Empire Windrush — the Stolen Ship Which Sank Great Britain

The Second World War was an anti-racist crusade by a deeply racist Britain, and by its end the country was so broken and short of men that the country was rebuilt by West Indian ex-servicemen. That, with only slight exaggeration, is now the core of the official history of the United Kingdom.

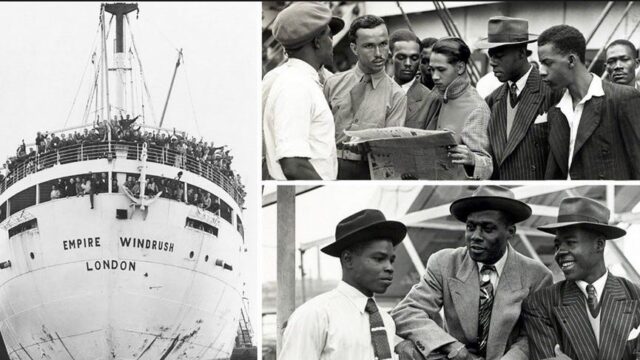

Within this all-pervasive and radically dishonest narrative, the chief propaganda icons are photographs and grainy film clips of an elderly passenger liner, the Empire Windrush. [1]

The ship was named for a tributary of the River Thames, the Windrush, a rare and beautiful trout stream, which winds its way through some of the most quintessentially English countryside and villages in the land. It is a bitterly ironic that the ship named after it has become synonymous with the mass immigration which is turning the indigenous English into strangers in their own built-over homeland.

In as far as the West Indians who formed the advance guard of the Third World flooding of Britain were all the descendants of enslaved Africans, the ship may be seen as symbolic of the Revenge of the Slaves. Yet closer examination of the history of the ill-fated liner reveals deeper irony still, or perhaps a stunning example of poetic justice. For the Empire Windrush didn’t start her life with that name, she was a war prize – booty from Great Britain’s war against Nazi Germany and the ‘racism’ it is now seen to epitomize.

The outline of this part of the story was related in The Barnes Review in a 2018 article by Sydney Secular, ‘The SS Empire Windrush: The Mayflower in Reverse’. [2] But even though that was well under a decade ago, the lies told about the Empire Windrush have since reached such epic proportions that the ship’s history and myths need to be re-examined.

The truth needs to be put on record for the sake of two distinct groups who should be interested in it: Future generations of native Brits who may try to wade through the Diversity and Enrichment propaganda to find out how their ancestors lost their country, and Americans who may still underestimate the ruthless dishonesty of those who intend – ICE deportations of illegals notwithstanding – to turn them into a similarly oppressed minority in their own land.

Let us begin by examining the history of the ship herself. Launched in 1930 by Blohm & Voss in Hamburg for the Hamburg Süd shipping line, she began as a passenger liner and cruise ship. [3]

Her maiden voyage was to Buenos Aires, carrying German emigrants to Argentina, but the Great Depression soon caused a global slump in shipping, including Hamburg Süd’s passenger business. The Monte Rosa was switched to making cruises to the UK and Norway, on one of which she ran aground just off the Faroe Islands. As trade picked up again, Monte Rosa was back on her route between Hamburg and Buenos Aires, making more than twenty round trips on the route.

On 23 July 1934 Monte Rosa ran aground off Thorshavn in the Faroe Islands but was refloated on the next high tide. In 1936 she rendezvoused at sea with the airship LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, and a bottle of Champagne was hoisted from her deck to the airship.[4]

After Hitler assumed power in 1933, the ship was used to spread Nazi ideology among the German-speaking community in South America. When in port in Argentina, she hosted Nazi rallies for German Argentines. The new German ambassador, Baron Edmond von Thermann, sailed to Argentina aboard Monte Rosa. He disembarked wearing an SS uniform to address an enthusiastic crowd. The ship was also a venue for Nazi gatherings when docked in London. [5]

In 1937 the Nazi government chartered Monte Rosa, and two of her Hamburg Süd sister ships to provide cruise holidays for the state-owned Kraft durch Freude (”Strength through Joy”) programme. This aimed to give working-class German families the chance to enjoy luxury holidays of the sort previously reserved for the well-to-do, while the lectures which went alongside the sports activities and concerts were intended to cement their loyalty to the regime. [6]

The KdF cruises ranged from eight to 20 days in duration. One route went north from Hamburg, along the Norwegian coast and travelling as far as Svalbard. Another was through the Mediterranean, stopping in Italy and Libya, and travelling as far east as Port Said.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, the Monte Rosa was requisitioned by the Kriegsmarine and converted into a troopship and support vessel.

