Nihilism in Black and White

Violence and suicide in punk rock and gangsta rap. Continued from “Hip Hop as Anti-White Kulturkampf”

The flirtation with violence which is a large part of rap’s appeal to whites is tied up with a flirtation with nihilism. In its worldview gangsta rap has affinity with early punk rock and is in some respects the black version of it, yet for that reason it also shows the differences in how nihilism tends to manifest among whites vs. among blacks.

In gangsta rap and the culture it showcases, nihilism manifests in an extroverted, active way. A man, or more often just a boy, reaches the conclusion that life as he experiences it has no meaning or purpose, that it is cold and cruel (“Cold World” from Liquid Swords by GZA), that, as Ice Cube said on the first N.W.A. record, “Life ain’t nothin’ but bitches and money.” After that, his attitude can be summed up in lines which became iconic in hip hop: “I don’t give a fuck. Fuck the world.” Like the number of blues songs which begin with “Woke up this morning,” there are endless examples of this sentiment being expressed in rap songs. In the late 90s the most popular were the two tracks on Eminem’s debut album, “Just Don’t Give A Fuck” and “Still Don’t Give A Fuck,” (he had to tell you twice in case you forgot) but he was just riffing on 2Pac who the year before had released “Fuck the World,” which combined the blues line in the chorus: “Woke up screamin’ Fuck the World!” Tupac’s rival Biggie Smalls had a song on his debut album guest starring Method Man of Wu-Tang Clan, whose chorus says, “Fuck the world, don’t ask me for shit—Everything you get, you got to work hard for it!” The debut record by Nas says, “Life’s a bitch and then you die / That’s why we get high / Cuz you never know when you’re gonna go.” A few years before these songs, the film Menace II Society, a sort of Boyz n tha Hood knockoff by the Hughes Brothers, epitomized black nihilism in the character of O-Dog, who was described in the narration as “America’s nightmare: young, black and don’t give a fuck.”

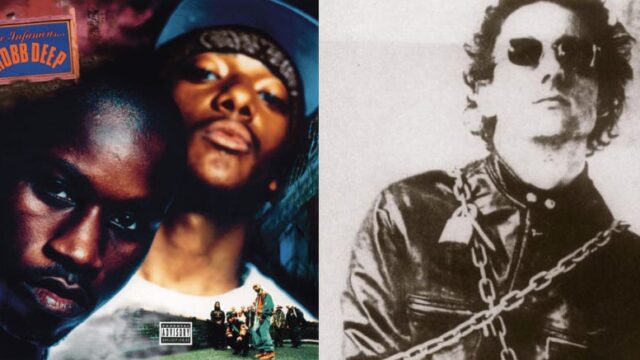

A particularly stark and compelling expression of this gangsta nihilism can be found on Mobb Deep’s sophomore album The Infamous. Of the group’s two MCs Havoc and Prodigy, it’s the latter who stands out as a gifted lyricist and performer, whose verses vividly portray the physical and emotional realities of what he calls the “trife life.” Trife is not a word in English but it would seem to be an alteration or mispronunciation of strife, as well as a variation of trifle. Taken together the meaning is clear: life is perpetual conflict and of little value. Recall that Strife was an essential concept for Heraclitus, who said that “all things take place by strife,” by the interaction and tension between opposites—hence his famous dictum, “War is the father of all.” I’m surprised some rapper hasn’t used that as a song or album title, but then most of them probably don’t read Heraclitus.

The Greeks avoided passive nihilism through what Nietzsche called a “pessimism of strength.” Their active nihilism embraced heroism and beauty, and these elements created a window for the overcoming of nihilism and the creation of meaning. Heraclitus said that “men and gods honor those killed in battle.” The moral milieu of their world did not preclude this sentiment. But the morality of late Christianity, stripped of any last vestments of Crusader knighthood, does not allow for this idea. To partake in this violent, fallen world, to do the things necessary to survive and thrive in it, is to be damned. The modern Church prescribes only meekness and passivity.

Despite the prevalence in hip hop of Afrocentrism and the ideas of the Nation of Islam and Five Percenters, African-Americans are just as trapped in a Christian paradigm as European-Americans. The NOI is quite cognizant of this and teaches that Christianity is a “slave religion” used to keep black people weak and passive, an idea which strongly echoes Nietzsche. However, at the same time, Minister Farrakhan is more likely to quote from the Christian Bible than from the Koran, and his fiery preaching style is entirely derived from the tradition of black Southern Baptists. In listening to different hip hop artists who rap about various spiritualities—KRS-One, Killah Priest, RZA, Jeru the Damaja—it becomes apparent that black Americans are searching for answers in the same postmodern spiritual void inhabited by whites. They know that they are disconnected from their ancestral traditions, and some try to actively re-embrace them, to reconnect to them (e.g. the over-the-top Afrocentric theater of the early rap group X-Clan). But there is still something missing—because you can’t go back.

