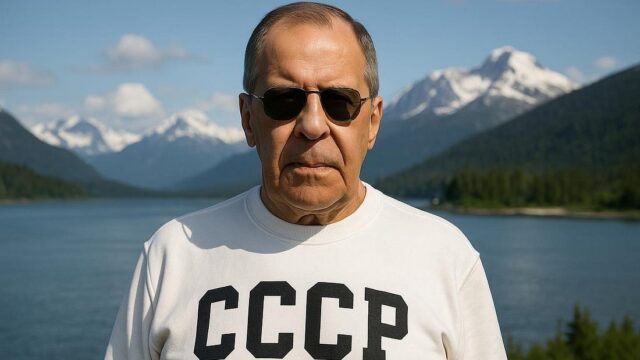

Lavrov’s CCCP Sweater in Alaska Signals the Return of Empire

Sergey Lavrov stands before the glacial immensity of Alaska, wearing a white sweater stitched with the letters CCCP, a relic-sigil of a vanished order that once held half the planet in its grasp. The tundra wind cuts around him as if circling an imperial monument; the cold is not only of climate but of memory: the unmelting frost of Stalin’s steel plans and the granite grip of Soviet geopolitics. This scene binds the geography of Russian America to the spectral cartography of the USSR, as if the Bering Strait were a seam between two epochs. Lavrov’s stance has the calm defiance of a commissar surveying a new frontier, his chest a banner for the empire that industrialized itself at breakneck speed, crushed enemies foreign and domestic, and stood as the eastern pillar in a divided world. The letters are black, the sweater white: a monochrome flag for a multipolar dawn.

The timing is calculated. Trump and Putin meet in Anchorage — a city once distant from the Kremlin, yet still within the orbit of Russian historical reach — while Lavrov’s attire collapses centuries into the present moment. This is where German National Bolshevik Ernst Niekisch’s vision of a German-Russian alliance against Western liberalism mutates into the 21st century’s multipolar playbook: not armies marching in joint columns through Europe but symbols crossing continents to puncture the West’s psychological monopoly. Lavrov wears the CCCP as Russian punk poet and National Bolshevik Party leader Eduard Limonov once wrote of wearing defiance itself, parading an identity the West believes buried. Alaska, sold by Russia to the United States in 1867, returns as a stage for the clash of empires reborn, where every handshake between Moscow and Washington is shadowed by an old imperial ledger. The photograph works like propaganda art from the Soviet era, each detail loaded: the mountains as the fortress wall, the sweater as the manifesto, the man as emissary of something that refuses to vanish.

The CCCP across Lavrov’s chest is less nostalgia than a coded threat. Stalin’s USSR was never just a socialist project; it was an imperial megastructure in red granite, its columns built from the fusion of Marxist universalism with Tsarist territoriality. Niekisch saw in Soviet power a template for a disciplined, collectivist state immune to the rot of Western individualism, and here, decades later, Lavrov carries that charge into the arena of multipolarity. This is National Bolshevism in soft focus: no tanks on the streets of Berlin but an image designed to weaponize history, to remind the viewer that the Soviet Union’s fall was only a maneuver in a longer campaign. Limonov’s exile novels turn into a kind of manual here, each page about betrayal, endurance, and the refusal to dissolve into cosmopolitan anonymity. In this frame, the sweater says: the USSR as an idea is portable, it survives in the bloodstream, it can walk across Alaska without losing momentum.

Beneath this theater lies the summit’s brittle reality. Reports hint at ceasefires held together by nothing but the desire to claim a headline, of “land swaps” that bring to mind old imperial partitions, of Europe’s exclusion from the table like a defeated province. In Niekisch’s terms, this is the moment when Atlanticism — his mortal enemy — looks most gaunt, as Washington and Moscow negotiate above the heads of smaller states. Stalin once played Roosevelt and Churchill against one another while securing his sphere; now, the maneuver is subtler but carries the same imperial grammar. Lavrov’s CCCP is the old signal flag, raised not in defiance of Washington but as a reminder that Moscow can still dictate the terms of peace and war in ways no Brussels technocrat can match. It is Stalin’s ghost smiling behind tinted sunglasses, watching a new alignment form in the permafrost.

We are in the new Age of Empires, where conquest is written in symbols rather than troop movements, but the logic remains the same. The Soviet Union as imperial structure — centralized, ideologically armed, territorially hungry — provides the blueprint for Russia’s role in the multipolar order. Niekisch would have seen this as the vindication of his Eastward turn, an assertion that the “imperial idea” must outlive the political form it once wore. Limonov would have called Lavrov’s sweater an “act of literature,” a live performance of geopolitics in which every stitch mocks the neoliberal order. This is imperial nostalgia transmuted into strategic performance art, the kind that bypasses policy briefs and lodges itself directly in the imagination of friend and foe alike.

And so the photograph, the meeting, and the setting form a triptych of this new epoch. Alaska’s mountains recall the last time Russian imperial banners flew over this land; the CCCP recalls the decades when the Soviet Union bent half the world into its orbit; the handshake with Trump recalls the transactional coldness of all imperial diplomacy. Multipolarity is born here as an image, a gesture, a suggestion that empire can return dressed in sweaters rather than uniforms. Stalin’s map, Niekisch’s theory, Limonov’s performance: these are the raw materials. Lavrov, in sunglasses and Soviet letters, is the courier. The Age of Empires lives again, and its burning frost reaches from Siberia to the Alaskan coast.

https://www.eurosiberia.net/p/lavrovs-cccp-sweater-in-alaska-signals-the-return-of-empire