Twitter Files: The Muzzling of Charlie Kirk

At a crucial juncture in the 2020 presidential election, the Washington Post used a tried-and-true method to pressure Twitter to remove Kirk.

The New York Times obituary of Charlie Kirk, “Charlie Kirk, Right-Wing Force and a Close Trump Ally, Dies at 31” will go down as an infamous entry in the genre for many reasons. It’s an obvious understatement/provocation to write “Dies at 31” in a headline about a man assassinated by rifle round to the neck. The Times also leaned on the worn trope of alleging racist or anti-Semitic comments without elucidating them (“He tweeted relentlessly with a brash right-wing spin, including inflammatory comments about Jewish, gay and Black people”), a tendency that’s been common in coverage today. Then there was this:

Mr. Kirk rose even further into the conservative stratosphere during the early days of the pandemic, when he was quick to attack the World Health Organization — which, in his typical fashion, he called the “Wuhan Health Organization” — accusing it of hiding the source of the Covid virus and claiming that it had emerged from a Chinese lab in the city of Wuhan. He later rallied opposition to school lockdowns and mask mandates.

He was so vocal in his willingness to spread unsupported claims and outright lies — he said that the drug hydroxychloroquine was “100 percent effective” in treating the virus, which it is not — that Twitter temporarily barred him in early March 2020. But that move only added to his notoriety and seemed to support his claim that he was being muzzled by a liberal elite.

The notion that Kirk was “so vocal” in his willingness to spread “unsupported claims and outright lies” that it led to his temporary banning on Twitter seemed a strange thing to emphasize in an obituary. The quote about hydroxychloroquine being “100 percent effective” notwithstanding, Kirk wasn’t wrong (or demonstrably wrong, anyway) to criticize the WHO, lockdowns, or mask mandates. The Times also likely should have been more circumspect about its own performance in contemporaneous stories like “For Charlie Kirk, Conservative Activist, the Virus is a Cudgel,” when the paper complained about his use of phrases like “China virus” and his tweeting of a list of pre-Covid diseases named after the location of the first cases (Zika, West Nile Virus, Ebola, etc). But was Kirk “muzzled by a liberal elite”?

According to Twitter Files documents, “muzzled” might be a strong word, but “targeted” would be accurate. One episode, in which an effort was made to remove Kirk and Benny Johnson just before the 2020 Presidential Election, stands out. Twitter understood this was a high-profile decision and copied the top executives in the firm, as well as Twitter’s “US GOV TEAM,” on its decision-making process. In the most damning sequence, Twitter went from having zero interest to actioning hundreds of accounts linked to Kirk within hours, after receiving a query from The Washington Post. Though the firm had a tough time linking Kirk himself to wrongdoing, he was recommended for removal, despite reservations by Trust and Safety executives. At the last minute, he was given a reprieve, only to be removed just before the election over a tweet about missing mail-in ballots.

In all, Twitter fielded at least three high-profile press queries about taking Kirk down just before the election, and one finally stuck. There’s no suggestion of an intelligence role, but it’s worth noting that a former CIA official was put in the “lead” of one of Kirk’s investigations:

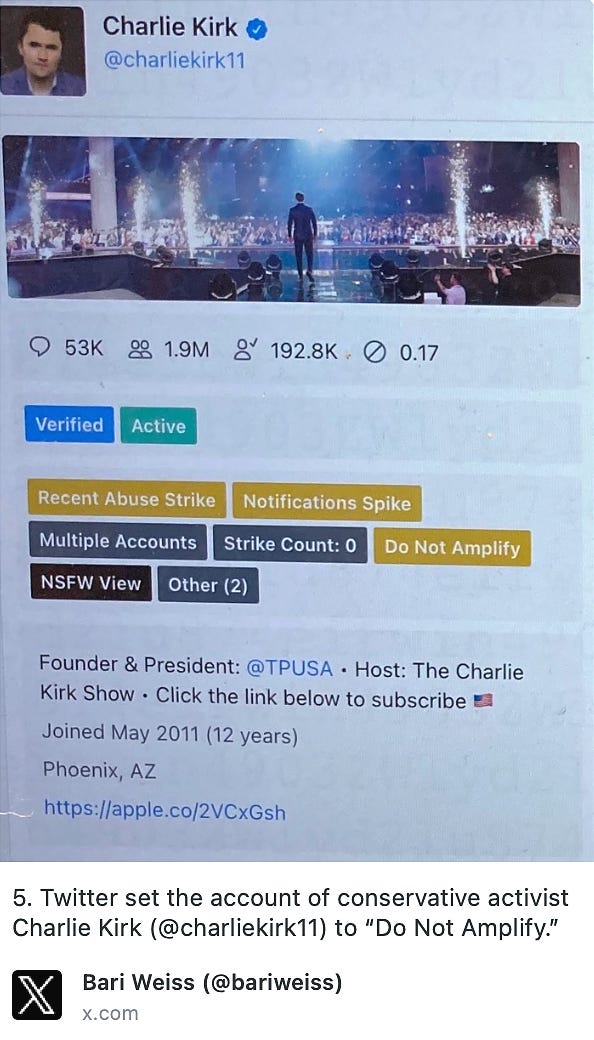

As the Times obituary notes, Kirk had a tweet deleted in March of 2020 about hydroxychloroquine. We don’t have emails about that sequence in the surviving Twitter Files. However, there are many references to Kirk elsewhere, including a photo of his “Do Not Amplify” status, and a series of exchanges in September and October of 2020, just before the election between Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

Kirk’s page was one of the first things Bari Weiss and I saw when invited to interview the temporary head of Trust and Safety at Twitter, after Elon Musk’s arrival, in the first week of December 2022:

Elsewhere, we have emails referring to an incident involving an (allegedly) Kirk-affiliated group called Rally Forge, which was quickly dubbed an “election troll farm” in the press. This exchange shows one of the worst examples of what one Twitter executive called “the model that works.”

This was a technique developed during Russiagate by NGOs and some state actors to use the threat of negative press to induce platforms to quickly remove accounts. During the time period of the Twitter Files, nearly all of these incidents involved conservatives.

How it worked: Twitter would receive “incoming” (i.e. an unwanted query) from a reporter at a high-profile publication. Typically, Twitter would be asked whether or not it planned on taking action against accounts the reporter claimed were tied to “hostile foreign actors,” “extremists,” “disinformation,” or “inauthentic activity.” Crucially, the story was almost always essentially finished by the time Twitter got its fateful email from a reporter, often on the morning of a day on which the story was scheduled to run. Immediate comment would be demanded.

