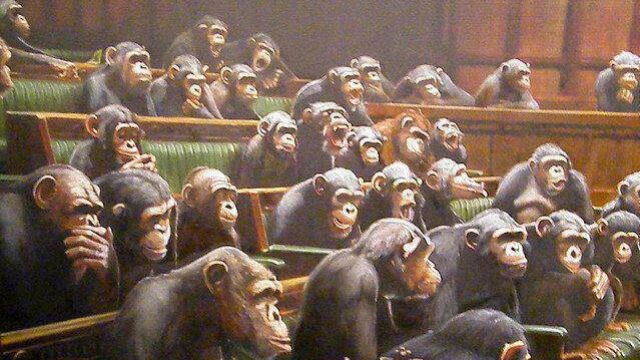

Oligarchy of the Unfit: Governance in the UK

The UK has a severe structural crisis in leadership: each of the two main parties have defects that do not usually occur in tandem, but, when combined, are highly destructive. Each is oligarchic, not democratic. But, in contrast to most oligarchic regimes, each lacks the benefit of stability usually associated with oligarchic regimes — in other words, each are also extremely unstable.

Their oligarchic nature deprives each party of legitimacy with the broader electorate.

The instability derives from organizational defects which set each party literally against itself, and, once in power, sets the Government against itself and the other MP’s of the governing party. This explains, in part the vacillating and ineffective leadership UK governments have shown in recent years or in times of stress.

A close examination of the electoral and organizational structures of the parties shows the wide gap between the U.S. system and the British system. From a British point of view, a difference from the U.S. is not always viewed as bad. However, the “gap” here is in something crucial: elections. From an American point of view, there aren’t any.

Instead of “representative democracy, the term “oligarchy by quango” (with each of the parties’ central administration being the “quango”) might be a better descriptor. In fact, an American might justifiably conclude that elections for Parliament are far less democratic today than in the times of Henry IV or Charles I.

Structural Instability. Each party has, to an American eye, a (I) bizarre, convoluted, and highly centralized method of local Parliamentary candidate selection; and (II) since 1980 (in the case of the Labour party) and 1998 (in the case of the Conservative party) Parliamentary party leadership selection: namely, the Parliamentary leader of the party (think Tony Blair, Boris Johnson) is selected not by the Labour or Conservative members of Parliament but, rather, in each case by a vote of the “members” of the relevant party at annual conferences or special elections. Thus the situation could easily arise (and has recently arisen) where the elected head of the Parliamentary party — the Prime Minister, if in government, the Leader of the Opposition, if out of government — could be despised by a large majority of his or her “fellow” Parliamentary party members. The spectacular destruction of Corbyn, nominally the Parliamentary party leader from 2015–2017, by his own Parliamentary party and the Labour central executive at Southside or Brewers Green (take your pick),1 is a glaring example. This goes to the “war against itself” point.

However, the main issue is that none of these actors are elected in any meaningful sense. So much for “much representative democracy”.

Oligarchy. Stunning as it may be to an American, the UK voter at large has virtually no say in the selection process of Labour and Tory candidates or party governing officials. Unlike the U.S., where (in the old days) there were locally organized caucuses which morphed into (in the now days) full scale primary elections, the local voters, even by representation of intermediary bodies (e.g., the state legislature, or, in the UK, local councils) have virtually no say. The bottom base of each party is not, as in the U.S., those members of the voting public that identify on caucus or primary day (or a few months before via registration) as a Republican or Democrat and can number in the millions or tens of millions. Instead, it is comprised solely of the “membership” of each of the two parties. Becoming a member is not an easy process. It is quite a bit like the process of admission to a good lunch club. Roughly speaking, “candidates” for membership in each of the parties are proposed by the local constituency but are approved only by the central party leadership in London. (For the Labour Party, see Rule Book, Appendix 2, Section 1 A. and C. Labour Party Rule Book [skwawkbox.org]. For the Conservative Party, see Section 17.7, Part IV, of the Conservative Party Constitution (amended through 2021), Conservative Party Constitution as amended January 2021.pdf [conservatives.com]). This membership, so selected, has for most of the history of each party, been a miniscule fraction of the population of the United Kingdom. The Labour party currently boasts about 550,000 members and the Tory party about 350,000 members — a total of 800,000 members for the two main parties that comprise most of the seats in Parliament, compared with a potential UK voting public of 32 million that turned out in the 2019 general election.

