Is Germany Previewing America’s Speech Future?

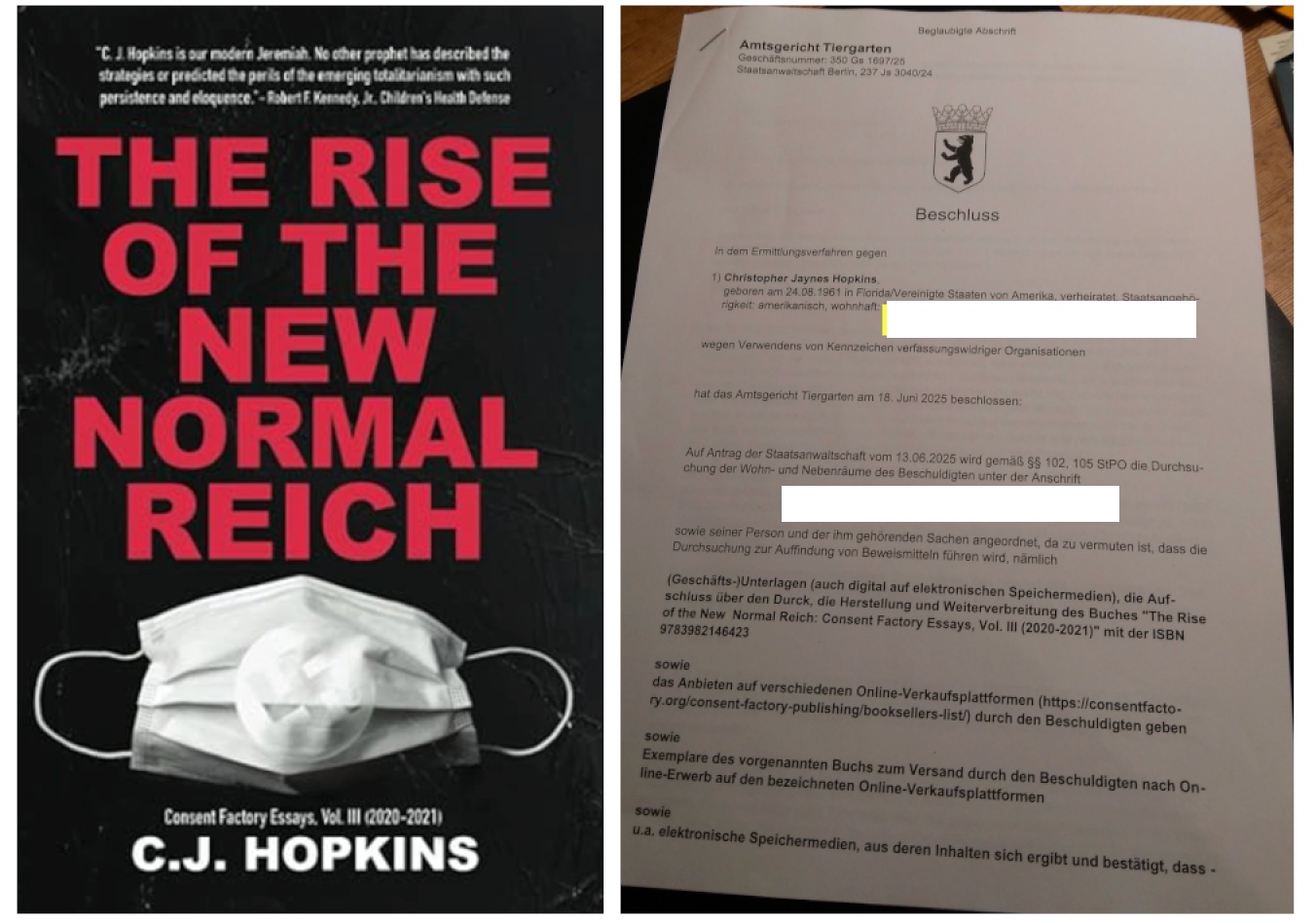

On November 26th, three armed police officers in Berlin showed up at the door of American playwright and author C.J. Hopkins brandishing a search warrant. Having already charged and issued a “punishment order” to Hopkins two summers ago essentially over the satirical use of a swastika on the cover of his book The Rise of the New Normal Reich — it’s in a white-on-white medical mask, mocking pandemic authorities — officials returned with a new theory. After questioning him and his wife, they searched the place for evidence that Hopkins is indeed the publisher of his book and the operator of his Consent Factory blog, where the book is promoted.

“Basically, distributing and promoting my book is a crime in Germany, at least according to the District Prosecutor,” Hopkins explains.

