The UK’s Rape Gang Inquiry

Transparency, Testimony, and the Reckoning Westminster Tried to Avoid.

The commencement of the independent Rape Gang Inquiry in February 2026, spearheaded by Independent MP Rupert Lowe, represents a definitive rupture in the British political and social contract. For decades, the systematic rape of young, predominantly White working-class girls by organised Pakistani gangs was grotesquely treated by the state as either a localised failure or a series of unfortunate administrative oversights. However, the testimony emerging from the first two weeks of the Lowe inquiry reveals a far darker and more corrosive truth: a multi-layered, institutionalised betrayal of vulnerable British citizens, driven by an entrenched ideological obsession with racial sensitivities and a catastrophic collapse of moral courage within the political class.1 What is being uncovered is not only incompetence, but a governing establishment so paralysed by the dogmas of multicultural and multiethnic orthodoxy that it abandoned its most basic duty, the protection of its own people. That this inquiry was crowdfunded by ordinary Britons rather than initiated by the state only underscores the depth of the rot. The horrors now being exposed do not simply implicate individual failures; they call into question the very foundations of the United Kingdom’s internal security, legal integrity, and national cohesion.

The proceedings have shed light on the brutal mechanics of what survivors describe as a “conveyor belt” of abuse, where the intersection of illegal immigration and police indifference created a permissive environment for mass rape.2 The evidence suggests that the “grooming gang” phenomenon is not merely a criminal issue but a systemic one, involving the active or passive complicity of social services, local councils, and senior police leadership who prioritised “community relations” over the physical safety of children.3 As the inquiry progresses, the demand for accountability has shifted from the perpetrators themselves to the public officials who facilitated their crimes through deliberate concealment and the systematic silencing of whistleblowers.4

The Lowe Inquiry:

The necessity of a privately funded inquiry into group-based child sexual exploitation highlights the inadequacy of existing state mechanisms. Rupert Lowe launched the Rape Gang Inquiry after concluding that official government reviews were insufficient, delayed, and prone to political sanitisation.5 By February 2026, the inquiry had garnered significant cross-party interest, though it remained functionally independent of the government’s own efforts, which survivors claimed were being “watered down” by expanding the remit to include all forms of child abuse, thereby obscuring the specific racial and religious dimensions of the grooming gang phenomenon.6