In April 1940, she participated in the German invasion of Norway, whose waters her crew already knew well. Later, she was assigned as an accommodation and recreational vessel for the battleship Tirpitz in northern Norway, stationed in Altafjord. [7]

In October 1943, after Royal Navy midget submarines damaged Tirpitz in Operation Source, Monte Rosa transported hundreds of civilian workers and engineers to Altafjord to repair the battleship in situ, as Germany feared moving it to a dockyard.

On March 30, 1944, British and Canadian Bristol Beaufighters from RAF 144 and RCAF 404 Squadrons struck her with torpedoes, rockets, and cannon fire. Despite claims of two torpedo hits and significant damage, she limped to Aarhus by April 3.

In June 1944, Norwegian resistance fighters attached limpet mines to her hull in Oslo harbour, aiming to disrupt her use for troop movements. The mines detonated near Øresund, damaging her further. Another explosion in September 1944—possibly a mine—killed 200 aboard.

In January 1945, she was briefly converted into a hospital ship but was damaged by a mine. After temporary repairs, she evacuated 5,000 German refugees from the advancing Red Army, reaching Copenhagen under tow but safely, unlike other liners which were sunk by Soviet submarines.

The worst of these deadly tragedies was the sinking of another KdF liner, MV Wilhelm Gustloff on January 30, 1945. Packed with refugees fleeing the brutal vengeance of the Red Army, the torpedo and the icy water cost 9,000 to 9,400 lives, most of them civilians. This far exceeding the death toll of more famous sinkings like the Titanic (1,517) or Lusitania (1,198)—making it the single deadliest ship sinking in history. [8]

The Royal Navy seized Monte Rosa as a prize of war in May 1945 at the naval base at Kiel, Germany, following the German surrender. The ship was repaired in Denmark that summer and refitted in the north-east English town of South Shields. In 1946, she was renamed HMT Empire Windrush on January 21, 1947, entering British service.

The British Merchant Navy had hundreds of “Empire Ships”, sixty of them, including the former Monte Rosa, being named after UK rivers. All are now more or less forgotten, except for the Empire Windrush, which was assigned a role which made her a key part of Britain’s fatal post-WW2 history.

Even as they imposed even stricter rationing than during the war, and with the housing crisis created by Hitler’s bombs and rockets still unresolved, the post-war Labour government opened the doors to coloured immigration.

The trickle which became a flood started in 1947, but the immigration programme only really hit the news on 22nd June, 1948, when the Empire Windrush landed at Tilbury, on the Thames downstream from London, with her first cargo of West Indian immigrants.

The passenger list for the first run was officially 492 people but, for an unknown reason which we can only guess at, a huge number of stowaways had been allowed to nearly double that number. The ship’s manifest, now in the United Kingdom National Archives, shows that 802 passengers gave their last place of residence as a country in the Caribbean. [9]

Passengers who had not already arranged accommodation were temporarily housed in the now disused Clapham South deep air raid shelter in southwest London. This was less than a mile away from the Employment Exchange in Brixton, where some of the arrivals sought work, and which quickly became notorious as a West Indian ghetto.

The stowaways were given brief prison sentences, but were allowed to remain in the UK after their release [10], setting the precedent for decades of rewarding illegal migrants for their law-breaking, something which continues to outrage millions of native Brits to this day.

Newspapers like The Times and Guardian covered the arrival with a mix of curiosity and mild alarm. Far from greeting the new arrivals as saviours of a shattered country, as liberal propaganda now suggests, their headlines focused on housing shortages and the limited job prospects for the men and women they called “the Jamaican unemployed”.

