Control, Crisis and Compliance: Endgame Logic of Late Capitalism

It must be made clear from the start that, drawing on the work of sociologist Max Weber, capitalism is an ‘ideal type’ concept. An ideal type is a conceptual tool that highlights certain key characteristics of a phenomenon by accentuating some elements while omitting others. It is not meant to perfectly correspond to any specific real-world instance but serves as a construct to analyse and compare social or economic phenomena.

This framing is critical: while capitalism is often described as a system of free markets and voluntary exchange, in reality, it frequently relies on collusion, corruption and state-corporate coercion and violence. Having stated this, as an economic system, capitalism inherently requires constant growth, expanding markets and sufficient demand to sustain profitability.

However, as markets saturate and demand falls, overproduction and overaccumulation of capital become systemic problems, leading to economic crises. When capital cannot be reinvested profitably due to declining demand or lack of new markets, wealth accumulates excessively, devalues and triggers crises. This tendency is linked to a long-term decline in the capitalist rate of profit, which has fallen significantly since the 19th century.

Neoliberalism’s playbook

Capitalism in the form of neoliberal globalisation since the 1980s has responded to these crises by expanding credit markets and increasing personal debt to maintain consumer demand as workers’ wages are squeezed or they are made unemployed.

Other strategies have also been deployed. These include financial and real estate speculation, stock buybacks, massive bailouts, public asset selloffs, regulatory ‘reform’ and subsidies using public money to sustain private capital and boosting militarism, which drives demand in many sectors of the economy (one reason why Germany and other European countries are following in the footsteps of the US by boosting their spending on militarism and creating bogeymen as a justification).

These financial manoeuvres are not isolated tactics but part of a broader neoliberal agenda that also involves deregulating international capital flows and exposure to global capital markets, resulting in the obsession of maintaining ‘market confidence’ to hedge against capital flight and surrendering economic sovereignty to finance capital. We also see the displacement of production in other countries in order to capture foreign markets.

This global expansion of neoliberal capitalism is a form of imperialism, where powerful corporations and financial interests impose structural adjustments and policies that undermine local economies, especially in the Global South. The capture of new markets abroad is essential for capital accumulation and offsetting potential declining profitability at home.

This imperial dynamic is particularly visible in the agricultural sector. For instance, the process involves the destruction of indigenous rural economies, the imposition of chemical-dependent industrial agriculture and transformation of food systems to benefit global agribusiness oligopolies. Think too of the profit-driven technofixes being rolled out by Big Tech and Big Ag: the ultimate commodification and corporate capture of knowledge, seeds, data and so on under the crisis narrative of impending Malthusian catastrophe.

And this alludes to the fact that capital seeks ideological cover for its financial ambitions. The climate emergency narrative is being used to legitimise new financially lucrative instruments such as carbon trading and green investments, schemes designed to absorb surplus wealth under the guise of environmentalism. This reflects a broader pattern where perceived (or manufactured) crises are exploited to create speculative markets and investment opportunities that maintain capital accumulation.

COVID and Ukraine

This logic reached a new intensity during the COVID event, which provided a stark and recent illustration of how the ongoing crisis of neoliberal capitalism is exploited and managed, serving as a critical phase in its evolution. This event and associated lockdowns amplified structural inequalities and reshaped the dynamics of capital and control.

COVID was used as a strategy of ‘creative destruction’, accelerating the destruction of millions of livelihoods globally and pushing small businesses towards bankruptcy. Rather than providing genuine aid to the public, COVID policies and massive government spending primarily benefited large corporations—boosting their margins while forcing smaller enterprises to the brink and consolidating corporate power.

At the same time, COVID was used to justify unprecedented restrictions on freedoms, increased surveillance and digital control mechanisms. More on this later.

Lockdowns helped reshape capitalist accumulation patterns by externally imposing economic shutdowns that monetary policy alone could not achieve. They created conditions for increased indebtedness for households, small businesses and (Global South) nations, corporate bailouts and the imposition of new forms of control, thereby managing the contradictions of capitalism through non-market means.

