Bullet Train Boondoggle

California has always done things in a big way, beginning with becoming a state in the Union without first going through the territorial process, because of the Gold Rush. Until recently, most of the things California did in a big way were wildly successful and the envy of other states and even of foreign nations.

Those of us who grew up in the immediate post-World War II era were California chauvinists. We thought California had it all—and in that era, it mostly did. Evidently, Americans from other states felt the same way, flooding into the Golden State by the tens of thousands every year. In 1945, the state had a population of 9 million. By 1964, the population had doubled to 18 million. In response, California built dams and aqueducts, highways, airports, marinas, parks, schools, and universities with astounding speed. California was, indeed, golden.

Today the state continues to do things in a big way—but now there are also big fails. The biggest fail of them all is the High-Speed Rail project, more commonly called the Bullet Train, first proposed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 1979. Called Governor Moonbeam by Chicago columnist Mike Royko, Brown was an eccentric character who, at one time, was in seminary training to become a Catholic priest and, later, seemingly on his way to becoming a Buddhist monk. Brown’s moonbeam reputation, however, obscured the fact that he was, above all, a crafty and savvy politician who could become whatever he needed to be to win elections. And win elections he did: California secretary of state in 1970; governor in 1974 and 1978, and again in 2010 and 2014; mayor of Oakland, 1998 and 2002; and attorney general, 2006.

There could have been no better promoter of high-speed rail than Jerry Brown. For him it was an environmental and social issue. He wanted to get cars off the roads, thinking people should use public transportation. He saw Western Europe and Japan as examples to be emulated. He promoted the bullet train to the public as a quick and economical way to travel between Los Angeles and San Francisco. No airport hassles and expense and no six-hour drive on the boring Interstate 5 or eight-hour drive on the more scenic Coast Highway. Climb aboard the bullet train, relax in plush seats, enjoy five-star dining, and be in San Francisco in two hours.

The vision was dazzling and it had bipartisan support. There were politicians who were fans of the high-speed trains in Japan and France and also politicians who saw it as a gravy train. There were also unions who thought of the thousands of construction jobs that would come with the project. Brown did his best to get something rolling during the last two years of his second term as governor, even proposing coordinating the project with Japanese partners, but because of funding issues and environmental concerns, nothing got started.

With Brown out of office, the proposed project languished until 1993 when the state formed the Intercity High-Speed Rail Commission, followed by the passage of the High-Speed Rail Act that authorized the creation of the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) to design, construct, and operate a high-speed railroad. We now had a Commission and an Authority. The bureaucracy was growing—and this was under moderately conservative Gov. Pete Wilson. Funding still remained a problem, especially because, by the 1990s, California’s infrastructure was facing severe strains from illegal immigration.

Let’s be optimistic and say there will be a “bullet train” connecting L.A. and San Francisco by 2040. That’s 25 years of construction, six times longer than it took to build the transcontinental railroad connecting Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento, California, in the 1860s. Of course, all the transcontinental line had to do back then was cross the Great Plains, the Rockies, the Great Basin, and the Sierras, a mere 1,800 miles of the still wild American West.

The project again stalled but was given new life in 2008, when the state legislature put Proposition 1A on the ballot. The proposition authorized funding through $9 billion in bonds and another $950 million for commuter rail systems that connected with the bullet train. The proposition also required that any state expenditures be matched by federal funds.

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who had been voted into office as a fiscal conservative and initially made some attempts at restraining reckless spending, was now going along to get along and supported the proposition. Both the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce and the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce were supporters, as were most Democrats and unions. True fiscal conservatives, such as state assemblyman Chuck Devore and state senators Tom McClintock and George Runner, were vocal opponents. Not surprisingly, they were joined by Jon Coupal of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association. Moreover, by 2008 a good chunk of the general public had become suspicious of the hyperbolic promises made by promoters of the train and of the low-ball estimates for construction and operation. Nonetheless, Proposition 1A passed with 52.6 percent of the vote.

By the time ground was broken in 2015 it had been decided that the bullet train would not go up the scenic coast route to San Francisco but through the flat farmlands of the San Joaquin Valley, roughly paralleling Highway 99. Anyone who has driven the 99 through the valley knows laying track there wouldn’t seem to be much of a problem. Although that stretch was designated as the first to be built, here we are 10 years later and not one mile of track has been laid. The High-Speed Rail Authority brags that “since the start of high-speed rail construction, the project has created more than 15,300 good paying construction jobs, a majority going to residents of the Central Valley.” Meanwhile, billions of dollars have been spent. The gravy train.

Until President Trump’s first term in office, the billions of dollars spent by California on the “train to nowhere” had been matched by the federal government, demonstrating the power of the large California congressional delegation and the inertia of a great boondoggle once begun. In May 2019, the Trump administration announced that nearly $1 billion not yet paid by the federal government would be withheld because the High-Speed Rail Authority had missed every deadline imposed on it by the funding agreement. Moreover, in another violation of the agreement, the authority had abandoned the goal of connecting Los Angeles and San Francisco and was now intent only on connecting Bakersfield and Merced in the San Joaquin Valley. With President Biden in office, however, federal funding began again—a $3.1 billion dollar flow of gravy, making for a total of nearly $7 billion of federal money spent on the project since 2009.

That’s now ending. In February 2025, President Trump called for an audit of the project. In June, Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy released a highly detailed and critical report on the project. Said Secretary Duffy:

I promised the American people we would be good stewards of their hard-earned tax dollars. This report exposes a cold, hard truth: CHSRA has no viable path to complete this project on time or on budget. CHSRA is on notice—if they can’t deliver on their end of the deal, it could be time for these funds to flow to other projects that can achieve President Trump’s vision of building great, big, beautiful things again. Our country deserves high-speed rail that makes us proud—not boondoggle trains to nowhere.