The extreme of black nihilism—which I call “gangsta nihilism” since it neither applies to all blacks nor is it limited only to blacks, though it has its quintessential expression in the American urban black thug—manifests as violence and a willingness to commit murder, a total negation of the value of all life. In Mobb Deep’s “Right Back At You,” Prodigy begins by saying, “Now run for your life / or you wanna get your heat, whatever / We can die together / As long as I send your maggot ass to the essence / I don’t give a fuck about my presence.” I don’t care about my life at all, I’m willing to die just to see you die with me, because I don’t care about your life either. “I’m lost in the blocks of hate and can’t wait / For the next crab nigga to step and meet fate.” The lyrics express but do not celebrate nihilism; violence and stress become the means of warding off despair. In another song, Havoc says, “Sometimes I wonder, do I deserve to live? / Or am I gonna burn in hell for all the things I did? / No time to dwell on that cuz my brain reacts.”

Aside from the lyrics, what really makes some of the songs on The Infamous so powerful are the haunting downtempo beats which perfectly match the dark and sometimes brooding lyrics, especially on “Right Back At You” and the album’s best known song, “Shook Ones (Part II),” which was featured in the opening scene of Eminem’s movie 8 Mile and which is widely considered one of the greatest rap songs of all time. Prodigy weaves a tapestry of existential fear in his verse:

You all alone in these streets, cousin

Every man for they self, in this land we be gunnin’ …

I can see it inside your face, you in the wrong place

Cowards like you just get they whole body laced up

With bullet holes and such

Speak the wrong words man and you will get touched

If you’re white, if you grew up in a nice neighborhood where you didn’t have these concerns, it’s easy to imagine yourself suddenly “in the wrong place” on the other side of town, to imagine these words “might be about you.” In fact, the flipside of this scene, the white experience on the other side of these words, was the inspiration for another famous song: Guns N’ Roses iconic debut single “Welcome to the Jungle.” Stephen Davis tells the story in his book Watch You Bleed:

Some think the legend of Guns N’ Roses began in the nighttime Los Angeles of 1985, a distant echo of West Hollywood’s neon-lit Sunset Strip. Others think it should begin ten years earlier, at the confluence of two Indiana rivers, the Wabash and the Tippecanoe, in the 1970s. But in this telling, the GN’R saga begins in gritty New York, in upper Manhattan, on a sweltering, run-down street in the late afternoon of a summer day in 1980.

Actually it could begin way below the actual city street, in the deeply recessed concrete canyon of the Cross Bronx Expressway, which is where the two young hitchhikers from Indiana decided to get out of the car. It had been a good ride until then, a straight shot from the Ohio line across I-80, Pennsylvania, New Jersey. Bill Bailey and his friend Paul, both eighteen, had left central Indiana via I-65 thirty hours earlier and were making good hitching time toward their first visit to New York City.

The Ford Econoline van that had packed them up crossed the Hudson over the majestic George Washington Bridge. They were on I-95 now. Crossing on the upper deck, looking south, they could see the Empire State Building and the twin towers of the World Trade Center shimmering in the summer haze. Bill Bailey looked up and saw they were passing a sign that said LAST EXIT IN MANHATTAN. He said, “Hey, man. Let us off, OK?”

“I can’t pull over,” the driver said. He was an electronics salesman on his way to Providence. They were now headed east in the deep-walled pit of the Cross Bronx Expressway.

Bill asked, “Where’s the next exit?”

“Way the hell up in the East Bronx.”

The hitchers looked at each other. All they had were their backpacks and maybe thirty bucks between them. “Let us off here,” Bill said.

“Man, are you sure? It’ll be hard to get out of here.”

“Yeah, let us out.” Just then, traffic slowed into the constipation typical of I-95 as it crosses New York City. The boys jumped out. Cars honked at them as they inched along the sheer walls, looking for a way out. Drivers laughed at them, told them they were fucking insane. A trucker blasted his air horn and they jumped at the sound. The walls of the roadway were at least a hundred feet high, and all they could see were the tops of the buildings up at street level.

After a while they found the service ladder and scaled the wall, a thousand horns blaring far below, emerging into immigrant New York City, circa 1980: Calcutta on the Hudson.

