Why Are We Christians?

A commenter wrote under my article “The Satanic False Flag” that I am missing the point that “Christianity spread through voluntary adoption,” and that “the willing adoption of Christianity by so many disparate people indicates what’s analogous to a superior technology, where Christianity clearly was a much better understanding of the transcendent compared to other faiths.” In conclusion, he added, “rejection of Christ is folly and has no bearing on bettering the situation the West finds itself in.”

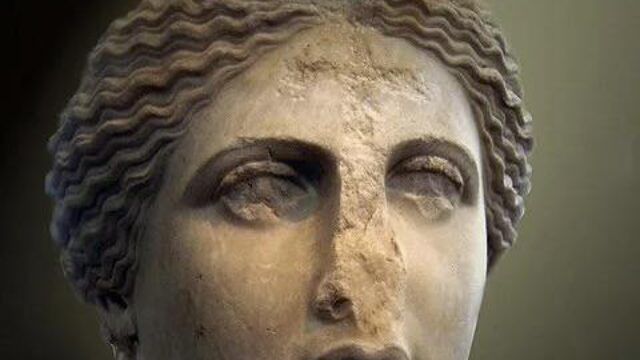

Here is my response. The question whether Christianity is vital for Western civilization, I have answered in “The Renaissance Genius”: the greatness of Western civilization, in science, in art, in philosophy, in politics, in ethics, stems primarily from its Helleno-Roman roots. The Greek miracle, not the Christian revelation, is vital to the West. Next, is the Christian “understanding of the transcendent” superior to other faiths? I think not, and I have explained why in “How Jewish is the Christian God?”: the maniacal, anthropomorphic God of the Bible is a headshrinker, compared to the Cosmic God of the Stoics.

Beyond this, my fundamental premise is that it is necessary, not just for the betterment, but for the survival for the West, to get to the bottom of the Jewish question, and the bottom of it is the fake Jewish god (the god of the Jews who claimed to be God who claimed to have chosen the Jews to rule the world). Therefore, we cannot get around a critic of Christianity. The Christian question is the flip side of the Jewish question, which has now become the Israeli question. It is the question of Christendom’s responsibility—and complicity—in Jewish Power. I know that most Christians reject the Jews’ claim to be metaphysically superior, but they are inconsistent: how can Jesus be the Messiah if the Jews were not God’s chosen? Jews and Christians do not agree on the Messiah, but they agree that the Jews are the only ethnic group ever chosen by God, with a divine command to genocide their enemies, whose gods were devils in disguise. And for every E. Michael Jones, there are dozens of Ted Cruz saying “the Bible tells me to support Israel.” That is a very stupid thing to say, but it is a very Christian thing: only Christians and Jews can view supporting Israel as a religious command. Only Christians and Jews view Jerusalem as the center of the world.

I take no pleasure in hurting people’s religious feelings; I’m writing only for those of you who want to get to the bottom of the Jewish question. But I do insist that a critic of Christianity doesn’t mean the “rejection of Christ”. It can mean the liberation of Christ. Let’s not confuse Christ and Christianity. The life and philosophy of Jesus are deeply inspiring; I’m not questioning that. Actually, my subject here is not even Christianity as such: it is the process by which Nicaean Christianity became the compulsory and exclusive religion of all Europeans, and the long-term consequences of that process. My subject is not so much Christianity as Christianity’s war and victory over all other forms of worship and belief—a war and a victory so total that most Christians hardly know anything about the heaps of ruins on which they are standing.

We call these ruins “paganism”, but what are we talking about? A Christian construct: “the thing so arrogantly called paganism [was] in fact all the many hundreds of the Empire’s religions save one,” as Ramsay MacMullen put it.[1] Alan Cameron concurs:

There is a very real sense in which Christianity actually created paganism. … The lumping together of all non-Christian cults (Judaism excepted) under one label is not just an illustration of Christian intolerance. As far as the now Christian authorities were concerned, whether at the local, church, or governmental level, those who refused to acknowledge the one true god, whatever the differences between them, were for all practical purposes indistinguishable. … Fourth-century pagans naturally never referred to themselves as pagans, less because the term was insulting than because the category had no meaning for them.[2]

To say that Christianity won because of some inherent superiority is a Darwinian-type tautology. How do we know that Christianity was superior, apart from the fact that it won? Perhaps it won because emperors deemed it the best suited for the social engineering they had in mind. Perhaps Christianity won simply because it was the most intolerant religion, and therefore the most lethal to its competitors. Does the fact that Elijah and Jehu eradicated Baalism by slaughtering all the priests of Baal (1Kings 18 and 2Kings 10) prove the superiority of Yahwism over Baalism? Only in a Darwinian sense.