Through the summer of 1948, a few more boatloads had arrived, but the total number of arrivals was still only a few thousand. That, however, was about to change, as the political elite prepared to open the floodgates.

The British Nationality Act 1948 was a landmark piece of legislation introduced by Clement Attlee’s post‑war Labour government. It replaced the old system of British subjecthood by creating a single, unified nationality – “Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies”. This change was explained as needed to reflect the changing nature of the British Empire, uniting people from Britain and all its colonies under one legal status.

It granted British citizenship to nearly all those born or naturalised within the entire British Empire. By extending citizenship rights to people in the colonies the Act at a single stroke destroyed Britishness based on geography, let alone on ancestry.

The Labour Party’s internationalism and scarcely-concealed loathing for Britain and her indigenous peoples explain the role of the left in this appalling betrayal, but this should not blind us to the culpability of the right.

The Tories believed that they needed to find a way to create the impression that the Commonwealth nations and their newly independent citizens still had a special place in post-imperial Britain. The party’s liberals and imperialists alike were both attracted to the idea of giving Commonwealth citizens automatic British citizenship.

When wiser heads pointed out that this meant giving the right to move to Britain to a quarter of the world’s entire population, the plan’s supporters simply lied, reassuring a concerned public that the legal change was a symbolic gesture and that mass immigration was not on the cards.

The public’s anxiety was based to a large degree on the fact that Britain’s colonial experience, and two World Wars in very recent memory, meant that millions of people had direct personal experience of Asia and Africa. This gave them a very good idea of what mass immigration would bring in its wake. What is now decried as racism and prejudice was in fact well-informed awareness of reality.

Winston Churchill was still the Tory leader and those who have swallowed the myth of his “racism” and common-sense patriotism might expect him to have opposed the Labour plan. In the event, however, his nostalgia for the Empire led to him effectively nodding through the legislation, which had broad cross-party support.

The Hansard parliamentary records show that the British Nationality Act 1948 sailed through the House of Commons. The Second Reading of the bill, on May 11, 1948, proceeded without a division – meaning it passed without a formal recorded vote, as opposition was minimal. The Third Reading, the final stage in the Commons, also saw no significant resistance necessitating a division, and the bill moved smoothly to the House of Lords, where it was similarly approved.

Hansard records also show that Churchill made speeches on various topics that year, but that he said nothing against the British Nationality Bill, even though he was supposedly opposed to significant Commonwealth immigration.

While the Conservative hierarchy believed that immigration was needed to strengthen ties between Britain and the Commonwealth, there is no doubt that they were also influenced by the desire of many big businesses for cheap labour. With unemployment at historic lows of about 2%, the bargaining power of British workers was uncomfortably strong for the bosses.

Tough talk about immigration might be rolled out by individual Tory candidates at election time in areas where it was an issue, but there was never any will to turn it into effective action. Thus, we see that the entire political elite shares the guilt for having set in motion the changes now scheduled to make the indigenous British a minority in their own country by around 2060.

Over the few years after the passing of the British Nationality Act, the Windrush made perhaps eight more voyages carrying immigrants to Britain. The usual number was between 800 to 1,000 people.

Her time as an immigration ferry came to an end at the start of 1954. The Empire Windrush was sent to Yokohama, from whence she began the long journey home, picking up British servicemen and their families from various outposts of the dying Empire.

She called at Kure, Hong Kong, Singapore, Colombo, Aden, and Port Said. Her passengers included recovering wounded United Nations servicemen from the Korean War, including members of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment who had been wounded at the Third Battle of the Hook in May 1953.

The voyage was beset by engine breakdowns and other problems, including a fire after leaving Hong Kong. She took ten weeks to reach Port Said, where a party of 50 Royal Marines from 3 Commando Brigade brought her up to nearly full passenger capacity, with 1,498 people aboard. [10]

At 0617 hrs on 28 March, Windrush was in the western Mediterranean, off the coast of Algeria, when an explosion in the engine room killed four crewmen and started a fierce fire.

