Spiro Agnew’s Surprising Embrace of Antisemitism

Spiro Theodore Agnew began his career as a respected establishment figure, but after his resignation as 39th vice president of the United States his post-political career took an interesting anti-Zionist turn.

Agnew began life in Baltimore in 1918 as the son of Theodore Anagnostopoulos, a Greek immigrant who ran a local diner, and Margaret Akers, a Virginian with deep American roots. He attended Johns Hopkins University, interrupted his studies to serve as an Army officer in France during World War II, earned a Bronze Star, then completed a law degree at the University of Baltimore in 1947.

By the end of the 1950s, Agnew had risen from the Baltimore County Zoning Board of Appeals to electoral success, becoming County Executive in 1962 and Maryland’s governor in 1966. As governor, Agnew combined reformist initiatives such as a graduated income tax with pointed rhetoric denouncing the antiwar movement and the liberal media, a combination that impressed Richard Nixon’s campaign strategists.

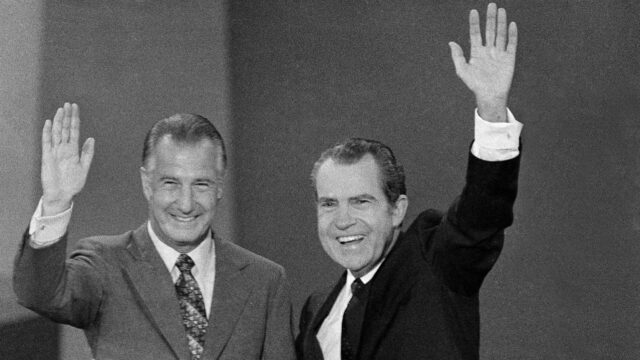

Nixon chose the little known Marylander as his running mate in 1968. Agnew’s blunt television attacks on Vietnam War protesters, journalists, and “radical liberals” electrified portions of the electorate and yielded the era’s most memorable insult directed against politicians critical of the Nixon administration, “nattering nabobs of negativism.” He cultivated the image of champion of the silent majority while privately shifting rightward, ready to defend administration policies with a ferocity that sometimes overshadowed the president himself.

Re-elected with Nixon in the 1972 landslide, he seemed positioned to inherit the Republican mantle should Watergate consume the Oval Office. Instead, Agnew’s own scandal led to his downfall.

While Senate hearings probed the Watergate break-ins, federal prosecutors in Baltimore uncovered a cash-for-contracts network dating to Agnew’s time as county executive. Witnesses described envelopes filled with bills exchanged in his state-house office and, astonishingly, in the Executive Office Building after he became vice president. Insisting the allegations were “damned lies,” he nevertheless negotiated a plea of nolo contendere to a single felony count of tax evasion on October 10 1973, paid a $10,000 fine, and resigned, becoming only the second vice president in American history to leave the post mid-term. Gerald Ford soon replaced him, and Watergate rolled on.

The fall was both personal and public. Friends recalled that Agnew now spoke of betrayal and conspiracy, convinced that powerful enemies had forced him out so he would not succeed a wounded Nixon. Among those adversaries he named were “Zionists.” These accusations of a Zionist conspiracy soon leached into public discourse. In 1976 Agnew re-emerged with a political thriller titled “The Canfield Decision”, whose plot hinged on a Jewish media cabal sabotaging an American vice president.

During his promotional tour, he told the Washington Star that half of individuals in the “ownership and management policy posts” of the national impact media are Jewish, a power that had produced a catastrophic U.S. approach to Middle East governance. During an appearance on NBC’s “Today” program in 1976, he expanded the charge: “I feel that the Zionist influences in the U.S. are dragging the United States into a rather disorganized approach to the Middle East … there is no doubt that there has been a certain amount of Israeli imperialism taking place in the world.” Such remarks caught the attention of organizations skeptical of Jewish influence, while mainstream Jewish leaders naturally denounced Agnew’s statements. Benjamin R. Epstein, then-national director of the ADL, excoriated Agnew’s comments as “irresponsible anti‑Semitic statements maligning American Jews and the American press.” Epstein also accused him of “parroting the Arab propaganda line” and remarked that “this comes as no surprise in light of his activities on behalf of Arab petrodollar countries seeking to invest in the United States.”

Similarly, Rabbi Alexander Schindler, chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, declared: “Spiro Agnew has disgraced himself once again with his despicable statement, so redolent of the venom and slander we have come to expect from the anti‑Semitic lunatic fringe.”

The former vice president’s comments were more than isolated flashes of pique; they signaled a durable ideological pivot. Agnew’s hostility toward world Jewry led him to court the oil wealth of the Arabian Peninsula to bankroll his anti‑Zionist pursuits. He would soon begin to broker American construction and engineering contracts in Saudi Arabia. The most revealing artifact of that relationship surfaced in 2019 when reporters located a ten-page letter dated August 25, 1980, in his personal papers.

Addressed to Crown Prince Fahd bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, the document requests “an interest free, two million dollar loan” that would be channeled through a Liechtenstein account so Agnew could continue his fight against the “Zionist enemies who are destroying” the United States. Agnew also congratulated Fahd on a “clear and courageous call to jihad” after Israel declared Jerusalem its capital.

After that letter was published, Agnew largely disappeared from headline politics yet never retracted his assertions. Agnew would occasionally do interviews throughout the 1980s where he repeated charges of Zionist media control and dual loyalty among American Jews. Agnew spent his remaining years shuttling between California and Maryland, consulting for foreign clients, battling tax authorities, and publishing a memoir in which he laid out his side of the story regarding his fall from grace. When he died of leukemia in 1996, obituaries noted the remarkable arc from war veteran to governor to vice president to convicted felon.

Despite President Nixon’s candid remarks of Jewish influence in American politics (see also here and here), his administration featured a remarkable cadre of Jewish officials occupying high-level national security and advisory roles—among them Henry Kissinger (National Security Advisor and later Secretary of State), Leonard Garment (White House Counsel), Herbert Stein (Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers), and speechwriters like William Safire and Ben Stein, along with influential informal advisers such as Max Fisher.

One of Nixon’s most consequential decisions was authorizing Operation Nickel Grass, a massive emergency airlift of over 22,000 tons of military supplies to Israel during the October 1973 Yom Kippur War. This decisive intervention prevented Israel’s potential defeat by replenishing its frontlines and offsetting Soviet support for Arab forces.

Yet even the presence of Jews in prominent positions in the Nixon administration and Nixon’s historic gesture on behalf of Israel did little to shield Nixon and Vice President Agnew from mounting criticism and pressure from both the media and political opponents.

While the Jewish officials from the Nixon administration pursued relatively unblemished political paths afterward, the “fall-goyim” in Nixon and Agnew paid the ultimate price—spending the remainder of their lives as targets of negative coverage and historical censure.

Time and again the Nixon and Agnew experience reveals the enduring axiom: with Jews you lose.