There is even the possibility (which I have explored in “How Yahweh Conquered Rome”) that Christianity won because it was sold to the Romans by the greatest religious peddlers, the Jews, as their god’s Trojan Horse into the Gentile city. If so, Christianity won not because it was the best for us, but because it was the worst.

If Christianity had been so obviously better for the Romans, then let’s reverse the question: why did the Romans resist it so hard? Despite the Edict of Thessalonica issued by Theodosius I in 380, outlawing all religions except Nicaean Christianity (and Judaism), his grandson Theodosius II lamented 58 years later—one century after Constantine’s death—that so many still resisted baptism, unconvinced that this spiritual vaccine was for their good: “A thousand terrors of the laws that have been promulgated, the penalty of exile that has been threatened, do not restrain them!”[3] The Christianization of urban Roman populations was not completed before Justinian (527-565), and with tremendous violence. Peasants resisted much longer, and converted on their own “pagan” terms.

The story of the peaceful Christianization of the Roman Empire has been brought to us by ecclesiastical historians, starting with Eusebius of Caesarea, who, by his own admission, wrote only what he deemed “useful” (you will not learn from him that his hero Constantine murdered his father-in-law, his wife and his son).[4] Because few non-Christian primary sources of that period have survived Christian censorship, historians have tended to repeat what really amounts to Christian apologetics—or propaganda. In fact, until the nineteenth century, secular historians preferred to leave the topic of Christianization to specialists of “Church history”, who were, with few exceptions, theologians formed in seminaries. A critical history of the Christianization began in the late nineteenth century (the French Ernest Renan comes to mind),[5] but only since the second half of the twentieth century have “revisionist” historians given us a broadly objective picture (see the bibliography at the end).

Christianization as depaganization

Richard Fletcher writes in The Conversion of Europe:

Constantine did not make Christianity the official religion of the Roman empire, though this is often said of him. What he did was to make the Christian church the most-favoured recipient of the near-limitless resources of imperial favour. An enormous new church of St Peter was built in Rome, modelled on the basilican form used for imperial throne halls such as the one which survives at Trier. The see of Rome received extensive landed endowments and one of the imperial residences, the Lateran Palace, to house its bishop and his staff. Constantinople, begun in 325, was to be an emphatically and exclusively Christian city–even though it was embellished with pagan statuary pillaged from temples throughout the eastern provinces. Jerusalem was provided with a splendid church of the Holy Sepulchre. Legal privileges and immunities rained down upon the Christian church and its clergy. The emperor took an active part in ecclesiastical affairs, summoning and attending church councils, participating in theological debate, attempting to sort out quarrels and controversies.[6]

Such imperial heavy-handed promotion of Christianity was one side of the story. The other side was the just as heavy-handed discrimination of all other religions (“paganism”). The building and adornment of lavish churches, as well as Constantine’s abundant gold coinage (the solidus), were done at the expense of pagan temples, which were deprived of public funds, expropriated, or destroyed. Diana Bowder writes in The Age of Constantine and Julian:

in 331 a treasury depleted by the works at Constantinople and by his own extravagant generosity led Constantine to order the making of a general inventory of the goods, and probably revenues, of the pagan temples; and this was made the occasion for stripping them of their gold and silver and of such things as bronze doors and roof-tiles. Earlier emperors, pagans, had laid their hands on temple treasures in their hour of need, but this time there was an intentional element of derision, as gold plating was removed from cult images, and the core and stuffing materials exposed to public scorn. Land belonging to temples was also confiscated, and the more important sanctuaries consequently lost much of their means of support. Many of the statues—including cult statues—taken to decorate Constantinople were probably also plundered at this time. Several major temples were actually closed down…[7]

The looting of temples intensified under Constantine’s sons, with the encouragement of bishops and bigots such as Firmicus Maternus: “Take away, yes, calmly take away, Most Holy Emperors, the adornments of the temples. Let the fire of the mint or the blaze of the smelters melt them down, and confiscate all the votive offerings to your own use and ownership” (On the Error of Profane Religions, XI).[8]

That is only for the material aspect of that religious war started by Constantine. That war was inherent to Christianity, regardless of Constantine’s original intent. By the Edict of Milan (313), under the pretext of religious tolerance, Constantine brought religious intolerance into the Roman Empire, by legalizing the most intolerant religion. He did not declare other cults illegal, but ten years later, his open “declaration of tolerance” already sounded less tolerant: “Let those, therefore, who are still blinded by error, be made welcome to the same degree of peace and tranquility which they have who believe.”[9] Things could only get worse. Ecclesiastical historian Sozomen wrote (Ecclesiastical History, II, 5):

It appeared necessary to the emperor [Constantine] to teach the governors to suppress their superstitious rites of worship. He thought that this would be easily accomplished if he could get them to despise their temples and the images contained therein. To carry this project into execution he did not require military aid; for Christian men belonging to the palace went from city to city bearing imperial letters. The people were induced to remain passive from the fear that, if they resisted these edicts, they, their children, and their wives, would be exposed to evil.