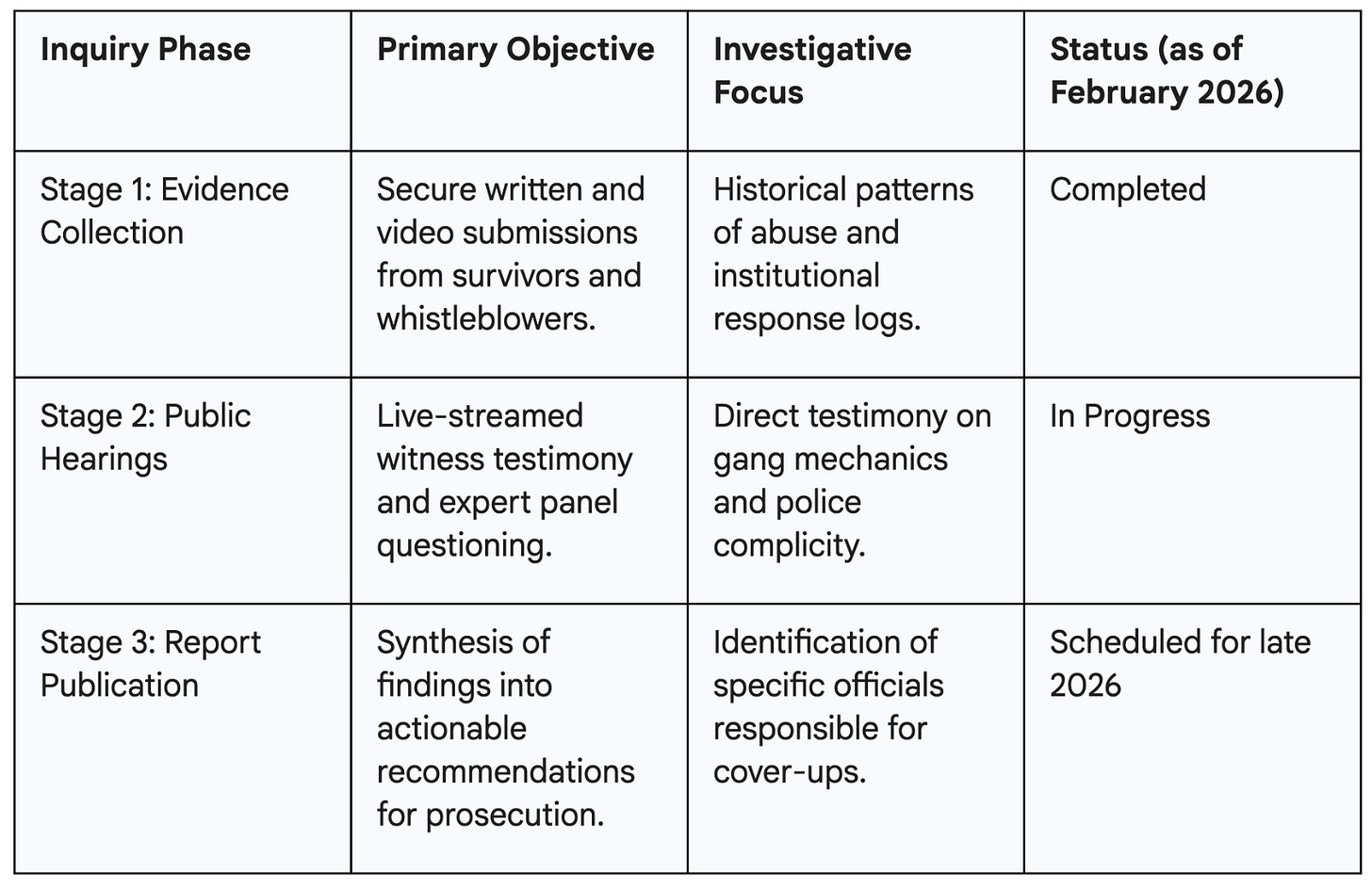

The structure of the Lowe inquiry is designed to bypass the bureaucratic inertia that characterised previous investigations. Funded through public donations, the inquiry operates on a three-stage model: evidence collection, public hearings, and the final publication of findings.7 The transparency of this model, including the live-streaming of hearings, serves as a direct rebuke to the perceived “closed-door” culture of the Home Office and local authorities.

The inquiry specifically targets three fundamental questions: what happened, how it happened, and why it was allowed to persist. This focus on the “why” is particularly pointed, as it necessitates an examination of the ideological and political motivations behind the institutional cover-up. The use of a legal advisory team and a qualified panel ensures that the findings carry weight, even if the inquiry lacks the statutory power to compel attendance, a limitation the panel compensates for by reading questions into the record for those who refuse to appear, effectively using public transparency as a tool for accountability.8

The Bradford Testament: Fiona Goddard and the “Conveyor Belt” of Abuse

The most harrowing aspect of the February 2026 hearings is the sheer scale and depravity of the abuse described by survivors. The testimony of Fiona Goddard, who waived her right to anonymity, provides a granular look at how these gangs operated within Bradford, often under the very noses of the authorities.9 Her account describes a highly organised system where girls in the care of the state were targeted by second-generation Pakistani men.10

Goddard’s experience between the ages of 13 and 18 involved being raped by between 50 and 100 men, only two of whom were not Pakistani Muslims.11 This statistical density points toward a highly specific demographic profile of perpetrators that authorities allegedly sought to ignore. She detailed the existence of “party houses” where at any one time there would be 10 to 20 men constantly coming and going, creating an environment of continuous sexual violence.12 The logistical sophistication of these gangs was described as a “conveyor belt,” where girls were trafficked between cities such as Bradford, Birmingham, and London, transported to various properties to meet “carloads” of men.13

The Integration of Religious and Cultural Observances

A particularly disturbing element of Goddard’s testimony concerns the intersection of the rape gangs with religious observance and illegal immigration. She recounted being told to recruit friends for the “party house” because relatives were arriving from Birmingham to celebrate the Islamic festival of Eid and “expected girls to be waiting here for them”.14 This suggests that the exploitation was not only organised but integrated into wider social and familial networks, with victims treated as commodities for communal celebration. The implication is a level of cultural entitlement and communal involvement that contradicts the “lone actor” narrative.

