Bill Gates Says We’ll Survive Climate Change, World Furious

In the panic age, nothing offends like optimism.

From the “You can’t make this up” file:

Billionaire Bill Gates yesterday gave an interview on CNBC and released an essay called “Three Tough Truths About Climate.” One of the “tough truths” was — this is not a joke — “Climate change is a serious problem, but it will not be the end of civilization.” Gates put his “truth” in a box under a field, probably the most humorously grasping use of green imagery since the UNorth commercial in Michael Clayton.

Why survival should be “tough” news wasn’t clarified, but Gates offered a summary of his thesis:

There’s a doomsday view of climate change that goes like this:

In a few decades, cataclysmic climate change will decimate civilization. The evidence is all around us—just look at all the heat waves and storms caused by rising global temperatures. Nothing matters more than limiting the rise in temperature.

Fortunately for all of us, this view is wrong. Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further.

Reaction was swift and furious. In the words of the immortal Greta Thunberg, “HOW DARE YOU!” The New York Times rushed a piece out titled, “Bill Gates Says Climate Change ‘Will Not Lead To Humanity’s Demise.’” The paper linked to Gates’s net worth on the Bloomberg Billionaires’ Index, to his prior comments about irreversible ecological damage, and to the Gates Foundation’s $1.4 billion commitment to climate change research. It didn’t link to Gates’s new essay, though, instead quoting the editor of Inside Philanthropy, who said “one could imagine” this was Gates’s way of “not wanting to be a target of the Trump administration.” Social media is still burning with theories about Gates betraying the climate cause to get out from under an investigation into his foundation’s alleged funding of Chinese entities. The imminent extinction dream is dying hard.

On the eve of the the COP30 climate summit in Brazil, Gates’s downshift from “We’re gonna die!” to “A serious but survivable problem” was ripped as a grievous affront. The climate story has been reported as an extinction panic for decades, in the process becoming one of the most influential news stories ever. Its impact reached far beyond energy policy to realms like mental health, family planning, even journalism and academic freedom. Ostensible uniformity of climate consensus was used as an argument against both “viewpoint diversity” on campuses and objective “both sides” reporting.