After Constantine, it became increasingly central in imperial discourse and legislation that non-Christian temples, rites and beliefs were offensive to the true and only (Jewish) God, and were therefore to be treated as a security risk for the Empire. The more Christian the empire became, the more aggressive against “paganism” it had to become—not by nature of the empire, but by nature of Christianity.

Christianity as a conspiracy theory

Christian apologists and missionaries taught that all gods but the biblical Yahweh are demons conspiring to enslave humans and lead them to hell. Christianity had been outlawed by Diocletian precisely because of the Christians’ overt disrespect for the empire’s divine protectors, which threatened the pax deorum as well as civil peace. Christians were called atheists. After Constantine, the policy was reversed.

Until Christ was sent to this world, Christians say, only the Jewish people knew the real God, who had revealed Himself (and his name) to Moses. All other nations were ignorant of God, and the gods they worshipped were actually demons pretending to be gods—not daimones in the Greek sense of “spirits”, but agents of the Devil, Lucifer, the Serpent who had deceived Adam and Eve and lured them away from God. As I pointed out earlier, the great God of the Canaanites earned the honor of becoming the Devil himself, under the name Beelzebul, although there is no record of him ordering genocides, the slaughter of priests, or even the ritual mutilation of newborns.

Christian missionaries denounced the gods of “paganism” as crypto-devils. They did not claim that Christ had destroyed them—for then there would be no more need for Christ—but that baptism and mass would cleanse and protect you from them. The final victory would only come at the endlessly postponed End of Days.

In their conspiracy against humans, fumed the saints, the fallen angels had managed to imitate Christian salvation even before it became available, thanks to their demonic foreknowledge of God’s plan. Such was the theologians’ response to the pagans who accused Christians of plagiarism. For example, similarities between Mithraism and Christianity, both in their myths and sacraments, were due to Mithras’ imitatio diabolica, according to Tertullian of Carthage. Eusebius of Caesarea elaborated that conspiracy theory in his Gospel Problems and Solutions (Quaestio 124, “Adversus Paganos”):

But the devil—I mean Satan—in order to lend some authority to his deceptions and to color his lies with a false appearance of truth, used his power, which is real, to institute pagan mysteries during the first month, in which he knows that the holy ceremonies of the Lord are to be celebrated. In this way, he chained their souls in error, and this for two reasons: first, the lie anticipated the truth; the truth therefore appeared to be a lie, the very anteriority creating a prejudice against it; secondly, because, in the first month in which the Romans observe the equinox as we do, this observance is accompanied for them by a ceremony in which they claim to obtain atonement by blood, as we obtain it by the cross. Thanks to this ruse, therefore, the devil holds the pagans in error; They imagine that the truth, which is ours, is not the truth, but an imitation, forged by some superstition to compete with them. “For it is impossible,” they affirm, “to consider as true an invention that comes after the fact.”[10]

In conclusion, we must understand that it is in the very nature of Christianity to fight to the death against other cults, and as soon as Constantine gave Christianity his support, he set in motion the process that could only lead to the crushing of paganism to the last god. In those days, being a Christian meant being a soldier for Christ, engaged in a war of attrition against the gods. Building the Church meant destroying the temples; there was no more important mission to the Church. “It was this result, destruction, that non-Christians of the time perceived as uniquely Christian,” writes Ramsay MacMullen in Christianizing the Roman Empire; “and it was this result which in turn gave so grave a meaning, from the pagan point of view as well as the Christian, to the successive waves of persecution. They were so many waves of desperation.”[11]

Why desperation? Because under the derogatory term of “paganism”, Christians were in fact attacking not only every other cult, but virtually every social activity.

