How the Covid Inquiry Protected the UK Establishment

After four years, hundreds of witnesses, and nearly £200 million in costs, the UK Covid Inquiry has reached the one conclusion many expected: a carefully footnoted act of self-exoneration. It assiduously avoids asking the only question that truly matters: were lockdowns ever justified, did they even work, and at what overall cost to society?

The Inquiry outlines failure in the abstract but never in the human. It catalogues errors, weak decision-making structures, muddled communications, and damaged trust, but only permits examination of those failings that do not disturb the central orthodoxy.

It repeats the familiar refrain of “Too little, too late,” yet anyone paying attention knows the opposite was true. It was too much, too soon, and with no concern for the collateral damage. The government liked to speak of an “abundance of caution,” but no such caution was exercised to prevent catastrophic societal harm. There was no attempt to undertake even a basic assessment of proportionality or foreseeable impact.

Even those who approached the Inquiry with modest expectations have been startled by how far it fell below them. As former Leader of the UK House of Commons, Jacob Rees-Mogg recently observed, “I never had very high hopes for the Covid Inquiry…but I didn’t think it would be this bad.” Nearly £192 million has already been spent, largely enriching lawyers and consultants, to produce 17 recommendations that amount, in his words, to “statements of the obvious or utter banality.”

Two of those recommendations relate to Northern Ireland: one proposing the appointment of a Chief Medical Officer, the other an amendment to the ministerial code to “ensure confidentiality.” Neither insight required hundreds of witnesses or years of hearings. Another recommendation, that devolved administrations should have a seat at COBRA, reveals, he argues, “a naiveté of the judiciary that doesn’t understand how this country is governed.”

Rees-Mogg’s wider criticism goes to the heart of the Inquiry’s failures, as it confuses activity with accountability. Its hundreds of pages record bureaucratic process while ignoring substance. The same modeling errors that drove early panic are recycled without reflection; the Swedish experience is dismissed, and the Great Barrington Declaration receives a single passing mention, as if it were an eccentric sideshow. The report’s underlying message never wavers: lockdowns were right, dissent was wrong, and next time the government should act faster and with fewer restraints.

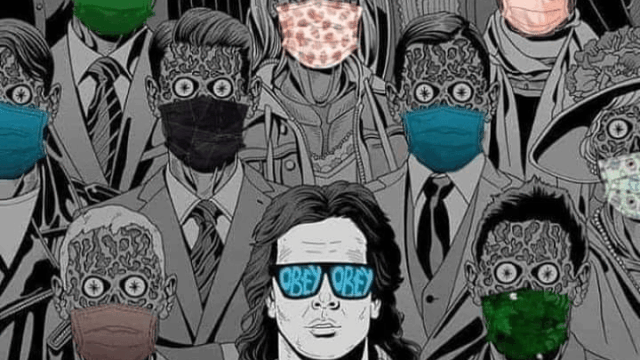

He also highlights its constitutional incoherence. It laments the lack of “democratic oversight,” yet condemns political hesitation as weakness. It complains that ministers acted too slowly, while elsewhere chastising them for bowing to public pressure. The result, he says, is “schizophrenic in its approach to accountability.” Behind the legal polish lies an authoritarian instinct, the belief that bureaucrats and scientists know best, and that ordinary citizens cannot be trusted with their own judgment.

The conclusions could have been drafted before the first witness entered the room:

- Lockdowns were necessary.

- Modelling was solid.

- Critics misunderstood.

- The establishment acted wisely.

It is the kind of verdict that only the British establishment could deliver about the British establishment.

The Inquiry treats the question of whether lockdowns worked as if the very question were indecent. It leans heavily on modeling to claim that thousands of deaths could have been avoided with earlier restrictions, modeling that is now widely recognised as inflated, brittle, and detached from real-world outcomes. It repeats that easing restrictions happened “despite high risk,” yet fails to note that infection curves were already bending before the first lockdown began.

Here Baroness Hallett makes her headline claim that “23,000 lives could have been saved” if lockdowns had been imposed earlier. That number does not come from a broad evidence base, but from a single modelling paper written by the same scientist who, days later, broke lockdown to visit his mistress because he did not believe his own advice or modeling figures. Treating Neil Ferguson’s paper as gospel truth is not fact-finding. It is narrative protection.

