First AI-Designed Drug Nears Approval – is It Reliable?

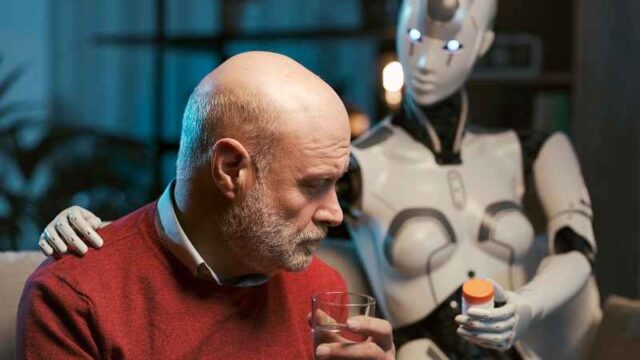

For decades, drug development has been one of the slowest, most expensive, and most failure-prone processes in modern science. Artificial intelligence, however, could break this bottleneck. An experimental drug designed largely by AI has now entered final phase trials in record time and is on track to become the first AI-designed drug approved for human use. Some are calling it a medical breakthrough, while others see it as a disturbing shortcut that replaces sound medical insight with machine-based optimization.

AI designs a new medicine

The drug nearing approval was developed by Insilico Medicine, an AI-focused biotech company that uses machine learning models to identify disease targets and generate potential compounds for their treatment. The target of the new drug is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)—a fatal lung disease that kills approximately 40,000 Americans annually and for which there is no known cure. Incredibly, development has now progressed from target discovery to human trials in less than two years, writes G. Calder .

To put that in context, conventional drug discovery typically takes about 5 years to progress to human trials, followed by another 6-8 years of clinical trials and regulatory review. From start to finish, most drugs take 10 to 15 years, with an estimated 90% failure rate once human trials begin.

AI can dramatically shorten the early discovery phase—the slowest and most expensive part. Insilico’s process replaces years of laboratory iterations with algorithmic screening of millions of molecular structures, predicting toxicity, simulating protein folding, and proposing candidate compounds in a matter of weeks instead of years.

How the process is accelerated

Traditional drug development relies on slow, iterative laboratory work: hypothesis, experiment, failure, revision. AI systems circumvent this by training on vast datasets of chemical structures, biological pathways, and historical test results. This allows researchers to reject unlikely candidates outright and focus their resources on compounds with the highest predicted success rates.

Simply put, AI doesn’t understand biology, but it recognizes patterns on a large scale. It can digitally test millions of theoretical molecules before a human chemist synthesizes a single one.

This efficiency means pharmaceutical companies can reduce their development costs by 30-70%, which is why so much venture capital is now being invested in the sector. It’s estimated that over $60 billion has been invested globally in AI biotech startups over the past five years, with major pharmaceutical companies partnering or investing independently to keep pace.

An optimistic vision

There are genuine humanitarian arguments for AI-accelerated medicines. Rare diseases, neglected conditions, or diseases with small patient populations have always been commercially unattractive. By making development faster and cheaper using AI, previously unattainable treatments could finally become realistic. There is also the potential for personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to genetic profiles in ways that human research cannot or will not explore.

An important clarification here is that AI-designed drugs are still being tested on humans. Regulatory agencies have not permitted deviations from safety standards, and clinical trials remain mandatory. Therefore, a positive outlook emphasizes that AI does not replace scientific judgment , but rather complements it with rapid trial and error. Faster discoveries do not automatically mean lower standards.

So, what’s the problem?

The concern lies not so much in the speed itself, but rather in what that speed displaces. AI systems often operate as black boxes, delivering effective results but failing to provide a clear explanation of the causal reasoning. In many sectors, this opacity isn’t a major problem. In medicine, it is.

Knowing exactly how and why a drug works is crucial for predicting side effects, long-term risks, and interactions with other treatments. If development timelines are drastically shortened, there’s less room for exploratory research—the slow, often ambiguous human work that yields conceptual insight rather than statistical certainty. What happens when regulators approve drugs that have performed well in trials, but whose mechanisms are still only partially understood?

AI has a worrying track record outside the pharmaceutical industry

In recent years, AI systems have repeatedly demonstrated their tendency to generate reliable but inaccurate results—a concept we explore in more detail in this article . Large language models fabricate technical details and quotations; image recognition tools misclassify objects in safety-critical environments; automated decision-making software continues to reinforce biases in politics and beyond.

These failures do not imply malicious intent, but they do point to structural limitations.

AI models are optimized for probability rather than truth. They perform best in environments where patterns are stable and recognizable, and the consequences are reversible. Biology is neither of these things. Errors in drug development—misjudgments of toxicity, side effects, or long-term interactions—are costly, irreversible, and sometimes fatal.

Trading speed for safety has backfired before

Medical history offers clear warnings. Some of the most notorious drug disasters of the 20th century occurred within entirely human-run systems that followed their own scientific standards. Thalidomide, one of the most famous examples, was approved in several countries in the late 1950s and passed all required tests before causing catastrophic birth defects. The safeguards that now slow drug development were put in place in response to such failures.

The concern isn’t that AI will produce more bad drugs, but that it could produce bad drugs faster and on a larger scale, before institutional safeguards can adapt.

The precedent

If Insilico’s AI-designed IPF treatment is approved, it would set a powerful precedent. Suddenly, the idea that drugs can be produced faster than scientists can fully understand them would become normalized, and over time, this could also transform diagnostics, treatment protocols, and the design of clinical trials.

The challenge for regulators and society now is to decide how much opacity they can trade for speed. Trust in medicine must be based on more than just results—trust in the process is also crucial.

Final Thought

Patients long underserved by traditional research models—because their illnesses are not economically viable to cure—may find hope if AI-designed drugs are successful. But the promise of speed shouldn’t obscure the risks of substituting optimization for understanding. The consequences of mistakes are profound in medicine, and slow development has, in a sense, offered a hedge against such risks. As AI accelerates discovery, how can we ensure that progress doesn’t overwhelm the safeguards that protect us all?

https://www.frontnieuws.com/eerste-door-ai-ontworpen-medicijn-bijna-goedgekeurd-is-het-betrouwbaar