“Paganism” as the totality of social life

There was not a banquet, a festival, or a social gathering in which the gods were not invited. Temple precincts served as hostels, theaters, marketplaces, hospices for the poor, and medical centers. Every form of art was religious. There were an estimated 30,000 statues of deities in the Roman Empire.[12] MacMullen writes in Paganism in the Roman Empire:

The entire range of musical instruments known to the world of the Apologists was called into the service of the gods in one cult or another, so along with every conceivable style of dance and song, theatrical show, prose hymn, lecture or tractate philosophizing, popularizing, edifying, and so forth—in sum, the whole of culture, so it would seem. The same conclusion can be expressed negatively. From the arts of those centuries, remove everything that was not largely devoted to religion. The heart of culture then is gone.[13]

Even sport competitions were offered to the gods: for that reason, the Olympic games were abolished by Theodosius in 392. Every journey, even for commercial purpose, was an occasion to visit a local shrine, and religious fairs attracted people of all walks of life from tens if not hundreds of miles away. “Whatever their size or area of attraction, they constituted one of the chief means of introducing someone to a larger world than that in which he was likely to pass his workaday life.”[14]

One of the most moving defense of paganism is the letter addressed by pagan rhetorician Libanius to Emperor Theodosius in 386, pleading for the preservation of the temples against the predation of Christian monks, who, he claimed:

hasten to attack the temples with sticks and stones and bars of iron, and in some cases, disdaining these, with hands and feet. Then utter desolation follows, with the stripping of roofs, demolition of walls, the tearing down of statues and the overthrow of altars, and priests must either keep quiet or die. After demolishing one, they scurry to another and to a third, and trophy is piled on trophy. Such outrages occur even in the cities, but they are most common in the countryside.

Libanius looks back with nostalgia to the time when temples were “a sort of common resort for people in need.” They are “the soul of the countryside,” he says;

they mark the beginning of its settlement, and have been passed down through many generations to the men of today. In them the farming communities rest their hopes for husbands, wives, children, for their oxen and the soil they sow and plant. An estate that has suffered so has lost the inspiration of the peasantry together with their hopes, for they believe that their labor will be in vain once they are robbed of the gods who direct their labors to their due end. And if the land no longer enjoys the same care, neither can the yield match what it was before, and, if this be the case, the peasant is the poorer, and the revenue jeopardized. (Oration XXX, “Pro Templis”, 8-10)[15]

In short, comments MacMullen, “the old religion suited most people very well. They loved it, trusted it, found fulfillment in it, and so resisted change however eloquently, or ferociously, pressed upon them.”[16]

It was not really one religion, rather a general consensus of religious tolerance. And for peoples throughout the Roman Empire, there was nothing unique or exceptional in the Christian cult—certainly not the notion of an immortal demi-god—except its fanatic intolerance to all other religions. In resisting Christianization, the so-called “pagans” were not so much fighting against Christianity as they were fighting for their freedom to worship the gods or heroes of their ancestors. What Christianity condemned and ultimately destroyed under the name “paganism” was, in fact, “tradition”: the bond between generations, rootedness, belonging.

The appearance of Christianity meant not only a war of one new religion against all ancestral religions. It was the appearance of something totally new, for which the Romans had built no immune system. Alan Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome: “A large part of the reason paganism yielded comparatively easily and rapidly (at least in the West) is precisely that pagans in different parts of the empire had so little in common”[17]—apart, that is, from religious tolerance. Many assumed, at first, that tolerance of Christianity was a good thing, because they had no experience, not even historical records, of such an aggressively intolerant religion as Christianity proved to be.

Ban on sacrifices and defunding of pagan cults

Besides the arbitrary looting of temples beginning in 331, from which “tremendous wealth in precious metal … flowed into the imperial treasure” (Ramsay MacMullen),[18] two legal measures were particularly damaging to non-Christian religious practices: the ban on animal sacrifices and the defunding of public cults. They started under Constantine’s three sons, but took a more severe turn after the brief “pagan restauration” of his nephew Julian (361-363)—that is, under Valentinian, his brother and his two sons (364-392), followed by his son-in-law Theodosius and his heirs (379-457).

Constantine had forbidden that Christian clergy be “compelled” to “celebrate” sacrifices in public ceremonies. Under his sons, several edicts forbade animal sacrifices entirely.[19] This was to strike at the heart of the Roman way of life. Christians have often condemned animal sacrifices as cruel, primitive and, of course, satanic. But it is important to understand that, in the ancient world, taking an animal’s life was never a purely secular matter. Charles Freeman writes about the Greeks:

The sacrifice was the central point of almost every ritual. An animal, an ox, sheep, goat or pig, would be presented to the gods and then killed, burnt and eaten by the community. Sacrifices were not an aberrant or cruel activity—they were a sophisticated way of dealing with the necessity of killing animals in order to eat. In fact the rituals surrounding sacrifice suggest that the Greeks felt some unease about killing animals they had reared themselves. So the illusion was created that an animal went to its death willingly and before the killing all present threw a handful of barley at it, as if the community as a whole was accepting responsibility for the death.[20]

Needless to say, animal sacrifices were not shows of ascetic spirituality. In Roman times, they were often boastful displays of wealth and prodigality, as the offering of animals brought prestige and popularity. Philosophers found them repellant. But the “idea” of sacrifice was not in itself a mark of cruelty or materialism. It was a basic, universal principle of humanity. Any banquet, any festival, any occasion for a shared carnal meal involved some kind of ritual invocation to the gods, so that banning animal sacrifices was not only perceived as an insult to the gods; it was an assault against everything that made life worth living.