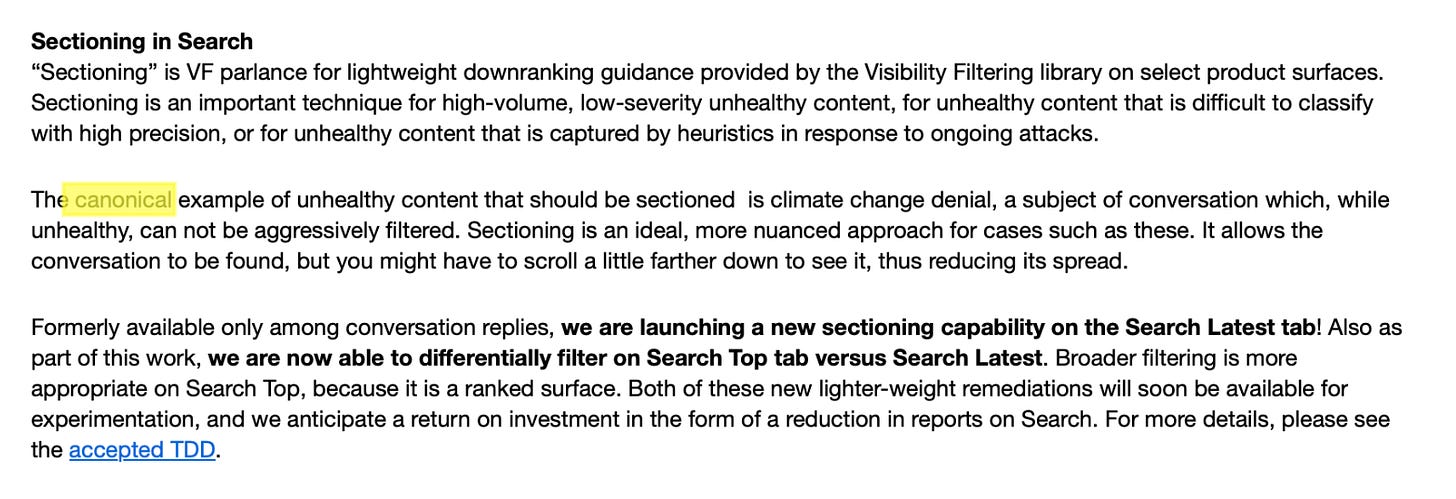

Global warming and the certainty of a “sixth mass extinction” became this century’s End-Times religion, replete with the Millerite pattern of repeat “final” warnings and failed predictions or “tipping points” (we reportedly just passed one two weeks ago, missing a chance to prevent “widespread dieback”). Even when warnings were scientifically accurate, the concept of unsurvivable catastrophe was still treated as an article of faith, and refusal to panic could be a cancelable offense. Denial of climate emergency was even listed in Twitter’s Files as the company’s “canonical” (!) example of “unhealthy content,” i.e. speech that should be shadow-banned even if it doesn’t violate rules:

Now one of the most influential figures in the fight against global warming, a man who just a few years ago wrote a book called How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, essentially just mumbled “never mind,” in a memo that reads like an admission of strategic overreach.

“To use the British expression, they over-egged the custard,” says Professor Steven Koonin, former Undersecretary for Science in Barack Obama’s Department of Energy and author of Unsettled.

Just when you thought the world had exhausted the reasons for hating Gates, people on all sides of the climate issue are seething. The Microsoft titan will go down in history as God’s own proof that no amount of money can buy likeability:

Scientist James Hansen’s testimony to Congress in 1988 is generally credited as the beginning of climate change as a popular news phenomenon, but voices ranging from Al Gore to Bill McKibben to Stephen Hawking have been sounding alarms ever since. As Gore described it, global warming was a “planetary emergency” that was “beyond politics.” I remember reading the environmentalist McKibben’s pucker-inducing book The End of Nature, in which he warned readers not to think of slow, “geologic” time anymore, but to realize “we have already stepped over the threshold” of irreversible change, being “at the end of nature” already.

Man, I remember thinking, that’s harsh. There was no reason to doubt it, especially since my work at the time had led me on a tour of some of the world’s grimmest ecological disasters (seeing the vanished Aral Sea in person was a reality check). Still, my generation’s cautionary horror tale was nuclear war, not warming, so I never had the experience of growing up saturated in apocalyptic climate messaging. Members of the next generations weren’t so lucky, served those scare stories constantly, almost as a prophylactic against relaxation and happiness. It worked. By October of last year, an astonished 62.9% of people between the ages of 16 and 25 agreed with the statement, “Humanity is doomed.” Over half of respondents, 52%, agreed with the statement, “I’m hesitant to have children.”

Climate fear soared in 2018, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a report warning of “severe consequences” for humanity if action was not taken to keep temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030 (this is the “tipping point” we reportedly failed to avoid two weeks ago). This birthed the “We have 12 years to act” catch-phrase, which in turn birthed even darker predictions and led to the elevation of the aforementioned Swedish super-celebrity Thunberg, who earned repeat Nobel Peace Prize nominations for scaring the crap out of me via a speech demanding, “How dare you watch your Patriots game! You have stolen my childhood!”

https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/TMrtLsQbaok?rel=0&autoplay=0&showinfo=0&enablejsapi=0

The impact climate messaging (or education, if you prefer) had on Thunberg’s generation was described in a strange way. Harvard researchers in 2023 wrote semi-approvingly about “climate anxiety,” with one adolescent psychiatrist explaining that while some see generalized anxiety as a “pathological response that needs to be treated,” climate anxiety was different: “A healthy response to a real threat.” Other academics agreed that youths feeling a “chronic fear of environmental doom” and experiencing “panic attacks, loss of appetite, irritability, weakness and sleeplessness” were behaving more healthily than those who turned away “in denial or disavowal.” Climate anxiety was not pathological but “adaptive,” according to Cambridge researchers. No one thought the idea of a society that believes in “adaptive anxiety” was odd.

Some celebrated the success older generations had in freaking out the world’s youth, with people like Thunberg celebrated for expressing feelings of “intergenerational injustice,” having been “invalidated, betrayed, and abandoned” by old-heads who failed to fix the planet. This always seemed strange. Again, even if warnings were accurate, why foster anxiety on purpose? Would we teach young people to embrace being panicked and irritable before sending them to deal with war, pestilence, invading aliens, or any other serious challenge? If older voices were wrong to instill these fears they were doing terrible psychological damage, but even if warnings were right they were prematurely signaling failure, weakening the country through a campaign that was like the opposite of “Nothing to fear but fear itself.” We split the atom on a clock and went to the moon, but can’t fix this? What’s been the utility in thinking this way?

