Britain’s Forgotten Race Riots of 1919

The trouble that has flared over immigration in the United Kingdom in the last two years is not without precedent. A previous burst of non-white immigration also led to serious violence as the indigenous took to the streets to protest against criminality, cheap labour and miscegenation

In Britain, just as in the USA, a central plank of pro-immigration propaganda is that “we have always been a nation of immigrants”. Why the fact that Britain was settled by different but closely related tribes of North West European – or that the modern USA was created by a mixture of Europeans – should be any reason to flood them with non-Europeans, from vastly different cultures, is never explained.

In a related propaganda deception, the proponents of mass immigration into the UK always seize upon the faintest evidence of a historical non-white presence in Britain as proof of a long history of multiculturalism. The establishment of small African enclaves in British port cities during World War One is a particular favourite in such circles.

Yet the actual history of that wave of settlement, the trouble it caused, and the way in which it came to a thoroughly messy end, is something which the liberals prefer to brush under the carpet. Britain, they insist, has not only “always been multicultural”, but ordinary Brits have always been happy with that situation. “Britain”, in their widely disseminated mythology, “has always been tolerant”.

This makes a study of the violent and dismal failure, and rapid and forced reversal, of Britain’s World War One “multiracial experiment” a valuable antidote to modern liberal propaganda. Making policies for the future on the basis of woefully inaccurate accounts of the past is a recipe for disastrous failure.

Britain’s Forgotten Race Riots of 1919

While millions of British men were away fighting and dying on the far-flung battlefields of the First World War, Britain’s main ports saw a growing influx of various non-white ethnicities. These immigrants arrived mainly as seamen, serving on freighters steaming through the German U-boat blockade to keep the country supplied with food and war supplies.

This was a desperately needed part of the war effort. In 1914, only about one-third of the United Kingdom’s food was home-produced. Britain’s agricultural industry had been neglected, and crippled by free trade, since 1870. The bulk of what was needed to avoid starvation had to be imported.

This included key staples like wheat, meat, sugar, and dairy products. For example, around four-fifths of Britain’s wheat and flour were imported, mainly from the United States, Canada, Argentina, and India. Refrigerated ships brought in frozen meat from New Zealand, Australia, and South America, which had become an increasingly important part of the British diet.

Other vital supplies included nitrates from Chile; essential for making explosives; petroleum products, increasingly vital for transport and the Royal Navy, and iron ore, steel, timber and animal fodder.

This dependence made Britain highly vulnerable to the German U-boat campaign. The Battle of the Atlantic of 1917, in which unrestricted submarine warfare sank vast amounts of shipping, came dangerously close to starving Britain into submission. The courage and endurance of the men of the merchant marine fleet was critical to her survival.

Just under 300,000 men and boys served in Britain’s merchant marine. 67% of them were British citizens. Of those who were not, just over half were Lascars. Derived from an Urdu word for an army camp, this entered English via Portuguese and came to mean any sailor, worker or servant recruited from lands east of the Cape of Good Hope. (1)

More an occupational designation than an ethnic one, it broadly covered all non-whites except West Africans, and the West Indians who made up a mere 1% of the fleet’s total crew. These black sailors were generally recorded separately. Men from West Africa were classified as “Kru” or “Kroom”.

The largest contingent among the Lascars, were South Asians, especially from Bengal, Assam, Bombay, Madras, and the Punjab. Many were Muslims from what is now Bangladesh, Pakistan, and northern India, alongside Hindu and Christian Indians. (2)

Next were Arabs, particularly from Yemen, Oman, and the Persian Gulf. Smaller numbers of East Africans, Malays and Chinese were also included.

This was nothing new, Lascars began to be employed to replace dead or deserted British sailors by the East India Company in the 17th century, though the numbers involved were tiny. The entire British navy had just 224 of them at the start of Napoleonic Wars, rising to 1,336 by 1813. More were recruited following the advent of steam engines, as they were thought better able to cope with the intense heat of engine rooms.

On arrival at British ports, they would often have to wait for some considerable time before finding work on an outward-bound ship. Enough of them ended up destitute while waiting for fresh work that Victorian philanthropists (who, as noted by Dickens and many others, had a propensity to worry about non-whites more than the desperate poor among their own kin) established the Strangers’ Home of Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders in West India Dock Road in East London in 1856.