According to Prof. Fabio Vighi of Cardiff University, financial markets were already collapsing before lockdowns were imposed; lockdowns did not cause the market crash in early 2022 but were imposed because financial markets were failing. Lockdowns effectively turned off the engine of the economy—suspending business transactions and draining demand for credit—which allowed central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, to flood financial markets with massive emergency monetary injections without triggering hyperinflation in the real economy. Looking at Europe, investigative journalist Michael Byrant says that €1.5 trillion was needed to deal with the financial crisis in Europe alone in 2020.

This strategy was designed to stabilise and restructure the financial architecture by halting the flow of economic activity temporarily, enabling a multi-trillion-dollar bailout of Big Finance and large corporations under the guise of COVID relief. A bailout that dwarfed anything seen during the 2008 financial crisis.

Lockdowns not only destroyed small businesses and accelerated corporate consolidation, but—unlike the 2008 bailouts—this process faced little opposition, as it was justified as a public health necessity.

While COVID marked one phase of crisis management, the subsequent war in Ukraine has further accelerated these dynamics. It has served to redirect flows of energy, finance and industrial capacity. The destruction of Europe’s energy ties with Russia—via sanctions, decoupling and sabotage—engineered a forced dependency on high-cost US liquefied natural gas, delivering record profits to American fossil fuel firms (in 2022 alone, US LNG exports to the EU more than doubled—from 22 to 56 billion cubic metres—making up over half of all US LNG exports).

As European industries faltered under the weight of inflation and energy instability, the US subordinated its allies through enforced dependency while securing new opportunities for accumulation at home. Dollar supremacy was reinforced, compliance internalised and capital relocated under the banner of war. In this scenario, Europe has become both a very junior partner and collateral damage with its economic sovereignty sacrificed on the altar of transatlantic profit realignment.

The state, crisis and control

This brings us to a broader understanding of the state’s role in maintaining the economic system. The state and ideology are crucial for maintaining capitalism’s economic base, with the state intervening through financial support and strategic market expansion. At the same time, ideology shapes public perception and legitimises actions by re-framing individual freedoms and exploiting crises like COVID and Ukraine to manage dissent and uphold elite power.

This ideological reconfiguration aligns with technological transformation. The rise of artificial intelligence and advanced automation technologies—such as robotics, driverless vehicles, 3D printing, drone technology and even ‘farmerless farms’—will reshape the traditional mass labour force that underpins capitalist economic activity: it is being profoundly transformed and, ultimately, significantly reduced.

Looking ahead, as economic activity is restructured through these technologies, the entire social infrastructure built to reproduce labour—mass education, welfare, healthcare—will be rendered increasingly unnecessary because fewer workers are needed to sustain production and services. This transformation alters labour’s classical role as a seller of labour power to capital, fundamentally changing the dynamics of the labour-capital relationship.

The question is: if labour is defined in terms of its relation to capital and is the condition for the existence of the working class, why bother with maintaining or reproducing labour?

In this context of social erosion, neoliberalism has already weakened trade unions, suppressed wages and increased inequality. And now the message is: get used to being poor or on the scrapheap, and dissent will not be tolerated.

From surveillance to subjugation

The so-called ‘Great Reset anticipates a fundamental transformation of Western societies, resulting in permanent restrictions on liberties and mass surveillance.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) has speculated about a future where people ‘rent’ rather than own goods (as seen in the widely circulated ‘you will own nothing and be happy’ video), raising concerns about the erosion of ownership rights under the rhetoric of a ‘green economy’, ‘sustainable consumption’ and ‘climate emergency’.

Climate alarmism and the mantra of sustainability are about promoting money-making schemes. Beyond this, these narratives also serve to cement social control.

Neoliberalism has run its course, resulting in the impoverishment of large sections of the population. But to dampen dissent and lower expectations, the levels of personal freedom we have been used to will not be tolerated. This means that the wider population will be subjected to the discipline of an emerging surveillance state.

