Afrikaners Face an Uncertain Future

Note: In December 2011, I visited South Africa for two weeks to compose a journalistic piece on the state of the Afrikaner people since the end of Apartheid in 1994. That article eventually ran in a journal which is now out of print. But with Afrikaners in the news again these days, I thought it would be appropriate to republish portions of this article, in order to provide context for the complex historical situation facing the “white tribe” today.

I have business in Gauteng before I return to the States, so I leave Orania behind on an early Sunday morning while everyone’s at church, winding my way back to suburban Jo’burg. I opt, however, to spend an evening in the city of Bloemfontein to see the Women’s Monument, a site first christened in 1913, dedicated to the remembrance of the women and children who were rounded up by the British during the Anglo-Boer War and dispatched to concentration camps, where many thousands starved to death.

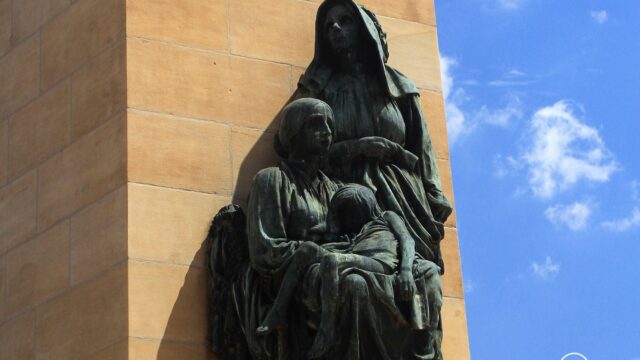

The main fixture of the site is heart-grabbingly powerful (see above). Before a massive obelisk, on a platform ten feet above the ground, there are three sculpted figures: a young woman bears a dead child in her arms, a desperately forlorn look upon her face; she is flanked by a middle-aged woman, who gazes into the distance stoically.

As I stand at the foot of this statue, I find myself tearing up a bit; the simultaneous torment and determined endurance on the faces of the two stone women somehow says everything one needs to know about the horrors of “total” war and its dreadful victimization of the innocent. During the Anglo-Boer war, the British resorted to horrifying atrocities in order to achieve domination over the scrappy Afrikaners; they slaughtered livestock, burned down farms, and doomed helpless civilians to sure, agonizing deaths. They weren’t the first ones to do such things—Generals Sherman and Sheridan, under the command of Abraham Lincoln, decimated the American South in much the same manner half a century before. Nor was the British army the last to go “scorched earth” on its enemies, as all familiar with the bitter history of 20th-century warfare, and the hardly less horrifying first decade of the 21st century, can attest.

But one cannot escape the sense that the British establishment of concentration camps represents some massively significant betrayal of ostensibly humane and “civilized” Western values, regardless of which side, the Brits or the Boers, had the more legitimate claim to political control over the Orange State and the Transvaal back in 1899. The Afrikaners suffered horrendously in this war, in manifold ways: physically, psychologically, and spiritually. Anger and bitterness for the wounds they endured at the hands of the British, in fact, still fester viciously to this day, over a century later.

***********************************

Three days after viewing the Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein, I visit another important Afrikaner landmark, and I once again find myself emotionally shaken, moved beyond measure for reasons I barely understand. The Voortrekker Monument sits atop a hill in the outskirts of Pretoria.

It is an imposing, cathedral-like edifice— somewhere near 130 feet tall—which can be viewed from a vast distance. In some ways, the Voortrekker Monument is the architectural antithesis of the Women’s Monument. Completed and christened in 1949, it celebrates a major victory for ascendant Afrikanerdom just as the Women’s Monument commemorates the horror and humiliation of an ignominious defeat.

The year before the construction of the monument, in 1948, the Afrikaner-favored National Party, led by D.F. Malan, defeated Jan Smuts, long-standing incumbent prime minister of the British-led United Party. A half century after losing the Anglo-Boer War, the Afrikaner had at last seized the upper hand and taken control.