To Bill and his friend, it was bedlam, a Caribbean neighborhood in Washington Heights with a funky street scene of bodegas and shouting kids playing under open hydrants, crones yelling out of windows in Spanish, idlers under shop awnings, hustlers working the corners of 177th and Broadway. Bill and Paul, from Tippecanoe County in Indiana, were the only white faces in a sea of black people, Puerto Ricans, Jamaicans, Dominicans, Muslim women in veils, Haitians, Hindus, Chinese shopkeepers, and lots of kids immediately picking up on two white boys who’d just climbed out of the hellish Cross Bronx like hayseed mountaineers in cowboy boots, blue jeans, and very long straight hair. The boys just stood and gaped, checking out this scene. “Rapper’s Delight,” bass-heavy hip-hop, blasted out of a bodega speaker. Lurid graffiti covered every flat surface. Kids were busting moves — break dancing — on the sidewalk. Bill Bailey had never seen this before. Basically, there weren’t any black people in his part of Indiana, so they might as well have been in Senegal.

Now an old man limped over to them. He gave them the once-over, seeming to linger over Bill’s cowboy boots. Bill was becoming uneasy now, his friend noticed, which was never a good thing, because, when agitated or upset, Bill’s behavior could get a little out there. Finally, the old man spoke, or rather squawked, in a high-pitched shriek.

“DO YOU KNOW WHERE YOU ARE?”

The boys, taken aback, just looked at him.

“I SAID, DO YOU KNOW WHERE YOU ARE?”

Bill Bailey said, “Uh, we’re just trying to get to…”

“YOU’RE IN THE JUNGLE, BABY!”

Bill Bailey — the future W. Axl Rose — just stared at him in wonderment. And then the little old man wound himself up to his full fury and told these white boys what they could expect from New York City at the tail end of the seventies: years of bankruptcy, endemic crime, corruption, decadence — the gateway to the eighties and the scourge of AIDS. He told it to them straight from the gut:

“YOU’RE GONNA DIE!”

Whereas the extreme of black nihilism generally manifests as violence and criminality, the extreme of white nihilism manifests as self-loathing and suicide. (I lost the reference but I saw stats confirming my hunch that suicide rates are much higher among whites than blacks.) Indeed, it could be argued that what I described above in gangsta culture isn’t really nihilism at all but egoism, the primal assertion of the self and its rights against impossible circumstances. After all, Breton said that “the simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.” What then of the drive-by shooting? Camus likewise in The Rebel contrasted the willingness of the rebel or revolutionary to commit violence against some external in the world to the suicide’s turning inward against himself, which he dealt with elsewhere in The Myth of Sisyphus. No matter how he may appear to the world, as villain or tyrant or monster, and no matter how much he may loathe himself, at some level the murderer or criminal values himself more than the world, says Yes to himself and No the world, come what may, consequences be damned.

Is there something in the white psyche or soul that finds implicit value in the world even when one’s own life seems worthless? Environmentalism as such is almost entirely a white creation. Yes, there are various non-white cultures that have an implicit valuing of nature and ways of living more harmoniously with it, but these are largely unconscious, the proof of which is these cultures’ willingness to adopt modern polluting lifestyles wholeheartedly when given the chance. Perhaps it is precisely because whites are the inventors of industrialization and hence mass pollution that ecology has become conscious in them rather than in another people. Thus it is not just environmental consciousness but environmental bad conscience, feelings of personal and collective guilt which need to be assuaged one way or another.

Nihilism and egoism once went together in the Western mind, and it wasn’t that long ago. When Nietzsche was first translated into English around the beginning of the 20th century, he was first embraced by anarchists and egoists, who were often one and the same, and this despite Nietzsche’s harsh condemnation of anarchists in his books (but then he also reprimanded Darwin and was nonetheless embraced by Darwinists, as a thinker of the same stripe, a fellow evolutionist). What’s more, Nietzsche was first embraced as a nihilist, as nihilism’s great prophet, because The Will to Power, which deals with nihilism more directly than any of his other writings, had not yet been translated into English. This was not entirely wrong insofar as Nietzsche himself said that he went through a nihilist phase and was in fact the first Western thinker to completely embrace nihilism, to take it all the way to its conclusion, and then finally to overcome it. It was a process that he knew Western man would have to go through before anything constructive would become possible.

