Mastering the Machine

“There is no such technology that could rival spiritual strength. We were convinced of this countless times, this fact was proven by every unknown soldier, who had passed through all the horrors of military technology and placed his indestructible, sturdy heart on the scales. This is when it became apparent that what was important is man, not technology.”

— Ernst Jünger

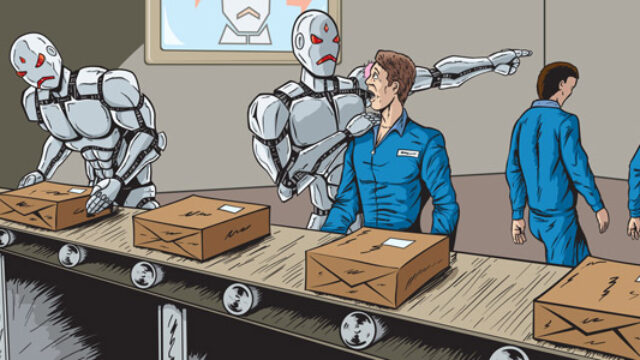

The AI boom of the past two years is now engendering a revolution in robotics. Automation has long been deployed in factories, ports, and subway systems. But today’s robotics landscape is expanding beyond these sectors. Technology capable of automating much of the service economy – from self-driving taxis and delivery drones to robot baristas – is already available. A new generation of humanoid robots is emerging that can operate alongside human workers and adapt to unstructured environments. We are at the beginning of a fundamental shift in human-machine interaction, heralded by viral videos of Unitree’s Kung Fu robots from China and clips of celebrities like Kim Kardashian hanging out with a Tesla’s Optimus robot in her backyard. Robotic companies are also feeding hype to attract investors. But the leap forward is real: humanoid robots are no longer science fiction, and will soon begin to populate our daily lives.

What makes robotization inevitable is not only technological development, but the need to maintain a functional economy in the face of ageing societies and plummeting birth rates. After the disastrous policy failure of mass migration, robots seem a much more promising alternative. Automation basically destroys the economic argument for mass migration, as population shortages can be more effectively addressed through robotics, rather than imported cheap labor.

The prospect of robotization is particularly meaningful in a United States struggling to recover its industrial muscle. Heated discussions around the new global tariffs have seen widespread acknowledgement that automation must be the cornerstone of American reindustrialization. Robotization is inevitable. But the idea of bringing back manufacturing through automation clashes with the idea of bringing back tens of millions of blue-collar jobs.

In truth, there is no prospect of going back to the past, or the socio-economic formations that characterized it. America is on the precipice of a roboticized future defined by a new type of highly skilled worker. A few or even a single one of these workers might be able to operate a whole robot factory – as in China, which has seen the emergence of “dark factories” that use almost no lighting because very few humans work there.

Globally, the national economies that master robotization will gain an overwhelming competitive advantage over their rivals. At the moment, and also for the foreseeable future, the leading nations will be the United States and China. China has already announced a national strategy aimed at dominating humanoid robotics markets, mirroring their successful approach with solar panels and electric cars. Beijing intends to invest over $1.7 billion in humanoid robot development over the next 18 months. Chinese robotics are already benefiting. Thanks in part to a favorable government aid and a robust industrial and supply chain ecosystem, Unitree’s G1 humanoid robot is available for $16,000, while comparable American models remain in development with projected prices of $100,000-$200,000.

In a recent speech at the American Dynamism Summit, Vice President J.D. Vance emphasized the critical importance for the U.S to embrace automation in order to implement American reindustrialization. One roadblock towards the realization of this vision is that even leading companies such as Boston Dynamics or Tesla still currently depend on supply chains dominated by Chinese firms – a situation which itself strengthens the case for accelerating the revival of indigenous industrial capacity.

But America’s deindustrialization also presents an advantage. Around 20% of China’s population currently works in factories; the corresponding American number is 8%. As a result, there will be less political resistance for the introduction of robots, and more opportunities for younger, “natively” automated manufacturing companies to define a new industrial culture for the new robotic era.