Afrikaners tend to view Malan’s electoral triumph of 1948 the same way that most of today’s Black population sees Mandela’s ascension to the South African presidency in 1994: it was a moment, following a great, decades-long struggle, in which they finally won what they felt to be their birthright. Crucial in building this victory was a canny campaign to celebrate the heroic valor of the Boer Voortrekkers of the previous century, who under the leadership of Andries Pretorius, won what they felt to be a miraculous victory over far-superior Zulu forces at Blood River in present day Kwazulu-Natal on December 16, 1838.

Prior to the battle, the Voortrekkers had suffered several terrible defeats on the veldt at the hands of Dingaan Zulu’s mighty army, including a notorious “sucker-punch” ambush in which Dingaan invited Piet Retief and various other Voortrekkers to his camp under the auspices of signing a peace treaty, before directing his troops to torture and massacre the unarmed White men. Following this grievous incident, Zulu warriors conducted numerous destructive attacks on Voortrekker laagers, killing around 500 men, women and children.

Reeling with grief, and facing the prospect of impending utter extinction, the bedraggled camp of devoutly Christian pioneers led by Pretorius turned to prayer. On December 9, they took a vow, declaring before heaven that if God granted them victory in the coming battle, they would forever commemorate the date. A week later, on December 16, the ragtag 480 Afrikaners turned away a fiercely invading force of Zulu impis numbering somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000, killing over 3,000 of their enemy and suffering not a single casualty in the process. It was afterwards hailed as Geloftedag, or “Day of the Vow.”

Geloftedag is still a holy day in the traditional Afrikaner calendar, a day to remember the bravery and dedication of one’s ancestors, as well as being a time to give thanks to the Almighty for his manifold blessings. It is like Thanksgiving, Veteran’s Day, Passover, and the Fourth of July all rolled into one: a time for unabashedly celebrating one’s national and ethnic heritage, while also engaging in solemn, sober spiritual reflection.

Geloftedag services are held in churches, parks, and other locations across the country, but the Voortrekker Monument is the largest and most publicized of all such venues. The building itself is an extraordinary enough place to investigate even on a quiet day. One ascends its massive staircase and walks along the length of its impressive exterior, scrutinizes its high stone walls flanked by massive statues of bearded Boers holding huge rifles, and one is filled with a sense of awe, as well as a kind of terror.

This is a structure designed to intimidate; there is an undeniably brutal quality to its beauty. If the Voortrekker Monument had a voice, it would be low, loud, and thunderously threatening. It is the sort of building that Leni Reifenstahl would have loved to use as a set piece. To call it an example of “Fascist architecture” may be misleading, since ideological affinities between National Party-led South Africa and Nazi Germany are quite tenuous, for reasons already mentioned. Still, just as the National Socialists in Germany chanted “Seig Hiel” at their rallies, the Voortrekker Monument unashamedly demands that we “hail” a glorious “victory” for the Afrikaner tribe in South Africa.

*****************************************************************

If one objects that everything seems crudely simplistic and shamelessly triumphalist in tone, it could reasonably be retorted that all sites dedicated to national accomplishments and ideals—from Mount Rushmore to Trafalgar Square to the Arc de Triomphe—share this characteristically unselfconscious “hurray for our side” spirit of chauvinistic bravado.

Today, of course, in our politically correct “post-colonial” age, historically White nations are discouraged from indulging in such sentiments, thus lending the Voortrekker Monument a rather delicious air of ripe, forbidden fruit. The majestic interior contains a marble frieze which runs across the wall from one side to the other—a pictorial history is presented of the Voortrekker movement. We see the Boers leave the Cape and escape British tyranny to forge a destiny for themselves in the wilds of a savage and untamed continent. We see Piet Retief’s disastrous—and fatal—mistake of attempting to make peace with the double-dealing Dingaan. We witness Zulu impis preparing to kill Afrikaner women and children; the Black warriors brandish their spears before helpless throngs of terrified Whites. One old woman holds a baby in the crook of her left arm while she reaches out with her right hand and grasps the muscular arm of a Zulu; she looks up at him beseechingly, but he glowers back at her with pitiless hatred. A boy tries to shield his younger sister from attack by putting his little arms over her head; another boy picks up a musket dropped by his dead father, and takes aim at his attackers, thus presaging the ultimate triumph of frontier gumption and divine will in the miraculous victory of Blood River.

