Venezuela — Power Without Justice

The American Government and the Corruption of Moral Reason.

This article is not primarily about Venezuela. It is about the United States Government, and about what prolonged power does to a ruling class that has ceased to believe it is morally accountable. The American attack on Venezuela is important not because it is unique, but because it is revealing. It exposes the internal moral condition of the American state more clearly than a hundred plainly hypocritical speeches about democracy or freedom ever could.

The operation was not the result of panic or confusion, let alone sudden necessity. It was planned, justified, narrated, and celebrated. It therefore cannot be excused as error. It must be judged as character. What we are examining here is not a policy failure but a moral failure, rooted in habits of domination that have hardened into instinct. Just War theory is not being applied as an abstract theological exercise. It is being used as a diagnostic instrument, to show that the American Government no longer recognises moral limits on its own power.

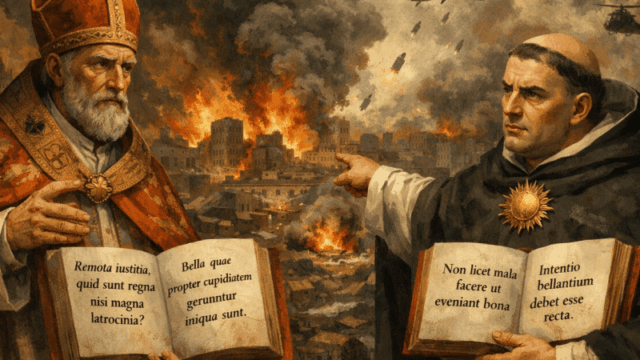

The Just War tradition exists precisely for such moments. It was not designed for saints governing small communities, but for empires tempted to identify their own interests with the good of the world. It begins from the assumption that power lies to itself, and that the greater the power, the more persuasive the lie becomes. Augustine and Aquinas are therefore not decorative authorities. They are hostile witnesses.

Augustine of Hippo wrote as a man who had watched an empire justify everything and restrain nothing. Rome was rich in legal forms and poor in justice. It spoke endlessly of order while practising plunder. Augustine’s political theology is shaped by disgust at this hypocrisy.

His most famous indictment appears in De Civitate Dei IV.4:

“Remota iustitia, quid sunt regna nisi magna latrocinia?”

With justice removed, what are kingdoms but great bands of robbers?

This is not rhetoric. It is definition. Augustine is saying that power without justice does not merely resemble criminality. It is criminality, differing only in scale and organisation. The American operation against Venezuela fits this definition with chilling precision. It involved the violent seizure of a foreign leader under the pretence of law, justified by unilateral accusations, executed with military force, and followed by legal theatre. That is not law. It is robbery with paperwork.

Augustine is equally clear about motive. In Contra Faustum XXII.74, he strips away the moral camouflage of war:

“Libido dominandi, crudelitas ulciscendi, feritas implacabilis animi, fervor rebellionis, libido nocendi—haec sunt quae in bellis iure culpantur.”

The lust for domination, the cruelty of revenge, the savagery of an implacable spirit, the fever of rebellion, the desire to do harm—these are the things which are rightly condemned in wars.

The American Government’s behaviour displays libido dominandi in its purest modern form: the assumption that no one has standing to resist American will, and that resistance itself is proof of guilt. Venezuela’s crime was not merely corruption or repression. It was defiance. It sold oil outside the preferred monetary system. It refused to behave as a subordinate client. It asserted a degree of independence incompatible with American managerial empire. That, far more than drugs or human rights, explains the intensity of the response.

Augustine also insists that war may be tolerated only when ordered to peace. In Epistula 189, he writes:

“Non pax quaeritur ut bellum excitetur, sed bellum geritur ut pax acquiratur.”

Peace is not sought in order to provoke war, but war is waged in order that peace may be obtained.

This sentence alone condemns the American action. The operation was not aimed at peace. It was aimed at control, deterrence, and example. It was a message to other states contemplating disobedience. Such signalling wars are explicitly excluded by Augustinian morality. War ordered toward intimidation is not war ordered toward peace. It is terror.

If Augustine exposes the moral psychology of unjust power, Thomas Aquinas provides the juridical framework America has deliberately dismantled. Aquinas’s account of war in Summa Theologiae II–II, q.40 is brief because it is meant to be restrictive. War is not a normal instrument of policy. It is an emergency measure permitted only under strict conditions.