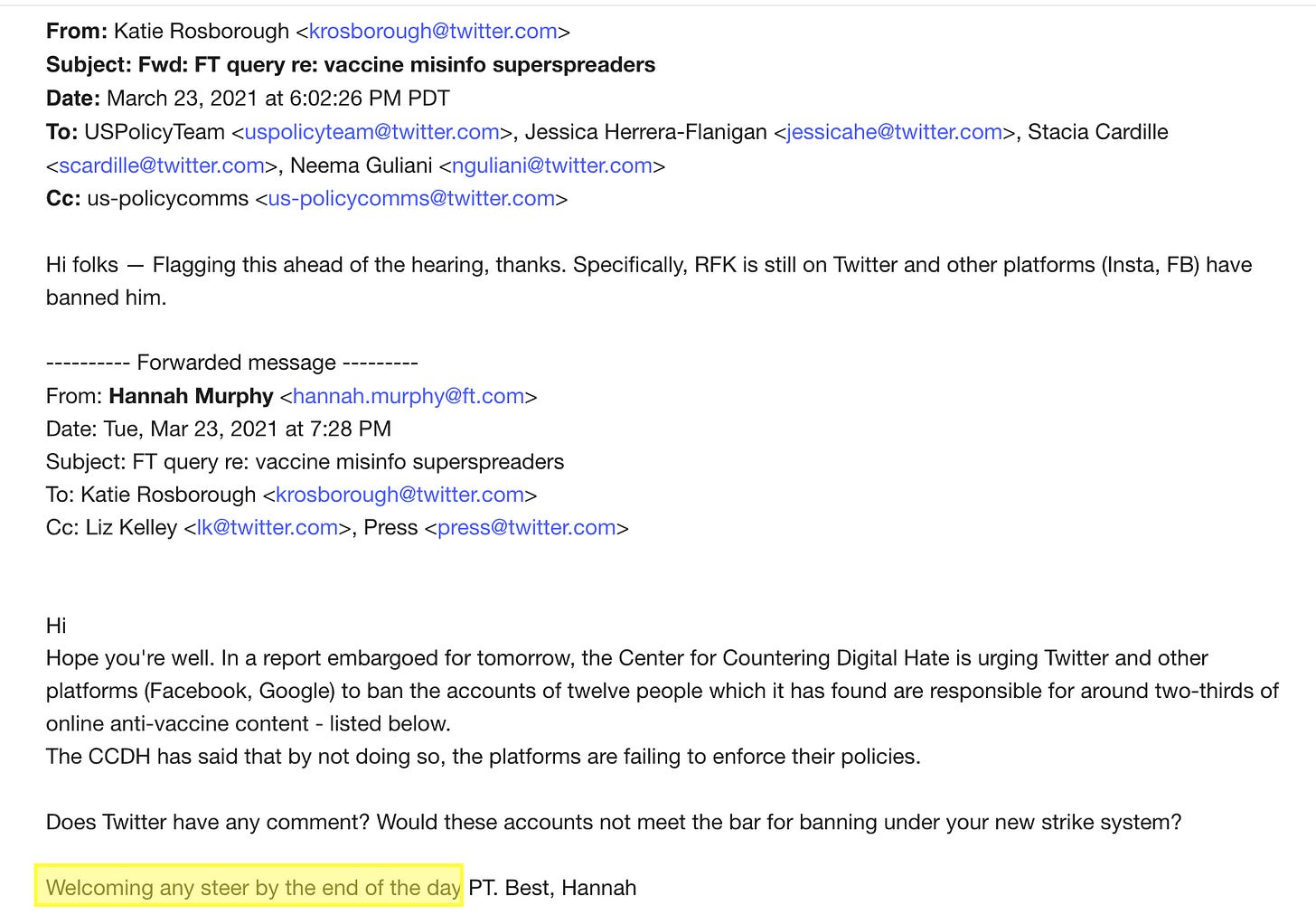

Using research that originated with the Labour Party-aligned Center For Countering Digital Hate, the Financial Times sent an email in March 2021 about a story it was planning on the so-called “Disinformation Dozen” of the pandemic. Reporter Hannah Murphy told Twitter it was “welcoming any steer by the end of the day,” meaning an indication about whether or not it planned to remove Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Joseph Mercola, Rashid Buttar, and others.

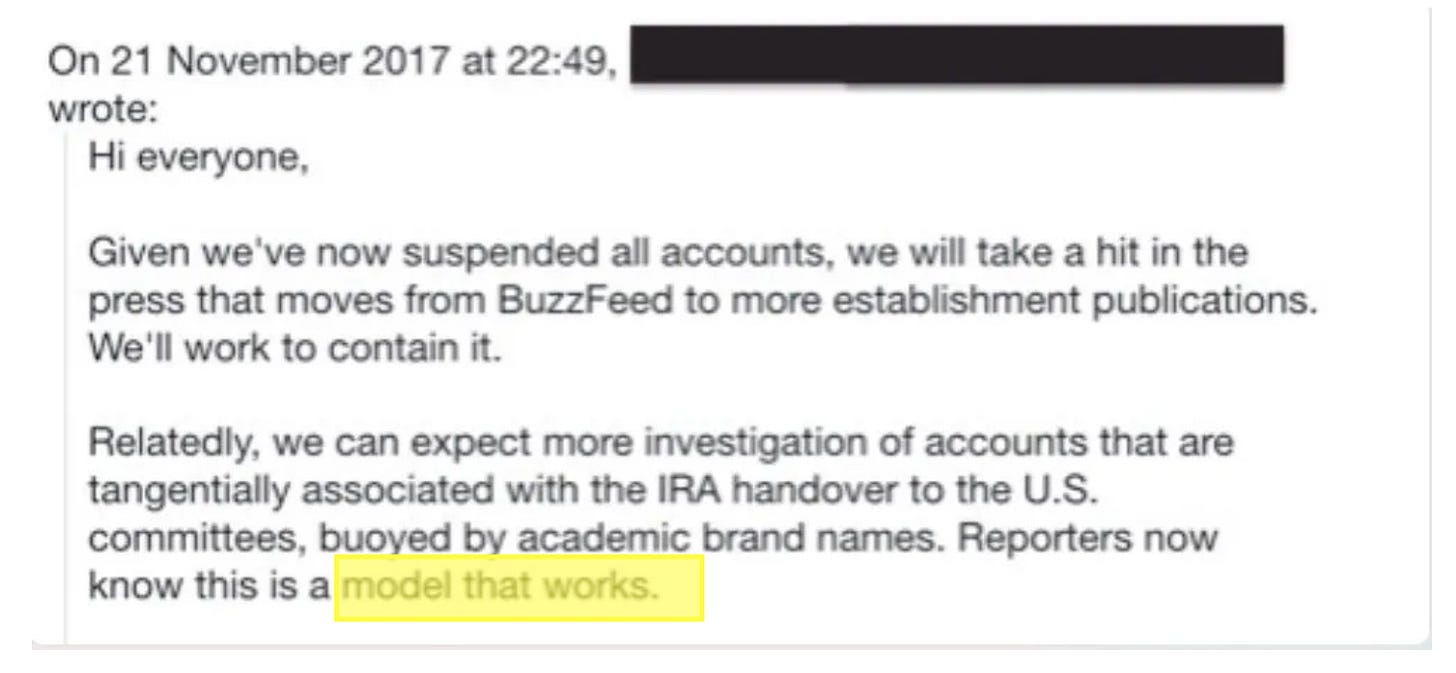

Once Twitter received such notices, it now had a gun to its head. If it didn’t remove the accounts the press asked about, the headline that night would be, “Twitter Refuses to Remove Anti-Vax Disinfo.” If Twitter could find something to remove, fast, the headline would be less painful. As one communications executive noted in a case involving Buzzfeed and Russian bots in 2017, “Reporters now know this is a model that works.”