Furthermore, Goddard testified that the gangs would “bring in more recent arrivals and illegal immigrants” to participate in the abuse. She emphasised that none of these men were “fleeing war” but were instead motivated by the prospect of consequence-free violence against White girls.15 This testimony directly links the grooming gang phenomenon to the failures of the UK’s immigration and asylum systems, suggesting that porous borders and a lack of internal monitoring facilitated the expansion of rape networks.

The Manchester Betrayal: Marlon and Scarlett West

The case of Scarlett West, as testified by her father Marlon West, further illustrates the geographic reach and the systemic nature of the gangs. Scarlett was groomed at the age of 14 in Greater Manchester, following a gang attack at a bus station.16 Her father’s evidence highlights a “county lines” style of human trafficking, where Scarlett was moved between multiple cities, including Bradford and Rochdale, while her family desperately sought help from law enforcement.17

Marlon West’s account is a damning indictment of the Greater Manchester Police (GMP) and social services. He described a scenario where his daughter was raped by more than 60 Pakistani men over a four-year period, yet the authorities dismissed the situation as a “lifestyle choice”.18 This characterisation of a child being raped by dozens of men as a “choice” is perhaps the most egregious example of victim-blaming. Even when Marlon tracked his daughter to a property in Derbyshire, police refused to intervene, claiming she was “safe” with her “friends” who were in fact her groomers some more than double her age.

The Criminalisation of Parents and Victims

The inquiry heard evidence of what can only be described as the criminalisation of the victim and their protectors. Marlon West was told to stop reporting his daughter missing because he was “screwing up the missing persons figures,” a statement that reveals a culture prioritising data management over the life of a child. Furthermore, Scarlett was inappropriately arrested during a police raid on a property where she was being held, and she was later unlawfully strip-searched in custody without an appropriate adult present.19

This pattern of behaviour from the GMP left Scarlett “deeply humiliated” and terrified of the very people tasked with her protection.20 The inquiry heard that she now fears “consequences” for participating in the review, illustrating the total collapse of trust between the state and the victims of group-based exploitation.21 The psychological toll on the family was absolute; Marlon West remarked that the abuse “completely destroyed” his daughter’s personality, and she now “never wants children” to be brought into such a world.22

The Role of the Care System as a Procurement Network

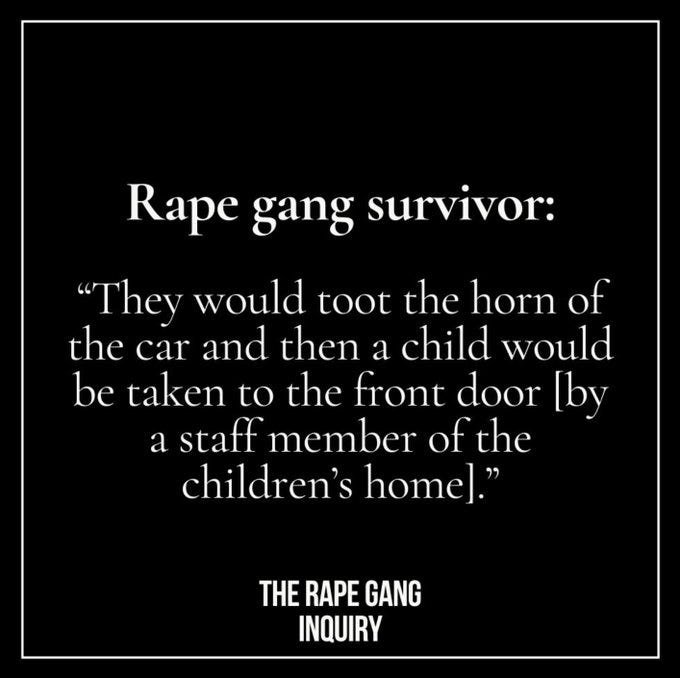

A recurring theme throughout the inquiry is the role of children’s homes and social services in facilitating the grooming process. Testimony and visual evidence presented to the inquiry suggest that some care home staff were actively involved in handing children over to groomers.