As seen recently with combat drones, geopolitical competition will incentivize a widespread adoption of robotization. Ultimately, countries beyond China and America will seek sovereignty over their own production of robots, powering an economy where robotic technology will become increasingly affordable and generalized. Eventually, automation will extend from manufacturing to agriculture, services, and household care. This expansion will generate social and political, and also spiritual challenges that go far beyond the question of which jobs are preserved and which are lost. Humanity faces a potential future of massive social degradation on the one hand, and a new golden era on the other. How the robot revolution unfolds will determine the shape of the future.

***

Automation opens new horizons, but not all the visions it discloses are attractive. In his influential post-war essay “The Question Concerning Technology”, Martin Heidegger already warned about the potential for encouraging a mindset of “enframing” or Gestell in which the world degenerates into a “standing reserve” of resources to be consumed. Heidegger’s compatriot Ernst Jünger, on returning from the World War I battlefields of Europe, had already made a similar observation: “Truly, the machine had taken much from us. It made our life more energetic, but it also took away its luster.”

Both authors agreed that the challenge of technology was its spiritual impact on human beings. But their conclusions diverged. Heidegger wrote from the perspective of philosophical reflection and also political disappointment; Jünger from the inner experience of the vitality of war.

For Jünger, man’s relation with technology was tragic, in the Greek sense, as the price that must be paid for glory. The First World War was the first sustained encounter between man and machine. For Jünger, “the battle of the machine is so powerful that man almost disappears before it.” Today, the same phenomenon replays itself in drone footage of soldiers running for their lives in Ukraine before being destroyed. If there is a human hand, or an algorithm behind their death, it makes little difference for the soldiers blown to pieces. But Jünger maintained that the soldiers who survived the First World War were no longer the same men. A new breed has risen, who had gained the upper hand against the machine: “During the last battles of this war, not long before our collapse, a new attitude appeared towards technology, related not to adaption, but to a will and desire to subjugate it to internal powers.”

The strength of humanity against the force of machines is ultimately a question of will. At the dawn of the thinking machine, Jünger reminds us that it is the innate human spirit that distinguishes man from machines. Humans are driven by an inherent desire for domination and conquest; desires machines don’t possess. Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, every technological development has been accompanied by apocalyptic fears, but the anti-technological argument often defaults to equally utopian views of bucolic rural life, which really existed. Nostalgia for a pre-technological paradise points to a present anxiety rather than a past reality or a future possibility.

Jünger articulates an essentially aristocratic stance that differs both from techno-utopianism and doomerism. He doesn’t reject technology, and instead insists that man must face the challenge that it poses in order to remain the master, rather than the servant, of his technological creations.

The real threat of automation is not that robots will take away our jobs, but that they can take away our souls. Our brains will grow fat, and our thinking will degenerate into platitudes. To counter this threat requires a movement from a merely technological discussion. We need to put the political and spiritual dimension of the robotic revolution on the table. Concern about automation and the impact of artificial intelligence is more than justified. Every technological advancement comes with a cost. But the alternative to paying that cost is not safety, but stagnation.

The robotic revolution introduces the prospect of a few being able to master the power of the many, but without relying on them: an essential shift from the logic in which humanity has operated since the advent of the Industrial Revolution and mass society, if not much longer. What does it mean that the strength of political forces no longer depends upon sheer demographic weight? The maximizing power that robotics brings to individuals makes it possible for humanity to pursue adventures for which only a few humans are suited, like space colonization, and more generally, a world in which highly selective small polities outperform the bloated, depersonalized post-national states.

The path for a revival of industrial demands a full embrace of the robotic revolution. But for the West to build a society that resists the flattening effects of automation requires the cultivation of a new class of human that can master the potential of technology while retaining their personal autonomy and spiritual strength. If we approach technology with an egalitarian mindset, we will only accelerate our descent into a world of sameness, softness, and stagnation. If we embrace an aristocratic vision of technology, we may harness its power to reach higher horizons. This will be the core political battle of the robotic revolution.