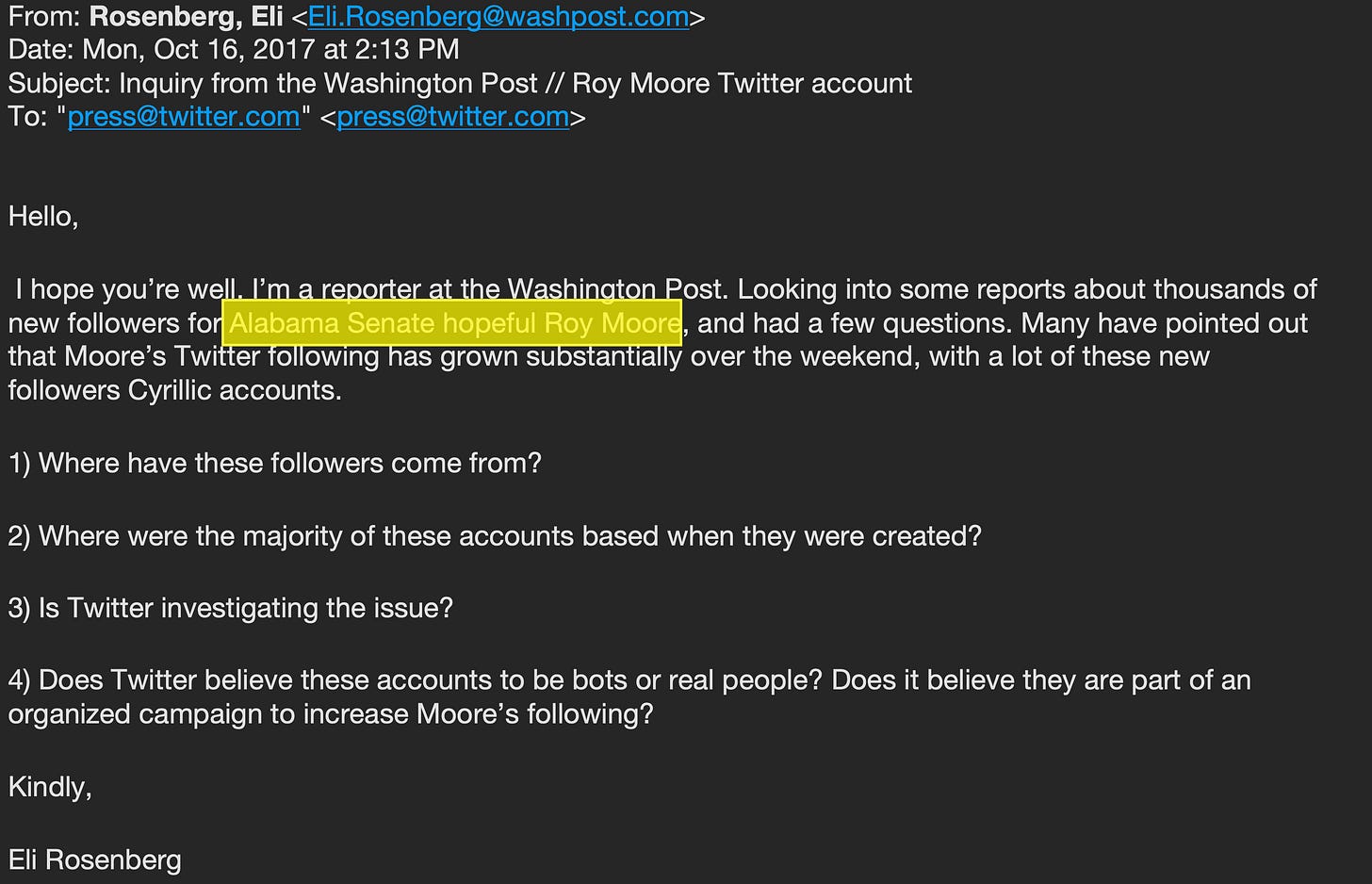

An early troubling example from 2017 involved the Washington Post asking Twitter to investigate “reports” of Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore’s Twitter following increasing, with many of the “new followers” alleged to be “Cyrillic accounts.” This later turned out to be a hoax, generated by Jonathon Morgan, CEO of a company called New Knowledge:

The “model that works” scams were more disturbing when the “research” originated from state actors like the Senate Intelligence Committee or the FBI, state contractors like New Knowledge, or from “academic brand names” at universities like Clemson, who made lists of Russians or other wrongdoers. These players would send lists to reporters, who in turn wrote to Twitter, which began caving to this technique at the height of Russiamania in 2017.

In 2020, it came for Kirk and fellow Turning Point USA influencer Benny Johnson. The subject was Rally Forge, reportedly a “sister” organization to Kirk’s 501(c)3, Turning Point USA.