To push back against any dissent, ordinary people are being told that they must sacrifice personal liberty in order to protect public health, societal security or the climate. Unlike in the old normal of consumer-oriented neoliberalism, an ideological shift is occurring whereby personal freedoms are increasingly depicted as being dangerous because they run counter to the collective good.

In the 1980s, to help legitimise the deregulation-privatisation neoliberal globalisation agenda, government and media instigated an ideological onslaught, driving home the primacy of ‘free enterprise’, individual rights and responsibility and emphasising a shift away from the role of the ‘nanny state’, trade unions and the collective in society.

We are currently seeing another ideological shift. As in the 1980s, this messaging is being driven by an economic impulse. This time, the collapsing neoliberal project.

The masses are being conditioned to get used to lower living standards and accept them. At the same time, to muddy the waters, the message is that lower living standards are the result of mass immigration or supply shocks that both the Ukraine conflict and ‘the virus’ have caused.

The net-zero carbon emissions agenda will help legitimise lower living standards (reducing your carbon footprint) while reinforcing the notion that our rights must be sacrificed for the greater good. You will own nothing, not because the rich and their neoliberal agenda made you poor, but because you will be instructed to stop being irresponsible and must act to protect the planet.

Decreased consumption (your poverty) will be sold as being good for the planet by coopting the concept of ‘degrowth’; something to be imposed on the masses while elites continue to accumulate. This contrasts with genuine ecological or socialist degrowth proposals that would target elite consumption and redistribute resources.

Meanwhile, the framework is in place to ensure that huge corporations and the super-rich continue to rake in near-record profits through militarism, an energy transition, a food transition, speculative finance schemes involving land, carbon trading, data monetisation, surveillance capital, pharmaceuticals, green bonds, commodities and agribusiness, real estate and climate risk derivatives.

And there is always money available for Ukraine and various destabilisations around the world to further ensure the bottom line of giant corporations.

India as global microcosm

To illustrate global dynamics and the real-world impact of neoliberal policies, we can examine the case of India’s agricultural sector.

Structural adjustment programmes imposed by institutions like the IMF and World Bank or bilateral agreements with the US have forced countries like India to radically transform their agricultural sectors. Subsequent directives have demanded dismantling public support systems such as state-owned seed supply, subsidies and public agricultural institutions, while promoting export-oriented cash crops to earn foreign exchange.

This shift is part of a neoliberal agenda to further integrate agriculture into global capital markets, reduce the role of the public sector and open up the sector to foreign direct investment and multinational agribusiness corporations.

The outcome in India thus far has been devastating for millions of small-scale farmers and rural dwellers. Neoliberal reforms have led to spiralling input costs, dependency on proprietary seeds and agrochemicals and the erosion of traditional farming systems. This has resulted in widespread indebtedness, economic distress and a decline in the number of cultivators—millions have been pushed off the land, many driven to suicide, and hundreds of millions face jobless growth and rural displacement.

This restructuring facilitates the capture of agriculture by large agribusiness corporations and financial investors. These entities dominate global commodity trading and are increasingly consolidating control over seeds, inputs, logistics and retail. The public sector’s role is reduced to a facilitator of private capital, enabling the entrenchment of industrial, GMO-based commodity crop agriculture suited to corporate interests rather than local food security or ecological sustainability.

Contrast this with agroecology, a means to free farmers from dependency on manipulated commodity markets, unfair subsidies and food insecurity. Agroecology prioritises local food sovereignty, ecological sustainability and farmer knowledge, opposing the reductionist, industrial agriculture paradigm promoted by capitalist agribusiness.

In India, the policy of population displacement compels displaced rural workers to migrate to urban areas in search of precarious, low-paid employment or remain unemployed, swelling the ranks of a surplus labour force.