The number of foreign sailors rose rapidly during the war, with up to 50,000 serving in the merchant marine in total.

Some of these men jumped ship and found work on shore, where the sheer number of men already dead or severely disabled in the Forces had indeed created a temporary labour shortage. When the war ended, even more Africans and Lascars quit their vessels with a view to staying in Britain.

“Land Fit for Heroes”

This coincided with the demobilisation of millions of British servicemen. Tensions rose rapidly as men returned home to find immigrants living in their areas. Local housing shortages, the criminal activities of some of the newcomers, and the sight of black men together with white women created huge resentment. This was not the welcome in the “Land Fit for Heroes” the survivors of the terrible conflict had been promised.

The first demobilised British soldiers began returning from France almost immediately after the Armistice on 11th November 1918. Large-scale demobilisation began in December, with many home by Christmas.

Despite black sailors having been very much the minority among the non-British crews, their presence in Britain rapidly caused particular problems.

Scuffles between ex-servicemen and African and West Indian immigrants began almost immediately. As demobilisation accelerated in early 1919, the clashes escalated into full-scale race riots.

On 23rd January 1919, tensions escalated when a fight broke out between white and black sailors in the Broomielaw area, near the River Clyde. The spark was economic, with the local men complaining that black sailors were “being given the preference in signing on for a ship about to sail”, allegedly because they had accepted lower wages to do so. The violence began with a scuffle outside the Mercantile Marine Office, where seamen went to find work.

Thirty African sailors were chased through the streets of Glasgow by a crowd of hundreds, with the Dundee Evening Telegraph reporting that one black sailor had shot and injured a white seaman, one of three injuries sustained during the riot.[3]

The article describes how a black sailor ‘fired a revolver’, injuring a white seamen from Glasgow in the neck. This incensed the crowd even further; with the white contingent ‘charging’ at the black seaman’s group, who took refuge ‘in a close leading to a lodging-house’ where they lived.

The white mob were armed, according to the report; some with revolvers, others with bottles and stones. These latter weapons were thrown at the retreating black sailors, and also at the windows of the lodging house.

A mob of white dockworkers and ex-servicemen began attacking black residents and sailors over a wider area, and the blacks responded with equal ferocity. Seven nights of rioting followed. The police largely sided with the locals, arresting dozens of immigrants and a smaller number of Scots.

Other immigrants were also resented. In February 1919 a major riot broke out in South Shields, a port on the north-east coast of England, where clashes erupted between white and Arab sailors, leading to violent confrontations and widespread property damage.

Shields had a large Yemeni and Somali population. A now forgotten incident led to mobs of locals attacking Arab-owned lodging houses near the docks.

The police arrested dozens of Arab men, but few white rioters faced consequences. Similar disturbances occurred in the nearby ports of Newcastle and Middlesbrough, where African, Arab, and South Asian communities all became targets.