Even if these members, through so-called local “constituencies” could freely select their candidates, about 2% of the full potential electorate would be choosing the candidates. In a sense, one could say that these constituencies “represent” the great voting public of the U.K. in making party selection. As a comparison, even at its most restrictive, in the 1790’s, the United States permitted (via property qualifications and the like) about 12% of its electorate to vote — directly for the House of Representatives, and indirectly, through popularly elected state legislatures or the Electoral College, for the United States Senate and President, respectively.

But that is not the half of it. In fact, the constituencies cannot freely elect candidates. Since the candidates themselves are also subject to central party approval, no one even gets to run before a constituency unless pre-approved by London Central.

And even if the constituencies were able to freely elect any candidate of their choice, since none of the constituancy are elected by the greater voting public, but are chosen by a “lunch club” admission process, one could hardly call candidate selection “democratic” in any case.

Due to the membership selection process, one can see that the idea that anyone could be a member — so that, in theory, millions could pack the membership rolls and democratize the process — is unrealistic. Careful selection procedures ensure no risk exists that the rabble holding distasteful opinions will be admitted .

To make things worse, each member, once admitted, is subject to expulsion by the central authorities of the party for violating the vague specifications set out in the governing rules of the parties.

In detail, the structure each party, described in seriatim, appears to work as follows.

Labour.

Until the “reforms” instituted by the Right Honorable Sir Anthony Litton Blair (aka, at his own surprising wish, “Tony”) as leader of the Party starting in 1997, the previous method of party control giving the Trade Unions a virtual veto was changed to reduce significantly the role of organized unions.

As currently constituted, after Blair’s reforms, the Labour party is no more democratic, but, from the capitalist point of view, is in better shape since it is subject to less direct Trade Union control.2

The party is an unincorporated association governed by a “Rule Book”, see Labour Party Rule Book (skwawkbox.org) that, in turn, sets forth in 15 Chapters the “Constitutional Rules” of the party. Id. Appended to this as part of the Rule Book are nine Appendices each with, one presumes, sad to say (given their contents), the force of the main body of the text.

The Labour party has the crippling defect that (I) the head of the party is technically a separate position from that of head of the Parliamentary party and (II) the head, the Executive, and the National Executive Committee to which the Executive reports, the National Committee, are not selected by the head of the Parliamentary party or by the Parliamentary Party leader, but partly by the Annual Conference vote (theoretically at least the members at large of the party) and partly by certain interest groups (such as trade unions) and the Parliamentary wing of the party. The Parliamentary wing of the party comprises a minority on the National Committee. One might almost point to a new Constitutional concept when Labour are in power: “King in Trade Union”.

Tory.

The organization of the Tory party — technically “The Conservative and Union Party” — is somewhat less at odds with itself than that of the Labour Party but is, nonetheless, baroque.

The Constitution of the Conservative Party, as amended through 2021 (the “Tory Constitution”) provides for what appears to be a dual leadership structure.

The “Leader” of the Tory party (a) must be a member of the House of Commons but (b) is elected by the members of the Conservative Party in accordance with the provisions of “Schedule 2” of the Tory Constitution. When so selected, he is the Prime Minister when in office; out of office, the leader of the opposition. His principal duty is to “determine the political direction of the Party having regard to the views of Party Members and the Conservative Policy Forum.” Tory Constitution, Part III (Section 11).

The selection of the Leader operates via a behind-the-scenes process, although less “behind the scenes” than it used to be. Since 1998, the so-called “1922 Committee” — so named since it first formed in 1922 to defeat the incipient Leadership candidacy of the unfortunate Nathanial Curzon, then Foreign Minister and formerly (and famously, the Viceroy of India) nominates pursuant to its own procedures a slate of nominees — or only one nominee, if it wishes — for the position of Leader. This slate is then put forth to the Conservative Party membership for a vote, and possibly a run-off vote if no candidate achieves a majority on the first round (Tory Constitution, Schedule 2).

