Just How Much Land Has Been Saved Anyway?

Absurdistan is running a 3-part series this long weekend (in the Commonwealth) connecting how ‘saving’ land means that land once available to the citizens of the country, is transferred to the banks and funds of the elites. The activists on the ground may be sincere, but their funders and lawyers are not.

For the sake of prosperity and the future, land and resources must be owned by the citizens of the nation, not traded as tokens on a block chain or bought by other sovereign countries. Since globalization kicked off, the opposite is true. Everywhere individual property rights have been weakened and in a weakened state turned over to banks, hedge funds, NGOs and ‘family offices’.

The result has been the systematic impoverishment of the lower 75% and a sharp diminution of opportunity.

More than 10 percent of the developing world’s landmass has been placed under strict conservation—11.75 million square miles, more than the entire continent of Africa.

Everyone conserves in the developing world, setting aside trillions of dollars in natural resources. In 2010, Goldman Sachs announced that 735,000 acres had been placed under conservation in Tierra del Fuego, the economy of which is based on its land: oil, gas, sheep farming, and ecotourism. You can be sure that these 735,000 acres were some of the most valuable acres in Tierra del Fuego and those resources banned from use by citizens.

In point of fact, all set-aside lands in the developing world hold valuable natural resources that could be used to create a landed peasantry, thereby moving natives out of a millennium of structural poverty, or to build hospitals, schools, and a cheap energy system for all the citizens of that developing nation. Hernado de Soto points to solutions in South America. As land there stands now, without reform, peasantry for the next millennium.

Little wonder that country people see themselves as the new persecuted class. We haven’t even begun to count the tens of millions of crushed and broken rural Americans cleared from the country, the resources shut away by the beneficent rich, the opportunities lost, the lives choked, the children who could not be sent to college, or the unfunded retirements.

The subversion of one of the founding principles of the American republic—private property—demonstrates just how productive that principle was, creating prosperity for hundreds of millions. Today’s proliferating restrictions are creating disaster for tens of millions.

Environmental overregulation is what, in part, motivated MAGA. In the United States alone, hundreds of millions of acres—more than 30 percent of the nation’s land area—have been set aside in formally restricted zones, whether wilderness, forest reserve, or privately conserved land. According to Conservation Almanac, a website of the Trust for Public Land, as of 2005, 20 percent of the United States, or 473,653,970 million acres, had been placed under no-use or limited-use restrictions. As of 2010, the count is up to 700 million acres, one-third of the U.S. land base of 2.3 billion acres. In Canada conserved or severely restricted lands are much more than 30 percent.

Most of Canada’s land is owned by its government; in British Columbia, only 6 percent of the land is privately held, and only 1.9 percent of that is available for development.

In fact, little more than 3 percent of the landmass of Canada has been developed, yet in late 2010, the country placed 150 million acres of boreal forest, an area twice the size of Germany, under strict conservation, except for those multinational forestry companies who have made deals with the American foundations and multinational ENGOs that now oversee those lands. Ownership, for all intents and purposes, has been transferred out of Canadian hands.

In February 2012, the premier of Quebec, Jean Charest, announced what he called perhaps the largest conservation project on the planet, an area the size of France, roughly 160 million acres.

And the beat goes on.

Adirondack Park – The Model for the New Peasantry

It is useful, therefore, to demonstrate what happens in a region when conservation becomes the dominant value.

For the sake of argument, we should look at the state where the American “empire” began. Keeping in mind that the third most populous state in the union, New York, in the popular imagination is generally thought of as heavily industrialized, populated, and polluted, in the greatest danger therefore of catastrophic biodiversity collapse.

This is so wrong as to be ridiculous. In fact, more than 40 percent of New York—almost 14 million acres*—is in the process of being rewilded, turned back, in all essentials, to Iroquoia. Ten percent (more than a million acres) of New York State is classed as wilderness, and another 20 percent (more than 2 million acres) is classified as forest preserve, constitutionally protected as “forever wild.”

Another 2.8 million acres is formally protected and managed by the government in various categories, adding up to 5,804,000 acres in government-managed landholdings. Acreages are not published for the 1,349 miles of wild and scenic rivers, coastal erosion hazard areas, coastal fish and wildlife habitat, and the buffers that these treasures require. Nor are the 1,251,632 acres of wetlands counted in protected areas; nonetheless, these areas are protected, and all of them have 100- to 300-foot buffers around them. Equally of the 70,000 miles of creeks and streams in New York State, all are in the process of having buffers instituted.

Wetlands in Adirondack Park add another million acres of protected wetland; the state Department of Environmental Conservation has not as of this date finished the count of protected wetland within the park. Depending on the size of the wetland, buffers can take many more acres than the wetland itself. But a rough calculation that places buffering of creeks, streams, and wetlands using a conservative 200-foot buffer (the state DEC states it wants 300-foot buffers) increases land set-asides to another 4 million acres.