In July, Duffy announced that $4 billion in unspent funding allocated for the project by the Federal Railroad Administration was canceled. Moreover, he suggested the federal government could even demand the return of the nearly $7 billion of federal funds California has already used because the High-Speed Rail Authority failed to met the requirements of the original funding agreement.

California is now scrambling to come up with a funding plan. It’s estimated that it will cost another $14 billion to complete only the San Joaquin Valley portion of the line. In 2008, when the Proposition 1A bond measure was being debated, the High-Speed Rail Authority estimated construction would cost $33 billion for a line from Los Angeles to San Francisco and that it would be in operation by 2028. Now, the CHRSA is saying the San Joaquin portion won’t be finished until the early 2030s and that the original goal of connecting L.A. and San Francisco will extend into the late 2030s or early 2040s. The cost estimate for full completion is now $135 billion. Critics say it could be double that.

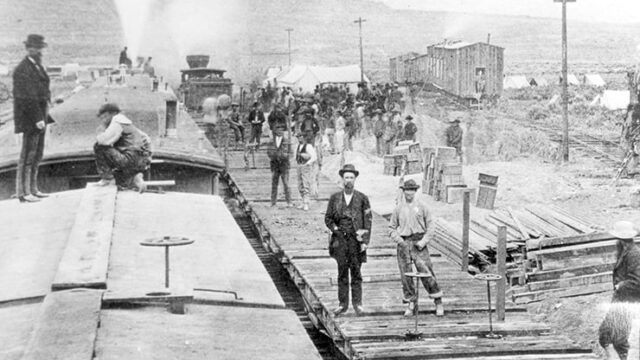

Let’s be optimistic and say there will be a “bullet train” connecting L.A. and San Francisco by 2040. That’s 25 years of construction, six times longer than it took to build the Transcontinental Railroad connecting Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento, California, in the 1860s. Of course, all the transcontinental line had to do back then was cross the Great Plains, the Rockies, the Great Basin, and the Sierras, a mere 1,800 miles of the still wild American West. And the workers built it using mostly hand tools, while facing blizzards, scorching heat, and Indian attacks.

Track laying for the Transcontinental Railroad didn’t begin until several months after the Civil War ended and was completed by May 1869. For those running the California High-Speed Rail Authority: That’s just four years. Moreover, two private companies did it. The Union Pacific Railroad built westward from Omaha and the Central Pacific Railroad eastward from Sacramento. The federal government didn’t pour money into the project but instead granted each company alternate sections of federal land for each mile of track laid along the route. This proved a highly effective incentive. Each company spurred its men on relentlessly, hoping for a greater share of that bounty in land. It became a great race in different directions across the continent.

One day in the spring of 1869 the Union Pacific laid an astounding six miles of track and invited the Central Pacific to match it. The Central Pacific came back with seven miles in a day. The Union Pacific countered with seven and a half miles. Charles Crocker of the CP said his boys would better that, too. Thomas Durant of the Union Pacific bet him $10,000—something like $1 million today—that the Central Pacific couldn’t do it.

Crocker waited until the two lines were approaching a last-minute congressionally designated meeting point at Promontory Summit before attempting to break the Union Pacific’s record. He didn’t want to leave enough room for the Union Pacific to respond should the Central Pacific lay more than seven and a half miles of track.

Early on the morning of April 28, Central Pacific crew chief George Coley assembled eight of his brawniest men to lay the track. With reporters from the Chicago Tribune and Daily Alta California watching and timing, the track layers swung into action. Each rail was 30 feet long and weighed 560 pounds. Two men using tongs grabbed the front of the rail with two men following with the rear end. Four men were doing the same thing on the other side of the track. Although they were hefting hundreds of pounds, they moved at a walking pace. “I timed the movement twice,” said a reporter from the Daily Alta California. “The first time 240 feet of rail was laid in one minute and twenty seconds; the second time 240 feet in one minute and 15 seconds.” The men maintained the pace hour after hour, without pause.

By 1:30 in the afternoon, after having laid an incredible six miles of track, the men took a break for dinner. They were asked if they wanted to be replaced by a fresh crew. Emphatically and pugnaciously, they said no. After eating and resting, they started again, but soon the grade steepened and curved into the hills. They now were delayed an hour to bend rails for the curves before they could return to laying the tracks. The grade slowed their pace but they kept lifting, hauling, and dropping the 560-pound rails in place. At 7:00 in the evening work was halted. The men had laid 10 miles and 56 feet of rail. That amounted to some 3,500 rails with a total weight of 1.96 million pounds. Since two hours were lost in dinner and bending rails, this meant the men were moving 196,000 pounds of iron per hour for 10 hours. Arnold Schwarzeneggar, eat your heart out.

“It may seem incredible, but nevertheless it is a fact that the whole ten miles of rail were handled and laid down this day by eight white men,” a reporter from the Daily Alta California wrote. “These men were Michael Shea, Michael Kennedy, Michael Sullivan, Patrick Joyce, Thomas Daley, George Elliot, Edward Killeen, and Fred McNamara. These eight Irishmen in one day handled more than 3,500 rails—1,000 tons of iron.”

The Irish lads were paid four days wages for their effort and Charles Crocker pocketed $10,000.

Here we are a century and a half later, and California can’t seem to build a train from Bakersfield to Modesto, let alone from Los Angeles to San Francisco. Between Bakersfield and Modesto is 200 miles of flat land. Shea, McNamara, and the others could have laid the necessary track in 20 days. It may take the bullet train boondoggle 20 years to do the same. ◆

https://chroniclesmagazine.org/columns/bullet-train-boondoggle