Public religious life included temples, priesthoods, festivals, sacrifices, and the feeding of the poor and less poor. The Roman state used to be its main sponsor. Michael Gaddis: “Emperors as far back as Octavian Augustus had held that their primary duty was to safeguard the pax deorum, the ancient arrangement by which the gods provided peace, security, and prosperity to the human race in return for proper worship and sacrifices.”[21] That is why the emperor was pontifex maximus, overseeing all religious cults. But the Christian god is a jealous one, and his spokesmen insisted that emperors and governors cease paying for and participating in public cults. It took some lobbying time. Alan Cameron: “It was not till Gratian [367-384] and Theodosius [379-395] that Roman pagans were faced, first with the withdrawal of public funds, and then with being forbidden to perform their rituals publicly.”[22] A rescript of Honorius, Theodosius’s son, sent to Carthage in 415, commands that “in accordance with the constitution of the sainted Gratian … all land assigned by the false doctrine of the ancients to their sacred rituals shall be joined to the property of our privy purse,” the decree being valid “for all regions situated in our world.”[23]

To some extent, private contributions could make for the suppression of public funding. The rich had always paid for the building and repair of temples as well as other public work. However, it was understood that public funding and public performance were indispensable for the validity and efficiency of public cults, in Rome as in other cities. The economic and political war against paganism had profound effect, because most Romans thought of the gods’ protection as the source of Roman greatness.

Discrimination and opportunism

The senatorial aristocracy was “of central importance in the Christianization of the empire,” Michele Salzman explains in The Making of a Christian Aristocracy, especially since “[t]he Romans had never separated the secular from the sacred. For centuries the same men who held high state office also held the most important priesthoods in the pagan state cults.” Christianity had little appeal to this class, despite accommodations such as Jerome’s reinterpretation of nobilitas as a Christian virtue. But the old Roman aristocracy, while immensely rich, had lost much of its political power in the late third century, to the equestrians, the upstart provincial nobility, the military, and career bureaucrats.[24] All these people were competing for imperial appointments, and highly suggestible to religious discrimination. “At the very moment when the Constantinian dynasty declared its new religious allegiance,” Peter Heather writes, “the landowning classes of the Empire were queuing up for jobs in a rapidly expanding imperial bureaucracy.” Therefore, “the structures of the imperial system, and, in particular, the precise ways in which they shaped competition between members of the landowning elite, played a critical role in the process [of conversion].”

the vast majority felt that they had no choice but to come into line in some way with the new imperial cult sweeping through the fourth-century Empire. The emperor was willing to tolerate some carefully tempered dissent, but even this much ran the risk that a well-connected converted competitor might use the operations of public life to undermine you. Unless you were willing to oppose outright, as a minority certainly were, then—real, fake, or something in between—an accommodation had to be made. The alacrity with which many converted is a strong indication in itself that, for many, deep religious convictions were not in play.[25]

Significantly, no aristocrat left a story of his conversion in the fourth century—apart from Augustine, who was a Manichean when he converted. Ramsay MacMullen writes in Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100-400):

people were joining the church partly to get rich, or at least less poor. That was a motive assumed by contemporaries. It hardly needed to be explained; nor was it considered anything especially to boast about. Accordingly, explicit testimonies of the sort, “I call myself a Christian because I can’t afford not to,” are quite lacking. But the thought must have been there.[26]

The 360s, under Gratian, were a pivotal time in the discrimination against non-Christians for civic careers, and in 408, the Western emperor Honorius decreed that non-Christians could no longer serve in the imperial administrative bureaucracy.

Even bishoprics became coveted by opportunists, because bishops were “rapidly assimilated as quasi civil servants into the mandarinate which administered the empire.”[27] Pegasios, bishop of Ilios (ancient Troy) in the 350s and early 360s, is a case in point. He is mentioned in a letter written by Emperor Julian (361-363). Peter Heather summarizes:

Sometime in 362/3 Pegasios, the Christian bishop of his home city, applied for a job in the new-style pagan priesthood that Julian, now entirely open about his non-Christian religious allegiance, had just begun to establish. The emperor wrote the letter to assure his officials in Constantinople that Pegasios was an appropriate candidate for the position of pagan priest. Pegasios had a reputation as a Christian bishop who had been destroying pagan temples, which made the officials want to reject his application; the emperor was writing to banish their doubts. Julian and Pegasios had first met almost a decade previously [when Julian visited Troy]. … on arrival, he was greeted by Bishop Pegasios—completely unknown to him previously—who conducted Julian to a temple dedicated to the Trojan hero Hector. Far from being destroyed, Julian wrote, ‘I found that the altars were still alight, I might almost say blazing, and that the statue of Hector had been anointed till it shone.’ The same turned out to be true of a second temple, dedicated to Athena, where Julian noticed that—unlike most Christians, who regarded pagan gods as demons—Bishop Pegasios did not cross himself or hiss to ward off evil spirits. ‘Then, on the final stop of the tour: Pegasios went with me to the temple of Achilles as well and showed me the tomb in good repair; yet I had been informed that this also had been pulled to pieces by him. But he approached it with great reverence … and I have heard … that he also used to offer prayers to Helios [in Julian’s theology, the supreme sun god] and worship him in secret.’[28]

Most bishops, admittedly, were fanatic Christians, encouraging and enforcing vigorously anti-Christian laws. But Pegasios was certainly not a unique case of “closet pagan” high-official. Many upper-class Roman had made their formal conversion, while maintaining their pagan lifestyle and interests. “Conversion, in other words, is a deceptively simple word. … Conversion to Christianity clearly meant a wide range of things to different fourth-century Romans.”[29]

Persecution and criminalization

After Julian “the apostate”, Valentinian and Valens (364-378) increased repression against non-Christian cults, often assimilated to sorcery. Intellectuals (philosophers) were specially targeted. Pagan historian Zosimus wrote in his New History IV, 14-15, regarding the Eastern part of the Empire:

The emperor … suspected all the most celebrated philosophers, and other persons who had acquired learning, as likewise some of the most distinguished courtiers, who were charged with a conspiracy against their sovereign. This filled every place with lamentation; the prisons being full of persons who did not merit such treatment, and the roads being more crowded than the cities [with exiles fleeing persecution]. … All persons accused were either put to death without legal proof, or fined by being deprived of their estates; their wives, children, and other dependants being reduced to extreme necessity. … informers, together with the rabble, would enter without control into the house of any person, pillage it of all they could find, and deliver the wretched proprietor to those who were appointed as executioners without suffering them to plead in their own justification.

Valens and Valentinian purged the administration of all pagans, and initiated a severe persecution of the non-Christian philosophers, who were “nearly all exterminated”, to the satisfaction of Christian historian Sozomen (Ecclesiastical History, VI, 35), who writes that persecution tightened under Theodosius (379-395):

For when the emperor saw that the habit of past times still attracted his subjects to their ancestral forms of worship and to the places they revered, at the beginning of his reign[379] he stopped them entering and at the end destroyed many of them. As a result of not having houses of prayer, in the course of time they accustomed themselves to attend the churches; for it was not without danger to offer pagan sacrifice even in secret, since a law was issued fixing the punishment of death and loss of property for those who dared to do this. (Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, VII, 20)[30]

Pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus tells of a full-scale purge in Antioch, targeting the city’s intellectuals, who lived as with “swords hung over their heads”:

the racks were set up, and leaden weights, cords, and scourges put in readiness. The air was filled with the appalling yells of savage voices mixed with the clanking of chains, as the torturers in the execution of their grim task shouted: “Hold, bind, tighten, more yet.” (The Later Roman Empire, XXIX, 23).[31]

The year 391 was marked by the destruction of the Serapeum (temple of Serapis) in Alexandria. It was “a momentous event,” according to Edward Watts (The Final Pagan Generation),

second perhaps only to the Gothic sack of Rome in 410 for the amount of attention it received from contemporary sources. In the same way that the sack of Rome shocked an empire unaccustomed to questioning its military superiority, the disappearance of Serapis’s temple in Alexandria highlighted the vulnerability of large centers of traditional religion that had once seemed a permanent fixture of Roman life.[32]

When in 392, the Western emperor Valentinian II was found hanged in his residence in Vienne, Gaul, a pagan party, led by the prefect of Rome and a Frankish general, proclaimed a certain Eugenius as emperor in the West. Theodosius, Valentinian’s brother-in-law, responded on November 8, 392 with a universal and comprehensive ban on every form of pagan worship, including the offerings of incense, wine, and even garlands hung on trees, threatening offenders with confiscation of property. It was even forbidden to honor the household gods and the lares in private. The imperial police could search and seize the property of offenders. “Let no one go into temples, look at temples, or raise their eyes to images formed by mortal works, lest they be guilty of divine and human punishment” (Theodosian Code, Book 16, X, 10-11). According to pagan historian Zosimus, under Theodosius, “the temples of the gods were everywhere violated, nor was it safe for anyone to profess a belief that there are any gods, much less to look up to heaven and to adore them” (New History, IV, 33). The pagan forces were defeated at the battle of the Frigidus in September 394, followed by an intense purge.