The template for “living embedded in nature,” the movement’s stated, overarching goal, is demonstrated by the fate of those living in Adirondack Park under “ecosystem management,” which is the standard toward which all rural lands are heading. That tight management, allowing one house per 8.6 acres or one house in 45 acres, brings the count of acres under tacit preservation to 14 million acres. Founded twenty years after Yellowstone, in 1892, Adirondack Park was originally 2.6 million acres. Today its acreage stands at 6.1 million acres. Almost 60 percent of Adirondack Park is privately owned; in fact, much of the park has always been private land.

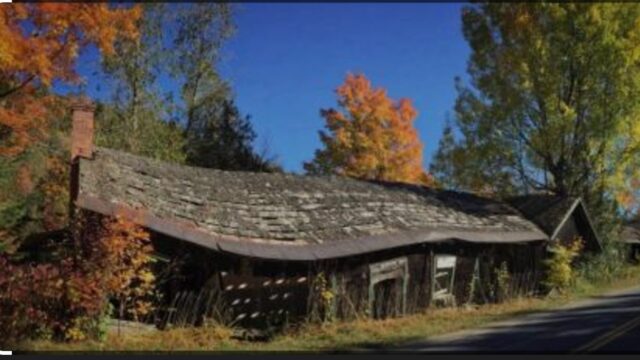

Today the park holds 103 small towns and hamlets; the 130,000 residents all live on privately owned land. As the steel net around those people has tightened, their lives have become a reversal of the accepted progression of modern life: poorer, with sharply limited opportunity and access, and older, yet with shrinking government services. Many of the mechanisms of conservation—such as greenlining, the targeting of private land for conservation—were first invented for use in the Adirondacks. Unlike Yellowstone, it had been settled by early pioneers for more than 150 years when created.

As a result, the park is the model that we are all, in one way or another, following in the creation of protected spaces that were once or are still lived upon or used by humans in some way. Management of the one hundred national monument sites in the United States, for instance, mimics almost exactly the management of Adirondack Park. In an expansion process typical with all conservation, the establishment of a staggering sixty additional monument sites were signed by President Obama and Joe Biden signed ten.

There is no procedural way to fight or stop a monument listing; it is entirely an executive decision, and once done, anyone with interests in that area has essentially been moved to the scrambling and desperate working class. In the fall of 2009, the Adirondack Park Regional Assessment Project released a report describing the conservators’ “success.” In the past thirty years, school registration has dropped 30 percent, meaning that the equivalent of one school has closed every nineteen months. Those under thirty-five leave the park as fast as their legs can carry them, but retirees replace them, and the aging trend in the park is three times the national average.

Incomes are lower within the park, lower even than those towns only partially located inside the park. Mines and mills—as forests have been gradually moved into “forever wild” status—are shuttered. No private investor dares put money into the park; as a result, as late as 2009, only three of the 103 towns had cell phone coverage, and there was virtually no broadband.

Jobs in the private sector have vanished, though until the 2008–2009 crash government jobs had increased, subsidized, of course, by the state, since local government is broke. Between 1986 and 2006, property tax revenues dropped 3 percent in the park—this during the biggest real estate and accompanying property tax boom in history.

Municipal expenses—largely driven by welfare and the costs of complying with onerous environmental regulations—are twice that of towns outside the park. Typically, conservationists promise that with forests and lakes moved into wilderness or “forever wild” status, tourism will replace lost jobs. But that never ever happens.

In 2006, Carol LaGrasse, a retired civil engineer from New York City, and Susan Allen, editor and publisher of a local Adirondack newspaper, took a walk on the highway out of the town of Wells (2000 population, 737). The couple were headed for Whitehouse, a famous ghost town in the park, first settled, as was Wells, in the last years of the eighteenth century. Whitehouse, with its two antique suspension bridges and ancient chimneys, has been a well-loved recreation area for Wells residents, who consider the settler artifacts in Whitehouse part of their cultural heritage. LaGrasse and Allen found that the main road into Whitehouse was blocked by boulders and was scheduled to be further broken up into a footpath. The culverts were to be removed by the Department of Environmental Conservation.

Old roads that led to campsites long used by the townspeople of Wells were now completely blocked. In the ghost town proper, the fieldstone chimneys were not long for the world either. “The chimneys are non-conforming under the APSLMP [Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan] Wilderness guidelines,” trumpeted the DEC. Of course they are nonconforming. They were built in the late 1700s. Until it was stopped by the town supervisor (given the vocal opposition of all the residents of Wells), the Department of Environmental Conservation planned to tear down the suspension bridges and chimneys and break up the stable sod near rivers and ponds, established by settlers and now used by those settlers’ descendants as campsites.

Old grave sites would be inaccessible to those descendants who cannot hike in. LaGrasse: Eradicating highways closes down access to the cherished places, so that descendants and local people who would like to visit, pay their respects, and maintain the cemeteries find it impossible.

the constitutional governments that emerged after the American Revolution recognized that they did not have the right to interfere with the law-abiding activities of their citizens.

And when that happened, the result was a tremendous increase in material prosperity in those countries that recognized property rights.