This reserve army of labour is not accidental but serves a strategic function within global capitalism. It helps suppress wages and weaken the bargaining power of workers and trade unions both in India and internationally. By maintaining a large pool of cheap and insecure labour, capital can discipline workers through competition and insecurity.

Moreover, many of these displaced Indian workers are absorbed into offshore factories and global supply chains, effectively acting as a tool to undermine labour rights and conditions in wealthier countries.

This analysis reflects the country’s incorporation into the global capitalist system, where rural displacement and labour ‘flexibility’ are central to maintaining capitalist dynamics.

There is a historical comparison to be made between the displacement of people from the land in England during the Industrial Revolution and the contemporary displacement of the peasantry in India under neoliberal capitalism. Just as the enclosure movement in England forcibly removed peasants from their land, pushing them into cities to become a labour force for emerging industrial capitalism, a similar process is unfolding in India today.

Benign language

This displacement is not simply a byproduct of ‘development’ but a deliberate process tied to capitalist accumulation and imperialist restructuring of agriculture, where local food systems and rural livelihoods are subordinated to corporate interests and global markets.

Global communications and business strategy company APCO Worldwide is a lobby agency with firm links to the Wall Street/corporate US establishment and facilitates its global agenda. Some years ago, following the 2008 financial crisis, APCO stated that India’s resilience in weathering the global downturn has made governments, policy makers, economists, corporate houses and fund managers believe that the country can play a significant role in the recovery of global capitalism.

Decoded, this means global capital moving into secure control of markets. Where agriculture is concerned, this hides behind emotive and seemingly altruistic rhetoric about ‘helping farmers’ and the need to ‘feed a burgeoning population’ (regardless of the fact this is exactly what India’s farmers have been doing). APCO talks about positioning international funds and facilitating corporations’ ability to exploit markets, sell products and secure profit.

And the state has been actively obliging. The plan is to displace the peasantry, create a land market and amalgamate landholdings to form larger farms that are more suited to international land investors and export-oriented industrial farming.

For instance, an MoU was entered into by the Indian government in April 2021 with Microsoft, allowing its local partner, CropData, to leverage a master database of farmers. CropData was to be granted access to a government database of 50 million farmers and their land records. As the database is developed, it will include farmers’ personal details, profiles of land held, production information and financial details.

The stated aim is to use digital technology to improve financing, inputs, cultivation and supply and distribution. The unstated aims are to impose a certain model of farming, promote profitable corporate technologies and products, encourage market (corporate) domination and create a land market by establishing a system of ‘conclusive titling’ of all land in the country so that ownership can be identified and land can then be bought or taken away.

Globally, the financialisation of farmland accelerated after the 2008 financial crisis. From 2008 to 2022, land prices nearly doubled throughout the world. Agricultural investment funds rose ten-fold between 2005 and 2018 and now regularly include farmland as a stand-alone asset class, with US investors having doubled their stakes in farmland since 2020.

Meanwhile, agricultural commodity traders are speculating on farmland through their own private equity subsidiaries, while new financial derivatives are allowing speculators to accrue land parcels and lease them back to struggling farmers, driving steep and sustained land price inflation.

As far as India is concerned, it is becoming a fully incorporated subsidiary of global capitalism. Displaced farmers and farm workers are pushed into urban sectors like construction, manufacturing and services, despite these sectors not generating enough jobs. This displacement facilitates the replacement of labour-intensive, family-run farms with large-scale, mechanised monoculture enterprises controlled by a few powerful transnational agribusiness corporations and financial institutions.

Moreover, India is being directed to rely increasingly on its foreign exchange reserves to buy food on the international market as it is forced to eradicate its buffer food stocks.

This process is driven by pressure from global agribusiness and finance capital, which seek to dismantle India’s public food procurement and distribution systems, including the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and the Public Distribution System (PDS). These state-backed mechanisms have historically ensured food security by maintaining strategic grain stocks and providing fair prices to farmers.