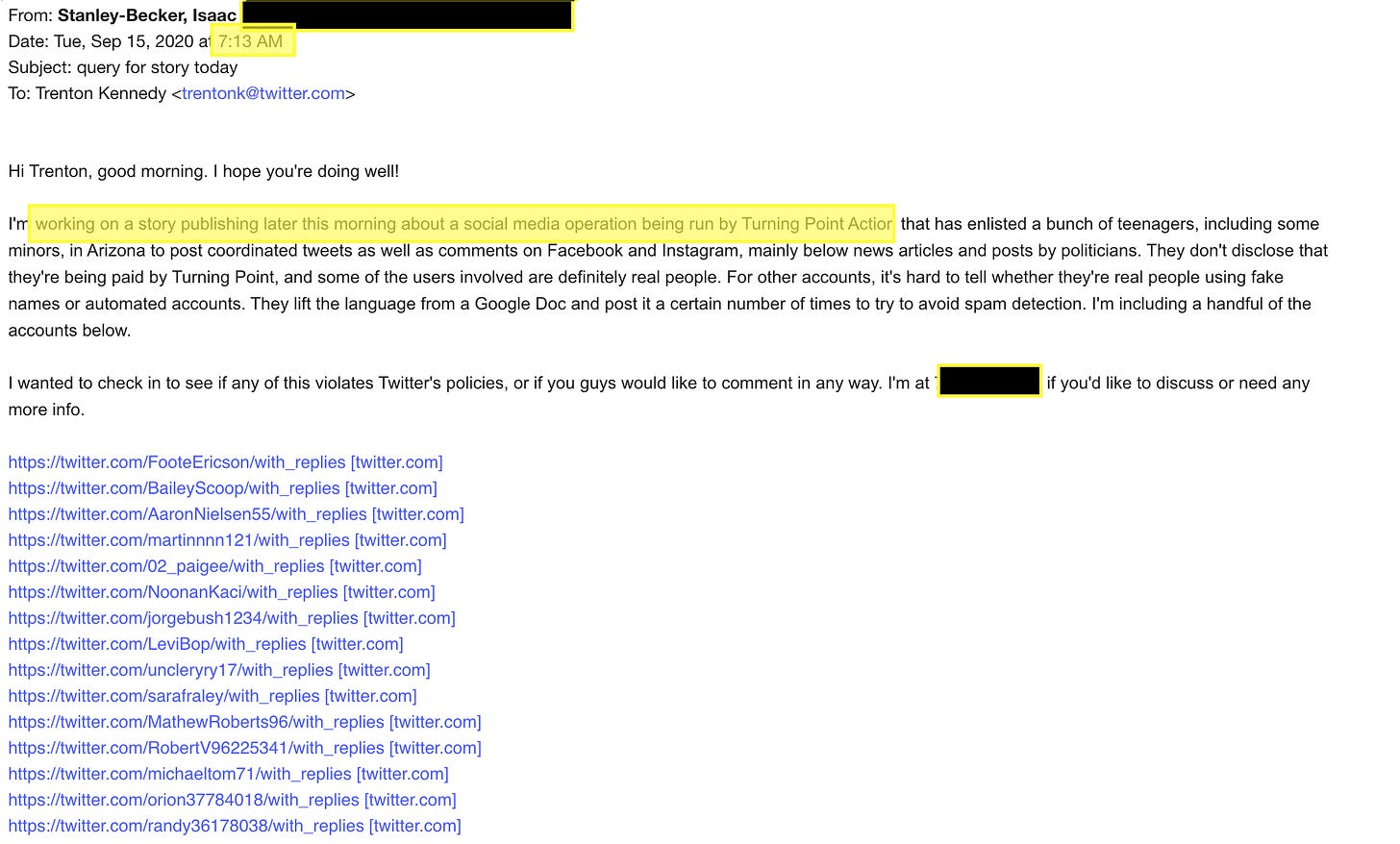

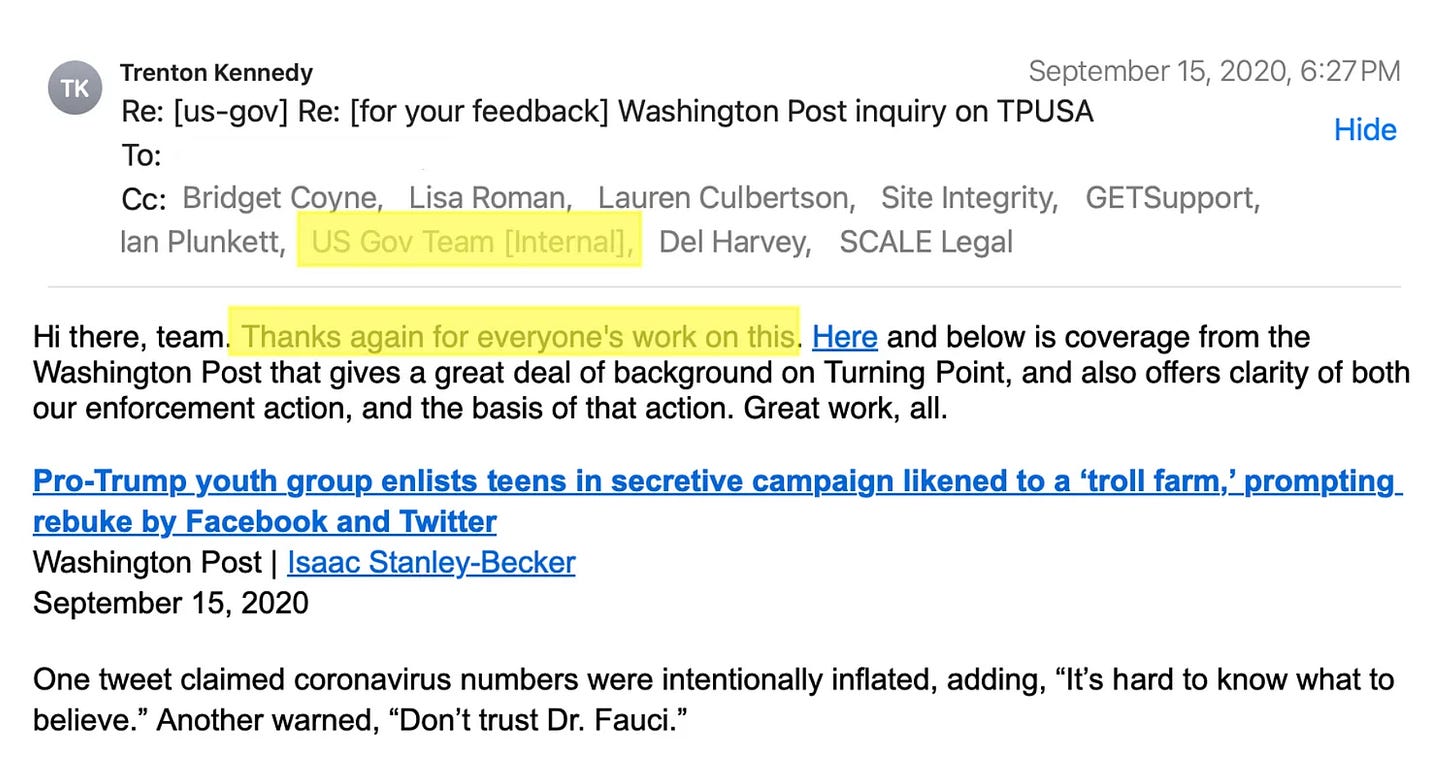

Rally Forge was accused of being deceitful by creating accounts seemingly designed to rope in Democrats, without disclosing Turning Point support. In conjunction with the “model that works” format, actions by Twitter and Facebook were prompted by a Washington Post reporter. On September 15, 2020, reporter Isaac Stanley-Becker sent a list of 20 accounts he said belonged to “teenagers” enlisted to post on behalf of Turning Point. “It’s hard to tell whether they’re real people using fake names or automated accounts,” Stanley-Becker wrote, but would Twitter “check in to see if any of this violates Twitter’s policies?”

The letter from the Post’s Becker hit the in-box of a Twitter communications executive at 7:13 AM:

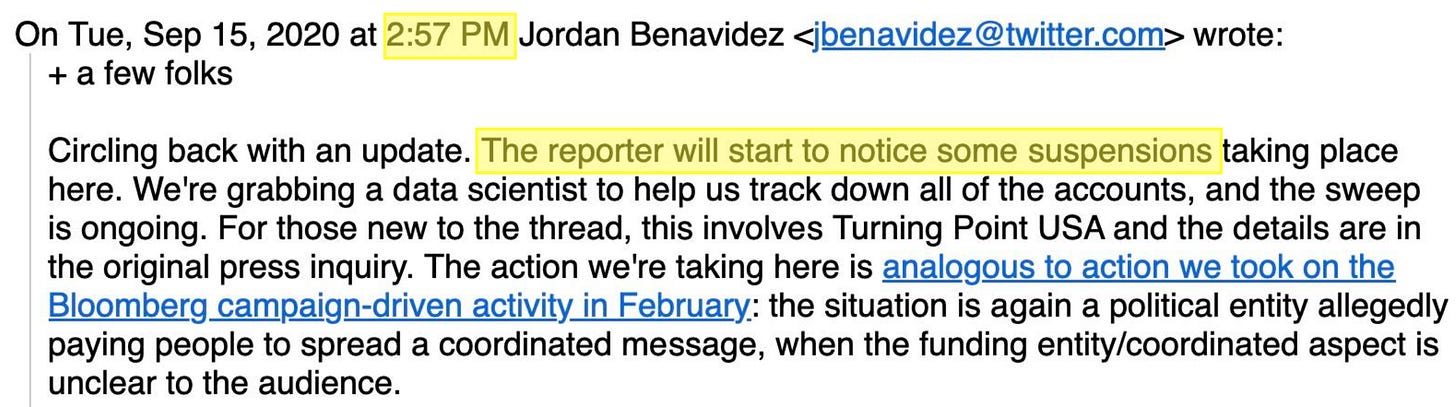

By 2:57 PM, a Trust and Safety executive told the comms department that “the reporter will start to notice some suspensions taking place here,” and “We’re grabbing a data scientist to help us track down all of the accounts, and the sweep is ongoing.”

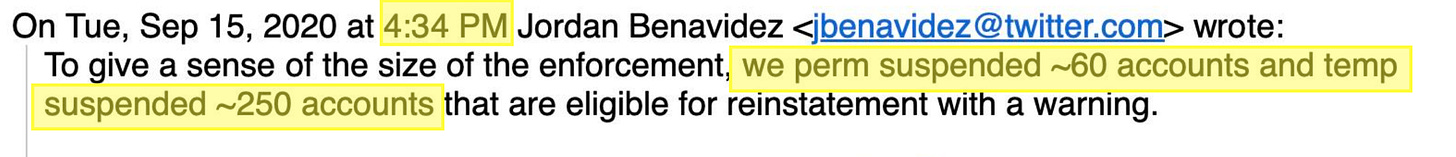

By 4:34 PM ET, the Trust and Safety department told the press office: “We perm suspended ~60 accounts and temp suspended ~250 accounts.”

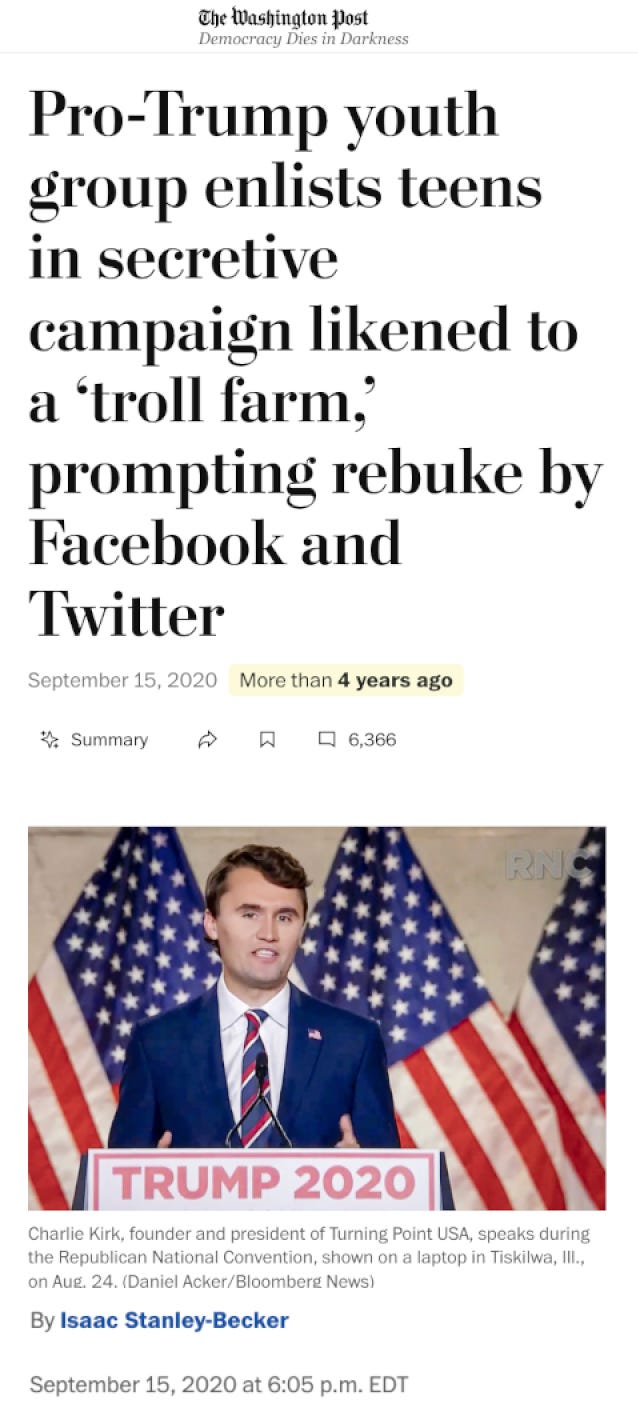

By 6:05 PM ET, ninety-one minutes later, the Post ran a story noting action by Twitter in the headline: “Pro-Trump youth group enlists teens in secretive campaign likened to a ‘troll farm,’ prompting rebuke by Facebook and Twitter.” This was pure, gun-to-noggin journalism. Remove something by end of business or else:

The Post story was extraordinary in its claims. It quoted Graham Brookie of the Atlantic Council, whose Digital Forensic Research Labs not only was taking part in Stanford’s dubious Election Integrity Project, but advised Facebook on some of the earliest “influence operations” removals in 2018, after the Senate recommended the platforms needed outside help. “In 2016, there were Macedonian teenagers interfering in the election by running a troll farm and writing salacious articles for money,” Brookie told the Post. “In this election, the troll farm is in Phoenix.”