Historically, before 1965, the Queen selected the party leader, presumably with the informal advice of party “grandees”. From 1965–98, the parliamentary party controlled. From 1998 to now, the parliamentary party runs ballots until down to the last two; then the last two go to the party members. But the “last two” rule is per the 1922 Committee rules, which can be changed. It would seem under the Constitution that the 1922 Committee could bypass the Parliamentary party members totally and just directly propose a slate of 2, 3 or more. It could also change its rules so that the Parliamentary MPs names which the Parliamentary MPs would be whittled down, say, to 5. The candidate receiving more than 50% of the vote becomes Leader (Tory Constitution, Schedule 2). It is notable that, although the slate is all of the MP’s selected by “establishment folks” (who are also MP’s), the vote among the candidates is made by a membership some — or in an extreme case — all of whom are not even resident in the United Kingdom and are not UK citizens (Join Us | Conservatives Abroad). One wonders if the Right Honorable Rushi Sunak, the previous Leader and “one-year” Prime Minister, could have better spent his time recruiting his fellow Gujaratti Indians in the northern subcontinent of India for Tory Party membership, since those in the UK don’t seem interested. After recruiting a couple hundred million of those (with Hindustani translations on the ballots of course), he could remain Tory Leader for the rest of his life. He would of course have to tweak the Constitution to provide that the current Leader must always be included on the 1922 Committee’s slate.. But with 200 million adherents….

The Leader, in turn, selects the “other” head of the Conservative Party — the “Chairman” of the Board of the Conservative Party. The Board is the supreme ruling body of the Conservative Party. It consists of 19 members, none of whom is the Leader. The Leader selects at his own discretion 3 members of the Board: the Chairman (above), one of the two Vice Chairmen, the Treasurer of the Party (who serves as an officer of the Party and as a member of the Board). In addition, the Leader (a) selects one other person, subject to the approval of the Board and (b) has the right of approval over an additional person selected by the Board, giving the Leader the right to appoint three members and to have a say in the appointment of two more, for a total of five members. The other members are the Chairman of the Conservative Party Conference, elected by the Membership (he serves as the other Vice President of the Party), the Chairman of the 1922 Committee, the three Chairmen of the English, Welsh, and Scottish Conservative Parties, respectively, and the Chairman of the Conservative Councilors Association. In addition, a member of the Tory party staff is selected by the Chairman of the Board. So, essentially, the Board is effectively outside the control of both the Leader and the Parliamentary conservative party. It is this confusing edifice that has the power of both candidate and membership deselection.

The Board crucially has, under Section 17.7 of the TC, the power in its “absolute discretion” to accept or refuse the membership of any prospective or current member. The power to “refuse” membership to a current member presumably is a roundabout way of saying the Board has the power to kick out any person from Tory Party membership it wants to, including, presumably, sitting members of parliament. If that weren’t enough, the TC rubs it in your face. Under Article 17.22, it has the power over “[t]he suspension of membership or the expulsion from membership of any member whose conduct is in conflict with the purpose, objects and values of the Party as indicated in Part I Article 2 or which is inconsistent with the objects or financial well-being of an Association or the Party or be likely to bring an Association or the Party into disrepute.” Well, that’s a lot of discretion!

Under Article 17.5 of the TC, the Board has the power over “the maintenance of the Approved List of Candidates in accordance with Article 19.1 of, and Schedule 6 to, the TC (Article 19 substantially simply refers to Schedule 6).

Under Schedule 6, Sections 14–21, the Board — like its Labour Party counterpart — incredibly has the power to “withdraw” associations — that is, local conservative party constituencies — from membership, thereby disenfranchising all of the members of the local association unless the Board decides otherwise. Schedule 6, Section 20. In other words, vote the wrong way, propose the wrong candidates, say the wrong thing, yer out, Jack!

The local Conservative “Associations” are no better. The model rules, attached as Schedule 7 to the TC, state that

[t]he Officers of the Association may move before the Executive Council the suspension or termination of membership of the Association of any member whose declared opinions or conduct shall, in their judgment, be inconsistent with the objects or financial well-being of the Association or be likely to bring the Party into disrepute. Similarly, the Officers may move the refusal of membership of the Association for the same reasons. Following such a motion, the Executive Council may by a majority vote suspend, terminate or refuse membership for the same reason. (Emphasis added.)

Good God. Even the toniest lunch clubs in New York do not have such discretion to decapitate members.

DISPOSING OF A LEADER

In getting rid of a leader who is Prime Minister, there are two ways: Parliamentary and Party.

