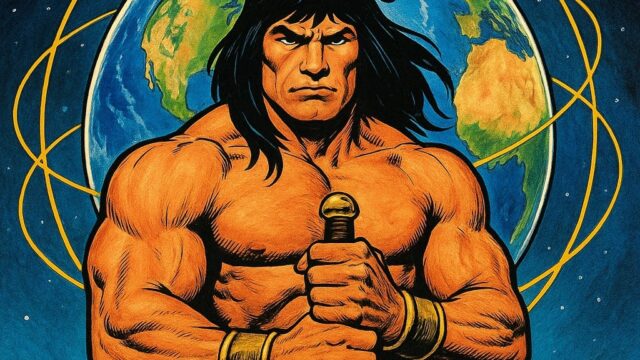

Conan and Multipolarity

Conan walks the shifting map of the Hyborian Age as a free blade in a world of many thrones, proving that strength, clarity, and will decide the fate of empires.

Conan strides into the realm of multipolarity as a figure drawn from the deep well of heroic myth and yet sharpened by the dust and steel of lived experience. Born in Cimmeria, a land of grey skies and grim hills, he enters a world fractured into dozens of kingdoms, empires, and tribes, each with its own gods, languages, and codes. From the streets of Zamora where he plies the thief’s craft, scaling towers under the moonlight to wrest jewels from under the noses of corrupt sorcerers, to the blood-soaked battlefields where he serves as a mercenary in Turan or Koth, Conan’s path unfolds across a continent where no single power holds the leash of destiny. The Hyborian Age is not a monolith but a mosaic, each shard glittering with its own ambition, and Conan thrives in this space because he does not pledge his soul to any one throne. His allegiance is shaped by opportunity and honor as he understands it, making him both participant in and symbol of a world where multiple centers of power wrestle without a supreme master.

The Hyborian world itself is the clearest mirror of multipolarity. Aquilonia’s mailed knights guard their fertile western plains while Nemedia’s courts scheme in opulent marble halls; the Stygians brood along the Nile-like Styx under the shadow of their ancient temples; the eastern kingdoms of Turan reach across deserts towards the riches of the west. These realms do not speak with one voice, and their rivalries give birth to wars, treaties, betrayals, and shifting alliances. In “The Black Colossus,” Conan rises from mercenary captain to commander of Khoraja’s army in a single night because a queen sees in him the strength to resist a sorcerer’s invasion. This is how power moves in a multipolar age: through sudden shifts, through leaders who prove themselves in the moment, through the collapse of one order and the swift rise of another. Conan is not a fixed instrument of any state but a free blade whose loyalty is earned anew with each cause, much as smaller powers in a multipolar system weigh their commitments against the needs of survival.

His nature is to see through illusions, for in a world where a silver tongue can be as deadly as a dagger, a man must weigh words against deeds. When he enters the jeweled courts of Ophir or Nemedia, he knows that the soft-spoken nobles measure life in intrigues, yet he refuses to be dazzled by their silks or cowed by their ranks. In “The Scarlet Citadel,” betrayed and cast into a dungeon after losing a battle, Conan escapes not through fine speeches but by brute strength and unshakable will, returning to claim his throne in Aquilonia. Multipolarity rewards this clarity of vision: seeing that treaties mean little unless backed by strength, that alliances last only as long as interests align. Conan’s instinct to act on reality rather than rhetoric is the same instinct a state must cultivate in a world where every capital guards its own designs.

His travels bring him into contact with cultures as varied as the snowbound tribes of the north and the desert horsemen of the south. In “Queen of the Black Coast,” he joins Bêlit, the Shemite pirate queen, and together they sail the black waters of Kush, plundering coastal towns and ruling the sea by force of arms. Their bond is forged in battle and dissolved only by death, and Conan mourns her with the same intensity that he once fought beside her. In multipolar terms, this is the essence of temporary alignment: fierce cooperation in pursuit of shared aims, without the illusion that such bonds exist for eternity. Civilizations too can share ventures, trade, and victories without surrendering their identity to an overarching authority, just as Conan’s partnerships end when their shared purpose is fulfilled.

The lands through which Conan moves are bound together not by a single vision of life but by the practical reality of contact: trade, war, and migration. Stygia’s ancient priesthood wields sorcery that terrifies the west; the black kingdoms guard their own mysteries; the Picts in the wilderness raid Aquilonia’s frontier without thought of diplomacy. Conan can shift from one world to another because he does not demand that they conform to his way. In “The Tower of the Elephant,” he listens to the strange tale of Yag-Kosha, a being from beyond the stars, and his response is not to question the alien’s reality but to act on the truth before him. Multipolarity depends on such an instinct: to engage with the foreign on its own terms while securing one’s own position.

Change is the rhythm of the Hyborian Age. In “The Hour of the Dragon,” Conan is king of Aquilonia yet finds himself overthrown by a coalition of enemies who summon an ancient sorcerer to destroy him. Stripped of his throne, he crosses half a continent to reclaim it, forging alliances with those who once opposed him and cutting down those who stand in his path. States in a multipolar order must live with this same reality. Today’s ally may be tomorrow’s foe, and yesterday’s enemy may hold the key to survival. Conan’s readiness to adapt without losing the core of his purpose allows him to recover from reversals that would break lesser men.

His kingship in Aquilonia, hard-won and fiercely defended, shows the shape of authority in a multipolar frame. He rules as a man among men, visible to his soldiers, feared by his enemies, and respected by those who know his record. In court, he favors direct counsel over flattery, for he has seen too much of the world to mistake words for steel. His reign is sustained not by a distant imperial order but by his personal ability to meet threats as they arise, to hold his kingdom’s borders, and to rally his people. In the absence of a universal arbiter, this is the kind of sovereignty that endures.

Conan remains a living emblem of a world without a single center, a figure whose power grows from his independence and whose path moves through the cracks of larger powers. In every story, he meets the truth that in a world of many poles, strength comes from readiness, clarity, and the will to act without waiting for approval. His sword cuts through the fog of politics as easily as it cuts through mail and bone, and his mind measures worth by action rather than title. For readers and for nations, Conan’s life is a reminder that the world does not belong to the most refined theories but to those who can master both the harshness of reality and the opportunities it offers.