 Kriss was stabbed thirteen times across his stomach, back, and arms.10 Yet even this was not enough to kill him.

While he lay wounded, bleeding, and unable to escape, the gang poured petrol over his body and set him alight.11 Forensic evidence later confirmed that Kriss was alive and conscious when the fire was ignited.12 Marks at the scene showed that he had attempted to roll along the ground in a desperate effort to extinguish the flames.13

His body was discovered the following morning, curled into a foetal position, charred and partially clothed.14 The manner of his death, conscious, prolonged, and inflicted with deliberate cruelty, places this crime among the most extreme acts of inhumanity recorded in modern British history.

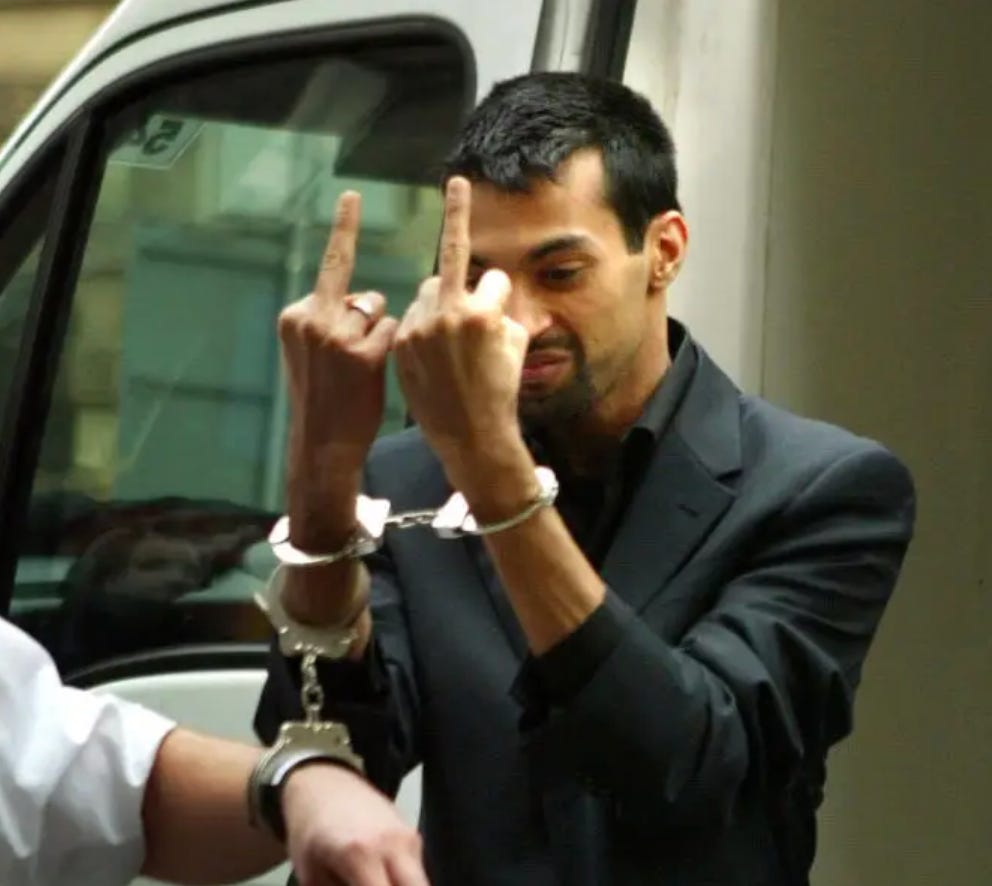

Following the murder, three of the primary suspects, Imran Shahid, Zeeshan Shahid, and Mohammed Faisal Mushtaq, fled to Pakistan to evade prosecution.15 This initiated a complex geopolitical struggle known as Operation Boxer.16 At the time, no extradition treaty existed between the UK and Pakistan, creating a significant legal vacuum. The diplomatic effort to secure their return was led a by local MP, who lobbied Prime Minister Tony Blair and Pakistani officials.17

The suspects were eventually arrested in Pakistan in July 2005 and extradited in October 2005 under a groundbreaking, one-off agreement.18 The handover occurred at Islamabad Airport, where the men were transferred to Strathclyde Police officers in handcuffs and chains.19 While heralded as a triumph of justice, the process revealed the immense hurdles faced when pursuing perpetrators of anti-white violence who possess transnational ties.

The Murder of Ross Parker

The murder of Ross Andrew Parker in September 2001 offers another harrowing example of anti-white violence defined by random selection and ritualised cruelty. Occurring just ten days after the September 11 terrorist attacks, the killing unfolded against a backdrop of heightened global anxiety and localised racial tension in the Millfield area of Peterborough.20

Ross Parker was seventeen years old and worked as a bar assistant. In the early hours of the morning, shortly after 1:15 a.m., he was walking home with his girlfriend, Nicola Toms.21 They were intercepted on a cycle path by a group of approximately ten Pakistani youths, several of whom were wearing balaclavas.22 Witnesses and investigators later described the group’s behaviour as that of a “hunting party” or a “mission,” rather than a spontaneous altercation.23

After taunting Ross and telling him that he “better start running,” the group deliberately blocked his escape route.24 He was sprayed directly in the face with CS gas, blinding and incapacitating him.25 What followed was a coordinated assault. While Ross lay defenceless, he was punched, kicked, and struck repeatedly with a panel beater’s hammer.26

The attack culminated in the use of a foot-long hunting knife, which was driven into Ross’s throat and chest.27 Forensic evidence later established that the wound was so severe it “split the whole of his neck open.”³ Nicola Toms, who had run to seek help, heard Ross’s final cries as he bled to death on the path.28

