How Big Pharma Mixed Addiction With So-Called ‘Social Justice’

Opioid marketing teams planned to “educate women in their natural settings” — including “Tupperware parties” — that female “empowerment” meant demanding more pain pills.

One of America’s most infamous corporate characters just made its final curtain call. The $7 billion bankruptcy deal approved over the holidays for Purdue Pharma and its billionaire owners, the Sackler family, includes compensation for individuals harmed by OxyContin® or other prescribed opioids: from $3,500 to $16,000 (before legal fees), available to anyone who filled out the right paperwork a long time ago and who promises not to sue. The payments might begin as soon as this March.

Purdue, with a new name (Knoa Pharma) and under new management, gets to re-dedicate itself now to treating opioid addiction. As an ER doctor also board-certified in addiction medicine, I’ve spent years reviving (or failing to revive) people who’ve overdosed on fentanyl or heroin or oxycodone, and who more often then not, first got hooked on opioids via a prescription from a doctor.

I’ve also spent years commiserating with other doctors about how, back in the day, we were set up to fail our patients, thanks to a confused mishmash of nonsense about how no one gets addicted to modern opioid therapy anymore. Yet even today — after all of the multi-billion-dollar settlements and lawsuits, after hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths, after hearings and speeches in Congress — few people seem to really understand how coldly and methodically Purdue (and other opioid manufacturers, but especially at Sackler-led Purdue) worked at getting people addicted. They focused in marketing and sales trainings on the need not just to convince doctors to start patients on opioids, but to keep them on opioids, and at the highest achievable doses.

As laid out in particularly withering detail in the Massachusetts and New York state lawsuits, Purdue had an opioid sales strategy for every American identity group with good insurance. They targeted the elderly, using “profiles of fake elderly patients, complete with staged photographs” to convince doctors to prescribe opioids. They targeted veterans, who in my state of Massachusetts are are three times more likely to die of a drug overdose than non-veterans — but they do have great insurance!

Purdue, both directly and through front organizations like the American Pain Foundation, even came up with the idea that getting addicted to OxyContin could be a form of feminist self-actualization. Under the heading “Empowerment — women,” notes from a marketing strategy session elaborate approvingly that the “empowerment angle can be used with any program.” And that wasn’t all:

First, a note about the bankruptcy deal, which may surpass even Lehman Brothers as perhaps America’s all-time example of “fraudulent conveyance,” the practice of moving money out of the reach of creditors. At least in terms of shamelessness, the company has no peer.

In the years before the 2007 watershed plea deal, the Sacklers as owners of Purdue had been taking out a tidy 15% of annual revenues for themselves. But after 2007 — even as they massively escalated their deceptive sales and marketing, and even as opioid-associated lawsuits against the company started piling up — the Sacklers read the writing on the wall. They started taking home 70 percent (!) of revenues.

“[T]he Sacklers initiated a ‘milking program,’ withdrawing from Purdue approximately $11 billion — roughly 75% of the firm’s total assets — over the next decade,” was how the clearly disgusted judges of the U.S. Supreme Court described the technique. The U.S. Justice Department referred to these withdrawals as “fraudulent transfers.”

The current Supreme Court is a generally pro-business, corporate-friendly collection of men and women in matching silly robes, but even they have standards. When the Sacklers offered to return $4.3 billion to Purdue’s bankruptcy estate (in occasional installments, over many years), in exchange for a judicial order that they could never be sued for any past or future opioid-related claim by anyone — that was too much even for this Supreme Court, which said “no,” returning the case to bankruptcy court.

The just completed revised deal stipulates that the Sacklers — who’ve had medical schools and a wing at The Met named in their honor — can no longer request naming rights in return for charitable donations. That’s a relief, as I fervently hope to die without ever seeing the solemn announcement of someone at Knoa Pharma proudly accepting the First Annual Richard Sackler Award for Public Service, or some other such atrocity.