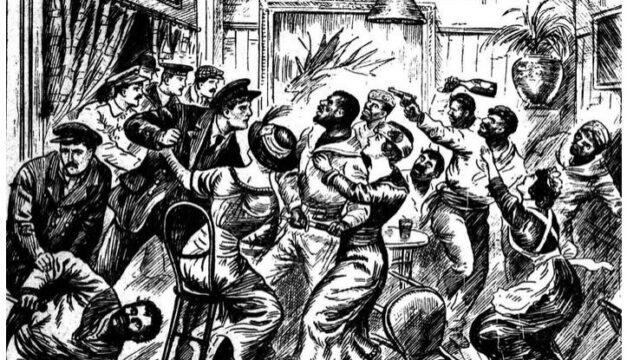

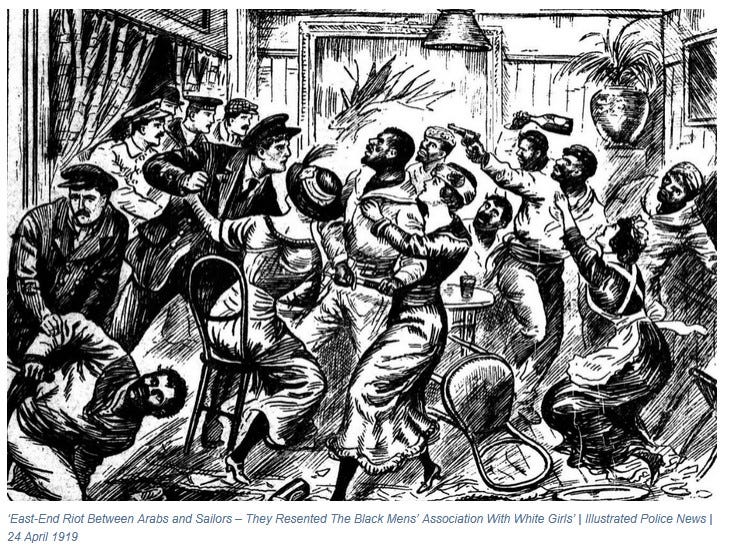

Trouble had already broken out in East London, which saw sporadic riots from January right through to August. The month of April saw a particularly serious disturbance in Cable Street, later to be the scene of the infamous anti-police riot by Communists and Jewish immigrants opposing Sir Oswald Mosley and his Blackshirts.

The 1919 violence began when a shop in Cable Street was attacked by a crowd of 3,000 people. The shop, which was “kept by an Arab”, was targeted after word went round that “some white girls had been seen to enter the house”. (4) The occupants were escorted away from the property by police for their own safety. Official collaboration with grooming gangs is not, perhaps, something unique to modern Britain.

A weeks later, rioting broke out in neighbouring Limehouse, a district with a sizeable Chinese community. Clearly the tensions and troubles involved indigenous resentment against immigrants and immigration in general, rather than merely being a reaction to the criminal behaviour for which the Africans were particularly noted.

Chinese sailors and businesses were also attacked in Hull, when rioting flared up in the main Yorkshire port in May. Most of the violence there was between locals and black seamen, The local press highlighted the fact that, in addition to competition for work and housing, sexual relationships between black men and white women were also deeply resented.

There were reports of mobs attacking black boarding houses and individuals in the street. The police response was notably biased; in the initial disturbances they only arrested black men despite the violence supposedly being instigated by white crowds. Four black men were arrested, including one for possessing an unlicensed revolver.

Tensions had been running high in Liverpool for months. Earlier in the year the Lord Mayor had received a delegation claiming to represent 5,000 unemployed white ex-servicemen and seafarers complaining of competition from black workers.

The Liverpool riots started on June 4th, 1919, when a West Indian named John Johnson was stabbed by two Scandinavian sailors, allegedly after he refused to give them a cigarette.

The next night a fight broke out at the Liverpool Arms pub in ‘Sailortown’ between black seamen and more Scandinavians, leading to further violence all around the docks. Russian sailors were also involved, although the Newcastle Daily Chronicle reported that the trouble had flared after black sailors had attacked a group of Danish seamen. Whoever were the victims, the police responded by raiding boarding houses used by black seamen, which produced a violent immigrant response.

Reporting on the rioting, the London Daily News noted that ‘racial feeling’ had been running ‘high for some time past’. Time and time again, the key issues were described as being rivalry for jobs and the newcomers either going out with or accosting white women. (5) Once the violence began, however, the anger of the mobs was roused mainly by the aggressive self-defence employed by negroes in particular.

One of the most notorious incidents occurred when Charles Wotten, a black 24-year-old and ship’s fireman, was chased by a mob into Queen’s Dock. Despite a police presence, Wotten was thrown into the dock, where he drowned. Fourteen others black men were injured, with five policeman and nine white civilians also hurt.

The deadly attack came after a police constable named Brown was shot in the mouth by one of the black men, ‘the bullet passing through his neck and wounding a sergeant.’ Another police constable was ‘slashed with a razor.’ The modern claim that Wotten’s drowning was an unprovoked racist attack is called into question by the contemporary press report that he was “engaged in the affair” and “taken from the police by the mob”.

The Daily News noted that this outburst of extreme violence only ended when the police were reinforced by ‘civilians and discharged soldiers.’

The Newcastle Daily Chronicle of 7 June 1919 reported on the ‘Serious Liverpool Riot,’ with the headline ‘Mob Drown a Negro.’ The newspaper referred to the ‘exciting and tragic’ scenes in city, which had broken out in ‘the cosmopolitan quarters of Liverpool,’ where the minority ethnic ‘population [had] rapidly increased.’