What Nietzsche and his early egoist followers embraced could be called active nihilism—this is what Julius Evola called it in his essays on Nietzsche—which Nietzsche summarized in his appropriation of the mantra of the Assassin cult of Persia: “Nothing is true, everything is permitted.” But somewhere along the course of history in the 20th century, Western nihilism changed, became something else. In a great transvaluation of values, “Nothing is true, everything is permitted” became “Nothing is true, nothing matters, nothing is worth doing.” The excitement and violence of meaninglessness in Futurism and Dada, and to a lesser extent in Surrealism, in the egoist anarchists and others in various avant garde movements, transformed into a depression and malaise in the post-war Existentialists and the movements which followed them. The war was the great turning point, with its double crescendo of the atom bomb and the Holocaust. “After Auschwitz there can be no more poetry,” said Adorno. Suddenly, morality reasserted itself to interrogate Nietzsche’s dictum: “Everything is permitted? Even this?!” pointing solemnly at the camps and the piles of bodies, the irradiated babies crawling through the fallout. From there came a split. Only a small few dared to say, “Yes, even this is permitted,” trying to follow Nietzsche’s dictum to “Become hard.” The majority shrank away and said, “No, this isn’t what we meant, we don’t want this responsibility, we don’t want new values, give us back the old values.” But you can’t go home again, you can’t put the nihilist genie back in the bottle, and the old values couldn’t be re-embraced without causing them to mutate into something else, because they were no longer fed by the same belief, but rather by a combination of nostalgia and fear.

The punk rock which emerged several decades later in American cities was the flower of this passive, exhausted nihilism. When I put forward Mobb Deep as the best example of black nihilism, I’m taking something of a stab in the dark (no pun intended) since I don’t know hip hop well enough nor over a big enough expanse of time to know with any certainty that it’s the best example—it’s merely the best example I happen to know of. I’m also not black and hence am speaking as an outsider; I only know what black nihilism looks like from afar, I don’t even know if “nihilism” is the proper term for it. But when it comes to punk rock and white youth I feel more in my element, and more confident in saying that there is no better musical expression of late 20th century white nihilism than Peter Laughner’s “Ain’t It Fun.”

I first heard this song in the 90s when Guns N’ Roses covered it on The Spaghetti Incident. It was the standout track on the album, and a look at the liner notes revealed that GNR had gotten it from 70s punk band the Dead Boys. The Dead Boys had released it on their sophomore album We Have Come For Your Children. I didn’t particularly like the Dead Boys’ version, because I don’t like Stiv Bators, who struck me as little more than an American wannabe Johnny Rotten. Axl did it better. It wasn’t until years later, reading Clinton Heylin’s From the Velvets to the Voidoids (the best book on the history of American punk, better than the more well-known Please Kill Me) that I found out the song was written and first recorded (though not released) by a mythical, almost Rimbaud-like singer-songwriter from Cleveland named Peter Laughner.

Ain’t it fun when you’re always on the run?

Ain’t it fun when your friends despise what you’ve become?

Ain’t it fun when you get so high that you can’t come?

Ain’t it fun when you know that you’re gonna die young?

It’s such fun. Such fun.

“Laughner strung chaos and harmony on the same wire and made it quiver,” writes Greil Marcus, the dean of rock n’ roll lit crit. “The measured, suicidal cadence of the tune is terrifying.” Two years after recording the song with his band Rocket From The Tombs in 1975, Laughner was dead at the age of 24. It wasn’t exactly a suicide—acute pancreatitis brought about by years of alcohol and drug abuse—but then it wasn’t exactly not a suicide either.

“Ain’t it fun when you KNOW that you’re gonna die young?” Laughner exaggerates the know in volume and intonation, so that it becomes distorted by the cheap recording equipment and sounds monstrous. Is it so haunting because we know, in retrospect, that the singer did in fact die young? Or is it haunting because he knew he was going to die young, and this knowledge—this premonitory gnosis—infuses the performance?

Die young.—Achilles is given the choice between a long and “happy” life, or dying young and winning everlasting fame among mortals. The writer or musician who “flirts with death,” as Peter Perrett of The Only Ones sang, also flirts with immortal fame. Everyone knows that without their early deaths—by suicide—Ian Curtis and Kurt Cobain would not be remembered as they are today, with the same degree of adoration and reverence. We can imagine Cobain, alone in his Seattle flat (or not alone, depending on what theory you believe), shotgun in one hand, syringe in the other, contemplating death. Blue eyes, blond hair, handsome features, like Achilles. The Muse, the mother goddess of his imagination, descends upon him and lays out the choice: you can live, have a few more successful albums, another child if your wife can lay off the smack long enough, make a lot of money, get old and fat, get back together with the band in twenty years to do the State Fair circuit, then die from liver disease in your 70s, having just been inducted into the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame as an afterthought and a formality, the guy who wrote that “Teen Spirit” song in the 90s. Or you can die young, and be remembered forever as greater than you ever were in life.