The order to abandon ship was given less than half an hour later. The fire made it impossible to launch all her lifeboats; some of her passengers and crew spent up to two hours in the water, but all were rescued.

Twenty-six hours after the ill-fated vessel was abandoned, HMS Saintes of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet reached her. The fire was still burning fiercely but a party from Saintes managed to board her and secure a tow cable.

The attempt to tow the stricken vessel to Gibraltar ended early on 30 March 1954, with the Empire Windrush sinking, taking the bodies of her four dead crewmen 8.500 feet to the bottom of the Mediterranean.

Although the Windrush became symbolic of post‑war West Indian immigration, it was not alone, so sadly her sinking made no difference to the rate of Britain’s transformation. Many other vessels also carried migrants from the Caribbean and other parts of the Commonwealth, contributing collectively to what is now known as the “Windrush Generation.” [11]

A great deal of propaganda nonsense surrounds this development. The mainstream media and school curriculum treat it as some sort of foundational event, a crucial moment in British history when an utterly exhausted nation was saved from despondency and collapse by the “immigrants who came to rebuild Britain”. The truth, as is so often the case, is very different.

First, the new arrivals did not arrive to “rebuild Britain”, but to escape unemployment and economic dislocation at home. U.S. pressure for global free trade had led to a systematic reduction in the old Imperial Preference system which had favoured produce from empire countries, including sugar and bananas from the West Indies.

During the 1947 GATT negotiations, the U.S. demanded reductions in preferential tariffs, threatening to withhold Marshall Aid if Britain did not comply. The Labour government surrendered, plunging the West Indies into a recession which went on for decades as Imperial Preference was phased out. [12]

Most of the West Indians who moved to Britain did so because they were either unemployed or saw no prospect of building better lives at home.

Nor, in general, did the West Indians “rebuild” anything. Ask any Brit old enough to remember even the 1970s, let alone the 1950s, whether they used to see black men working on building sites, or helping construct motorways. They will say ‘no’, because those jobs were done overwhelmingly by British labourers or Irishmen.

Did post-war Britain see immigrants working down the pits or in steel mills or shipyards? Yes, there were some, but they were overwhelmingly refugees from Communist Eastern Europe. Roughly 200,000 Eastern European refugees entered Britain in the decade following World War II. The vast majority were Poles – granted settlement under the Polish Resettlement Act of 1947 – as they fled Communism. [13]

The truth is that the West Indians took low-skilled jobs, such as bus conductors or nursing auxiliaries and hospital cleaners. Useful jobs for low wages, but they didn’t “rebuild Britain”.

Another propaganda line is that the newcomers had fought for Britain in large numbers. [14] Around 7,000 West Indians did serve in the RAF. Over 400 of them earned commissions or gallantry medals and about 400 died in air operations. The 139 (Jamaica) Squadron, funded by Jamaican donations, became the poster child of the Caribbean contribution.

It was indeed a touching contribution, but it did not turn the tide of the war. The figures must be put into context: Just under one million British men and women served in the Royal Air Force during the war. The total RAF death toll was 70,253, with Bomber Command’s 55,573 dwarfing Fighter Command’s 4,500. Coastal Command (5,866 dead), training units, and others fill the gap.

The West Indians who died in the RAF – whose sacrifice is one of the “justifications” now given for turning indigenous Britons into a minority in their own homeland – therefore made up less than 0.6% of the total casualties.

The RAF’s 7,000 West Indians must also be weighed against the numbers who came from the White Dominions: 50,000–55,000 Canadians, of whom 9,919 died; 27,000–30,000 Australians, of whom 6,458 never made it home, and 8 ,000–10,000 South Africans. Including casualties in the SA Air Force, a total of 4,727 South Africans died fighting for Britain in the air.

Between 11,000 and 12,000 New Zealanders served in the Royal Air Force. Some 3,900-4,000 were killed and about 1,600 more lost their lives in the RNZAF. The population of New Zealand in 1939 was just 1.6 million population, only just over half that of the British West Indies.