Theodosius died in 395. There was much destruction of temples under his sons Honorius and Arcadius: the temple of Artemis in Ephesus, one of the seven wonders of the world, was leveled to the ground in 401. From 407, laws were passed ordering the systematic destruction of temples and shrines on imperial estates. Non-Christian writings were censored, and their authors charged, to the relief of Augustine, who mentions that, after he published the first three books of The City of God, he heard that some persons :

were preparing against them an answer … but were waiting a time when they could publish it without danger. … Wherefore, whoever he be who deems himself happy because of license to revile, he would be far happier if that were not allowed him at all. (Book V, chapter 26)

In 435, private landowners were ordered to erase all traces of paganism on their lands. Bishops could count on the active participation of violent monks, who “were taking into their own hands the enforcement of various imperial laws against pagan sacrifice” (Michael Gaddis).[33] They believed that demons lodged in the statues of the divinities, which had to be exorcised by gouging out their eyes and/or marking them with a cross on their foreheads. Exceptionally, God himself would intervene, according to a hagiographic tale about saint Porphyrius, the bishop of Gaza from 395 to 420: when a group of Christians carrying a cross walked by a statue of Aphrodite, “the demon that dwelt in the statue beholding and being unable to suffer the sight of the sign which was being carried, came forth out of the marble with great confusion and cast down the statue itself and broke it into many pieces” (Vita Porphyrii §61). More often, hammers were required (watch this interesting video, “Why Ancient Christians Destroyed Greek Statues”). According to MacMullen, these armies of zealots, “summoned forth from monasteries and basilicas by their leaders and watched benevolently or avenged by army units,” went about “destroying no doubt more of the architectural and artistic treasure of their world than any passing barbarians thereafter.”[34]

Torture and crucifixion

Peter Heather describes the Christianization and depaganization of the Roman Empire as the work of a minority of extremely well-organized and determined activists comparable to the Bolsheviks and “the kind of one-party state model that operated in the old Soviet bloc”:

A few brave individuals always resisted systemic pressures to conform, but the vast majority—if lucky enough to have any choice at all—would always choose to join the party, because it was the only available path to the best possible everyday life for the less ambitious, and especially for those targeting fame and fortune.[35]

By the end of the fifth century, perhaps half of the Roman population had renounced heathenism, under “threats, and more than threats, of fines, confiscation, exile, imprisonment, flogging, torture, beheading, and crucifixion.” (MacMullen)[36]

The pressure still went up a notch under Justinian (527-565): “There was a great persecution of pagans, and many lost all their property,” writes Byzantine chronicler John Malalas. “A great terror was aroused … [with] a deadline of three months to be converted” (Chronicle, 18). In Anatolia, writes historian Procopius, troops were sent to eradicate all traces of paganism, and “to compel such persons as they met to change from their ancestral faith,” causing some to resist, to escape into exile, or to commit suicide; “and any of them who had decided to take on merely the name of Christian, evading their present circumstances, were, most of them, soon arrested at their libations, sacrifices, and other unholy acts” (Secret History, XI, 21-23). Under Tiberius II (578-582), notably in Phoenicia, where the commander Theophilus “seized many of them and punished them as their impudence merited, humbling their pride and crucifying and killing them.” Summoned to Edessa, the high priest of Antioch killed himself, while his associates were tortured into denouncing as his fellow-worshiper the vice-prefect Anatolius, who was brought to Constantinople around 579, tortured and crucified, according to John of Ephesus (Ecclesiastical History III, 27-32). Under the next reign, that of Mauricius (582-602), pagans were brought before the courts in every region and city, according to the Chronicle of Michel the Syrian . In Carrhae-Harran (in today’s Turkey), the bishop received the emperor’s orders to institute a persecution. “Some he managed to convert to Christianity, while many who resisted he carved up, suspending their limbs in the main street of the town.”[37]

By the time Islam started to conquer huge parts of the Eastern and Southern provinces, a mere 30 years after the death of Mauricius, the empire could be said to be fully Christianized. All other religions had by then disappeared.

All but one: Judaism was the only non-Christian religion that remained legal throughout the Roman Empire, under the strange justification that the Jews were a witness to the truth of Christianity. They compiled their Talmud (in other words they created Judaism) during the period studied in this article. They, and they alone, were allowed to mutilate the genitals of their newborn males in the name of their religion, something that pagan emperors had banned repeatedly.[38]

Main bibliography

Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100-400), Yale UP, 1984. MacMullen is universally recognized as a pioneer in the revisionist study of the Christianization of the Roman Empire over the two centuries from Constantine to Justinian. He communicates his knowledge and insights of the subject in a highly readable and often witty style. I also recommend his books Paganism in the Roman Empire, Yale UP, 1981, and Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale UP, 1997.