Fiona Goddard recounted an incident where police officers allegedly encouraged her to sign herself out of care so that the gang could traffic her to Kashmir to meet their families.23 Only her lack of a passport prevented this overseas trafficking from occurring. This level of complicity suggests that the state viewed vulnerable children as “trouble” to be managed or disposed of, rather than citizens to be protected.

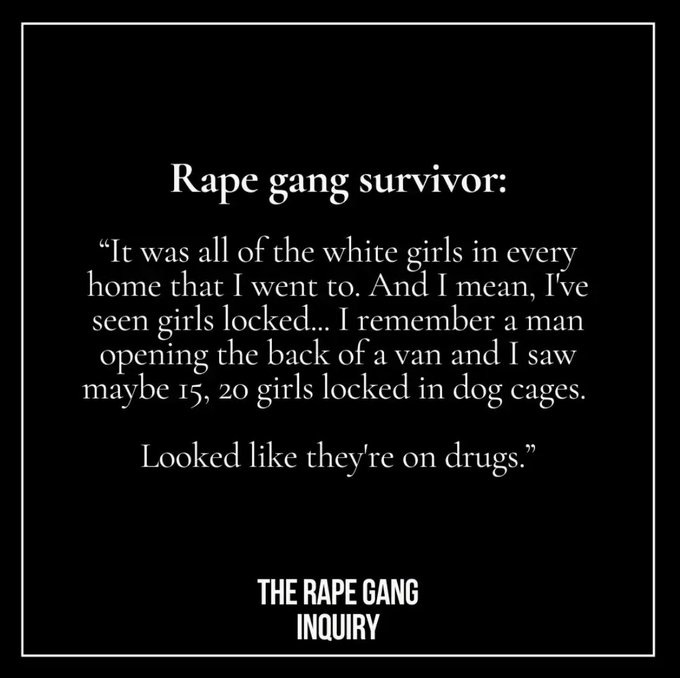

The inquiry also viewed evidence suggesting that victims were held in horrific conditions. One survivor testified to seeing “15, 20 girls locked in dog cages” in the back of a van, appearing to be heavily drugged. This evidence of dehumanisation, treating white children as livestock underscores the predatory nature of the Pakistani gangs and the absolute failure of the state to monitor the movement of vulnerable persons within its borders.

Negligence and the “Racism” Shield

Rupert Lowe articulated the core grievance of the survivors during the hearings, stating that the mass rape of White girls was allowed to “fester away for decades” because officials did not want to be called racist. This “racism” shield functioned as an effective gag on both police and social workers, creating a hierarchy of values where community relations were placed above the physical and sexual integrity of children.24

The inquiry heard from the sister of a survivor who claimed that police “turned a blind eye” due to “racial tensions” and effectively “helped the perpetrators” by ignoring reports.25 This inaction was not only passive but often involved active hostility toward the victims. Fiona Goddard described an encounter with a police riot van where, after being beaten for a full night and attempting to defend herself, she was arrested for possession of a knife while her abuser was allowed to drive away.26

The interaction between Goddard and the three officers in that van serves as a microcosm of the institutional failure. Two older officers laughed and joked while Goddard sat “black and blue” with a ripped top, while a younger officer remained silent, seemingly outvoted or intimidated by the culture of his seniors. This anecdote points to a deep-seated cultural rot within law enforcement, where the suffering of White working-class girls was viewed with derision or indifference.27

The February 2026 inquiry also highlighted the ongoing friction between survivors and the government’s own National Inquiry. Fiona Goddard resigned from the government’s survivor panel, citing “condescending and controlling language” and a fear that the government was attempting to “water down” the investigation.28 The row centered on the government’s preference for the term “group-based child sexual exploitation” (CSEA) over the more specific and descriptive “grooming gangs”.29

