Dumbphones, Unstacked

Recently, a friend shared an itinerary he’d received for an upcoming bachelorette party in New Orleans. We were stationed in the corner of a Basque restaurant, catching up over gildas and bomba rice, when he slid his phone across the table to show me the flyer that the bride-to-be had prepared.

The itinerary detailed NOLA’s usual suspects: Bourbon Street, booze, and beignets. However, on the second day of the schedule, wedged in between a swamp tour and a “pizza-pool party,” was an activity I had never seen explicitly listed on any group trip. The activity seemed essential for a weekend this meticulously planned to function, and yet its scheduling—so blatant, and in writing—was surprising. It felt strangely compassionate, signaling an acute understanding of what the attendees would need at that particular moment: post-swamp-tour, pre-pizza-pool-party, in an Airbnb of 17 people.

The scheduled activity was “screentime.”

This inclusion acknowledged that for guests to manage a high degree of social activity, they would require downtime. But what does it say about us that “screentime” and “downtime” have become synonymous?

Rotting or rest?

Over the past year, “rotting” has become a part of our cultural lexicon. Though “brain rot” is ostensibly pejorative, it’s often referenced with something like pride; terms like bed rot and rot girl summer have been used to describe how scrolling on a smartphone can be palliative, offering our minds a chance to relax and restore. A hibernant state, perhaps.

But rotting is rarely as rejuvenating as rest, especially if it is used to fuel avoidant tendencies. “The irony of the phone as the siren song for the restless is that it feeds and starves us both,”

Haley Nahman writes in What is rotting, if not rest?. “Scrolling shortens our attention spans, which lowers our tolerance for stillness, which inspires us to scroll more. It also makes us feel guilty, which makes us more avoidant, and more likely to seek out rotting when we need a breather.”

For me, this tracks. I’ve written before about how we use the “rot” on our smartphones—the memes, the fancams, the TikToks—to distract from the overload of information we are exposed to every day, usually on the very same device. If I am feeling overstimulated, turning to my phone only glazes over the cacophony with its own tweaky haze, rather than dulling the noise.

But it’s not just rest that smartphones have been accused of ruining; phones have become a punching bag for many of our contemporary woes. “We all know our phones are destroying our attention spans, our dopamine reward systems, our relationships,”

Catherine Shannon writes in Your phone is why you don’t feel sexy. “We know they’re numbing our feelings and experiences.”

Magdalene J. Taylor identifies the culprit simply: “It’s obviously the phones.”

The dumbphone solution

It seems that everyone is looking for a way to circumvent these issues. One of the loudest contingents is migrating to “dumbphones”—basic devices without apps, social media feeds, or the rot-inducing content designed to maximize screentime and keep us entranced in endless streams of slush.

The dumbphone solution is, perhaps surprisingly, especially popular with younger generations. In a piece called Third Places and Dumbphones,

Casey Lewis reports on Gen Z’s spiked curiosity surrounding the low-tech device:

“A growing number of Gen Zers are dumbphone-curious, with Google searches for the term spiking over the summer. Beyond the obvious benefits of embracing low-tech devices (having a working brain again), many report feeling more confident in their appearance after quitting smartphones, with reduced exposure to filtered, unrealistic beauty standards on social media. Psychologists link this trend to the Social Comparison Theory, suggesting that less screen time leads to fewer opportunities for self-criticism and more time for hobbies and self-discovery.”

One of the most visible advocates for the dumbphone movement is

August Lamm, a self-described anti-tech activist whose writing and pamphlets help readers transition away from smartphones. This is necessary, because even the most ardent dumbphone advocates admit that not having a smartphone can be tough. For

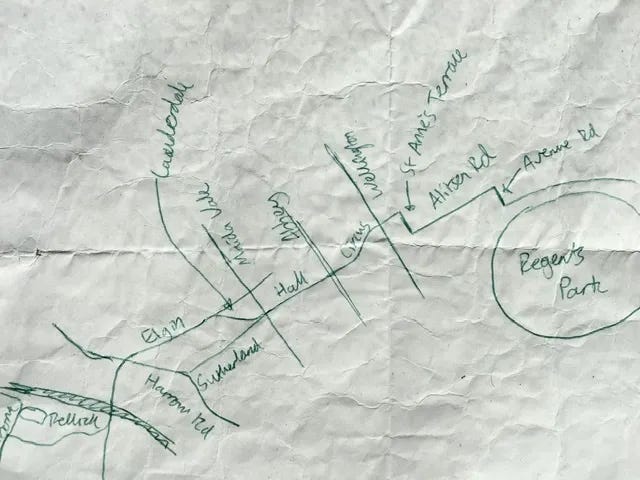

Sam Kriss, who gave up his smartphone for Lent last year, the hardest part was losing access to GPS; he found himself resorting to hand-drawn maps. Although the thought of braving the New York MTA with a hand-drawn map is somewhat terrifying, there is something appealing about reducing your environment to a sketch on the back of a napkin.

Beyond the missing functionality, being without a smartphone can also just feel awkward.

Sean Dietrich reports feeling conspicuous: “I feel pretty stupid just standing there, with nothing to look at, staring into space. Sometimes, I’m not entirely sure I’ve done the right thing, giving up my device. If I’m being honest, I feel lonely without my old phone. I feel left behind. I must appear pretty boring compared to other people I see in public, importantly tapping away on their phones.”

And, as

Alexander Raubo writes in Your dumbphone won’t save you, it’s not as if the cellphones from 30 years ago weren’t distracting: “We don’t even have to read philosophy from the flip-phone era to get a sense that many of the criticisms directed towards smartphones today were directed towards dumbphones twenty years ago. Watching Sex and the City reruns, it’s striking how disruptive and intrusive Nokias and flip phones were.”

The dumbphone movement can sometimes seem more like a trend—an aesthetic, even—than a sustainable, practical response. Last fall, during the final glass pours of a dinner party, someone proudly presented a dumbphone and asked for my number. I awkwardly typed my name into their contacts, surprising myself with the muscle memory recall of T9 texting. It was charming at the moment, but looking back, it felt like a gimmick. Reader, we never texted.

Let your phone die in your hands

It seems to me that the solution must be somewhere in between abstinence and submission. As

Sean Dietrich puts it, “I want to use a smartphone, not be used by my smartphone.”

Instead of trying to turn back the clock on phones and the internet, recognizing our power to set limits on their influence is a more realistic path forward. I like

toni bravo’s concept of “letting your phone die in your hands.” Rather than being consumed with where you’ll get your next charge, this method allows you to recognize that your phone—like leftovers, milk, or fruit—has a best-before date. And it’s okay to let its powers wane. Bravo writes:

“I’ve decided to allow my phone to die in my hands at the end of the day. To witness my battery slowly drain from green to yellow and then red and not reach for a charger. It felt wrong at first, but it’s become one of my favorite things to do. Yeah, ‘do not disturb’ exists, but nothing beats do not resuscitate.”

Bravo’s reframe doesn’t require us to “dumb” our technology down. Instead, it acknowledges that screentime—whether productive or just mindless scrolling—serves a purpose for many of us. There’s a natural lifespan for everything, and, by not making our phones immortal, we remember that we are the ones who should be living.