Eliminating these buffer stocks would mean that India would no longer physically hold and control its own food reserves. Instead, it would have to depend on volatile global markets to procure essential food supplies, using foreign currency reserves. This shift would make India vulnerable to price fluctuations, speculation by investment firms and manipulation by multinational corporations dominating global commodity markets.

The massive farmer protests in India were, in part, a resistance to these policies. Without buffer stocks, India would effectively be paying corporations such as Cargill to supply food, perhaps financed by borrowing on international markets.

Resistance and refusal

The narrative presented here reveals a deeply systemic crisis within capitalism—one that cannot be understood through isolated events, personality politics or short-term policy shifts.

From financialisation, predatory practices abroad and speculative markets to state-backed bailouts, war and digital surveillance, capitalism continually reinvents mechanisms to prolong its accumulation cycle.

This article exposes the underlying logic of an economic system marked by the increasing convergence of state and corporate power—a trajectory that points towards a shift away from ‘capitalism’, possibly towards a technocratic or even techno-feudalist system where e-commerce platforms, algorithms, programmable centralised currencies and monopolistic entities determine how we live.

Such developments raise urgent questions about the future shape of society and, crucially, how a mass movement might resist without being co-opted or subverted. Yet, recognising these dynamics is the essential first step in fostering informed debate and effective resistance.

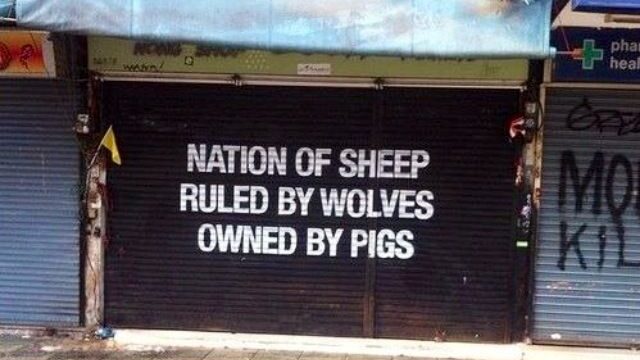

However, the hegemonic class and its media and NGOs continue to divide the population along lines of race, religion, identity politics and immigration. They do anything and everything to sow division or sedate courtesy of gadgets, games, entertainment, infotainment and sports. Their media will do all it can to keep people in the dark about what is really happening and why.

But even when people do manage to see through the smokescreen, they will try to promote apathy, convincing people that nothing can be done about any of it anyway.

They will try anything to fragment opposition and suppress movements for systemic change.

That is not to say resistance is absent—far from it, especially in the realm of food and agriculture (discussed in my books on the global food system linked to at the end of this article).

The fightback against emerging digital authoritarianism is already underway and takes many forms: rights groups are challenging mass surveillance laws and practices in the courts; campaigns are mobilising to block or roll back digital ID schemes, facial recognition and mass data retention.

Mass mobilisations against surveillance infrastructure are growing, as are acts of refusal in the form of non-compliance with digital ID requirements, opt-outs and public data obfuscation campaigns. There is also a burgeoning movement to build and promote peer-to-peer, federated or blockchain-based social networks and communication tools and to develop grassroots internet infrastructure that bypasses state and corporate control.

International solidarity is crucial, too, to expose and resist the export of surveillance technologies and the global harmonisation of repressive policies.

Meanwhile hundreds of millions endure poverty and many more face declining living standards and welfare cuts. At the same time, the super-rich have stashed an estimated $50 trillion in hidden accounts (as of 2020) and have only grown wealthier in recent years.

And here lies the crux of the matter—economic power. While resistance to the surveillance state and digital authoritarianism is vital, the deeper struggle is against the concentration of wealth and control in the hands of a global corporate and financial elite.

Across the world, workers, peasants and communities are organising through strikes, land occupations, agroecology, seed and food sovereignty movements, debt resistance and the fight to reclaim public goods. The task is to build movements capable not only of resisting but of transforming the structures of economic power that underpin the entire system.