Europe made headlines yesterday by issuing a $140 million fine to Elon Musk’s X platform, but financial and political media for weeks now have been trumpeting a “digital simplification” plan that would ostensibly mean “rethinking its crackdown” on content. To spur investment, supposedly, President Ursula von der Leyen and EU officials are hinting at a less regulated tech future. Things have grown so confused in speechville that some human rights advocates oppose the plan, worried that less oversight would lead to more hate and discriminatory corporate surveillance. If it even happens, will “simplification” impact individuals, or just companies?

As C.J.’s case shows, it’s not clear changes are coming at ground level, at least in terms of policing of speech offenses. “Nothing has changed in Germany or the UK as far as I know,” he said yesterday. “If anything, it’s gotten worse.” He pointed to two other loud cases, a recent raid of Die Welt columnist and media studies professor Norbert Bolz, and the September sentencing of Bremen-based artist Rudolph Bauer to a €12,000 fine for “use of symbols of unconstitutional and terrorist organizations.”

Both cases would strike Americans as absurd parodies of police overreach. The conservative Bolz’s trouble stemmed from a tweet in January 2024, in which he poked fun at the left-leaning newspaper Taz by quoting one of its headlines. “Good translation of ‘woke’: Germany, wake up,” Bolz wrote. Taz had published a piece saluting a ban of the right-wing AfD party that contained the headline, “AfD ban and Höcke petition: Germany is waking up.”

The phrase Deutschland wacht auf recalled a line from the second stanza of the “Sturmlied” anthem, so Bolz essentially was raided for pointing out someone else’s maladroit use of Nazi verbiage. According to Die Welt, police told Bolz to “be more careful in the future” mit der joke-machen. Taz defended Bolz and, humorously, changed its headline.

The case of Bremer, a former Johns Hopkins fellow, was more war on irony. Like Hopkins, Bauer was a critic of pandemic policy, publishing articles with names like “Reason in Quarantine: The Lockdown as a Civilizational Collapse and Political Failure.” He said in a press release that police searched his smartphone and five “art books” plus “all rooms, adjoining rooms, cupboards, and drawers… including those of the artist’s wife,” and “120 linear meters of the scholar’s extensive library.” Ultimately, he was punished for three photomontages, including one that contained images of EU President Ursula Von der Leyen and Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky shown with a “black and white imperial eagle with a swastika” in between.

Germany has long been something of an outlier among Western nations when it comes to speech, as its postwar government embraces concepts like overt bans of Holocaust denial and dissemination of Nazi propaganda as essential. However, its more recently development of a system of digital surveillance and policing has created a model for a new brand of neoliberal politics-or-else.

In these procedures the lines between actual neo-Nazism and satire are blurred, and even private criticism of immigration policies or health officials might invite visits from task forces targeting hate speech. New laws continually expand the definitions of prohibited content. For instance, in 2022, Germany added to its incitement laws bans on “discriminatory statements against persons based on gender identity.” Authorities celebrated International Women’s Day in 2024 with raids against 45 people suspected of misogynistic speech.

Similar criminal speech laws have been passed in a number of European countries, and Hopkins believes images of ICE raids and boat bombings in the U.S. are helping set the stage for a clampdown.

“Unfortunately, the populists/neo-nationalists are playing into the neoliberal establishment’s hand, becoming exactly the monster they needed it to become,” he says. “And I’m afraid the inevitable backlash is going to be quite severe.”

Hopkins isn’t alone in not buying the “digital simplification” rhetoric.

“The EU is certainly not backing down,” says Andrew Lowenthal of Liber-Net, a group dedicated to mapping corporate and government censorship. “There are many more innings to go on all this.” Andrew should know, having conducted a long study of the issue:

Lowenthal should be familiar to Racket readers, having led a study that grew out of the Twitter Files.

Three years ago, while rummaging through an old Inspectors General report in an effort to learn about a State Department entity called the Global Engagement Center, I found a list of contractors and awards. It looked interesting, but 36 out of 39 contractor names were redacted. It seemed odd. What possible reason could there be for keeping “anti-disinformation” contractors secret?

In an effort to find out, we hired a team to look through public documents and try to make a count. The lead figure was Lowenthal, a longtime civil society researcher from Australia. Under his guidance, we counted hundreds of organizations and academic departments that appeared to be scoring and flagging content and/or working with platforms and governments like our own to recommend takedowns and other action. We had to stop once the number became unmanageable — the initial spreadsheet had hundreds of names — but Andrew did oversee the release of a report that introduced the topic to journalists around the world:

Andrew moved on to become Director of Liber-Net. As Greg Collard already reported, Liber-Net recently put out a huge report on censorship in Germany. That study confirms what many of us suspected three years ago, namely that the complex of organizations dedicated to monitoring speech is far bigger than we initially thought. The report “clearly indicates that there’s thousands” of censorship-directed groups, Andrew told us. “You could even get up into 10,000.” Just his map of Germany shows a broader country-level scale, with 330 organizations counted, as well as 425 speech-related grants.