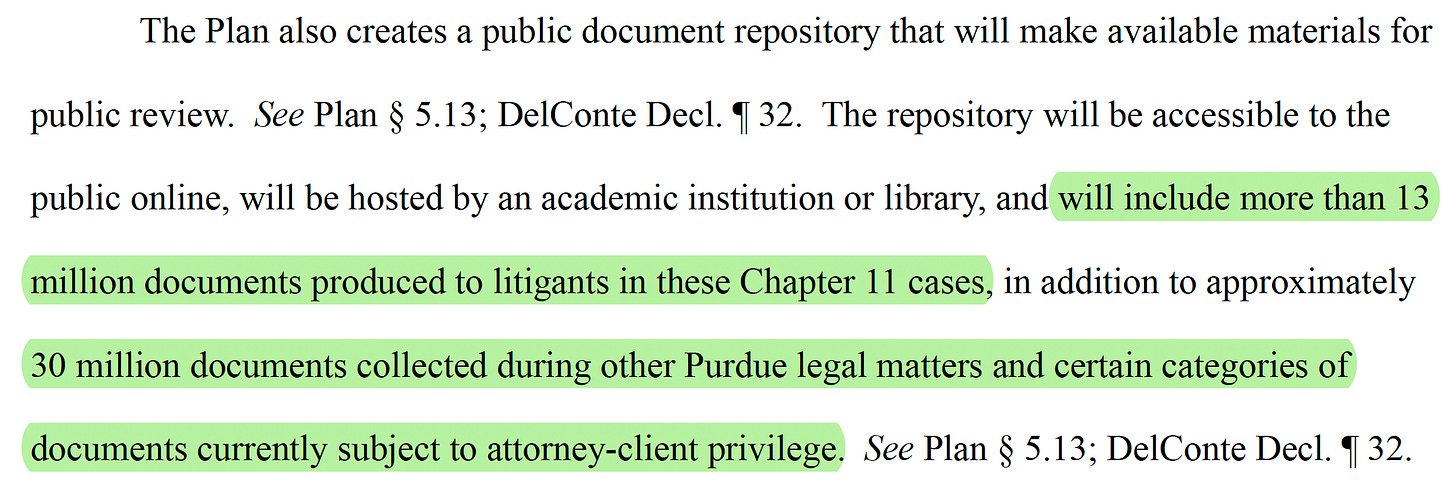

No, I’ve suffered enough mental trauma just browsing for countless days through the indispensable digital archive of more than 6 million opioid industry-related documents maintained by University of California, San Francisco. As an aside, the bankruptcy deal — which calls itself “The Plan” — promises to deliver up 43 million more documents to the public soon:

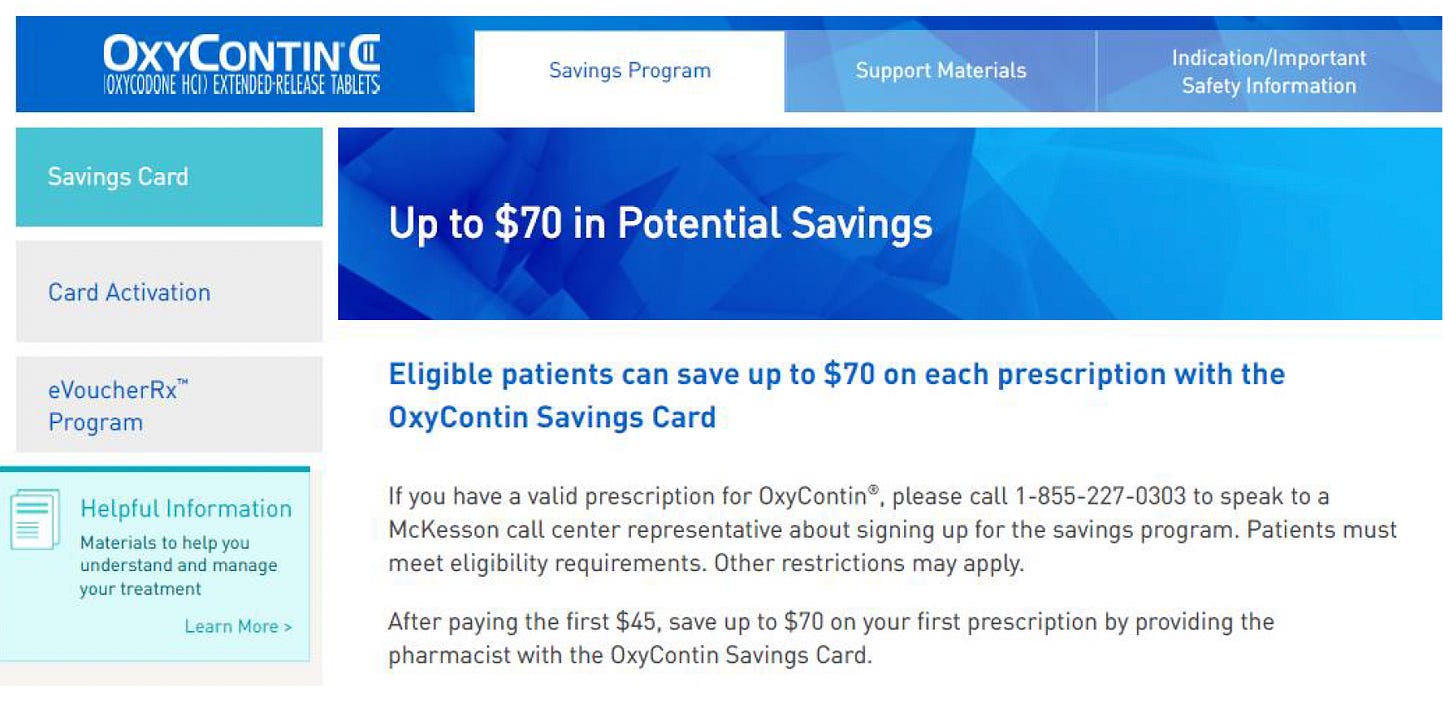

Even the documents we have now amply document the banality of this evil. One of Purdue’s best investments was the introductory savings card for OxyContin®, a discount coupon that sales staff hand-delivered to doctors’ offices or mass e-mailed.

Purdue’s internal analysis showed these had a phenomenal return on investment: Every $1 million spent on OxyContin® savings cards translated into $4.28 million in revenue. The savings cards “helped” patients afford to try opioid therapy — with the result that many would end up trapped on opioids long term.

