The Mysterious Disappearance of Amelia Earhart

Americans love a mystery, especially when it involves famous figures, and even more so when it involves the disappearance of those figures. When I was a young kid, I often heard that race of people called adults discuss the disappearance of internationally famous aviator Amelia Earhart in 1937 and, to a lesser degree, that of New York Supreme Court Judge Joseph Crater in 1930. Earhart and Crater were popular topics of conversation, their disappearances subject to much conjecture and controversy.

The disappearance of Judge Crater has faded from the American memory, but that of the most famous of our women aviation pioneers gets a jolt of new interest every decade or so because of an alleged artifact from her or her plane being found on one or another remote island in the Pacific. Most recently, a team of researchers from Purdue University say a satellite image of an object resting on the bottom of a lagoon in Nikumaroro is the Lockheed Electra flown by Earhart.

Born in 1897 in Kansas, Amelia Earhart was 23 in December 1920 when her father took her to an airshow in Long Beach, California. Captivated by the barnstormers performing their daring stunts, she declared she just had to go up in an airplane. The next day, her father paid Frank Hawks, a World War I pilot and stunt flyer, five dollars to take her up from Rogers Field on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. “By the time I got two or three hundred feet off the ground,” said Earhart, “I knew I had to fly.”

She was soon taking flying lessons on weekends from red-haired Mary “Neta” Snook, a fiery gal of Irish descent only a year older than Earhart. The two connected immediately. During the week, Earhart worked for a Los Angeles telephone company. “The family barely saw me,” said Earhart.

She soon bought a well-used biplane and flew the old crate whenever she could. She received her pilot’s license in May 1923 from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. The United States did not start issuing pilot’s licenses until 1927.

In 1924, Earhart’s parents divorced, and her funds for flying were quickly exhausted. She sold her plane and took a series of jobs, eventually becoming a sales rep for an aircraft company near Boston. She was able to rent planes and fly fairly regularly. She joined the Boston chapter of the American Aeronautical Society and would be elected its vice president. She wrote newspaper columns about flying and promoted the founding of an organization of women pilots. In New England, she was becoming a well-known woman aviator.

George Palmer Putnam of G. P. Putnam’s Sons, who had published Charles Lindbergh’s phenomenally successful autobiography, was part of a small group of aviation enthusiasts who decided to sponsor a transatlantic flight with a woman aboard. He was told Amelia Earhart would be a good choice, and he found her ideal. She even looked like Lindbergh—tall, rail thin, and fine-featured, with blondish-brown hair and blue-gray eyes. She could have been Lindbergh’s sister. Putnam would publicize her as “Lady Lindy.”

Much to her disappointment, Earhart soon learned she would go as a passenger, not a pilot. With Wilmer Stultz, a veteran of both the U.S. Army and Navy, as pilot and Louis Gordon as co-pilot, the flight took off from Newfoundland on the morning of June 17, 1928. Twenty-one hours later, Stultz landed the pontoon-equipped plane in a bay in Wales. Though Stultz was at the controls for the entire flight, he and co-pilot Gordon played second fiddle to passenger Amelia Earhart in the celebrations in Britain immediately afterward. That a woman had dared to make the dangerous flight across the Atlantic fired the public’s imagination.

Back home, the three of them received a ticker-tape parade in New York City and met President Coolidge in the White House. Stultz and Gordon quickly faded from the limelight. Stultz died in a plane crash in 1929. Gordon worked for TWA for more than 20 years and died in relative obscurity in 1964.

Meanwhile, Earhart’s fame grew. Putnam had her write a book about the flight and arranged a lecture tour for her. Various companies asked her to endorse their products. Sponsors came forward to finance her flights. She became the first woman to fly solo from coast to coast, and the first woman to solo the Atlantic. She flew solo from Hawaii to California; from Los Angeles to Mexico City; and from Mexico City to New York.

In 1931, she married Putnam. A few have argued that he used her as a money-making tool, pushing her in her career relentlessly, but those close to the couple knew Amelia as a strong-willed and independent woman who did only and exactly what she pleased.