Trump’s second term started off on a semi-hopeful note on speech, with Vice President J.D. Vance excoriating officials at a Munich security conference to abandon censorship policies. However, the administration’s rhetoric about Europe and speech has taken a more bizarre turn recently, with the Trump administration releasing a new National Security Strategy that predicts — threatens? — Europe with “civilizational erasure” if it doesn’t change its speech policies.

The Trump administration has since been beset with its own speech controversies, which range from a legally clumsy effort to reverse DEI and compelled speech at universities to much-debated detentions of legal (and illegal) immigrants over speech issues. The massing of military forces in Puerto Rico for possible action in Venezuela is showing up in polls as broad discontent, and some of the administration’s staunchest speech allies (like Kentucky Senator Rand Paul) have shifted to challenging it over its boat-bombing program. Whatever one’s political orientation, a gambler might start looking at what a post-Trump speech environment would look like, and the “template” of Europe increasingly looks like a solid bet. The tools for a backlash are in place across the continent (and in Lowenthal’s Australia), and it’s not hard to imagine the inevitable fulsome response in the U.S.

How might that work in practice? Lowenthal said his study shows a range of disturbing trends.

“The European Commission is now pushing for these quite invasive scans of even personal communication,” he says. “This type of censorship regime is going to be expanded. Things that are not publicly articulated, but rather messages among small groups in private or between individuals are going to be subject to the same kind of standard as a public violation of one of these ordinances.”

The Liber-Net study lists a variety of organizations that do everything from publishing general campaigns against hate speech to working openly with government to monitor and take down content. The accumulation of NGOs and grants has a long backstory, with new bureaucracies popping up to track responses to the 2008 financial crisis, then “Brexit, Trump, COVID, Ukraine, Gaza, et cetera,” Lowenthal says.

The overall picture is of a two-pronged effort. On one hand, there’s a giant complex of organizations that push educational initiatives, fact-checking, media scoring, and the like. These aren’t actively seeking takedowns or arrests, “but they do shape the overall media environment quite profoundly,” as Lowenthal puts it. These groups are buttressed however by an increasingly potent hard edge, a “whole layer of raids and confiscation of people’s computers and things like that. It’s not just losing your X account.” Fines, travel restrictions, restrictions on publication, and other penalties (and rewards) have become a type of large information-guidance system in which public money and police play a more-than-occasional role.

The overlapping roles of police, outside organizations, and bureaucracies like the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV) insert pressure and punishment at every level of publishing. Some acts are preemptive, some influence by slapping general labels on outlets, and cases like that of Hopkins and Bauer are dealt with post-factum. From the Liber-Net report:

The BfV’s annual Verfassungsschutzbericht, or Constitutional Protection Report, is essentially a public blacklist, naming groups who deviate from official policy or who publish dissenting viewpoints… The daily paper Berliner Zeitung had to contest its designation as a “pro-Russian outlet” by the BfV’s Bavarian subsidiary, ultimately forcing a retraction. The prominent journalist Aya Velázquez has also been targeted, with her articles monitored by the BfV. In another case, Compact Magazin was outright banned and its offices searched in July 2024 due to the BfV’s classification of the magazine as right-wing extremist. The private residence of editor Jürgen Elsässer was also searched.

The Guardian cheered the ban of Compact, which it described as a hub for dispensing “anti-Muslim and far-right conspiracy theories”:

When the ban was lifted by German courts, a number of English-language outlets responded with alarm, with the Times of London saying the ruling “comes as a blow to proponents of a crackdown on extremism, as the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) has surged to become Germany’s second-largest party.”

The Times also took an exacting tone with a 16-year-old who got in hot water with authorities for writing, “The Smurfs are blue and so is Germany.” Some laughed at the so-called “Smurf case,” but the Times dug deeper into the teen’s posting history:

She also released a video of herself surrounded by nationalist symbols such as runes and wearing a jacket that bore the initials “HH”, the logo of the manufacturer Helly Hansen but which could also have been interpreted as an abbreviation of “Heil Hitler.”

The concept of a society where multitudes of idea police descend from different directions into academia, media, social media, publishing, and broadcasting may not sound so foreign, since an informal version of the same thing exists in the United States. Some of it has been temporarily starved or defunded (via campaigns against concepts like DEI), but the society Lowenthal and Liber-Net catalogued in Germany is a full-service, more ineradicable version that awaits as a possible future.

“This,” Andrew says, “is what they mean by the whole-of-society approach.”

https://www.racket.news/p/is-germany-previewing-americas-speech