Hiroshima at 80: Setting the Abhorrent Precedent

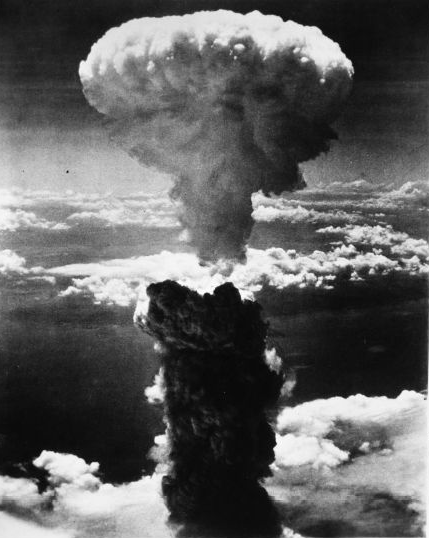

August 6th marks the 80th anniversary of mankind’s most cataclysmic and ignominious achievement: The first weaponized use of an atomic bomb. At approximately 8:15 in the morning, the bomb “Little Boy” detonated over the city of Hiroshima, Japan. While estimates have varied between 70,000 and 140,000 dead, the sheer magnitude of devastation caused to a largely civilian population cannot be understated. To this day, much debate rages on regarding the necessity of such weapons in the closing chapter of the Second World War.

The current orthodoxy of American military history, however, stands firmly entrenched that the usage of this bomb (and a subsequent one in Nagasaki three days later) was critical to ending the war quickly and saving the lives of countless Americans and even Japanese civilians who would have assuredly died in the ensuing operation to seize the entirety of mainland Japan. But how vital was the atomic bombing truly to ending the war? A deeper dive into contemporary sources reveals that the bombing was needless, cruel, and firmly established an abhorrent precedent for a newly established global hegemon.

Operation Downfall

Modern military historians desperately cling to the notion set forth by former War Secretary Henry Stimson, as articulated in the February 1947 issue of Harper’s Magazine, that, if forced to carry a ground invasion of Japan to conclusion, it would “cost over a million casualties, to American forces alone.” This invasion, dubbed “Operation Downfall,” was estimated by Stimson’s calculations to last well into 1946 and would have entailed that “additional losses might be expected among our allies” and that “enemy casualties would be much larger than our own.”

And while a large preponderance of scholarship on the matter seeks to reaffirm these claims, it was a dubious metric even at the time. As Barton J. Bernstein wrote in a 1999 issue of the Journal of Strategic Studies, no pre-Hiroshima literature can be found that would back up these claims. It appears to be a postwar invention by Stimson, Truman, et al., to justify the decision. This is an important distinction, as the bulk of pro-atomic weapon usage advocates rely heavily on this claim. However, perhaps surprisingly to some, the decision was questioned by many senior military leaders within the United States military even at the time.

Contemporary Dissent

The list of senior contemporary military figures that, whether quietly or in confidence to the president, questioned the necessity is extensive and awe-inspiring. These men were either responsible for waging the conduct of the war or were in position to advise the president directly. What follows are some key excerpts that help to challenge the need for the August 1945 case usage of such an abominable weapon.

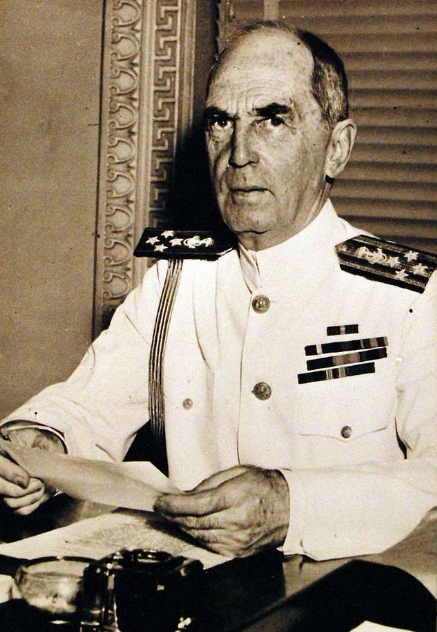

Admiral William D. Leahy (Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief, 1942-1949)

“It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.

It was my reaction that the scientists and others wanted to make this test because of the vast sums that had been spent on the project.

‘Bomb’ is the wrong word to use for this new weapon. It is not a bomb. It is not an explosive. It is a poisonous thing that kills people by its deadly radioactive reaction more than by the explosive force it develops.

The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that, in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarian of the Dark Ages.“

Admiral Leahy wrote the above in his 1950 memoir, “I was there: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman.”

While Ike did not serve in the Pacific Theater, he was a five-star general (and later 34th President of the United States) and as such his opinion carries heavy weight in the historical record. In his 1963 memoir Mandate for Change, he recounted his discontent with the bomb:

“During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to [Secretary of War Stimson] my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum of loss of ‘face.’ The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude, almost angrily refuting the reasons I gave for my quick conclusions.”

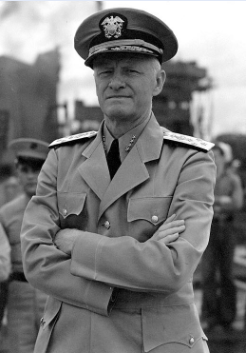

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet)

The commander of the very theater in which the bomb was dropped reportedly also felt that the weapons were not necessary to end the war. In a 1946 statement, he told a group of scientists that the military was not responsible: “I am informed that the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japanese cities was made at a higher level than that of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, according to the National World War II Museum. This statement was made in response to Admiral Halsey’s (Third Fleet Commander during WWII) claim that “The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment. It was a mistake to ever drop it.”