The psychological state of the attackers was laid bare during the trial through testimony concerning their conduct in the aftermath of the killing. The gang regrouped at a garage they referred to as a “den,” where Ahmed Ali Awan raised the bloodstained hunting knife and declared to the others: “Cherish the blood.”29 Obviously, this statement was not uttered in panic or confusion, it was said as an expression of triumph. When read alongside the established fact that the group had deliberately set out to find “a white male to attack simply because he was white,” it reveals the depth of racial animus that animated the crime.30

The national media response to Ross Parker’s murder quickly became a subject of controversy. Critics argued that the BBC and other major outlets markedly downplayed the racial character of the crime.31 While contemporaneous murders of ethnic minority victims often generated sustained national attention and explicit discussion of motive, Parker’s killing was frequently confined to local reporting or recast in more neutral terms as “gang violence.”32 This reframing had the effect of stripping the crime of its defining feature, rendering its racial intent incidental rather than central to public understanding.

The BBC later issued an apology for its handling of the case, acknowledging that its reporting had been inadequate when measured against the coverage routinely afforded to cases in which the victims were from non-white backgrounds.33 This admission lent institutional weight to what critics had long argued, that a persistent double standard exists in the recognition of victimhood. For many on the right, the episode confirmed a broader reluctance within the British establishment to acknowledge white victims of racial violence with the same clarity, urgency, or moral emphasis.

The Murder of Richard Everitt

The 1994 murder of Richard Norman Everitt in Somers Town, London, illustrates the concept of “substitution” in racial violence. Richard was a 15-year-old described as “well-liked” and “mild-mannered,” who became the victim of a gang seeking revenge for an incident in which he played no part.34

Somers Town in the mid-1990s was a site of significant ethnic friction. The area had suffered from urban decay, and the white working-class population felt increasingly marginalised by social housing policies that were favouring Bengali immigrants.35 This resentment was strongly mirrored by the Bengali community, leading to a volatile environment where any spark could lead to violence.36

On the night of 13 August 1994, a gang of Bangladeshi youths from Euston entered Somers Town seeking revenge against an Irish teenager named Liam Coyle.37 Unable to find Coyle, the gang resolved to target any white youth they encountered. The prosecution characterised the gang as a “danger to any vulnerable white youth”.38 Richard Everitt, returning from playing football and buying food with friends, became that target.39

Richard was chased and stabbed in the back with a seven-inch kitchen knife, which pierced his heart.40 Under the legal doctrine of “joint enterprise,” Badrul Miah was convicted of conspiracy to murder and sentenced to life with a minimum of 12 years, although it was never conclusively proven that he was the one who wielded the knife.41

The impact on the Everitt family was devastating, and it was compounded by the environment in which they were forced to grieve. In the aftermath of the convictions, the family was subjected to sustained abuse from Bengali neighbours, ultimately driving them to leave London altogether.42 Richard’s mother, Mandy Everitt, later observed that she sometimes wished her son had been killed by a white boy, because then she would have had to endure only the loss itself, rather than what she described as the “nightmare of everything else.”43 By this, she was referring not only to her bereavement, but to the racial politics, hostility, and perceived institutional indifference that followed the murder.

Even the physical memory of Richard Everitt was handled with a striking lack of care. In 2020, Camden Council removed his memorial bench and plaque without informing the family.44 It was not until 2024, three decades after the murder that a replacement memorial was finally installed.45 The neglect surrounding Richard Everitt’s commemoration stands in sharp contrast to the permanence and national reverence afforded to other victims of racially motivated violence.

The killing of Gavin Hopley

The death of Gavin Hopley in Oldham in February 2002 stands as a overt example of the British justice system’s failure to deliver accountability in a case of anti-white violence, particularly within an area shaped by de facto “no-go zones” and the legacy of recent racial unrest.

Gavin Hopley was nineteen years old and from Heywood. He was in the Glodwick area of Oldham with two friends when they became disoriented while searching for a taxi.46 Glodwick, a predominantly South-Asian district, had been a central flashpoint during the 2001 race riots.47 The group was confronted by a gang of South-Asian youths, who attacked Gavin with wooden staves.48 He sustained catastrophic head injuries and died in hospital six days later without regaining consciousness.49

Initially, seven South-Asian men were arrested and faced murder charges.50 However, the case against them systematically collapsed. By 2003, murder and manslaughter charges were dropped against several defendants due to a perceived “lack of evidence”.51 Some were convicted of lesser offences like affray, but the case was effectively closed without anyone being held responsible for the actual killing of Gavin Hopley.52

The failure to secure a murder conviction in a case involving a fatal gang assault in a densely populated urban area dealt a serious blow to public confidence. For critics on the right, the Hopley case came to symbolise a broader institutional reluctance on the part of police and the Crown Prosecution Service to pursue forceful prosecutions in sensitive districts, where concerns about inflaming communal tensions appeared to outweigh the imperative of justice.

Conclusion

Taken together, the murders of Kriss Donald, Ross Parker, Richard Everitt, and Gavin Hopley do not represent a random cluster of tragedies. They form a pattern, not just of violence, but of incompatibility. In each case, the victims were selected not for what they had done, but for what they were: white. And in each case, the cost of that hesitation was borne by ordinary British families.

Multiculturalism has demanded that Britain treat all cultures and peoples as interchangeable, even when some prove openly hostile to the norms that make social trust possible. Where that fiction is maintained at any cost, the cost is paid by the innocent.

If a nation cannot acknowledge that some populations are incompatible, it will continue to manage decline instead of preventing it. Remigration should no longer be treated as unspeakable, but as necessary. The alternative is a country that remembers its dead only when it is safe to do so, and forgets them the moment the truth becomes politically dangerous.