These constant invocations of disaster haven’t even had their intended effect. CNN poll guru Harry Enten went on air this summer to complain that it “boggles the mind” that Americans aren’t more “afraid of climate change,” given “everything that we see on our television screens… the hurricanes, the tornadoes, the flooding”:

Enten’s boggled mind offered a hint into why the “doomsday” approach might have failed. In Unsettled, Koonin wrote about a “disconnect” that’s produced in “the long game of telephone that starts with the research literature and runs through the assessment reports to the summaries of the assessment reports and on to the media coverage.” An example of such telephone “disconnect” is simple confusion of weather and climate, a constant feature of coverage. Should the public be worried about climate change because they see pictures of storms, tornadoes, and floods on CNN? Many political figures and scientists (like “Science Guy” Bill Nye) say yes. Joe Biden traveled to my home state of New Jersey in 2021 and declared a “code red” warning, saying Hurricane Ida was evidence of an “existential threat” of climate change.

Other scientists however contest claims of worsening weather data, while still others (like Koonin) insist individual weather events aren’t as important, and the crucial issue is their frequency over time. Around the same time Biden was declaring his existential code red, bodies like the American Meterological Society were declaring a slight decrease in the quantity of hurricanes over time, echoing findings by a number of other bodies (even the Washington Post in 2015 ran a story saying, “Global Warming Fueling Fewer But Stronger Hurricanes”). The climate consensus constantly referred to seems to involve most scientists agreeing that the earth is warming and agreeing this is due (or “very likely” or “extremely likely” due, according to a common caveat) to human activity. There are controversies about almost everything else, though, many of which the public never hears about because of algorithmic suppression and other factors.

There are few headlines telling the public people NASA satellite imagery shows the earth has actually gotten greener over the last 100 years. The celebrated late physicist Freeman Dyson, known to Star Trek fans as the creator of the “Dyson Sphere” idea featured in a Next Generation edisode, told an interviewer at Princeton that this was caused by carbon dioxide, leading to an increased food supply, as one would expect in any greenhouse. Obviously, not everyone agrees with him, but the intense media emphasis on drowning out such alternative views seems to have contributed to a public that has been freaked out, but not always well-informed, being hyper-focused on only certain facts:

I’m not at all saying climate change isn’t a problem, just that reinventing coverage to downplay alternative theories or ambiguous data to facilitate the amping of social concern (read: fear) has been a disaster, one that Gates played a huge role in creating. It’s helped create a population that tends to catastrophize everything, not just news about the environment.

Because the press in the last century hyped everything from “Africanized bees” to Dungeons and Dragons as civilization-imperiling threats, young reporters were once warned against over-selling fear. That ended with climate coverage, one of the first stories to fit seamlessly with the new dynamics of digital media. Being both terrifying and “not debatable,” as Gore put it, global warming was a prototypical early fixation in the Manichean hellscape of doom-scrolling zealotry that quickly came to characterize 21st century thought.

