House of Edification or House of Horrors?

Until I visited San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art (SF MoMA), it had never occurred to me to think of an art museum as a sinister thing. SF MoMA has seven floors in which hundreds of people float through the exhibits in reverent, scholarly silence. The visitors take pictures of “art installations” made of broken mirrors, fallen café lights, red rectangles, clay brains stacked in pyramids, warbling speakers, nudes crushed into geometrical shapes, spidery electrical amoebas, and biblical passages alphabetized by letter. During my three hours in the museum, I noticed only one incredulous person as she laughed at a piece of framed graph paper. The only other negative reaction I witnessed came from my then 10-year-old brother, who leaned over and whispered, “This is making me so scared and sick.” Otherwise, an aura of undisturbed acceptance prevailed.

Last year, the Turner Prize, an annual award for contemporary artistic achievement, was granted to Jasleen Kaur for her work “Alter Altar.” SF MoMA would have gobbled it up. The central feature of the piece was a red Ford Escort draped in a giant lace doily. Past ribbons of the Turner Prize have been affixed to sex dolls, a solid concrete house, and bisected dead animals.

Recently, while studying sculpture in Florence, Italy, my composure was continually rattled by my fellow students, who took the course as an opportunity to pull similar postmodern pranks on a classical bust: adding horns, painting the face a garish yellow, and making the “artistic decision” to eradicate the nose. Art has become so much a platform of self-expression that the discipline required to acquire traditional artistic skills is no longer valued. “Postmodernism was born of skepticism and a suspicion of reason,” according to the website of the Tate Modern, a contemporary art museum in the United Kingdom. Tate describes postmodernism as, “Anti-authoritarian by nature…[it] refuses to recognize the authority of any single style or definition of what art should be. It challenges the notion that there are universal certainties or truths.”

The Tate’s definition of postmodernism is, in other words, the opposite of true art. True art is grounded in authority, the authority of universal truth and universal beauty. In his book How Shall We Then Live? (1976), American theologian Francis Schaeffer claims that without absolutes or universal truths, particulars will have no power. Thus, according to Schaeffer, if art cannot retain the standard of ultimate truths (including an understanding of morality, divine authority, and human dignity) then it, too, loses its power.

This doesn’t mean that art must only orbit religious or spiritual themes. A painting does not have to depict the Madonna and Child to offer a testimony of youth, death, love, grief, hope, redemption, brotherhood, light, and other facets of the human experience. And respect for authority doesn’t mean stifling creativity and innovation, which are essential to art’s advancement. But change with a transcendental priority will result in progress, while rebellion without a greater purpose is simply chaos—a goblin that has never paved the road to improvement.

Ultimately, art must edify. The words “edify” and “edifice” come from a Latin word meaning “to build or improve.” An edifice is a dwelling place and edification is the process of making that place into a suitable abode. As physical buildings need walls, floors, and furnishing, so art needs boundaries, meaning, and hope if it is ever to promote the edification of those who create or observe it. According to Tate’s definition, postmodern art rejects all three of these things, and therefore it cannot edify.