Over the next few days, mob violence continued, with black homes and boarding houses being ransacked, set on fire, or vandalised. The riots saw angry crowds of up to 10,000 people attacking black men, their families, and rented homes. The Elder Dempster Shipping Line’s hostel for West African sailors and the David Lewis Hostel for black sailors were attacked and many houses were targeted and set alight.

The police were initially overwhelmed and sometimes complicit or ineffective in stopping the violence. They attempted to protect black residents by moving them to police stations for safety, but the scale of the riots made this difficult.

But like the aftermath witnessed in Glasgow, the Newcastle Daily Chronicle recorded that it was thirteen black men ‘who were charged with having attempted to murder three police officers and with having riotously assembled’. The men, most of whom were bandaged, were remanded at Liverpool Police Court.

Given the close ties between Liverpool and Belfast, it was perhaps inevitable that similar troubles would break out in the dock areas of Protestant East Belfast. The city saw nearly a week of violence between angry locals, including many ex-servicemen, and black and Arab seamen, from June 8th to 14th.

South Wales Explosion

As the violence subsided in Liverpool, it spread to South Wales, where the trouble was particularly intense.

On 8 June 1919 the Sunday Pictorial reported on ‘fierce racial riots’ in Newport, Wales. It noted that the outbreak of violence had been fuelled due to relationships between black men and ‘the white girls.’

The Sunday Pictorial related how:

‘The affray started on Friday night with an altercation, in which blows were struck. A large crowd gathered and the negroes retreated to two houses where they live in George-street. Later the coloured men ventured out, and this was the signal for the renewal of the fight. A revolver was fired, and when a number of negroes armed with sticks, pokers, etc., appeared the riot became general.’

‘A baton charge’ was then made by the police, but it was too late to stop the damage to three streets in Newport. The same article describes how:

‘All the windows were smashed, the houses were forced, and all the furniture smashed to atoms. Chinese, Greek and other foreign boarding houses were attacked.’

The Sheffield Independent on 14 June 1919 reported how furniture ‘was burnt in the streets of Newport’, with shops and restaurants also being ‘wrecked’.

Rioting next broke out in Barry on June 11th, after Frederick Longman, a thirty-year-old Western Front veteran, was stabbed to death in the South Wales coal and steel port.

Fred was killed by Charles Emmanuel, originally from the French West Indies. The news that an ex-serviceman had been slain by an immigrant turned existing tensions to fury. As violence escalated in Barry, Cardiff also exploded the same evening.

Cardiff had a sizeable number of Black and Arab (mainly Yemeni) sailors, with a total population of around 700 in the 1911 census. That had grown substantially by the end of the war. “We went to France and when we came back foreigners have got our jobs and we can’t get rid of them,” complained one unemployed former soldier in Cardiff. This was in July 1919, when 1,300 of Cardiff’s of 2,000 registered unemployed were demobilised troops. (6)

A fight broke out in a pub in Cardiff’s dockland between a group of local ex-servicemen and black men. The violence quickly escalated into mob attacks, with white crowds targeting black homes, boarding houses, and businesses in Butetown and Tiger Bay, where the immigrant presence was particularly well established.

One black man who lived through the riots and went on to stay in Wales wrote of the marauding crowds that:

‘The mobsters didn’t get things all their own way. Some of them were badly cut up; negroes started carrying guns and razors to defend themselves. More mobsters got hurt in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay than any other part of Britain, for Tiger Bay had the toughest negroes there were in Britain.’ (7)

The ‘wild colour riots,’ featured in the Belfast Telegraph on 13 June 1919. Again, ‘familiarity between white women’ and black men was identified as the cause of the ‘race riot,’ which had broken out in Bute Town.

The Belfast Telegraph, drawing on a report from national newspaper the Daily Express, describes how the violence started when a black man began ‘firing on the police’. This ‘infuriated’ the white members of the crowd, ‘who attacked the negroes and hunted them for hours’. ‘Free shooting’ was then witnessed in the Welsh city, with ‘volleys’ being ‘fired in the street and from houses’.

The Globe reports that a house on Millicent Street was home to ‘a man of colour,’ who was said to have ‘threatened a woman’. The house was besieged by the mob, and then:

‘The inmates, in a state of panic, commenced shooting, and the mob retaliated with stones and ginger beer bottles. John Donovan, aged 47, a discharged soldier, wearing the Mons ribbon, was shot through the heart and he died after removal to hospital.’