There were also 2,409 Rhodesians who volunteered to join the RAF, all of them from the white population, which totalled 66,000 at most. Of those, 698 were killed on active service, a contribution proportionally much greater than the 400 or so losses suffered by the West Indians, who were drawn from a total population of more than three million.

What of the other services? According to the Imperial War Museum and National Army Museum, around 20,000 West Indians served across the Army, Royal Navy, and Merchant Marine. Up to 17,000 of these served in the Army, many of them as labourers or safely in the Caribbean itself, guarding against U-boat landings which never came.

Excluding Canadians and the massive contribution of 2.5 million Indians (disproportionately Sikhs), a total of 3.3 million men served in the British Army during World War Two. The West Indian contribution was thus just over a half of one per cent. It wouldn’t have caused Hitler any sleepless nights!

As for the idea that Britain had lost so many people that it was necessary to ship in replacements from her former colonies, the same years which saw the beginning of the Third World flood into the UK also saw the political elite working hard to encourage the natives to leave the country.

Between 1959 and 1972, more than one million Brits emigrated to Australia under the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme, becoming known Down Under as ‘Ten Pound Poms’, All of them under 48 years old and having passed a rigorous health check. [15]

An additional 76,676 left for New Zealand under a similar scheme. On top of this, many thousands of orphans and illegitimate children in care homes were also shipped off to Australia. Replacement immigration was a matter of policy, not necessity.

The greatest irony in all this is that the British got exactly what they fought for. The forced war against Nazi Germany demonised as unspeakable “racism” the very idea that white people had a right to advocate for their own interests, or even to an identity at all. The conflict completed the bankruptcy of Great Britain and opened the way for the dismantling of the Empire. In the capital of that empire today, white Britons are now a rapidly shrinking minority.

Most of the children they do have now speak not with the “Cockney” style accent of their parents and ancestors, but instead use a crude patois known as Multicultural London English (MLE). This has its origins in the West Indian accent which first arrived with the so-called Windrush Generation. [16]

The role of the Empire Windrush in this gruesome transformation has a strong hint of karma about it. The fact that the iconic vessel in which many of the first wave arrived was stolen from defeated Germany is a stunning irony of History. Britain’s post-war transformation into a multicultural hell-hole may be seen as an unintended consequence of her defeat of Nazi “racism”.

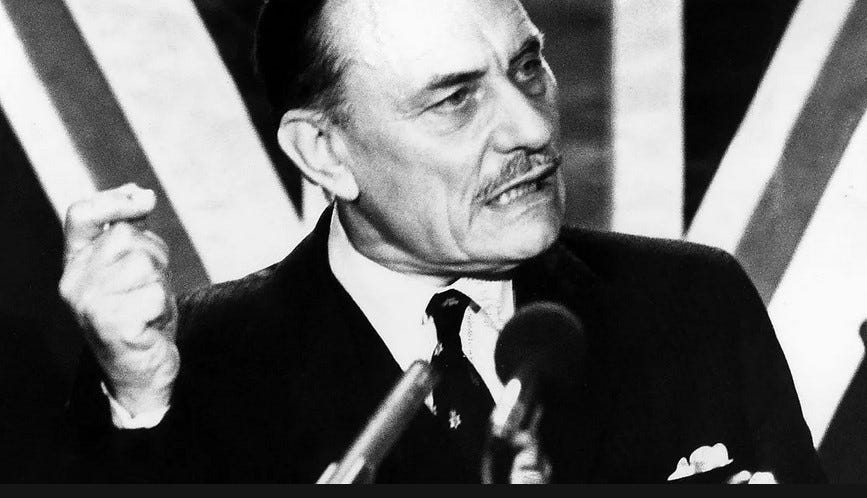

After the brilliant Tory maverick MP Enoch Powell spoke out against the terrible danger from immigration in 1968, the Labour MP Tony Benn sneered that: “The flag of racialism which has been hoisted in Wolverhampton is beginning to look like the one that fluttered 25 years ago over Dachau and Belsen.” [17]

In the years since 1948, efforts by British patriots to warn against and try to reverse the immigrant tide have been met with ruthless propaganda campaigns, not just about the supposedly central role of the “Windrush Generation” in “saving and rebuilding Britain”, but also about the deadly toll of Nazi “racism”.