More harshly, the normal effort of people to show reverence toward those who came before them is squelched. Deliberately closing down access to local cemeteries … becomes a demoralizing force in the human community. It is a force of tyranny and debasement.

The Indians of North America complain of the white man building on their old sacred grounds. Nary a voice is raised against the legitimacy of these claims. When it comes to their own heritage, however, today’s conservationists are more than willing to gut their past.

Thinking on property rights has become infinitely complex over the past 250 years, but it is arguable that no conclusion has advanced further than that of Aristotle, as long as you toss out his definition of anyone not Greek as a slave who did not deserve property: “What is common to the greatest number gets the least amount of care. Men pay most attention to what is their own; they care less for what is common; or at any rate they care for it only to the extent to which each is individually concerned.”

The shift to property ownership that became institutionalized in the years after the American Revolution changed everything. Propertied individuals could not be controlled so as to make them part of a truly effective plan. This was a perfect inversion of what Washington and his associates thought—that propertied individuals were free individuals. To post WW2 planners, profit as motive would have to be replaced by a higher set of values, which boiled down to service to the community at large.

In the wider culture, however, by the 1980s, central planning had failed so many times and in so many ways that it had been largely abandoned in embarrassment. In the developing and Iron Curtain countries, where there were no constitutional democracies and no private property rights, the planning ethic could be fully realized; the results had been shown to be catastrophic.

However, lots of people felt that the higher value of community service (or Marxism) failed because it hadn’t been tried using the bounty of the West. It has been said many times but bears saying again, when the Iron Curtain fell, fellow travelers migrated to the environmental movement. And when they arrived to transform the rural world—a world few of us visit except on vacation, when no one is paying attention—they brought their planning with them. And because no one has been paying attention, the planning and control of rural areas has been adopted in countries big and small, developed and not.

The shift to inch-by-inch biocentrist command and control is one that would pitch George Washington and his associates into a state of awe at its reach. They would barely be able to grasp the fact that these new values are supposedly international and are definitely coordinated and implemented in a systematic way in many regions at the same time. And they would certainly rebel at the control these new values demand.

When the constitutional governments that emerged after the American Revolution recognized that they did not have the right to interfere with the law-abiding activities of their citizens.

And when that happened, the result was a tremendous increase in material prosperity in those countries that recognized property rights. By the 1970s, this principle was looked upon as an historical truism that no longer held value for anyone, neither the so-called developed West nor developing countries.

By 1970, planners declared that things were different now. Bureaucrats could create prosperity with government money and enforce equity through planning, accompanied by surveillance and coercion. At the time, aid money to developing countries was thought to be the magic bean that would produce the beanstalk and gold coins.

In the hypermodern superstate, property rights were “otiose.” They served no purpose and should be retired. The State must rule with an iron fist because that was the only way to create wealth and equity. There is no starker way to describe what is taking place right now in the country than as the full flourishing of the bureaucratic state.

Private property rights have been largely removed, the culture is dying, but the state, consisting of federal, state, and local ministries and departments, has bulked out so that a giant superstructure of bureaucrats with rulebooks piled high around their desks flourishes, grows, and feeds on ever-diminishing wealth.

Despite all the promotional materials to show how good and noble it is to “save” land, to set it aside or sell it to the government to be permanently protected, there is no model of communal holding of land that hascreated prosperity.

Nor is the effect neutral. Communal property ownership always creates economic malaise or worse. Nonetheless, we are still working toward that model, under which the state owns everything and permits everything. There are hundreds of ways to remove property rights without outright purchase of the land, and New York State pioneered the use of nearly all of them.

As resource use is curtailed, jobs are extinguished, service jobs fall away, families break up, tax money vanishes, and social services fade just like the Cheshire Cat’s smile. In rural counties all across the United States, sections of every forested county were once deeded as school trusts.

The proceeds from the sale of the wood from those forests would be spent by the public schools in that county. As forests are reassigned to no-use status, rural schools lose that income and are gutted. Conservers acknowledge that removing land from the tax base means government services decline because property-tax collection crashes. Many states promise something called payment in lieu of taxes, abbreviated PILT or PILOT. But PILT never replaces all the tax revenue, and it usually peters out within three years, after which tourism and that mythic beast, green jobs, are supposed to take up the slack.

In a final eerie parallel, just as the resettlement money that was promised the Indians of North America rarely showed up. In the developing world resettlement money for tribes cleared from their ancestral land by the Nature Conservancy, the World Wildlife Fund, or Conservation International rarely arrives. Conservers in the developing world and in North America point to joint nature/resource projects. Regrettably, most of these fall into the “too little, too late” category, a cruel joke to country people and Potemkin villages for the world’s press, corporate and government donors, and anyone else who asks an inconvenient question. The human culture may die, but at least the forests are protected and healthy. Right? Right?

No, they are burning, every summer, without their natural stewards, the people of the land, they die. Like the towns, schools, businesses, married to this venal land grab with a pretty face.

https://elizabethnickson.substack.com/p/just-how-much-land-has-been-saved-a06