The final scene in the frieze is, indeed, a depiction of this famous battle, in which the embattled Boers routed an army 20 times their size. For a people that now view themselves as outnumbered and existentially imperiled, every day losing ground to their enemies, the contemplation of such an incredible past triumph must inspire the same sort of pride and reverential longing that an observant Jew must feel when he ponders the notion of the Red Sea parting at Yahweh’s command, saving the Israelites from certain doom.

On Friday, December 16, 2011, I attend Geloftedag ceremonies at the Voortrekker Monument. It is a bright, brilliant day, and by 8 a.m., a large crowd has already gathered. Once more, as at Orania, I am struck by just how un-striking the

gathered throng appears. Most are dressed in semi-formal attire, as one would for church, but many more wear jeans, shorts, and sneakers. Very few sport 19th-century period costumes, which is a bit of a disappointment. . . I’d expected to run across some colorful, brash, outspoken, feisty characters, but for the most part, this crowd just seems like a lot of orderly, peaceable, well-behaved White folks. I would almost call them innocuous. Aside from the penchant of many children to go barefoot (a unique Afrikaner cultural phenomenon) and the prevalence of the Afrikaans language, these people could be amiable, mild-mannered suburbanites sitting beside me at an Atlanta Braves game at Turner Field.

Still, the fact that so many of them went out of their way to attend this event must be significant, and it’s quite possible that I, an uitlander who doesn’t speak the language, am missing something. The people pack into both levels of the building, while some find shady places to sit outside; led by a keyboard player and a cantor, the crowd duly sings patriotic songs and Christmas carols from a shared program. A smiling minister delivers a sermon in a friendly, personable manner—an Afrikaner friend later tells me that he emphasized the importance of acting for the glory of God, not out of a desire for personal gain. Though this pastor related his message to the Blood River battle and its aftermath, the content of the homily still sounds like standard evangelical boilerplate, like something one might hear delivered by some blandly handsome young preacher at a Baptist megachurch in heartland America. It somehow seems like a “lite” version of Afrikanerdom, a watering down of the fierce, uncompromising spirit which built this edifice over half a century ago.