The Post also referred to a Senate Intelligence Committee report on Russian trolls prepared by the firm New Knowledge — the same company whose CEO was outed after the publication of this Senate report in a scheme to tie fake Russian accounts to Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore — in asserting that in 2016, “the Kremlin-backed Internet Research Agency amplified Turning Point’s right-wing memes as part of Moscow’s sweeping interference aimed at boosting Trump.” New Knowledge cited “the use of Turning Point content as evidence of Russia’s ‘deep knowledge of American culture, media, and influencers.’”

Twitter didn’t appear to see anything like a Macedonian troll farm or a Russian internet attack brought home. In fact, they weren’t even sure suspensions were warranted. Kirk himself was not removed, nor was Turning Point sanctioned. Still, from the start, Twitter’s “US Gov Team” was copied on all communications involving Turning Point and Kirk:

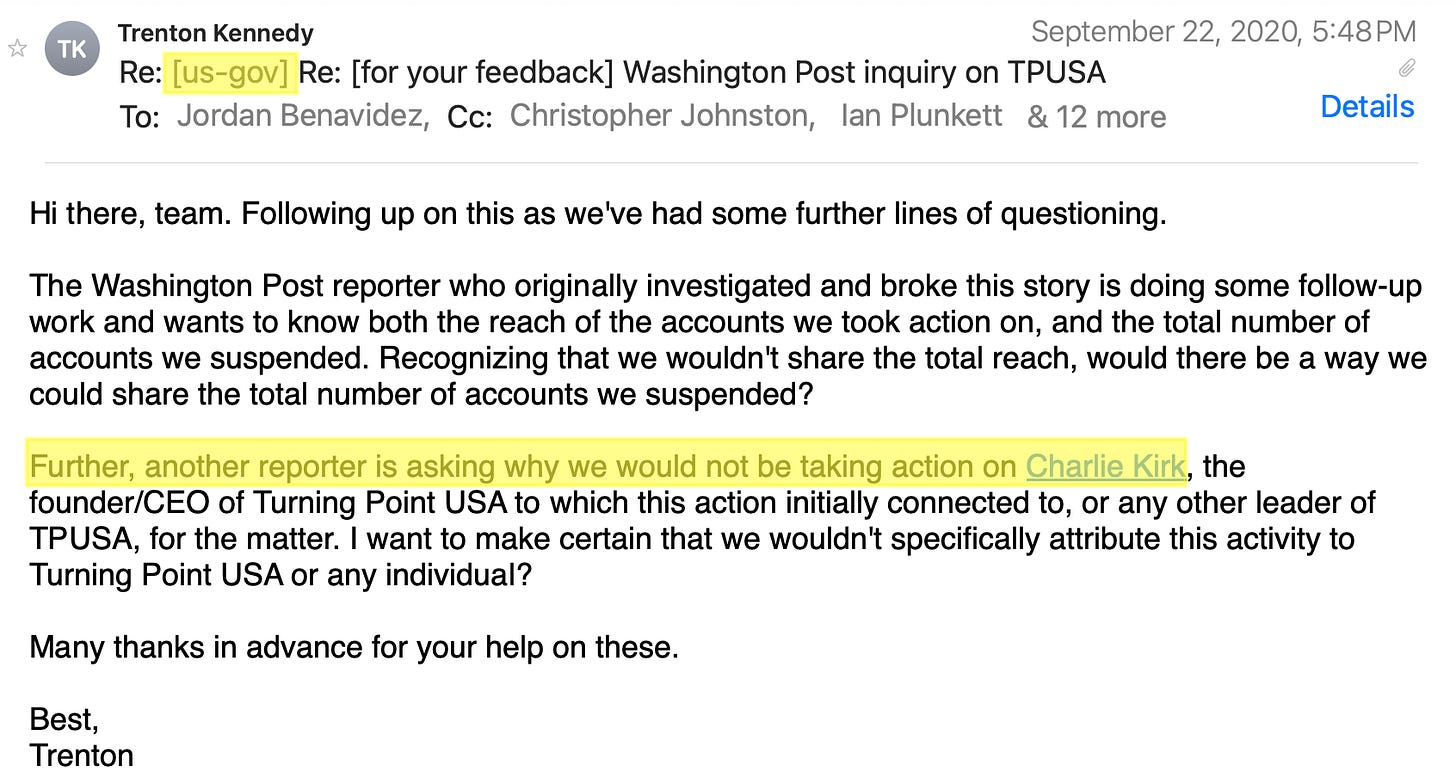

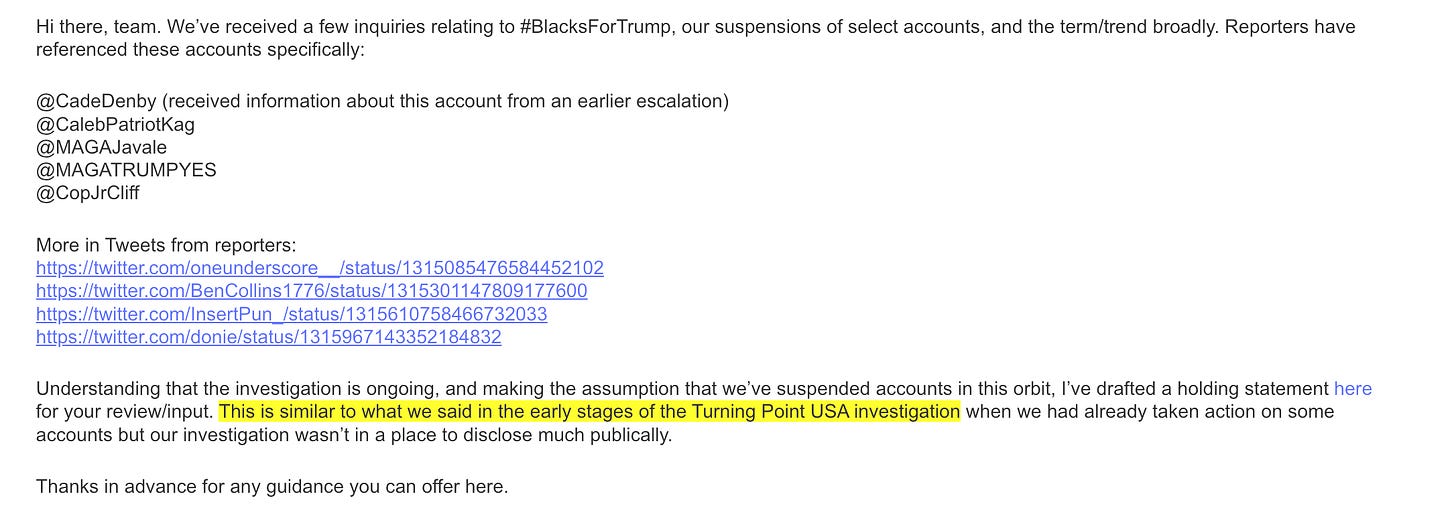

Even though the Post story was able to claim in the headline that its investigation prompted a “rebuke” by Twitter, not everyone was happy. Within two days, Twitter’s communications team asked the Trust and Safety analysts “why we would not be taking action on Charlie Kirk”:

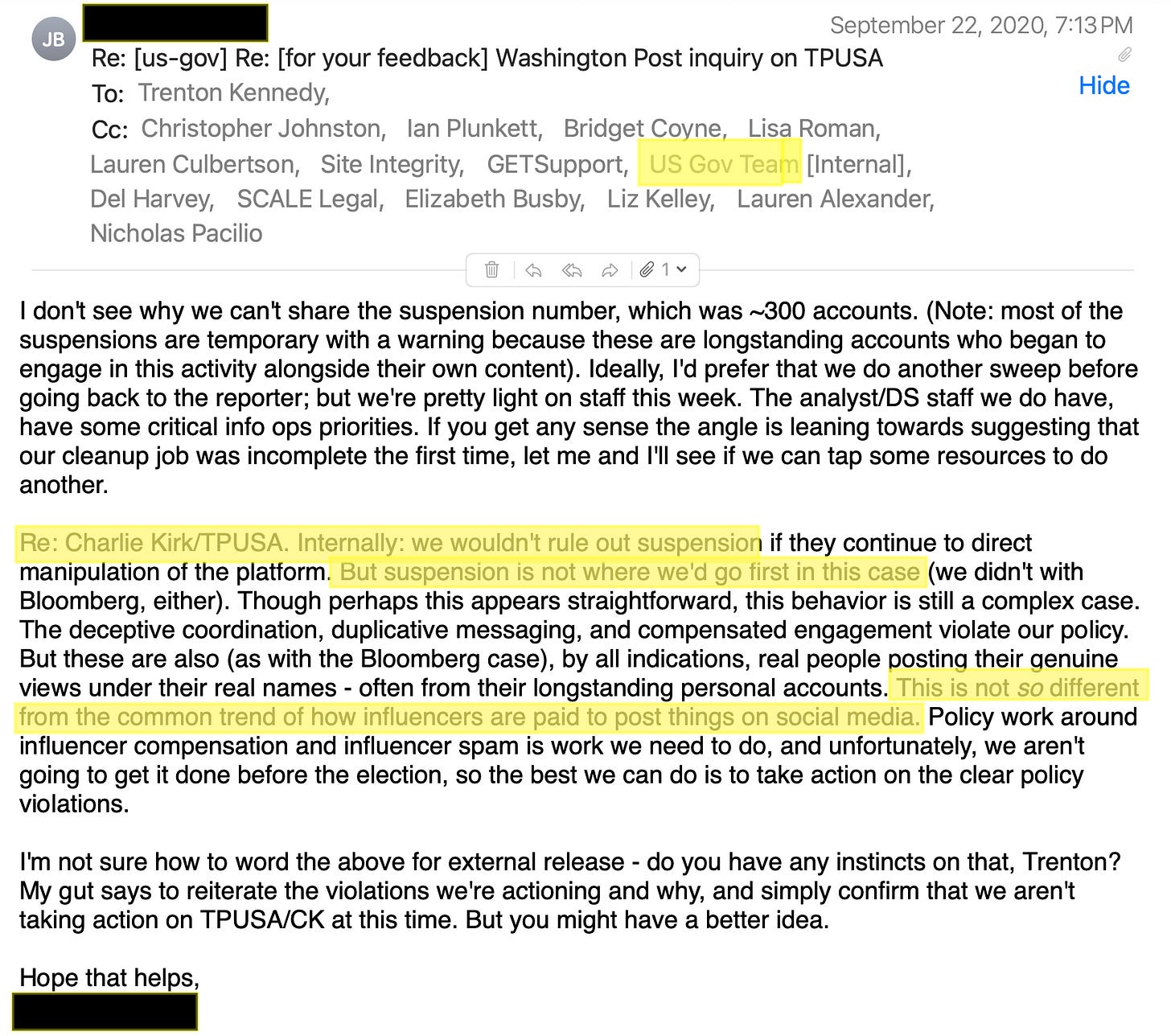

A few days later, a Twitter Trust and Safety reviewer complained about the pressure to suspend Kirk. Noting that the case involving Turning Point was similar to a copypasta violation from February in which the platform had sanctioned the campaign of Michael Bloomberg — not exactly a Macedonia or Russia-level horror — the analyst noted that “suspension is not where we’d go first” in this case, and “this is not so different from the common trend of how influencers are paid to post things”:

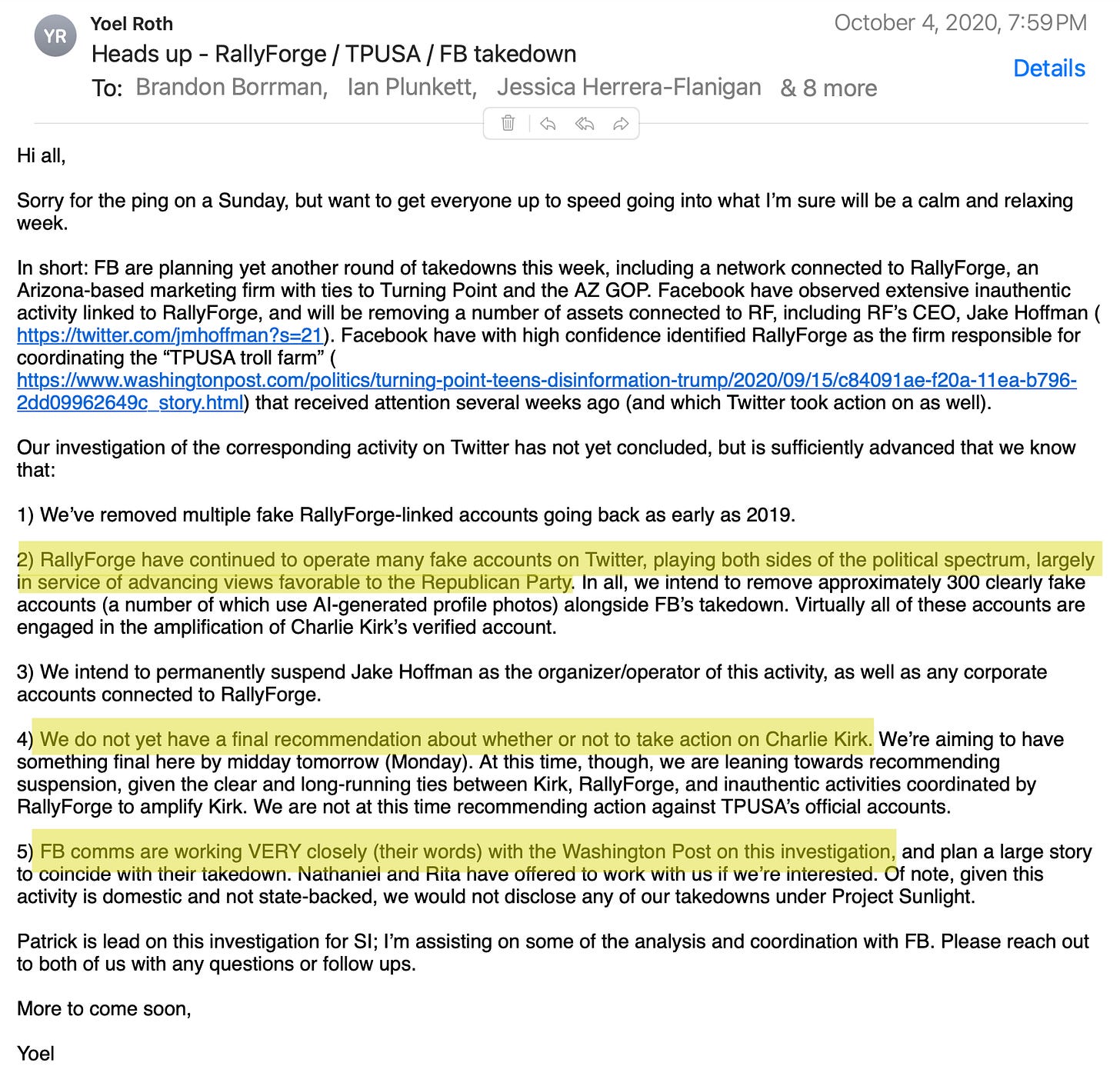

Nonetheless, by the end of September 2020, momentum was gathering toward a second story that was supposed to end with Kirk and Benny Johnson suspended. The key email comes from Trust and Safety chief Yoel Roth, who on October 4th says he’s “leaning” toward recommending suspension later that year.