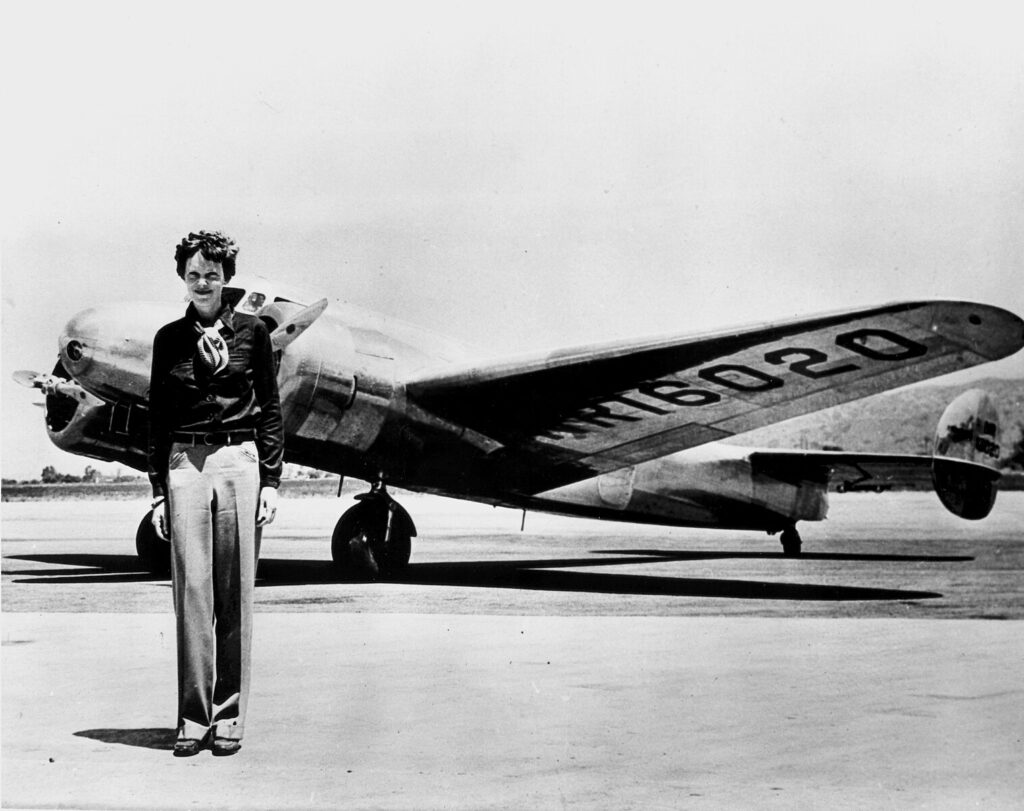

Late in 1935, the two began thinking about a plan for her to circumnavigate the globe. The choice of plane was a consequence of Earhart spending some of her time in 1935 and ’36 as a visiting professor in Purdue University’s Department of Aeronautics. The university donated the princely sum of $50,000 to have Lockheed build her an Electra 10E.

Earhart wouldn’t make this flight solo but would be accompanied by a navigator, Fred Noonan, renowned in both dead reckoning and celestial navigation. Noonan had established Pan Am’s routes across the Pacific, including those for the famous China Clipper, and had trained Pan Am’s navigators. Physically, he was a male version of Amelia, tall, lean, fine-featured, and blue-eyed, but with auburn hair.

Born in Chicago in 1893 to parents of Irish descent, Noonan lost his mother when he was four and was sent to live with relatives. He ran away to Seattle at age 12, and by 17, he was serving as a Merchant Marine. During World War I, three of the ships he sailed on were sunk by German U-boats. By his mid-20s, he was serving as a navigation officer. He was only 32 when he received his Master’s license to skipper ships “of any gross tonnage … in any ocean.”