Alan Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, Oxford University Press, 2011. This 878-page book challenges the perspective opened by MacMullen on the resistance of the Roman aristocracy. Although his detailed counterpoints are welcome, his critical exegesis of pagan sources appears often arbitrary and inconclusive.

Peter Heather, Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, Penguin, 2023. The most recent and, in my view, the best presentation of the Christianization of the empire. Heather’s overall picture is consistent with MacMullen’s, but has benefitted from the latest research (including Cameron’s). I find his insights on the sociology and the politics of conversion very convincing. If you read only one book, I recommend this one.

Richard Fletcher, The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD, Fontana Press, 1998. This book is focused on the conversion of the Barbarians from 371, but brings some insights on the Christianization of Romans, and the Romanization of Christianity in the process. It is rather conservative in its positive assessment of Christianity and of the “process of the acceptance of Christianity”.

Michele R. Salzman, The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire, Harvard University Press, 2009. This book brings some clarification on the status, structure and mentality of the Roman aristocracy. Although accepting the general consensus that imperial pressure was the dominant factor in its conversion, the author emphasizes how class interests were negotiated in the process.

Michael Gaddis, There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire, University of California Press, 2005. A useful resource on Christian violence against pagans, although lacking consistency and a clear perspective.

Catherine Nixey, The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, Pan Books, 2017. A good read and a best-seller on the subject, but with a strong bias against Christianity and a passionate tone that often impairs scholarly objectivity.

Notes

[1] MacMullen, Paganism in the Roman Empire, p. xii.

[2] Alan Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, p. 26.

[3] Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale UP, 1997 , p. 24.

[4] Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100-400), Yale UP, 1984, p. 6.

[5] Ernest Renan, Histoire des origines du christianisme, 1863-1881.

[6] Richard Fletcher, The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD, Fontana Press, 1998, p. 35.

[7] Diana Bowder, The Age of Constantine and Julian, Barnes & Noble, 1978, p. 80.

[8] Firmicus Maternus, The Error of the Pagan Religions, trans. Clarence A. Forbes, Newman Press, 1970, x.7, xxviii.6.

[9] Peter Heather, Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, Knopf, 2023, Penguin, p. 83.

[10] Pierre de Labriolle, La Réaction païenne. Étude sur la polémique antichrétienne du Ier au Ve siècle, 1934, p. 496.

[11] MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire, p. 109.

[12] Ramsay MacMullen, Paganism in the Roman Empire, Yale UP, 1981, p. 34.

[13] MacMullen, Paganism in the Roman Empire, p. 24.

[14] MacMullen, Paganism in the Roman Empire, p. 27.

[15] Peter Heather, Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, Penguin Books, 2023, p. 115.

[16] Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale UP, 1997, p. 69.

[17] Alan Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, Oxford UP, 2011, p. 29.

[18] Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100-400), Yale UP, 1984, p. 50.

[19] Alan Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, Oxford UP, 2011, p. 61.

[20] Charles Freeman, The Closing of the Western Mind: the Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason, Random House, 2005, p. 9.

[21] Michael Gaddis, There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire, University of California Press, 2005 , p. 31.

[22] Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, op. cit., p. 48.

[23] Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, op. cit., p. 42.

[24] Michele R. Salzman, The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire, Harvard UP, 2009, pp. 1-2, 6, 17, 27.

[25] Peter Heather dans Christendom : The Triumph of a Religion, Knoff, 2023, pp. 100, 82, 104.

[26] MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire, p. 115.

[27] Richard Fletcher, The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD, Fontana Press, 1998, p. 36.

[28] Heather, Christendom, op. cit., pp. 64-67.

[29] Heather, Christendom, op. cit., p. 66.

[30] Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, op. cit., p. 71.

[31] Catherine Nixey, The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, Pan Books, 2017, p. 162.

[32] Edward J. Watts, The Final Pagan Generation, University of California Press, 2015.

[33] Gaddis, There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ, op. cit., p. 218.

[34] MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire, p. 119.

[35] Heather, Christendom, op. cit., p. 104.

[36] MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism, op. cit., p. 72.

[37] All quotes in this paragraph are borrowed from MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism, op. cit., pp. 27-28.

[38] “Circumcision alone will preserve the Jewish nation for ever,” wrote Baruch Spinoza in Theological-political treatise, chapter 3, §12, Cambridge UP, 2007, p. 55.