Even Dominic Cummings, Boris Johnson’s most influential adviser in early 2020, has accused the Inquiry of constructing what he calls a “fake history.” In a detailed post on X, he claimed it suppressed key evidence, ignored junior staff who were present at pivotal meetings, and omitted internal discussions about a proposed “chickenpox-party” infection strategy. He argued that the Inquiry avoided witnesses whose evidence would contradict its preferred story, and he dismissed the “23,000 lives” figure as politically spun rather than empirically credible. Whatever one thinks of Cummings, these are serious allegations from the heart of government, and the Inquiry shows little interest in addressing them.

It quietly concedes that surveillance was limited, urgency lacking, and spread poorly understood. These admissions undermine the very certainty with which it endorses lockdowns. Yet instead of re-examining its assumptions, the Inquiry sidesteps them. To avoid reconsidering lockdowns is to avoid the very heart of the matter, and that is exactly what it does.

During 2020 and 2021, fear was deployed and amplified to secure compliance. Masks were maintained “as a reminder.” Official documents advised that face coverings could serve not only as source control but as a “visible signal” and “reminder of COVID-19 risks,” a behavioural cue of constant danger.

The harms of lockdown are too numerous for a single list, but they include:

- an explosion in mental health and anxiety disorders, especially in children and young adults

- a surge in cancers, heart disease, and deaths of despair

- developmental regressions in children

- the collapse of small businesses and family livelihoods

- profound social atomisation and damage to relationships

- the erosion of trust in public institutions

The Inquiry brushes over these truths. Its recommendations focus on “impact assessments for vulnerable groups” and “clearer communication of rules,” bureaucratic language utterly inadequate to address the scale of the damage.

It also avoids the economic reckoning. Pandemic policy added 20 percent of GDP to the national debt in just two years, a cost already passed to children not yet old enough to read. That debt will impoverish their lives and shorten life expectancy, since wealth and longevity are closely linked.

Whenever Sweden is mentioned, a predictable chorus appears to explain away its success: better healthcare, smaller households, lower population density. Yet it is also true that Sweden resisted panic, trusted its citizens, kept schools open, and achieved outcomes better than or comparable to ours. The Inquiry refers vaguely to “international differences” but avoids the one comparison that most threatens its narrative. If Sweden shows that a lighter-touch approach could work, the entire moral architecture of Britain’s pandemic response collapses, and that is a question the Inquiry dares not ask.

The establishment will never conclude that the establishment failed, so the Inquiry performs a delicate dance:

- Coordination was poor, but no one is responsible.

- Communications were confusing, but the policies were sound.

- Governance was weak, but the decisions were right.

- Inequalities worsened, but that tells us nothing about strategy.

It acknowledges everything except the possibility that the strategy itself was wrong. Its logic is circular: lockdowns worked because the Inquiry says they worked; modeling was reliable because those who relied on it insist it was; fear was justified because it was used; Sweden must be dismissed because it challenges the story.

At times, reading the report feels like wandering into the Humpty Dumpty chapter of Through the Looking-Glass, where words mean whatever authority decides they mean. Evidence becomes “established” because the establishment declares it so.

A serious, intellectually honest Inquiry would have asked:

- Did lockdowns save more lives than they harmed?

- Why was worst-case modeling treated as fact?

- Why were dissenting voices sidelined?

- How did fear become a tool of governance?

- Why did children bear so much of the cost?

- Why was Sweden’s success dismissed?

- How will future generations bear the debt?

- How can trust in institutions be rebuilt?

Instead, the Inquiry offers administrative tweaks, clearer rules, broader committees, and better coordination that studiously avoid the moral and scientific questions. An Inquiry that evades its central task is not an inquiry at all, but an act of institutional self-preservation.

Perhaps we should not be surprised. Institutions rarely indict themselves. But the cost of this evasion will be paid for decades, not by those who designed the strategy, but by those who must live with its consequences: higher debt, diminished trust, educational loss, social fracture, and a political culture that has learned all the wrong lessons.

The Covid Inquiry calls itself a search for truth, but the British establishment will never allow something as inconvenient as truth to interfere with its instinct for self-preservation.

https://brownstone.org/articles/how-the-covid-inquiry-protected-the-establishment