While still serving in the Merchant Marines, Noonan learned to fly. By 1930, he had a commercial pilot’s license. He switched careers and was hired by Pan Am. After working out of Miami and Port-au-Prince, Haiti, he was transferred to San Francisco early in 1935 to chart routes across the Pacific. After having flown the Pacific more than two dozen times, he left Pan Am at the end of 1936, thinking of starting his own navigation school.

There have been writers who have made much of Noonan’s drinking. He was known to drink—occasionally heavily—but never on the job. Pan Am’s Chief Pilot, Ed Musick, who was the captain on Pan Am’s first flights across the Pacific, insisted on having Fred Noonan aboard as his navigator.

On St. Patrick’s Day 1937, Earhart’s round-the-world flight began from Oakland. Noonan wore a shamrock on his lapel. Flying the Lockheed Electra on takeoff was Paul Mantz, a Hollywood stunt pilot, who had been giving Earhart instruction on the Electra. He thought she wasn’t ready to handle a takeoff with a thousand-gallon load of fuel, which put the total weight of the Electra above the recommended limit.

Also on board was German-born Harry Manning, a radio communications specialist and navigator, as well as the skipper of a merchant ship and a licensed pilot. It was thought Mantz would remain aboard until Hawaii, and Manning would stay until the flight had crossed the Pacific.

The Electra arrived at Honolulu without incident. The next leg of the flight would be a 1,900-mile hop southwest to Howland Island. On March 20, with Mantz watching from the side of the runway, Earhart began the takeoff roll. Overweight again, the Electra began a slight fishtail. It got worse as the plane accelerated. This caused a tire to blow, a landing gear to collapse, and the plane to ground loop. Publicly, the crash was blamed on the tire blowing. Privately, Mantz said Earhart failed to keep the Electra headed straight down the runway and the increasing fishtailing put undue force on the tire, causing it to blow.

No one was hurt, but the plane was badly damaged and had to be shipped to the Lockheed plant in Burbank for repairs. Once back in California, Manning publicly stated he had to get back to duty with his shipping line. Privately, he said, “I had no faith in her ability as a pilot.”

Because of changing global weather patterns, it was decided the second attempt at circumnavigating the world would be West-East. With no fanfare, Earhart, Noonan, and the plane’s mechanic, Bo McKneely, flew from California to Florida, making two stops along the way.

Early on the morning of June 1, 1937, Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan took off from Miami. Now, radio stations and newspapers began daily reporting on the flight. The Electra made several stops before finally arriving at Natal, Brazil.

Earhart and Noonan now faced a 1,900-mile crossing to Dakar, Senegal. They ran into storms during the crossing and Earhart had trouble maintaining the dead-reckoning course set by Noonan. It shouldn’t have mattered greatly, though, because Noonan was using the “deliberate error method” of navigation, a way to compensate for small errors that are magnified over long distances.

Though only an approximation, pilots use the “1 in 60” rule. If a pilot is aiming for a target 60 miles away but is off his heading by 1 degree, and assuming no en route corrections, he will reach his target 1 mile off dead center. Now think of aiming for a target, such as Dakar, 1,900 miles away. One degree off the heading would put the pilot a bit more than 30 miles off the target.

Using the deliberate error method, Noonan didn’t aim precisely for Dakar but for a point well north of the city. That way, they would know which way to turn when they reached the coast—in this case, to the right (south)—to find Dakar. Instead, for some reason, Earhart chose to turn left. She followed the coast north for 100 miles or more before coming upon an airstrip at St. Louis, Senegal. The Electra was low on fuel by then. The next day, they flew 160 miles down the coast to Dakar, where they were wined and dined by French officials.

From Dakar, it was across the southern edge of the Sahara Desert to the Sudan, with stops along the way at remote and obscure spots known to few beyond Foreign Legionnaires. After a couple of relatively short hops, they took off from the Horn of Africa and flew to Karachi, India. It was now June 16, and they were halfway around the world. They then stopped in Burma, Siam, Malaysia, and the Dutch East Indies before arriving at Darwin, Australia.