General Douglas MacArthur (Commander, Allied Forces, Southwest Pacific)

Perhaps most surprisingly (given later proclivity to advocate for atomic warfare in the Korean War) was General MacArthur, who, confiding to his personal pilot, was “appalled and depressed by this Frankenstein monster.” He is also listed as a dissident towards the usage of the bomb in later years.

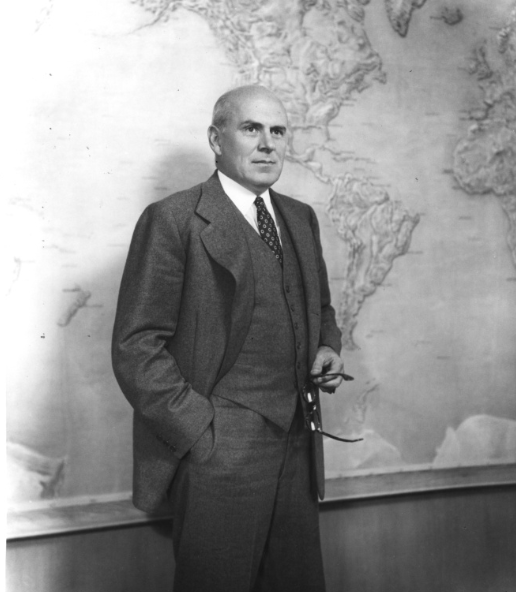

John J. McCloy (Assistant Secretary of War)

Stimson’s own assistant, John J. McCloy, was another key advisor who claimed opposition to the usage of the bombs on cities. McCloy, a veteran himself, understood the personal cost of war, and during a June 1945 meeting with the president (and other senior advisors), McCloy stated, “We ought to have our heads examined if we do not seek a political end to the war before an invasion…We have two instruments to use: first, we could assure the Japanese that they could retain their emperor. Second, he said, we could warn them of the existence of the atomic bomb.”

His imploring of a political solution, especially one that could save face for the Japanese, is vital to understanding the nature of ending the war with Japan. As it turns out, the very condition that was offered pre-Hiroshima was ultimately accepted regardless after Nagasaki.

While such quotations now form the backbone of what many may suggest is a “revisionist” view of history, these were the men who had the most stake in the execution of World War II. Men who know what total war looked and felt like. Their thoughts on the matter do not serve as mere revisionist talking points – they completely upend the orthodox framing of 1945 atomic warfare.

Challenging the “To the Last Man” Narrative

One of the biggest aspects of this discussion hinges on the notion that Japan must totally capitulate to win the war. Advocates of the bomb argue, based on Stimson’s perspective, that Japan was willing to fight to the very last man. However, as we have established, very senior leaders of the day did not uniformly believe this. This further comes into question when one recognizes that the ultimate terms of surrender, namely that the emperor of Japan remain in place, was a viable option before the bombing of Hiroshima.

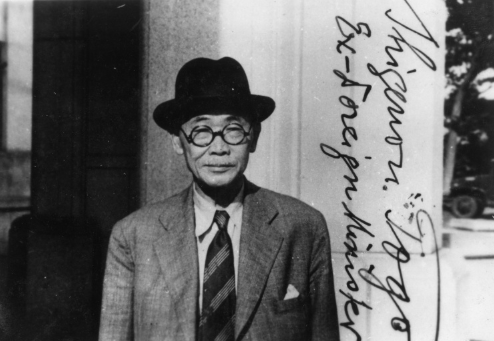

Japanese sources from the time, while fractured and chaotic due to extreme disagreements between various senior leaders, largely indicate that it was understood that the war was lost and that Japan needed to sue for peace. With no viable navy or air force left at its disposal, and an army that had been decimated by a war on multiple fronts, Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo began planning for surrender. In a cable that was intercepted on July 12th, 1945, Togo wrote to the Japanese ambassador to the Soviet Union to “sound out the possibilities of utilizing the Soviet Union in connection with the termination of the war.” While the Japanese view on their occupation of East Asia was an “aspect of maintaining world peace,” Togo also notes that “England and America are planning to take the right of maintaining peace in East Asia away from Japan, and the actual situation is now such that the mainland of Japan itself is in peril.”

“Japan is no longer in a position to be responsible for the maintenance of peace in all of East Asia, no matter how you look at it.”

The war was over, and Japan knew it – a month before Hiroshima. Togo felt that the most prudent measure to end the war while still, at the very least, maintaining a homeland, was to ask for Soviet intercession in peace talks with the allied forces. He recognized that very little stood between Japan and “unconditional surrender,” and that any steps that could be taken immediately must be done. He warned against “loose thinking which gets away from reality.” Sadly, the American government would itself give way to the same such loose thinking that had already led to so much wanton death and destruction during the war.

Conclusion

It is difficult to put into words the weight that atomic warfare brought to the conclusion of the Second World War. It served as a horrifying and needless bookend to the worst catastrophe in the history of mankind. Senior leaders of the day recognized that in the dying embers of WWII, such weaponry was reckless and not needed to secure victory. Japan no longer had a functional navy or air force. Its army was depleted and demoralized after over a decade of war. Many of its senior political leaders were ready to end the war, and only sought minimal face-saving measures to do so. When viewed through the lens of nearly a century of clarity, it is hard to come away from any conclusion other than that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were cruel signaling tools, with hundreds of thousands of innocent souls placed squarely in their experimental crosshairs.

Now, 80 years later, it is still necessary to reflect on the decision to use these weapons against largely civilian populations. Indeed, it is imperative now, as much as ever, to question the orthodoxy that has taken hold of so much of accepted military history. The inventories of nuclear weapons have grown to unbelievable heights in the subsequent decades, both in quantity and yield. Failure to recognize historical off-ramps to such calamity will only serve to encourage their usage once again in the future.

https://brownstone.org/articles/hiroshima-at-80-setting-the-abhorrent-precedent