How Gen X Kids Entertained Themselves

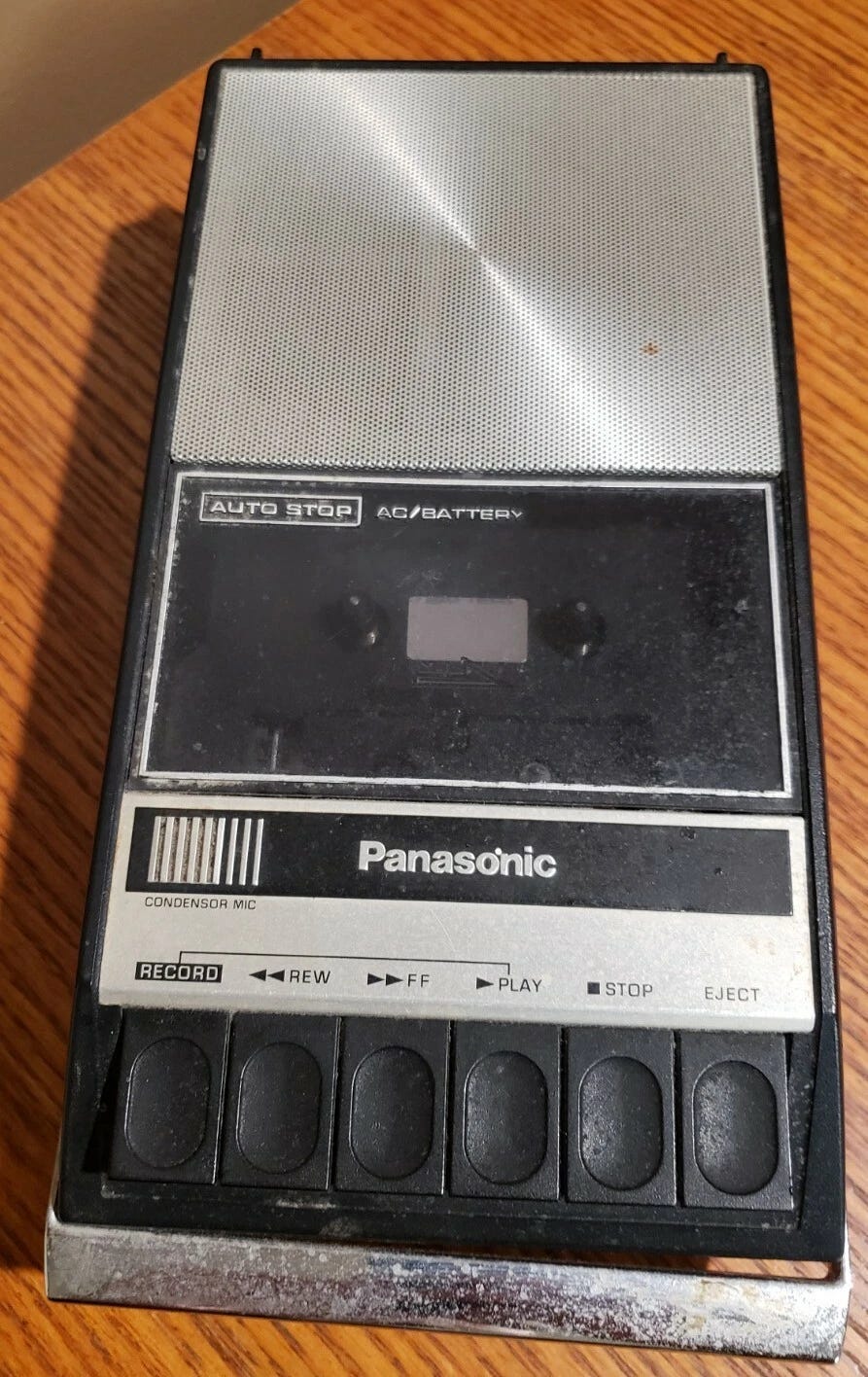

The analog age of Super 8 cameras and Panasonic tape recorders.

Before the internet became a part of our lives, day-to-day existence was different in numerous ways. A paradox of our hyper-online era is that, despite having gained a nearly unlimited capacity for human connectivity, huge swaths of the population appear to be lonelier than they ever were before. In fact, the more “online” one is, it seems, the likelier he is to be utterly bereft of meaningful relationships with others.

This worrying trend seems especially conspicuous amongst the young, particularly the younger male population. In Japan, there are reported to be perhaps a million so-called hikikomori, the vast majority of whom are young men who remain indoors all day, playing video games and engaging in other exclusively online activities.