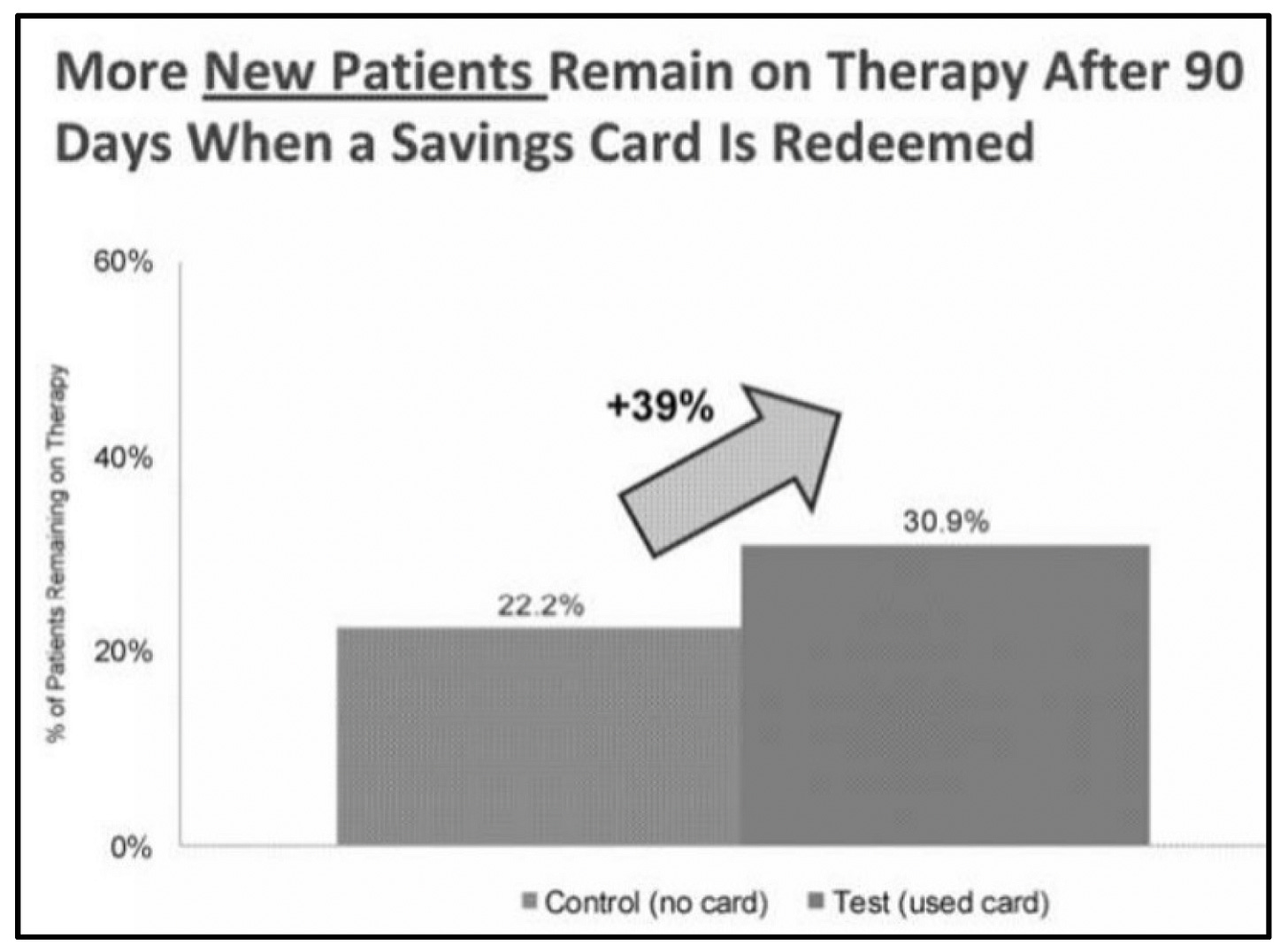

Consider some PowerPoint slides:

That slide celebrated how a savings card up-front made it far more likely the patient would be stuck on OxyContin® three months later. That may be bad for the patient, but it’s good for Purdue. Never mind that the Massachusetts Department of Public Health found that patients still on prescription opioids after 90 days were four times more likely to die of an opioid overdose in the next year, and 30 times more likely to die of an overdose in the next five years. From Purdue’s point of view, if the patient’s on OxyContin® after 90 days, that’s some fine work.

And it’s even better work if the doses have been rising steadily.

OxyContin® tablets, usually taken twice daily, start at 10 mg and rise up to 80 mg. (There was even briefly a 160 mg tablet, for about nine months, back in 2000-2001. Purdue “voluntarily” stopped marketing it. It’s incredible to think of such dosing — the equivalent of taking an entire bottle of 64 standard Percocet® pills every day.)

Purdue would charge more for higher doses. (Like every good drug dealer, it sold product by weight.) The Massachusetts Attorney General’s office, looking at 2015 price lists, calculated that a patient on low-dose OxyContin® for one week would earn Purdue $38. That same patient on the high-end dose brought in $210, or more than five times as much.