Only then did the police intervene, The Globe describing how:

‘The police came up and entered the house, one receiving a shot through the helmet and another a bullet through his cape, while others sustained slight injuries from stones. They arrested the occupants, one of whom, in the melee, received a severe blow on the head. This man was at first reported dead, but inquiry elicited information that he is lying in a precarious condition in King Edward Hospital.’

As all the tensions boiled over, black men armed themselves and the police, overwhelmed by the scale of the violence, struggled to restore order. The city faced anarchy and, to support his request for urgent assistance, the Cardiff Chief Constable sent a report to the Under Secretary of State at the Home Office on 13 June 1919. This related how the latest violence had led to 21 arrests

‘comprising 16 coloured men for shooting; one coloured man for possessing firearms; and 4 Britishers for wilful damage. The casualties were approximately 12 in number; two proved fatal (one white and one coloured man) 3 coloured men have fractured skulls; one white man fractured skull; and the others were minor injuries.

It is not possible for me to estimate in figures the damage that has been caused.

So far this day, Friday, has gone there is a certain liveliness amongst the white population in and abutting upon [next to] the affected area. It may develop during the evening but I have increased the mounted police on duty to 12 in number and am practically concentrating all my Force in the area of Butetown which is approximately a mile long by 300 yards wide.

There can be no doubt that the aggressors have been those belonging to the white race. To go fully into the probable cause of their attitude would open up many issues but briefly it might safely be said that racial feeling which now exists is due to the following: –

The coloured men resent their inability to secure employment on ships since the Armistice as they are being displaced by white crews;

They are dissatisfied with the action of the Government;

They regard themselves as British subjects;

They claim equal treatment with whites and contend that they fought for the British Empire during the war and manned their food ships during the submarine campaign.

The white population appear to be alarmed at the association of so many white women with the coloured races and imagine that they entice the white women to their houses. (As a matter of fact so far as the Police can observe certain white women court the favour of the coloured races).

The housing question also arises. The coloured men have earned good wages during the war; they have saved their money; they have purchased houses; are always willing to pay higher rents; and even exorbitant [very high] sums as “key money” to secure possessions of dwelling houses or shop premises. This feature particularly irritates the demobilized soldiers who have been unable to secure housing accommodation., (8)

After three days and nights of rioting, and the deaths of three black men, the army was called in. Not surprisingly, serving soldiers tended to sympathise with their demobilised former comrades, so black men were disproportionately among those arrested.

Modern accounts of the troubles predictably cast the indigenous Welsh as the racist villains, and accuse the British state of a racist response. One of the few hard facts still available, however, is that Charles Emmanuel, who had stabbed Fred Longman to death, was found not guilty of murder and jailed for just five years for manslaughter – hardly a kangaroo court!

In the course of the riots, police arrested nearly twice as many blacks (155) as whites (89). While most of the whites were convicted, however, nearly half of Black arrestees were acquitted. The leftist interpretation of this disparity is that the courts were acknowledging their innocence and were recognising and attempting to correct police bias.[9)

Those familiar with the two-tier policing notorious in modern Britain may reach a different conclusion, seeing anti-white bias among the ruling elite as having long and deep roots. It is clear from various cases that many of the immigrants who had been “arrested” were in fact taken away by the police for their own protection, with charges against them later dropped or rejected by the courts.

The British public of 1919, however, most certainly did not share officialdoms’ sympathy for immigrants. Mid-June also saw several nights of rioting in Salford, where foreign workers in the Manchester Ship Canal dockyard were accused of helping the bosses to lower wages. Locals complained bitterly that the newcomers were taking jobs which should have gone to ex-soldiers, who were unemployed following demobilisation.

This was a common thread in all the disturbances; working class communities in a nation which had lost 880,000 men in the “Great War” were understandably bitter at the way surviving heroes were being thrown on the scrapheap in favour of cheap foreign labour.

Repatriation Efforts

Even before the widespread disorder of June 1919, the British government had begun a formal effort to deport or repatriate colonial citizens. This started in February 1919, but this was stepped up immediately after the June riots.