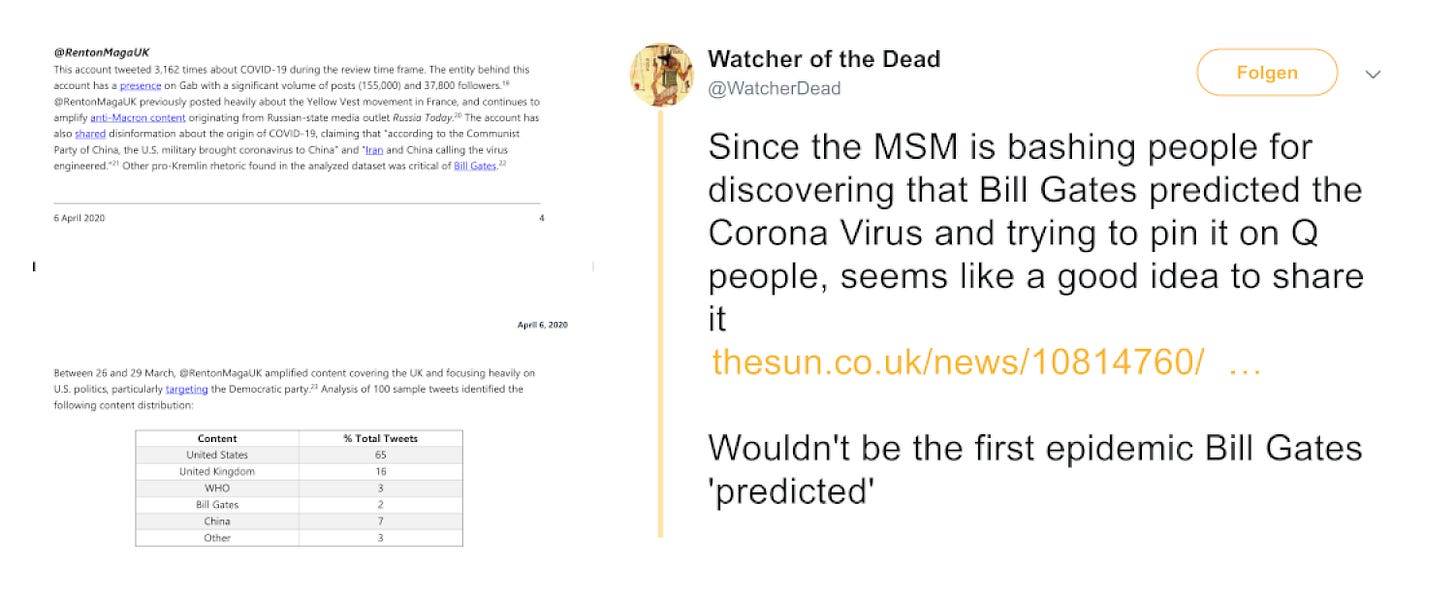

PR campaigns to spread climate awareness stressed that mere reporting wasn’t enough to effect change. Shaming campaigns were employed (“climate denialism” eventually became a mark of shame on the order of Holocaust denialism), and some of the earliest efforts to enlist Internet platforms to “moderate” controversial speech involved climate discussions. Along with suppression, algorithms were created to amplify and/or defend certain voices in the movement, especially Gates himself, whom companies like Blackbird.AI described as victims of “conspiratorial” hashtags like #gates and #WEF. The now-defunct Global Engagement Center devoted State Department resources to warnings about pretty damn small accounts that criticized Gates:

Instead of finding ways to stimulate discussion, the climate “debate” over time became framed as anti-discussion, where hunting “denial” became as important as awareness. This became the template for coverage of a range of other social-emergency stories, from Covid to the 2020 racism health crisis to last year’s “end of democracy” election. These and other “doomsday” stories all had one thing in common: people became so used to having their “adaptive” anxieties stoked via maximalist scare headlines that they became genuinely unreceptive to suggestions that life might not be so bad.

In the last day and a half, for instance, most papers rejected the Gates claim that “we’ve made great progress” and that climate change “will not lead to humanity’s demise.” The Guardian fumed that this was “at odds” with the pronouncements of UN Secretary General António Guterres, who said it was instead time to “recognize our failure” with regard to the climate crisis. The New York Times, while conceding there’s “some truth” to the Gates pronouncements, because “even the most dire forecasts don’t predict that rising temperatures will mean the end of civilization anytime soon” — a startling passage on its own — still insisted the billionaire’s decision to focus on other poverty issues fed into rhetoric “usually propagated by climate skeptics” that “pits efforts to tackle climate change against foreign aid for the poor.” I could not find a single mainstream report that suggested any of the optimism in the memo should be taken seriously.

This is similar to how audiences reacted throughout Covid to studies suggesting mortality rates were lower than initially reported, or that natural immunity was effective, or that healthy children had a low risk of death, or other encouraging news. We even saw this phenomenon with Russiagate, when news outlets had to brace audiences to be “disappointed” that Donald Trump might not turn out to be a Russian agent. Panic über alles!

Creating a population that wants to stay in a constant state of “adaptive” terror, to the point where it can’t tell the difference between a fixable problem and the end of the world seems to have been a conscious aim of decades of Gates-ian propaganda. Has it worked? Have “anti-disinformation” programs designed to prevent people from seeing the “canonical” sin of denialism increased public concern? Polls show they haven’t. It’s infurating that it will probably take a comment from Gates himself to make it socially acceptable for people to pull back from the ledge.

“Climate ain’t nothing,” says Koonin, “but it ain’t everything.”

https://www.racket.news/p/bill-gates-says-well-survive-climate