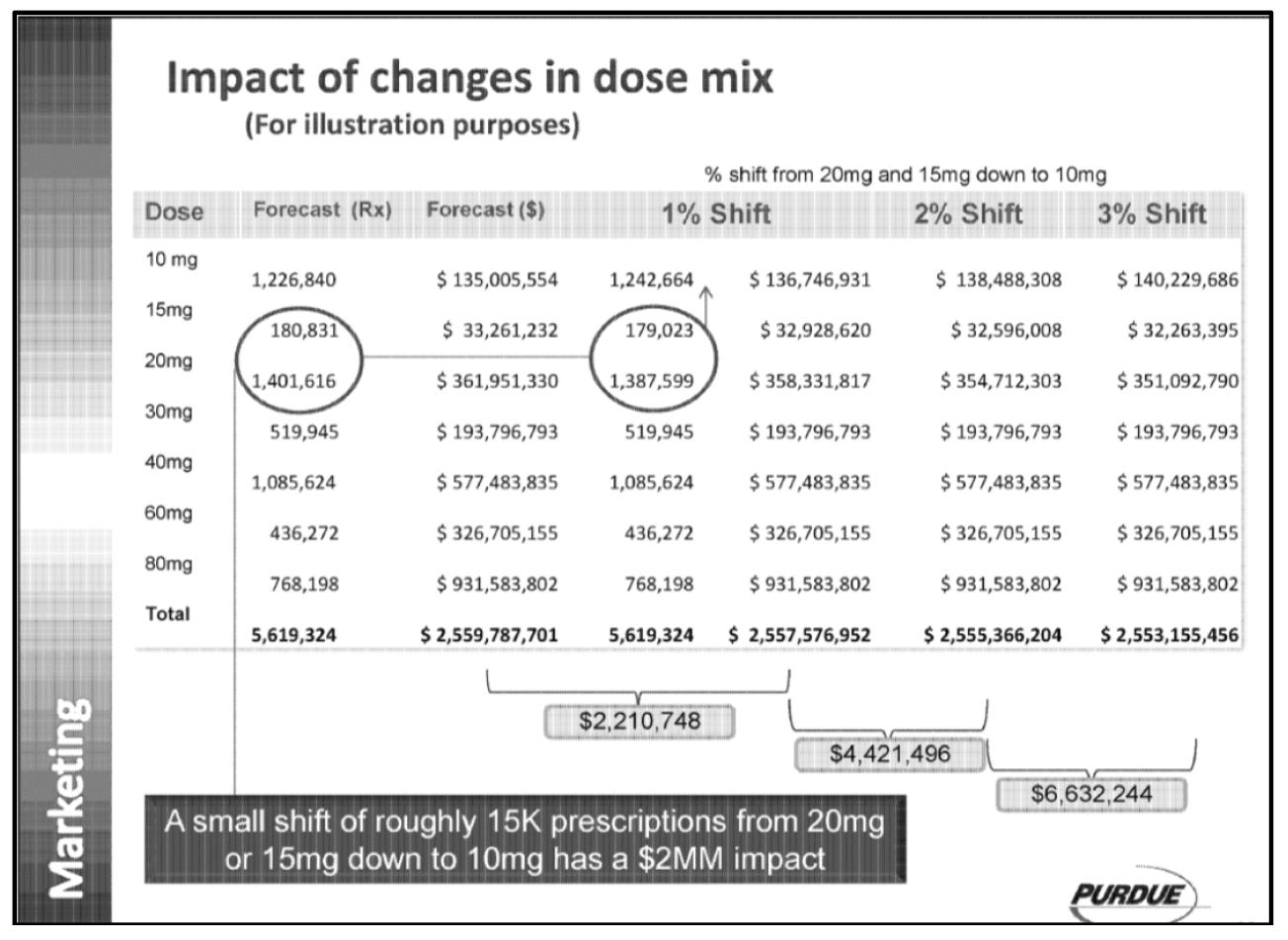

Purdue was frank about the implications of such math, and in presentations showed staff how even small fluctuations in the milligrams prescribed could sway millions of dollars. In the slide below, the marketing department considers what happens if patients taking 15 mg or 20 mg doses get scaled back — by some unexpected outbreak of common sense or mass do-gooderism — to 10 mg doses.

If that modest correction happens with just 1% of patients, Purdue ends up losing $2.2 million.

If in 2% of cases, $4.4 million.

If, God forbid, 3% of patients reduce by a few milligrams their opioid intake, $6.6 million could be lost.

We don’t have all of the details of this presentation, so it’s unclear what time frame or geographic area is being considered. The point is: Purdue told its marketing staff that millions of dollars will move up or down as medication dosing is titrated up or down. Among other things, this affected the sales staff’s commissions.

“Titration” — the medical term for adjusting a dose until a desired effect is achieved — therfore became a sales obsession. Sales staff had to “practice verbalizing the titration message” at workshops, where they’d be told not just the stats on how many new prescriptions the sales force had brought in — but specifically how many high-dose up-titrations. (For completeness, the trainings also talked about titrating back down in a stepwise fashion, to prevent opioid withdrawal symptoms — but these were sales team trainings, not medical trainings, and titrating sales down was never the emphasis.) Meanwhile, ads in journals would help doctors see how to climb the titration ladder:

What’s more, Purdue’s business teams crunched the numbers and found that higher doses encouraged longer treatment courses — so if you can get the patient titrated up to 60 mg or 80 mg, chances are you’d see not just one week’s worth of profits, but profits for months or years.

A patient kept on the highest dose of OxyContin® for a year, per the Massachusetts attorney general, brought in $10,959.25.

Which sounds like better business: earning a one-time $38 from a patient with back pain, or $10,959 every year from that same patient’s back pain?

The choice isn’t hard. So, the business goal was clear: Push doctors (and other prescribers) to titrate toward higher OxyContin® doses, supposedly in a search of that sweet spot for symptom control, but actually because daily, high-dose opioid exposure turns people into opioid addicts loyal customers.