The difference between Achilles and Kurt Cobain, though, is that Achilles died in battle. Cobain battled his inner demons and lost, yet in today’s world he is given a posthumous glory not unlike that given to great warriors in the ancient world.

“Ain’t It Fun” alternates between subdued nervousness followed by aggressive explosions of pain and anger—the Nirvana verse-chorus-verse grunge hit single formula, decades before Nirvana. It’s an emotional state of constant tension, like that of Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, filmed the same year Laughner recorded the song. It can only end in an explosion of violence, either against the world, or against the self.

Ain’t it fun when you feel that you just gotta buy a gun?

Ain’t it fun ‘cause you’re takin’ care of number one?

Ain’t it fun when you j-j-j-just can’t find your tongue?

Cuz you stuck it way too deep in something that really stung

Ain’t it fun? Such fun, such fun, fun, fun, fun, fun!

Laughner manages to rebuke both the 60s that came before and the 80s that would follow in just one verse. “Fun Fun Fun” was the Beach Boys’ hit song from 1964, which embodied the California mythos of fast cars and endless summers at the beach with light, happy verses about hamburger stands and radios blasting, and a guitar riff lifted right out of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.” It was a world away from the post-industrial wasteland of 1970s Cleveland. The idealism and excess of the 60s gave way to a lighter and mellower feeling in the early 70s, with its folk pop and yacht rock, both sounding and feeling like marijuana chased with quaaludes and cocktails. Punk was a rebellion against this boring sound, a rebellion that would eventually feed into the egoism of the 1980s, epitomized in songs like Loverboy’s “Turn Me Loose” (“I gotta do it my way, or no way at all”—an anthem for The Fountainhead’s Howard Roark) and self-help books like Robert Ringer’s 1982 Looking Out For #1. Laughner anticipates this 80s answer to 70s inertia, saying “Yeah, I’m taking care of number one, I’m on uppers, I’m doing it my way, and you know what? I’m still stuck in this shithole, my friends all despise me, and these drugs are just making me numb.”

Somebody came to me and they spit right in my face

But I didn’t even feel it, it was such a disgrace

I broke the window smashed my fist right through the glass

But I couldn’t even feel it, it just happened too fast

It was fun. Such fun, such fun. Oh, such fun, such fun, such fuuuun

Oh God

Greil Marcus:

“Oh, God”—it may be part of the song, written down, practiced until it perfectly balances the lines that have preceded it, but that’s not what it sounds like; that’s not how it feels. You hear the singer shocked by himself; you can’t see to the bottom of his disgust. You can run. You can wonder if the singer’s attitude is covering up pain or if the pain is merely there to justify the attitude, until the guitarist—the same person, you understand, as the person who is singing, just as, listening, you know he must be someone else—underlines breaks between verses with what can seem like not two but four versions of himself, too many guitars speaking different languages and no translator needed. He pounds at his guitar, making noise that shoots in all directions, to escape this moment when life has doubled back on art and killed it. He hammers away at a fuzztone, again and again, convincing you he’s said all he has to say, all there is to say. Then he steps into a gorgeous, stately solo, a work of art within this small, chaotic incident, and you can picture him holding his instrument like Errol Flynn held a sword.

After punk rock, the active nihilism that sometimes informed the heroic ethos in ancient times was relegated to heavy metal and hard rock, not unlike the way heroic tales were relegated to genre fiction. A song like Bon Jovi’s “Blaze of Glory” from the Young Guns 2 soundtrack invokes essentially the same ethos as that behind the death of Achilles, but precisely because the song was a mainstream hit single, who would notice this? And even if you notice, so what? It’s just another slogan now, destined to become a jingle for a steakhouse commercial, or maybe for euthanasia. “Death or glory, becomes just another story” as the Clash sang. The difference between Iron Maiden and the Clash is the difference between Ernst Jünger and Dalton Trumbo or Henri Barbusse, the celebration of the heroism that war makes possible versus the lamentation of the devastation and misery that inevitably accompany it.

As my friend Faisal Marzipan recently pointed out on X, it was precisely during the decline of heroic metal and hard rock brought about by grunge that gangsta rap began to rise, to fill the void and the need for music that speaks to these universal feelings of violence and bravery.

https://semmelweis7.substack.com/p/nihilism-in-black-and-white