After repairs to the Electra’s radio equipment, they took off from Darwin on the morning of June 29, landing seven hours later at Lae, New Guinea. By then, they had flown 22,000 miles.

On July 2, 1937, with all tanks topped off, holding a total of 1,100 gallons of gas, Earhart barely got the Electra off the end of the runway. All Earhart and Noonan had to do now was fly some 2,600 miles to Howland Island, only a mile and a half long and a half-mile wide. Making finding that speck of land even more difficult were the charts of the time, including those Noonan was using, which had the island nearly six miles from its actual location.

Noonan determined the course they would fly by dead reckoning, knowing he could adjust it with position fixes determined from celestial navigation. Noonan had wanted to use the deliberate error method and aim for a point between Howland and Baker, another small atoll, 43 miles south of Howland. That way, when they arrived somewhere between the two islands, they would know to turn left and fly north to Howland. Earhart rejected the idea, perhaps because a U.S. Coast Guard cutter, Itasca, would be circling the waters immediately to the west of Howland, waiting for their arrival. At that point, radio direction finding (RDF) could be used.

Both the Electra and Itasca had RDF capability. In photos of the Electra, an RDF circular antenna is visible atop the cockpit. RDF was first adopted in aviation in 1936. A land-based station or a ship could transmit a signal on a particular frequency, and a pilot could set a receiver on that frequency and then rotate the antenna any number of degrees and listen for a stronger signal. When the antenna was rotated to the point of the strongest signal, it would give the pilot a bearing to fly.

In addition to Itasca, there were the tug USS Ontario, stationed about halfway between Lae and Howland, and the seaplane tender USS Swan, cruising between Howland and Hawaii. These Navy vessels were also RDF-equipped.

Despite winds that were either head-on or quartering, at the halfway point, reports from Ontario and from the island of Nauru had the Electra right on course. Earhart’s flying and Noonan’s navigating were impeccable. However, the Electra now faced much stronger winds and more cloud cover and squalls. By now, it was dark, and only when there were breaks in the cloud cover could Noonan use his sextant to shoot the stars and fix their position. Most researchers argue that the strong winds during the second half of the flight pushed the Electra slightly off course to the north.

Itasca first heard from Earhart at 5:12 a.m. Howland Island time, when she asked for a bearing, saying she would stay on the air and whistle into her mic until Itasca got a fix on the Electra. However, Itasca didn’t again hear from Earhart until 6:15 a.m., when she said she was about 200 miles out and would again whistle into the mic. But Itasca’s radio operators heard nothing until 6:46 a.m., when Earhart said, “Please take bearing on us and report in half an hour. I will make noise in the microphone. About 100 miles out.”

At 7:42 a.m., Itasca heard Earhart again. “KHAQQ [the Electra’s call sign] calling Itasca. We must be on you, but cannot see you. But gas is running low. Been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.”

“Now she’s blown my head off,” Itasca radioman Tommy O’Hare later said. “I have her at a signal strength of five, which means she is overhead coming on us, and I physically put my head out the radio room door and looked in the sky for her.”

Earhart was back at 7:58 a.m. “We are circling but cannot hear you. Go ahead on [radio frequency] 7500, either now or on the schedule time on half hour.” At 8:04 a.m., “KHAQQ calling Itasca. We received your signals but unable to get a minimum [meaning a bearing]. Please take bearing on us and answer 3105 [a different frequency, which Earhart hoped would give better reception] with voice.”

At 8:44 a.m., again with a signal strength of 5, came Earhart’s last transmission—at least the last one heard, “We are on line 157-337. Will repeat this message. Will repeat this message on 6210 KCS [kilocycles per second]. Wait.” About a minute later, “Listening on 6210 KCS. We are running on line north and south.”

The line 157-337 referred to degree headings on a compass. This is a line of position (LOP) and Noonan would have determined they were on it—Howland’s LOP at that time of day on that date—by shooting the sun with his sextant and then referring to an almanac with tables denoting when and where a thing is supposed to be. If it had been night, he could have shot two or more stars and not only determined they were on the 157-337 LOP but exactly where on that line they were relative to Howland.

