AIPAC Isn’t Alone

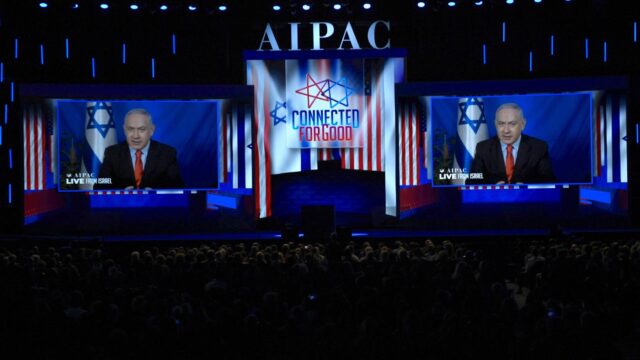

Many on the American right have begun voicing growing discomfort with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, not because its methods are mysterious or concealed, but because the organization operates with an efficiency and confidence that reveal how easily the American political machine can be steered by outsiders who understand its mechanics. AIPAC has long supported politicians in both parties, invested heavily in cultivating professional lobbyists, and maintained a sophisticated internal apparatus dedicated to securing legislation favorable to Israel.

Observers in Washington often remark that the committee is particularly adept at circulating detailed talking points to members of Congress, offering them ready-made arguments for defending Israel during moments of geopolitical tension. This pattern became especially visible during the long-running debates about Iran’s nuclear ambitions, when Israel carried out strikes on Iranian targets and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee responded by urging Congress to adopt a more confrontational posture and reiterate Israel’s strategic concerns. These episodes illustrate how closely the committee monitors international events and how quickly it moves to shape the American response.

If the American public wishes to grapple seriously with the issue of foreign influence in their politics, the first step is to recognize that AIPAC is not a unique anomaly but one manifestation of a broader phenomenon in which foreign governments, wealthy diasporas, and international institutions learn to operate within the American political system with remarkable fluency. In fact, the entire landscape of American governance has become a field in which external actors, recognizing the opportunities available to them, pursue their interests with a level of organization that American citizens themselves rarely appreciate.

Qatar provides one of the most striking illustrations of how this process works. Over the past two decades, the Qatari state and its affiliated foundations have invested billions of dollars into American universities, securing influence not through noisy political campaigns but through the quiet, steady accumulation of goodwill in elite academic spaces. Georgetown University and Northwestern University have been among the most prominent beneficiaries of Qatari funding, and in the case of Northwestern, the university even signed an agreement with the Qatar Foundation that prohibits it from criticizing the Qatari regime. This arrangement reveals much about the nature of modern influence building, for it shows how foreign governments can embed themselves in the intellectual infrastructure of the United States, shaping perceptions and priorities from within institutions that are traditionally viewed as independent arbiters of knowledge.

South Korea has pursued a path that differs in surface appearance yet mirrors the same underlying logic. Between 2016 and 2024, South Korea became the fifth largest foreign spender on lobbying related to American foreign policy. Rather than relying primarily on blunt political advocacy, South Korean interests have built a network of think tanks and cultural institutes devoted to studying the relationship between the United States and South Korea. These institutions present themselves as neutral research organizations, yet they play a crucial role in setting the terms of policy debate, providing expert commentary that guides Congressional hearings, shaping media narratives about the Korean Peninsula, and circulating conceptual frameworks that subtly align American thinking with South Korea’s strategic priorities. Their influence is woven into the intellectual fabric of policymaking rather than proclaimed through overt political slogans, which makes it both more palatable and more effective.

The Indian diaspora offers a further example of how diasporic groups can shape American policy with surprising sophistication. For many years, Indian-American activism was overshadowed by immigration debates and technical disputes surrounding H-1B visa allocations. However, as the diaspora gained economic power and cultural confidence, it increasingly embraced its role as an agent of Indian influence abroad. Today, Indian-American networks participate in an intricate blend of formal lobbying, informal advocacy, and social capital exchanges that advance India’s interests within the United States. Their efforts reflect an enduring truth about diaspora communities: they instinctively practice tribal politics because tribal politics works. A diaspora, by its very nature, extends the influence of its homeland by leveraging the opportunities available in its host society, and the Indian community has mastered this with the same strategic intelligence seen in the actions of Qatari institutions and South Korean policy networks.

From the standpoint of these groups, such behavior is not only rational but laudable. They protect their homelands, strengthen their networks, and use the considerable openness of American institutions to project influence across the world. Tribal politics, in this sense, is a sign of strategic maturity, for it recognizes that identity, loyalty, and shared interests can be powerful tools in shaping international affairs. Yet the success of these efforts also indicates something important about the American situation. The influence these groups exert is not aimed at advancing American interests. It is aimed at advancing the interests of their own nations, which is precisely what diasporas have always done. The problem arises only because Americans seldom pay attention to these dynamics, and therefore fail to appreciate how deeply foreign influence has permeated their political and intellectual structures.

What stands out most of all is the unevenness of American scrutiny. Much of the public debate focuses intensely on the lobbying activities associated with the Jewish diaspora, which consumes a disproportionate share of political commentary, while the influence-building of Qatar, South Korea, India, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates continues almost unnoticed. Even when attention does shift, it is usually triggered by partisan controversy rather than a sustained examination of how foreign policy lobbying actually functions. The current fixation on Qatar, for example, has less to do with a broad inquiry into Qatari influence and more to do with the perception that certain right-wing commentators may have connections to Qatari financial networks. This selective outrage obscures the larger truth that the United States has become a stage on which numerous foreign actors compete to shape policy outcomes, each pursuing its own interests with remarkable determination.

If Americans wish to reclaim a clearer understanding of their political landscape, they would benefit from studying foreign policy lobbying with far greater seriousness. Diasporas will continue to project influence abroad because doing so is in their nature and in their interest. Foreign governments will continue to invest in American institutions because such investments yield extraordinary strategic returns. The question facing the United States is whether its citizens possess the awareness and the will to understand how these forces operate and to consider how the American political system should respond. Only by confronting these realities with curiosity and clarity can Americans begin to understand the full scope of external pressures that shape the policies made in their name.