The propaganda horror stories about the Germans under Hitler have been used as a crushing moral club to beat down British resistance to dispossession and replacement. The stories of Nazi “death camps” came back to haunt the British people, as did the stolen Kraft durch Freude vessel Monte Rosa, aka the Windrush.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnott, Paul (2019). Windrush: A Ship Through Time. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-9120-9.

Barnes, James J; Barnes, Patience P (2005). Nazis in Pre-war London, 1930-1939: The Fate and Role of German Party Members and British Sympathizers. Sussex Academic Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84519-053-8.

Hansen, Clas Broder (1991). Passenger liners from Germany, 1816-1990. West Chester, Pa: Schiffer Pub. ISBN 978-0-88740-325-5. OCLC 1023218448.

Haws, Duncan (1985). New Zealand Shipping Co. & Federal S.N. Co. Merchant Fleets. Vol. 7. Burwash: Travel Creatours Ltd Publications. ISBN 0-946378-02-9.

Mitchell, Otis C, ed. (1981). “Karl H Heller – Strength through joy: regimented leisure in Nazi Germany”. Nazism and the common man: essays in German history (1929-1939) (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-1546-1.

Phillips, Mike; Phillips, Trevor (1988). Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-653039-8.

Mitchell, WH; Sawyer, LA (1995). The Empire Ships. London: Lloyd’s of London Press Ltd. ISBN 1-85044-275-4. OCLC 246537905.

Seybold, WN (1998). Women and children first – the loss of the troopship “Empire Windrush”. Ballaugh, IoM: Captain WN Seybold. ISBN 0953354105. OCLC 39962436.

ENDNOTES

1. Phillips, Mike; Phillips, Trevor (1988). Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-653039-8.

2. The SS Empire Windrush: The Mayflower in Reverse. The Barnes Review vol XXIV, Number 1

3. Schwerdtner, Nils (2013). German Luxury Ocean Liners: From Kaiser Willhelm to Aidastella. Amberley: Amberley Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4456-1471-7. OCLC 832608271.

4. “D-LZ 127 “Graf Zeppelin”“ (in German). Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek. Retrieved 26 December 2019

5. Barnes v& Barnes, p.22

6. Mitchell, Otis C, ed. (1981). “Karl H Heller – Strength through joy: regimented leisure in Nazi Germany”.

7. Haws p.69

8. Begley, Sarah (29 January 2016). “The Forgotten Maritime Tragedy That Was 6 Times Deadlier Than the Titanic”. Time. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

9. Rodgers, Lucy; Ahmed, Maryam (27 April 2018). “Windrush: Who exactly was on board?”. BBC News. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

10. “Students From The Colonies”. The Times. London. 9 May 1949. p. 2.

11. “Who were the Windrush generation and what is Windrush Day?”. BBC News. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

12. The Attlee Government, the Imperial Preference System and the Creation of the GATT. Richard Toye. The English Historical Review. Vol. 118, No. 478 (Sep., 2003), pp. 912-939

13. Kay, Diana; Miles, Robert (1998). “Refugees or migrant workers? The case of the European Volunteer Workers in Britain (1946–1951)”. Journal of Refugee Studies. 1 (3–4): 214–236. doi:10.1093/jrs/1.3-4.214.

14. WW2: How did the heroes of the Caribbean help win the war? https://www.bbc.co.uk/teach/articles/zn96d6f

15. Post World War II British Migration to Australia”. Museums Victoria Collections. 2014.

16. “How Is Immigration Changing Language In the UK?”. Vice.com. 24 February 2016. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

17. David Butler; Michael Pinto-Duschinsky (1971). British General Election of 1970. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-1-349-01095-0.

https://nickgriffin544956.substack.com/p/empire-windrush-stolen-ship-which