“There is a direct relationship between OxyContin LoT [Length of Treatment] and dose,” observed a Purdue internal marketing presentation in 2012.

Eventually, Purdue launched an OxyContin® campaign around the slogan “Individualize the Dose.” But this had little to do with finding the appropriate medical treatment for a given individual. Why, if that had been the idea, many would probably still be taking Tylenol® or ibuprofen. No, this was discussed in Purdue documents, and presented at board meetings, as a marketing initiative. It was about moving product. “Individualize the Dose” came up in the same context as celebrations when high-dose OxyContin® was on the rise, and handwringing when prescribers started getting shy.

‘Let women addict educate women in their natural settings’

It’s worth remembering that none of this was happening in a vacuum. Makers of opioids everywhere, undaunted by Purdue’s 2007 guilty plea and fine, were not just telling doctors that “modern opioids were safe”; they were also telling patients that they had a God-given right to be pain-free, and to demand that their doctors see them, hear them and treat them. Everyone from the Joint Commission to the American Medical Association to the American Pain Foundation was singing some variation of that song.

In that regard, a “brainstorming session” in 2007 at the American Pain Foundation — a front organization funded by Purdue and other opioid manufacturers — continued a long-running riff on how the pain of women was not taken seriously by doctors. It was time, according to the notes of the session, to reframe opioid prescription as a discrimination issue. Access to pain meds, as they put it, meant “empowerment”:

Empowerment – Women:

“Empowerment angle can be used with any program,” the pain foundation team noted approvingly. It added, “encourage patients to advocate for their rights … Consider viral tactics/word of mouth education – let women educate women in their natural settings (e.g., Tupperware parties, garden groups, e-cards).”

Jane Brody, the New York Times health reporter, showed up to the metaphorical Tupperware party around then, with an account of weeks of severe pains after she took the unusual step of having both knees replaced at once.

“Most doctors are clueless or unnecessarily cautious about treating pain,” she wrote in her widely-read health column in 2005. “They are especially ill-informed about opioids.”

I wouldn’t mind seeing an indignant New York Times berate me and my fellow doctors by asking how we’d ever allowed this opioid crisis catastrophe. But no. Brody was complaining that we hadn’t been slinging enough dope! We needed to hand it out even more liberally! It reminds me of the famous Christopher Hitchens statement, “I became a journalist because I did not want to rely on newspapers for information.”

Over at Purdue, Brody’s complaints — her loud advocacy for everyone’s right to be pain-free after surgery — must have been a marketing Godsend:

“I did not know that the dose of the sustained-release opioid OxyContin (oxycodone) that I was taking — 20 milligrams twice a day — was a ‘low’ dose until seven weeks after surgery. [Note: 40 mg a day is not “a low dose”. It’s equal to taking eight oxycodone / Percocet® tablets a day!]

“I also did not know that the other pain drug I was prescribed for breakthrough pain, Percocet, was really short-acting oxycodone plus acetaminophen. Because my pain was frequently intolerable despite the two doses of OxyContin, I was taking as many as 10 Percocets a day. [Note: So, she was taking the equivalent of 18 Percocet a day?] … Yet, when I complained about the severity of my pain, which had me crying for several hours a day, the surgeon added an anti-inflammatory drug and told me to take half the OxyContin and Percocet.

In other words, the surgeon dealing with this querulous and powerful woman took on a thankless task, and got himself savaged in the pages of The New York Times, because he advocated for her long-term health over short-term comfort. He told her for her own good to toughen up, scale back on the massive opioid doses, and maybe be more philosophical about the pain inherent in opting for simultaneous knee replacements. Any physician can tell you: It’d have been much quicker and easier to titrate up her OxyContin® dose.

Brody has written followup columns in years since about the joys of bilateral knee replacements. She’s described dancing, and touring Vietnam by bicycle. She retired in 2022 but is still going strong at 84, doing podcasts and judging contests. She did not respond to a Racket query.

One wonders what would have happened to her if her surgeons, instead of trying to wean her off of opioids in those few crucial weeks, had bowed to “Empowerment — Women,” and set out to “Individualize Jane Brody’s Dose”. If she’d been rapidly titrated up to OxyContin® 80 mg twice daily — the equivalent of 32 Percocet® pills every day — would she have continued to be a functioning New York Times reporter? Would she even be alive today?

https://www.racket.news/p/how-big-pharma-mixed-addiction-with