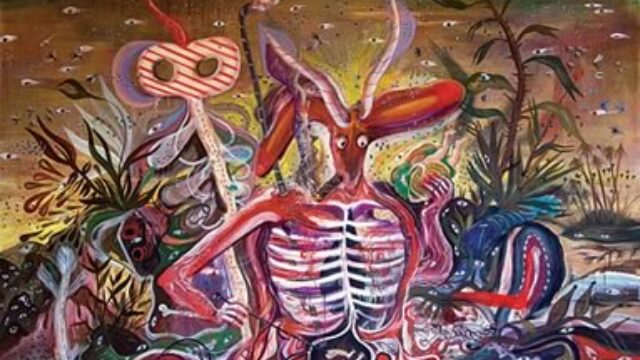

Gene Edward Veith, Jr. author of State of The Arts: From Bezalel to Mapplethorpe, writes that [postmodern] “artists prostitute themselves and their art in so far as they sell out their integrity for success with the art establishment.” Veith would agree that the boundaries of privacy and self-care are not only pushed but erased. For example, Marc Quinn used his own blood to make six frozen casts of his head called Self, Millie Brown drank dyed milk before vomiting on a canvas, and the artist “Orlan” surgically altered her face by embedding silicone implants in her temples—all in the name of art. In another breach of boundaries, Edward Weston photographed his naked son, and later Sherrie Levine photographed this photograph, which somehow secured her foothold to fame. But as Ralph Moody expressed in his autobiographical novel Little Britches, “If [a man] tears boards off his character house and burns them to keep himself warm and comfortable, [it] soon becomes a ruin.” Postmodern art has freedom, but it is the freedom of a body rid of its skeleton. There can be no forward motion without a direction to follow, and unable to move outside of self, the boneless, postmodernist groping for success has a proclivity for self-destruction rather than regeneration.

Postmodern art aspires to no higher meaning. Some postmodernists assign low meaning to their work, whether it is entertainment, fun, prescribed meaninglessness, circumstantial background, or private interpretation. But what is missing is any connection to transcendental truth. Without a beforelife or an afterlife, suddenly the world shrivels into this tiny, myopic, arbitrary scope where everything collapses into the fleeting and fractional now. That desperate limitation produces in man a mad scramble to make some original mark on the earth, propelling “artists” to extremes as they try to be the most shocking of the shocking, the most bizarre of the bizarre, throwing the loudest, most colorful fit possible so that a few heads will turn and see. That is a low meaning in the pit of tragedy. When transcendental significance is snipped away, artistic work sinks into temporal bric-a-brac that cannot possibly spur people towards betterment.

Our current era of art also lacks hope. The scholar Stephen Hicks poses this question: “When has art in the twentieth century said anything encouraging about human relations, about mankind’s potential for dignity and courage, about the sheer positive passion of being in the world?” When confidence in the potential to be better is lost, hope, by definition, goes with it. Beauty is the embodiment of hope. Postmodernism is a taxi for nihilism rather than a path for beauty and restoration. This was glaringly obvious when the Trapholt Museum in Denmark exhibited live goldfish swimming in blenders plugged into a power source, waiting for the passerby to succumb to his destructive urge and flip the switch. Similar pieces include notorious Marcel Duchamp’s signed urinal and a vandalized copy of the Mona Lisa, a painting known for its portrayal of the golden ratio, also known as the “beauty equation.” Philip Reiff uses the term “deathwork” to describe pieces like Andres Serrano’s crucifix immersed in urine, an object subverted from veneration to desecration. Beauty has been eaten by the Beast.

“Art was a vehicle that created anxiety. It was about whether you could draw something just perfectly,” the American pop artist Jeff Koons recalled of his early experience as an artist. “But at the end of the day what art really is, is a vehicle of acceptance.” Yet anything, given the proper atmosphere, can be made into a vehicle of anxiety. For example, I am not mathematically or scientifically minded and I find the idea of logarithms or kinematic viscosity paralyzing. But I cannot change the laws of algebra or physics to cater to my weak ability. The victorious solution lies in a deeper commitment to improvement and in rising to meet the rigor of these subjects on their own terms. What Koons and his cronies do is dismantle art and bring it down to their own subpar level, turning angst into the accepted basis. Acceptance has become a primary topic in our society today. When someone refrains from accepting a dismantled standard, they are immediately labeled as racist, sexist, unsanitary, discriminatory, repressive, or archaic.

Of course, this carnivorous postmodern disease infects more than just our visual art, architecture, music, dance, and film. Loss of boundaries is clear in the wreckage of families, the lack of meaning in the cheapness of our language, the absence of hope in apathetic lifestyles, climbing suicide rates, and widespread depression. Without intending to grossly exaggerate and understanding that many people are untouched by these blanket generalizations, it remains the case that artwork reflects the society from which it came. If that is so, postmodern art is the voice of the boundary-less, the meaning-less, and the hope-less. In other words, postmodernism is a homeless voice—estranged from edification. Still, as Veith argues in his scholarship, postmodernism is not a dead end, but merely a wrong turn. That house of edification can be rebuilt if our society again latches on to unshaken absolutes and stops circling the drain.

https://chroniclesmagazine.org/web/house-of-edification-or-house-of-horrors