“We do not yet have a final recommendation about whether or not to take action on Charlie Kirk,” he wrote on October 4, 2020. “We’re aiming to have something final here by midday tomorrow (Monday). At this time, though, we are leaning towards recommending suspension, given the clear and long-running ties between Kirk, Rally Forge, and inauthentic activities coordinated by Rally Forge to amplify Kirk.”

“Rally Forge have continued to operate many fake accounts on Twitter, playing both sides of the political spectrum, largely in service of advancing views favorable to the Republican Party,” Roth wrote.

Roth again explains that “[Facebook] comms are working VERY closely (their words) with the Washington Post on this investigation.” It’s also worth noting that one of Twitter’s CIA veterans, Patrick Conlon, was “lead on this investigation” for Twitter’s Site Integrity department.

By the next day, October 5th, 2020, Roth proposed action against Kirk, Rally Force CEO Jack Hoffman, and fellow influencer Benny Johnson. This decision came at a fraught moment for Twitter, just before the 2020 election. In fact, at that same time, they were also planning to release data about labeling of “election-related tweets” that would inspire complaints about bias.

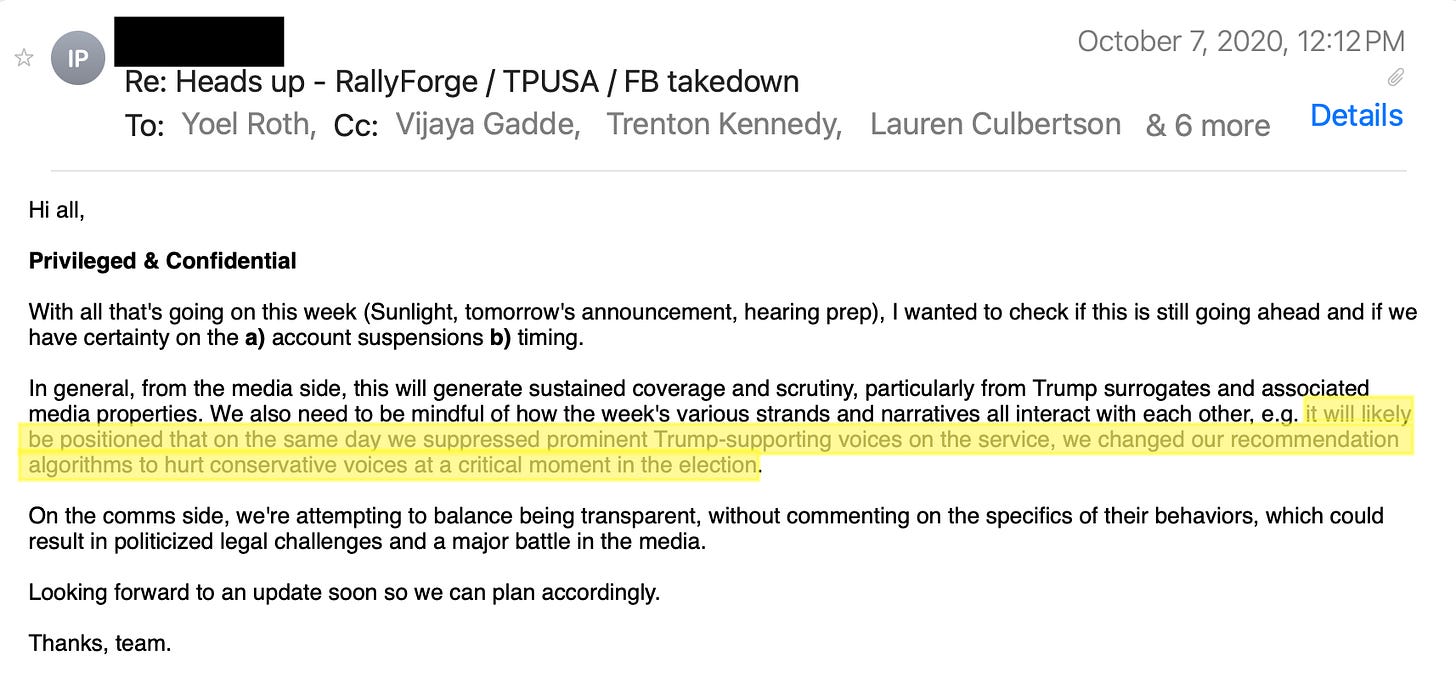

Doing both at the same time, one communications executive noted, might lead some to suspect “we changed our recommendation algorithms to hurt conservative voices at a critical moment in the election.” This, the executive speculated, could lead to “politicized legal challenges and a major battle in the media,” among other things:

We also need to be mindful of how the week’s various strands and narratives all interact with each other, e.g. it will likely be positioned that on the same day we suppressed prominent Trump-supporting voices on the service, we changed our recommendation algorithms to hurt conservative voices at a critical moment in the election..

The highest executives in the company, including Vijaya Gadde, agreed to a 5:30 ET meeting to discuss the question. By 10:58 p.m., word came down: Twitter decided not to suspend Kirk and Johnson, “pending further investigation of the strength of the ties between those accounts and the RallyForge network,” while it would remove Hoffman and 262 associated accounts. There is a notation about sending a “final warning” text to Hoffman and Johnson, but then just after one executive asks for a “comms review” of the warning letter, “we can expect that to be tweeted/made public.”

It’s not clear a warning text was ever sent. I asked Benny Johnson if he received a warning.

“No I did not,” he said last night.

The next day, comms official Trenton Kennedy sent a tweet to senior executives expressing satisfaction with the Washington Post, whose story claimed Rally Forge was “creating the appearance of a social media groundswell in support of Trump.” Quoting Facebook’s Nathaniel Gleicher, the piece said they used tactics “designed to evade the guardrails Silicon Valley put in place to limit disinformation of the sort Russia used during the 2016 presidential campaign.” It quoted the now-defunct Stanford Internet Observatory, which prepared a report on what it called an “astroturfing” operation, accusing the pro-Trump group of “secret coordination or unearned amplification.”

In a subsequent discussion Twitter execs noted the problem of not being able to ban an account that is merely deceptive politically or unclear. In vague terms they discussed the problem of not being able to directly connect people like Kirk to bad behavior, or the issue of how to categorize activity that might otherwise be common advertising: paying users to boost accounts. Facebook, in announcing its parallel decision, called for more “broad” legislation against “information operations, which would make life easier for the platforms, as it would be much easier to “action” behavior against the law.

Twitter execs admired the strategy. “Interesting twist on the whole thing. We couldn’t take more action because we need to be regulated first,” wrote Roth.

After being rebuffed twice that fall, Twitter finally relented and banned Kirk over a tweet in which he reportedly claimed, “Pennsylvania has just rejected 372,000 mail-in ballots.” That seemed to be the end of that episode, until a year later, when a Washington Post reporter claimed in a tweet Hoffman had resurfaced on the platform under a new name. Twitter lacked a “technical link” to the old account, but what’s interesting is one official said, “I’m holding off the reporter from writing but I have a feeling this might spark more digging on others included in our action from last fall.”

There are several major issues with the platforms’ behavior toward Kirk.

One is that while there are examples in the files of Twitter’s Trust and Safety department taking action against a Democrat-aligned group or individual engaged in “inauthentic activity,” there are also numerous examples of the company not doing so, the most conspicuous being the case involving alleged Russian bot-detecting dashboard Hamilton 68. “We have to be careful on how much we push back… publicly” then-Twitter-employee Emily Horne, once of the National Security Council, said about Hamilton 68, who just this summer had her security clearance pulled by Tulsi Gabbard.