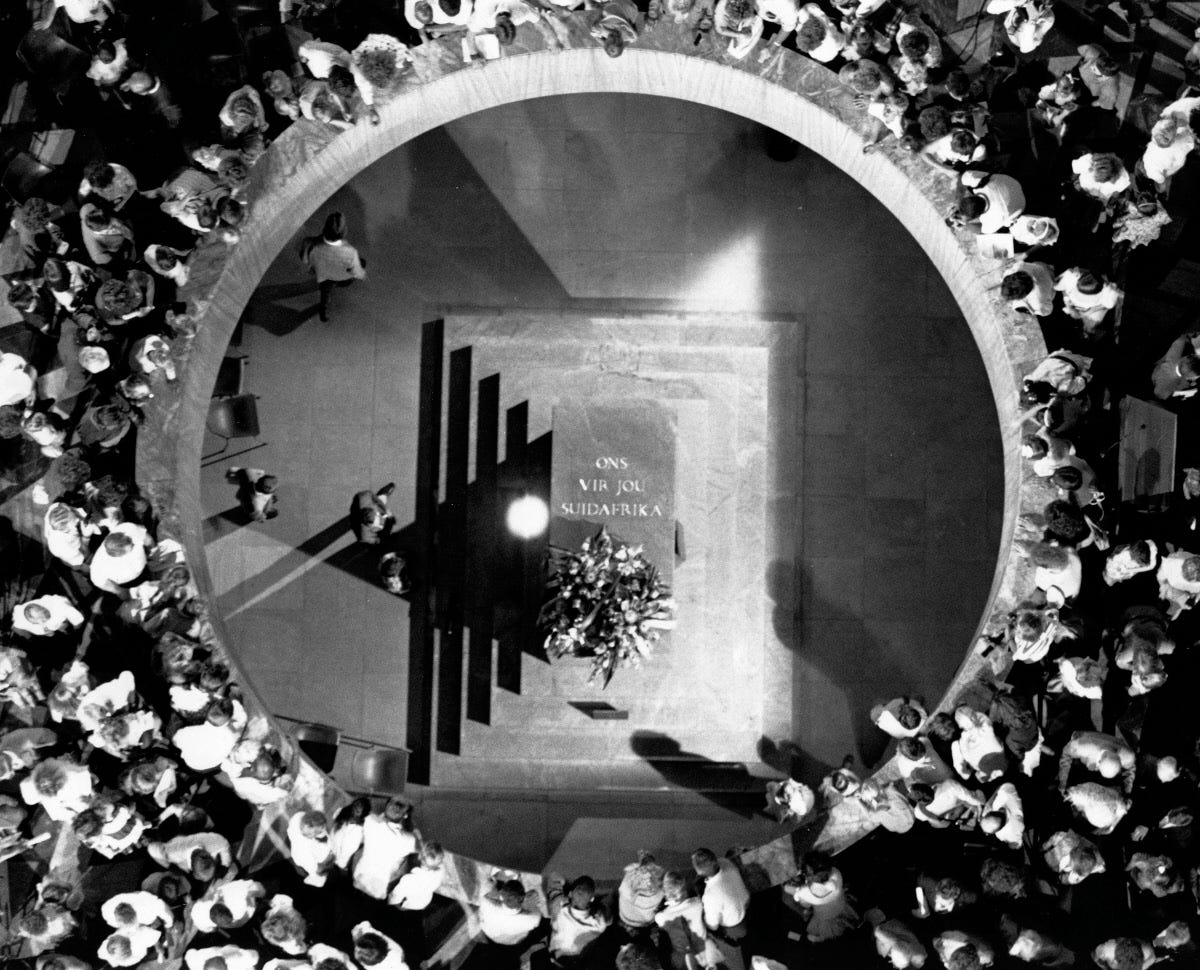

But just as I began to fret that the Boer cause may have been rendered utterly toothless by modernity, I found myself witness to a moment of real, almost elemental power, which convinced me otherwise. Of course, this moment has to wait until all of the singing, and the speechifying, has ceased. Afterwards, the crowd gathers around a cenotaph, or plaque, located in the middle of the bottom floor. Some lean over the railing of the floor above, and peered downward. On the cenotaph reads the words “Ons vir jou, Suid-Afrika” (“We for you, South Africa”).

As the noontime hour approaches, a beam of sunlight shines through a strategically carved hole high above our heads in the roof of the Monument; the crowd buzzes excitedly as the circle of sunshine makes its way along the floor, before finally alighting on the cenotaph at exactly 12:00. Then the crowd suddenly stands, and in lusty, full-throated voices, belts out “Die Stem van Suid-Afrika,” the former national anthem of South Africa prior to 1994:

From the blue of our heaven

From the depths of our sea,

Over our eternal mountain ranges

Where our cliffs their answer give

We will answer to your calling,

We will offer what you ask

We will live, we will die, We for Thee, South Africa!

Following this impromptu performance, the crowd gives a hearty cheer, then several parents send their children to pose in front of the sunbeam as they take photographs. People are still standing in a circle, facing one another, and I feel myself in some ways witness to a nation facing itself, wondering what comes next.

It is grand and glorious to sing together, as if with one voice, of giving one’s life for one’s country, but what does one do when the song ends, and one recalls that his country, in essence, no longer exists?

It is a dire question that many in Europe and North America will no doubt be asking themselves in the coming years. Due to his immediate circumstances, the Afrikaner feels urgently compelled to ask it now. Whether he ultimately succeeds or fails to find the correct answer, we will find much to learn from observing the various steps he is currently taking to attempt to secure a proper homeland for himself and his children.

And if he actually manages to triumph, against all odds, and again emerges victorious, as his ancestors did at Blood River, then unreconstructed Westerners will find in the study of the Afrikaner’s present struggles an invaluable treasure, an ace that we can keep in the turbulent times ahead.

https://andynowicki.substack.com/p/afrikaners-face-an-uncertain-future