The Death of Noblesse Oblige, the Age of Revolution, and Us

The public school account of the French Revolution usually says it was a justified uprising of “the people” against a hopelessly awful ruling class, so-called nobles, royals, and priests who were really mean to the commoners and who got their proper comeuppance. Even if the revolutionaries chopped off a few too many heads in the rush of the moment, their excesses are mostly forgivable because they meant well and wanted equality—which in the end is all that matters. That was the point of the Revolution.

Such a facile story ought to be laughed at by anyone halfway interested in actual history, but there’s a reason why it became the go-to narrative and why it can’t be dismissed too quickly. It lands close enough to be mistaken for the truth by those who demand soundbite knowledge.

This matters because the French Revolution was a no-turning-back moment for Western Civilization. Charles Emile Freppel called it “one of the most fateful events in human history.” To Kendall W Brown the Revolution was “a gate through which the western world passed into modernity.” Simon Schama similarly refers to an axiomatic consensus that it was “the crucible of modernity: the vessel in which all the characteristics of the modern social world, for good or ill, had been distilled.”

So if the French Revolution helped make the world we live in today, we ought to understand what made the Revolution—especially because the deeper problems which gave birth to it are still with us today. The driver of these troubles is the death of noblesse oblige: French for “nobility obligates,” the old idea that those with power, wealth, and privilege ought to be generous toward those with less. When noblesse oblige goes, trouble comes.

Revolution

In The Old Regime and the French Revolution, Alexis de Tocqueville argues that the nobles of 18th century France truly had become unimpressive, but not for the reasons we’ve been led to believe by democracy-enthusiasts, not because the privileged classes are always and everywhere awful. The tragedy of modern French history, Tocqueville argues, is that the nobility was strategically detached from the commoners by ambitious kings, with a bargain that allow the nobility to keep its privileges while being relieved of its duties. These duties would now be done by meddling bureaucrats who worked for the crown and always helped centralize its power.

In all times and places, royals and nobles are going to be in some tension. Nobles are checks on the king’s power and threats to him. So Louis XIV (reigning from 1643 to 1715) essentially offered them an arrangement they couldn’t refuse. For the aristocrats involved, this must have seemed like a sweet deal: all the reward, none of the obligation, noblesse without the oblige. Whereas the nobles of old had seen themselves as protectors and counselors to their people, the current batch left the estates of their ancestors and went seeking the delights and variety of the big city, thus making themselves into little more than absentee landlords—and dooming their posterity.

The demise of noblesse oblige goes hand-in-hand with political centralization. Nobles were (and still are) the key to localism; without them, local initiative and enterprise declined and any business now required the oversight of the crown’s bureaucrats. This was the point. “Government took a hand in all local affairs,” Tocqueville writes, “even the most trivial. Nothing could be done without consulting the central authority, which had decided views on everything.” He adds that the central administration “resented the idea of private citizens’ having any say in the control of their own enterprises, and preferred sterility to competition.” (Which should sound familiar to everyone in our own bureaucratic century.) The freedom and self-government which had blossomed in the Middle Ages were snuffed with the rise of centralized power.

I’ve long wondered why the French—or anyone really—could get so fired up about equality, which always struck me as a not-particularly-invigorating ideal, especially for a people with a heroic history like the French. Tocqueville presents the rage for equality as the inevitable consequence of royal policy. Once upon a time in the Middle Ages, everyone understood that those privileges enjoyed by the warrior class were earned—because the nobles were actually noble and risked themselves. Now that was no longer the case, and the population was galled to suffer undeserved privileges enjoyed by undeserving people. Life in 18th century France violated a man’s sense of justice. So when the match of reform was struck, a bunch of dry kindling was ready to be ignited. “The more these functions passed out of the hands of the nobility,” Tocqueville writes, “the more uncalled-for did their privileges appear—until at last their mere existence seemed a meaningless anachronism.”