The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette on 17 June 1919 reported how a special court was held in the city to ‘deal with cases arising out of the racial riots,’ which saw 65 people in total in custody. The newspaper details how fourteen of the Black arrestees were remanded, ‘charged with attempting to murder three policemen and rioting.’

The short piece in the Devon newspaper ended by noting that: ‘A hundred West Africans are to be taken home from Liverpool this week by the Elder Dempster Line’.

The Daily News of 18 June 1919 followed up with the revelation that the British Government were going to do ‘all in their power to repatriate’ those involved in the riots, ‘so as to relieve the situation caused at Liverpool and Cardiff by the racial riots.’

The paper went on to relate how the Ministry of Shipping was organising ‘repatriation efforts,’ although they had encountered ‘great difficulty’ in providing ‘shipping for the purpose.’

Meanwhile, the newspaper put the figure at 200 passengers instead of the 100 outlined by the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, dubbing the move as an ‘experiment.’ Should it ‘prove successful,’ another steamer would be sent from Liverpool to West Africa. Another ship was set to be arranged for those with a ‘desire to return to the West Indies at the end of the month.’

On 13 September the same year, the Bristol Times and Mirror noted that 600 ‘blackmen have been sent from Bristol Channel ports to their homes overseas.’

Between 1919 and 1921, an estimated 3,000 black and Arab seamen, and their families, were removed from Britain under a repatriation scheme. This included a resettlement allowance of £2 to £5, plus an additional £5 on disembarkation. (10) Others simply signed onto the next available ship home.

How many stayed despite the riots and resettlement scheme is unclear. Small clusters of streets in places such as Tiger Bay in Cardiff, Limehouse in London and Toxteth in Liverpool continued to be noted as immigrant and mixed-race enclaves.

In general, however, the violent reaction to multiculturalism and its discontents in 1919, and the subsequent measures to reverse the tide of immigration, meant that those who wanted to change the face of Britain had to wait another thirty years before making their move.

The immigration wave which had begun during World War One was halted. Contrary to some claims, this was not due to the Depression. Indeed, 1919 and 1920 saw an economic boom in Britain, fuelled by pent-up investment pouring into civilian projects and the race to replace warships and merchant vessels lost during the war due to ship building.

This petered out towards the end of 1921, but immigration had been stopped dead two years before; not by changing economic circumstances, but due to rough but ready popular direct action against it.

FOOTNOTES

1 Butalia, Romesh C (1999), The evolution of the Artillery in India, Allied Publishers, p. 239, ISBN 978-81-7023-872-0

2 https://www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/the-lascars-britains-colonial-era-sailors

3 Dundee Evening Telegraph on 24 January 1919

4 Staveley-Wadham, Rose (26 October 2022). “1919 Race Riots”. The British Newspaper Archive Blog. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

5 Daily News 6 June 1919

6 https://www.ourhistory.org.uk/1919-race-riots/ Accessed 10 Sept 2025

7 Ernest Marke In Troubled Waters: Memoirs of Seventy Years in England (London: Karia Press, 1986).

8 https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/1919-race-riots/

9 Jenkinson, Jacqueline (2009). Black 1919: Riots, Racism and Resistance in Imperial Britain. Liverpool University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt5vjd9g.10. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

10 https://blackpast.org/global-african-history/britain-s-1919-race-riots Retrieved 10 Sept 2025

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bourne, S.: ‘Liverpool and the Murder of Charles Wotten’ in Black Poppies : Britain’s Black Community and The Great War (Stroud: The History Press, 2014) pp. 147-152.

Hood, W. H.: The Blight of Insubordination: the Lascar Question and Rights and Wrongs of the British Shipmaster. (London: Spottiswoode & Co., 1903). Wikidata Q118286993

Jenkinson, J.: ‘The 1919 Race Riots in Britain: A Survey’ in Rainer, L. & Pegg, I. (eds): Under the Imperial Carpet: Essays in Black History, 1780-1950 (Crawley: Rabbit Press, 1986.).

Marke, E.: In Troubled Waters: Memoirs of Seventy Years in England (London: Karia Press,1986). ISBN: 9780946918324

Salter, Joseph.: The Asiatic in England: Sketches of Sixteen Years’ Work Among Orientals. Franklin Classics

https://nickgriffin544956.substack.com/p/britains-forgotten-race-riots-of