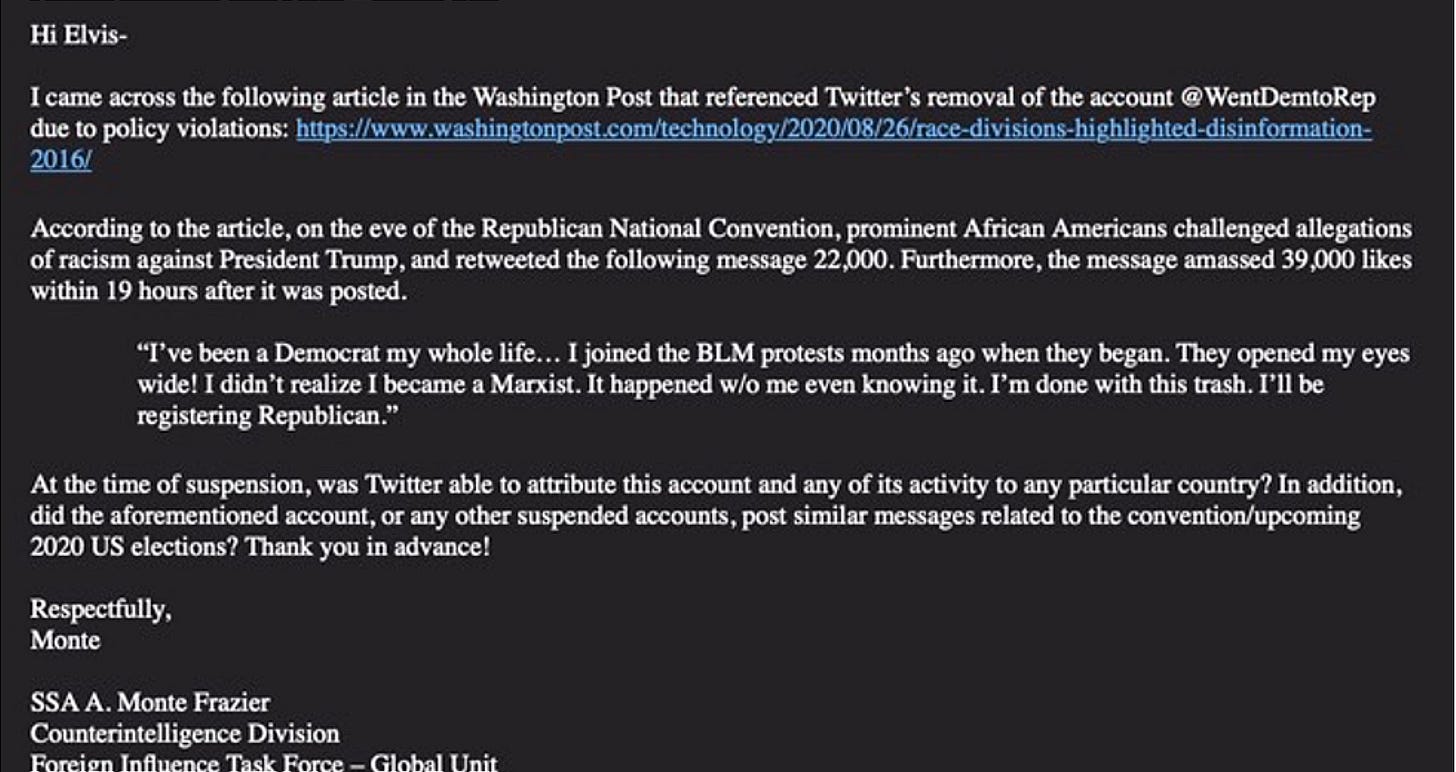

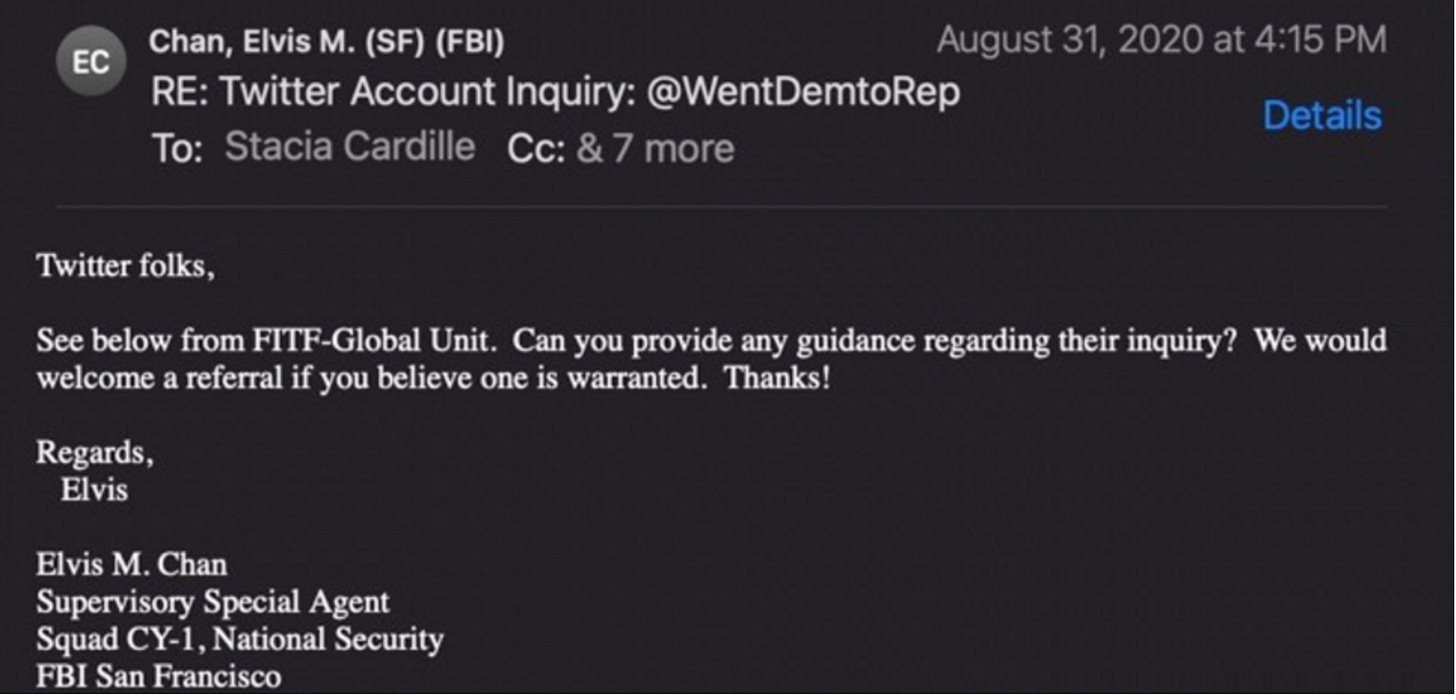

Perhaps more damning, when Twitter took action against Democratic-aligned accounts or discovered issues with the methodology of Democratic-aligned NGOs or research facilities, it frequently did not involve the press. Twitter’s Trust and Safety Department kept its frustration with the Clemson Media Forensics Hub to itself, for instance, to a degree that may even have had an impact on Kirk. Just before the first query about Kirk from Isaac Stanley-Becker in September 2020, the same Post reporter worked with Craig Timberg on a story about alleged fake accounts targeting black voters and the #WentDemtoRep campaign. The story cited Clemson research and so impressed an FBI Counterintelligence official that he wrote to San Francisco Field Office agent Elvis Chan, who in turn asked Twitter to look into the matter:

Chan wrote to his “Twitter Folks,” asking for help in looking into the matter:

When Twitter was deciding what to do about “WentDemToRep,” one exec recalled that it was similar to the first time they’d actioned Kirk: though they took action early, they often didn’t really have a lot of information until later. The early action was clearly done for the sake of the media:

Kirk was banned once, then finally actioned again, and again, with groups like the DFRLabs and New Knowledge working with the Washington Post and other outlets to advertise the action.

Efforts to remove Kirk aren’t urgent background to his assassination, but the episodes do play a part in the overall story. Unquestionably, antagonists of Kirk and Donald Trump recognized that he was an important Internet voice, and the repeated actions sent a signal that he needed to be removed — either for spreading “disinformation” or for more dubious claims of “inauthentic” activity. That there were repeated efforts to go after the same person before the 2020 election also speaks volumes. No other figure in Trump’s orbit had the kind of reach with young people and the same Internet savvy. Stanley-Becker hasn’t responded, and it’s doubtful he would or could answer, but it sure would be interesting to know what source proposed Turning Point and Rally Forge as targets for removal.

https://www.racket.news/p/twitter-files-the-muzzling-of-charlie