Survivors argued that by including all types of abuse, family-based, individual, and stranger-rape, the government was deliberately obscuring the specific sociological and ethnic characteristics of the grooming gangs that had targeted them. This linguistic obfuscation is viewed by survivors as the final stage of the cover-up, where the state seeks to dilute its specific failures into a generalised “societal problem”.30

The Scope of the Crisis: From Rotherham to Bradford

While Rotherham became the initial focal point of the grooming gang scandal, the 2026 inquiry suggests that Bradford may be the site of even more extensive exploitation. Conservative MP Robbie Moore has suggested that the scale of the issue in Bradford will “dwarf” that of previous scandals, with some claims suggesting the number of victims could reach into the tens of thousands.31

The history of Bradford’s failure is particularly long and well-documented by activists, if not by the state. Concerns were raised as early as 2002 by then-MP Ann Cryer, who was approached by mothers reporting that their daughters were being drugged, raped, and systematically exploited. When these concerns were brought to the authorities, Bradford Council reportedly “wanted to ignore it” and “pretend that it wasn’t happening,” dismissing the reports as a “myth”.32 The 2026 hearings confirm that this “myth” was a daily reality for a generation of girls, many of whom were “passed around for sex” while agencies buried their heads in the sand.

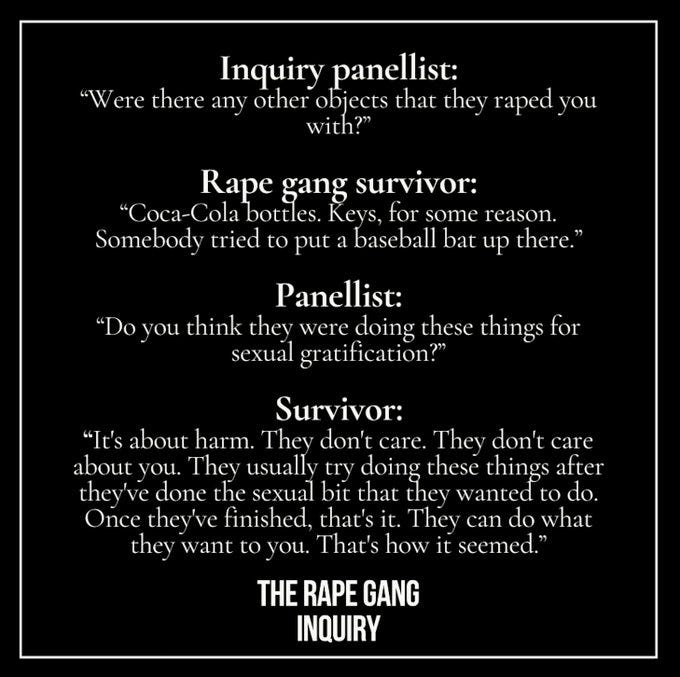

Testimony presented to the inquiry panel also clarified the motivation behind the abuse. When asked if the perpetrators were acting for “sexual gratification,” one survivor responded that “it’s about harm.” The use of objects such as Coca-Cola bottles, keys, and baseball bats during rapes indicates that the violence was intended to humiliate and physically break the victims, rather than being an expression of sexual desire. This distinction is crucial for understanding the gangs not just as criminals but as groups engaged in a form of targeted, demographic-based violence.

Conclusion

What the Lowe Inquiry has revealed is not only tragedy, it is treachery. The testimony emerging from it does not point to isolated mistakes or bureaucratic oversight, but to a systemic failure of duty, courage, and moral responsibility. Institutions that existed to protect the vulnerable instead protected themselves.

With Rupert Lowe now launching his political party, Restore Britain, there may finally be a serious attempt to confront what so many believe the political class has refused to face. For years, public anger has simmered while official inquiries stalled, reports were diluted, and accountability evaporated. If this moment is to mean anything, it must mark a turning point, not just in rhetoric, but in action.

As Lowe himself has said, “we will protect women and girls, if millions must go, millions will go.” The safety of women and girls can no longer be subordinated to political caution or institutional self-preservation.

I am confident he will do well. There is an unmistakable undercurrent across the country, a growing conviction that the public will no longer accept anything less than a safe and recognisably British Britain.