Aquinas begins with authority:

“Ad bellum iustum requiritur auctoritas principis, ad quem pertinet respublica.”

For a just war there is required the authority of the sovereign, to whom the care of the commonwealth belongs.

This authority is not global. It is bounded by responsibility for a particular political community. American domestic courts do not possess moral authority over Venezuela. To claim otherwise is to assert imperial jurisdiction, which Aquinas does not recognise. Authority detached from responsibility becomes domination.

Aquinas then defines just cause:

“Causa iusta requiritur, ut scilicet illi qui impugnantur, propter aliquam culpam impugnationem mereantur.”

A just cause is required, namely that those who are attacked should deserve it on account of some fault.

This clause is routinely abused. Aquinas does not mean moral wickedness in general. He means unjust aggression or refusal of restitution. Criminal accusations, corruption, or tyranny within a state do not license foreign invasion. Aquinas is explicit elsewhere that punishment belongs to legitimate authority within a community. External force is justified only to repel force.

The American Government collapsed this distinction deliberately. It treated indictment as aggression and prosecution as defence. This is not a misunderstanding of Aquinas. It is a rejection of him.

Most damning of all is intention. Aquinas writes:

“Intentio bellantium debet esse recta.”

The intention of those waging war must be upright.

He then adds the decisive qualification:

“Bellum autem fit iniustum propter intentionem pravam, puta cum aliquis intendit nocere vel dominari.”

War becomes unjust because of a wicked intention, for example when someone intends to cause harm or to dominate.

Domination is named explicitly. When American officials speak openly of managing Venezuela’s transition, reopening its oil sector, reintegrating it into preferred markets, and disciplining others by example, intention is no longer concealed. The war was not about restoring peace. It was about asserting hierarchy.

Even if cause and authority had been present—which they were not—the American operation fails on proportionality. Over 150 aircraft were deployed. Bombing was used as distraction. Venezuelan personnel were killed. Civilian risk was knowingly accepted. Aquinas rejects consequentialist reasoning without ambiguity:

“Non licet mala facere ut eveniant bona.” (ST I–II, q.18, a.4)

It is not lawful to do evil that good may result.

The seizure of one man does not justify exposing a population to death. Precision does not redeem injustice. Nor does technological superiority excuse contempt. What we see instead is something worse: moral indifference to foreign life. This is the surest sign of corruption. When a state no longer even bothers to pretend that foreign lives matter equally, it has crossed from arrogance into evil.

The simplest test remains reciprocity. If Russia, China, or Iran seized an American leader under domestic criminal charges, Americans would call it an act of war. They would be correct. The satirical address by Mr Putin that the Libertarian Alliance published yesterday rests on entirely serious assumptions about the moral law: What is good for one must be good for others. Aquinas’s framework exists to enforce this symmetry. A moral rule that applies only when convenient is not a moral rule at all.

The American Government knows this. Its leaders are not confused. They are cynical. That is what makes the action so grave. It is not ignorance of Just War theory that condemns them. It is contempt for it.

Donald Trump’s role in this corruption is decisive. Under his leadership, what had once been reckless stupidity has hardened into settled vice. He does not merely continue imperial habits. He has stripped them of shame. He has mocked restraint, celebrated domination, and treated foreign policy as spectacle. In doing so, he taught his followers that power needs no moral justification beyond success.

Augustine warned that success is morally meaningless. In Quaestiones in Heptateuchum VI.10, he writes:

“Bella quae propter cupiditatem geruntur, etiam si felicia sint, iniqua sunt.”

Wars which are waged out of greed are unjust, even if they are successful.

This judgement applies directly. The American operation may succeed tactically. It may deter others. It may secure resources or monetary compliance. None of this redeems it. Success merely confirms capability, not justice.

By Augustinian and Thomistic standards alike, the American attack on Venezuela is not a borderline case. It is a clear instance of unjust war. There was no just cause, no legitimate authority, no right intention, no exhaustion of peaceful alternatives, no proportionality, and no adequate discrimination between combatants and innocents.

More than this, it reveals a government that no longer believes itself morally bound. That is the true danger. When the most powerful state on earth discards restraint, it does not merely commit injustice. It teaches the world that injustice is the rule.

If Just War theory means anything at all, then the American Government stands condemned—not for error, but for corruption.

https://nickgriffin544956.substack.com/p/venezuela-power-without-justice