This meant Earhart had to fly southeast and northwest along the LOP to find Howland. The island was not only difficult to spot because it was small and low lying, but also because there was intermittent cloud cover and an occasional squall line. Most likely, Earhart was flying on the LOP northwest of Howland and never near enough to spot it. She probably soon ran out of gas and ditched in the sea.

In a less likely case, if the Electra had been on the LOP to the southeast of Howland, Earhart and Noonan would have flown over Baker Island—on the LOP 43, miles from Howland—which would have told them to turn about and fly northwest to Howland. If they had not spotted Baker and had continued flying southeast, the next island on the LOP was Gardner, some 350 miles beyond Baker.

About an hour after Earhart’s last known transmission, Itasca initiated a search. Alerted by Itasca, Ontario and Swan were quickly steaming toward the search area. Other ships of the U.S. Navy were soon involved. Planes began circling the area. The search continued for 16 days. Nothing was found, no plane, no flotsam, no Amelia Earhart or Fred Noonan.

It wasn’t long before the rumor circulated that Earhart and Noonan had been on a spying mission for President Roosevelt and, while reconnoitering a Japanese-occupied island, had been forced down. They were then interrogated and tortured, and eventually executed. This scenario became the plot for Flight for Freedom, a 1943 film starring Rosalind Russell and Fred MacMurray, although Russell’s character was called Tonie Carter, and it contained the standard disclaimer that the movie was a work of fiction.

The spy mission theory gained more popularity after Marines and soldiers secured Saipan. More than a dozen Chamorros, the native people of Saipan, came forward telling stories of a crash landing during July 1937 and a woman and a man being taken into custody by Japanese soldiers. The Chamorro descriptions of the couple sounded like a match for Earhart and Noonan. Several articles and books have argued the spy mission theory.

Of the many theories about the mysterious disappearance of the flyers, the most bizarre argues that Amelia Earhart reached a small island and, in disguise, eventually made her way back to the United States, living out her life in quiet seclusion.

The mysterious disappearance of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan is something of an industry. There are not only hundreds of individuals devoted to researching the disappearance but also several organizations. Every time a shoe or a fragment of an airplane or some such artifact is discovered on an uninhabited island in the South Pacific, it is promoted as possibly, or even probably, from Earhart or the Lockheed Electra. I suppose we all hope there’s something more to the disappearance than that Earhart ran out of gas, ditched, and the Electra sank.

As of this writing, a team of researchers from Purdue University, Purdue Research Foundation, and the Archaeological Legacy Institute is preparing for a formal expedition to Gardner Island in the Western Pacific, now known as Nikumaroro. Most of the participants will be flying from Amelia Earhart Terminal at Purdue University Airport. They will rendezvous with other participants at Majuro, the air hub for the Marshall Islands.

From Majuro, a ship will then take the researchers some 1,400 miles to Nikumaroro, where they hope to find Earhart’s Electra, the one paid for by Purdue University in 1936. Like surfers who study satellite imaging to identify possible good breaks in remote, unspoiled locations, Amelia aficionados study the imaging for objects that could be sunken planes in the general area of Earhart’s disappearance. One such object in Nikumaroro’s lagoon not only looks promising, but the same object is visible in an aerial photo of the lagoon taken in 1938.

If the object is the Electra, it would be one of the greatest discoveries of aviation history. However, it doesn’t seem possible that the plane had enough fuel remaining to fly all the way to Gardner Island. Nevertheless, the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), a highly respected organization, has published an article arguing that Earhart and Noonan reached Gardner and landed on an exposed reef. The theory has Noonan dying in the landing and Earhart shortly afterward, with the plane soon slipping off the reef and sinking to the bottom of the lagoon.

Whether or not the Purdue University expedition finds the Electra, the investigation into the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, an American heroine, remains high adventure.

https://chroniclesmagazine.org/columns/the-mysterious-disappearance-of-amelia-earhart