Is the internet to blame for these baleful patterns of behavior? Correlation not being causation, and all of the rest of those boringly obligatory disclaimers aside, one certainly suspects so.

But hasn’t the internet also created conditions whereby obscure individuals can become accidental celebrities, like the “Chocolate Rain” guy, the “hawk tuah” girl, and the “Married in a year in a suburbs” goofus, among many others? Yes. The fact is that, in our time, anyone can “go viral,” given the right circumstances. And barring the achievement of actual virality— which I suppose is defined as becoming ubiquitous as a meme or something quite like it— ordinary people can amass a following of more modest but still impressive proportions (Substack being one such place).

*******************

Having grown up in the 70s and 80s, in a world where there was no such thing as “online,” I can report that things were quite different for those possessed of a creative orientation (this was before the appalling appellation “content creator” had been coined). Many of us kids wrote poetry— in my case, really bad poetry, which I still cringe to recall— and stories on notebook paper or, in our “fancier” moments, on a typewriter, with liquid paper handy to whiten out our inevitable errors.

Sometimes we used our parents’ Super 8 camera to make no-budget science fiction movies, with Lego spaceships on strings and “special effects” that, in the case of my neighborhood friends and I, included such innovative tactics as using a ball point pen to draw on several frames of the actual film to create the appearance of one character shooting another with a laser gun. John Dykstra, eat your heart out…

Most commonly, though, we used a tape recorder to entertain ourselves with our own antics. My father purchased a standard Panasonic for work, but I eventually inherited it.

As a boy, I would record things constantly. At the time, it was a wondrous device for a kid to have. You could record yourself and others (by hitting “record” and “play”)… then listen your own voices say what you just said, exactly as you just said it, immediately afterwards! All you had to do was rewind the tape, then push “play.”

Sometimes my friends and I would just goof off together, as the tape ran from the beginning to the end. Other times we would perform skits, of a sort, though always fully improvised and rather open-ended in subject matter. I would also bring my tape recorder on family trips, where I would narrate our activities and sometimes obtain exclusive interviews from other family members.

But my crowning achievement, at least as I saw it at the time, was taking that same trusty Panasonic around my elementary school when the annual “Field Day” took place, and announcing the events of the day. On Field Day, half of the school wore red (having been placed on the “red team”) and half wore white (having been assigned to the “white team”).

Naturally, some people thought I was a total dork for doing my best impression of a television or radio sportscaster, treating the small-time, grade school competitive events as if they were the Olympics. Some kids shouted into the tape recorder or otherwise behaved obnoxiously in its proximity, but I didn’t much care; I was in my own little world. It was great fun to relive Field Day a few months later, after everyone else at the school or in the neighborhood had completely forgotten it.

*****************

In the analog age, however, there were precious few occasions whereby one could share one’s work with the world at large. Sometimes, of course, one did not really have any desire to do so. A tape recording of you and your friends was generally meant for just you and your friends to enjoy; why would anyone else possibly be interested in listening to it?

But other works, like my Super 8 sci-fi movies and the short stories and (cringe) poems I wrote were projects that I would have liked to share with others. A few years later, at age 18, having becomes something of a artsy cinephile, I attempted to do a feature-length “movie” with the upgraded technology now available to me: a video camera. My intention was to make something similar to Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise, with the help of a few friends; of course, it wound up going unfinished, and its current whereabouts are unknown. It was in some ways, the very first “mumblecore” feature, fifteen years earlier, with dialogue that was mostly improvised and a character-driven plot centered around awkward human encounters.

My awful poems eventually found publication in my high school literary magazine, but other than that, none of the creative endeavors I attempted were ever presented to a wider audience. I am certainly not claiming that the world missed out by being denied exposure to my juvenilia. I only note that, in the digital age, young people have no such impediments. Written works can be posted online, on Substack or elsewhere, and videos can be uploaded on any number of outlets.

True, no audience is guaranteed; many projects posted online go relatively ignored; still, even if only 40 people watch your YouTube video or read your Substack-published poem, that’s still a bigger audience than a creative kid in the analog age would have the capability of reaching, since, again, there was no “online” at the time.

This raises another question. Are young people today better off for having a greater access to recognition and fame, as facilitated by the internet? Or contrarily, were analog-era kids like me in fact better off for having been denied that kind of exposure?

https://andynowicki.substack.com/p/how-gen-x-kids-entertained-themselves