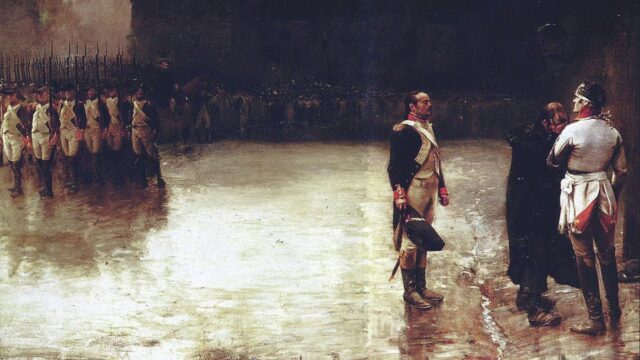

This is the backdrop of resentment and mismanagement against which the French Revolution played out. The death of noblesse oblige ushered in the Age of Upheaval, and everything time-honored and premodern was thrown out, and a lot of heads rolled, and a lot of wars were waged.

Us

We still live with this reality. After the grand experiment in egalitarianism failed to go as the reformers had planned, we still have all of the old problems in full. Instead of equality we have laundered oligarchy—the rule of billionaires, tycoons, experts, and managers who embody the exact opposite of noblesse oblige (and who actually aren’t impressive in any way except for their ability to game the system). These new oligarchs experience no such pressure to do right for those beneath them; instead they dedicate themselves to extracting from them.

Almost every aspect of modern American life is defined by the oligarchic mode of demeaning, demoralizing, and extracting from normal people—from the mass immigration which drives wages down and housing prices up, to the ugly architecture, sports-betting apps, weed dispensaries, homo entertainment, and more. Big Medicine now has little to do with promoting health and everything to do with managing and medicating sickness. Big Food, seemingly in cahoots with Big Medicine, has poisoned just about everything on the shelves of our grocery stores. Meanwhile fake experts make the matter still worse by confusing you with bad advice about what’s healthy and what’s good. “A patient cured is a customer lost,” they say—and this pattern applies almost uniformly across American life. The point is that our “elites” don’t give a damn about you and have turned our country into a “sheep-shearing operation,” as one poet put it.

This is one of the single worst fates that can befall a people. Any society, if it is to flourish, needs shepherds, guardians, counselors at the top. They set the tone. Instead we have predatory jackballs who have monetized your ruin.

We are all Frenchmen now, living through a series of revolutions, with more yet to come.

An Exception

Tocqueville adds that there was a major exception to the trend of ignoble nobles, one place in particular where they remained tied to the land and to their people. “This is particularly interesting,” he writes, “because the province in question is Anjou.”

Anjou was later named the Vendée.

And it was here that the nobles and the peasants joined in opposition to Parisian radicalism and actually took up arms against it in one of history’s greatest counter-revolutions. Farmers with scythes, led by actual nobles, won a series of stunning battles against the professional armies of the regime. Napoleon himself later said that the rebels could have marched on the capital city and overturned the entire Revolution, if only they hadn’t needed to return to their farms after every battle. Over time the machine redoubled its efforts and bested the Vendéans, and the region suffered catastrophic losses. But it will not do to say the Vendéans “lost” the war. Among other things, the rebels made the regime rethink the suppression of Catholicism within France, and a tremendous revival of the Faith followed in the wake of their glorious martyrdom. This is a fascinating episode of Western history, well-deserving of devoted study, but for the purposes of this essay remember this point: the uprising arose in a place where the nobles remained noble, and the cooperation of nobles and commoners opened up grand possibilities. “What made it feasible to put up this heroic resistance,” Tocqueville says, “ was the fact that [the nobles of Anjou] had always been on close and friendly terms with [their] peasants.”

There are no easy answers to our problems. But there will be opportunities, probably on a smaller scale, for leadership and goodness in the days ahead. It’s our job to be on the lookout and to make ourselves ready for the moment. People will be depending on us.

https://thechivalryguild.substack.com/p/the-death-of-noblesse-oblige-the