The Parliamentary method is for the Parliament as a whole to vote, apparently by bare majority, that “the Parliament has no confidence in Her Majesty’s Government”. In such a case, there are 15 days in which the existing Parliament can try to find a new government. If not, a General Election is held.

The second is for the party itself to hold a vote of “no confidence” in the Leader (not the whole government). In the Tory party, 15% of the Tory members can petition to have a Leader no-confidence vote. In that case the vote is by the Tory Members of Parliament (not any other Tory party members) only. If the PM loses, a party election (by party members, not the parliamentary members) for a new leader. However, apparently under current rules (of the 1922 Committee?), there are preliminary ballots among the Tory Parliamentary party members only (of the whole House, not just the 1922 Committee). Once the ballot gets down to the final two, a choice between the final two is then put to the Tory party members at large. If the PM wins, no more “no confidence” votes are permitted for a year.

In the Labor party, there is no such thing as a vote of “no confidence” in the Leader. One challenges a sitting leader by mounting a candidate to oppose him. If that candidate gets 20% of the PLP (Parliamentary Labour Party ) membership to support him (note that this is higher than the 15% threshold required for a non-removal election), the contest is on, pursuant to rules to be jerry-rigged by the NEC (National Executive Council) of the party. Which could be anything. There is a lack of clarity as to whether the incumbent can automatically run, or must meet the 20% threshold in terms of PLP member nominations. If the latter, a leader like Jeremy Corbyn could be unseated easily, because he probably would not get the requisite number of PLP member nominations, even though, if ON the ballot, he might win by a Corbynist margin of say 57% to 20% to 13% — a crushing victory among the Labor party membership. (Corbyn in his initial run got the requisite 20% support on a fluke, mainly from members that actually supported other candidates but assumed he would lose but split the vote in an advantageous way.) When Corbyn was challenged, barely a year into his leadership term, he obtained a ruling from NEC (which apparently by 2016 he controlled, even though he did not control the Executive Director (McDougal) who actually runs Southside) until 2018 when McDougal was replaced (even his replacement we now know worked against Corbyn) that the incumbent had a right to be on the ballot without meeting the 20% threshold, so Corbyn did not have to do what for him at that time would have been the impossible — namely, get the 51 MP’s necessary for a 20% endorsement. This ruling has now been affirmed by a High Court ruling that now stands as substantive law effective even in the absence of an NEC ruling to that effect. [1]

Even with the incumbent’s right to run, this is madness. It means that — as literally was the case with Corbyn — that a Leader could be elected by the members of the party at large (a) that only 20% (or less — see below on Corbyn) support and thus (b) whose leadership could be easily challenged and subjected to re-vote at a new party conference almost on a continual basis. Effectively, after Southside had “deselected” enough Corbynist Labour Party at large members, this is exactly what happened to Corbyn. See “What role should party members have in leadership elections?.”

DESTRUCTION OF CORBYN

So, with this as the background instability of the system, it is easier to see how Corbyn was destroyed and how, now, the former leader of Labour is no longer even a member of Labour.

However, the particular details of Corbyn’s demise can be traced in good part to his naivety and weakness.

Weakness. His weakness was that he was hated by almost the entire membership of the PLP’s — the Labor Party MP’s. In a normal year he would have been able to secure, at most, say 5% of the PLP’s — 15 points short of getting on an uncontested ballot for Leader. However, for a number of later-to-be-regretted tactical reasons involving other candidates, a number of his Parliamentary adversaries endorsed him despite despising him — enough to get him over the 20% threshold.

Having thus gotten on the ballot by pure luck, the Party membership — clearly, completely out of tune with the MP’s “representing” them — elected Corbyn by a crushing majority at that year’s Party Conference. Suddenly this reviled backbencher was Labour Party Leader!

Naivete. For reasons best known to himself, former GMB executive, Toby McNicol, who at the time of Corbyn’s ascension to the leadership of the Labour party, held the extremely powerful position of General Secretary of the Party, despised Corbyn. McNicol did not wish to serve under him. Accordingly, McNicol offered to resign (again, for reasons known only to himself — perhaps a last trace of English gentlemanliness). This was a huge gift to Corbyn and a huge “own goal” for the “New Labour” Parliamentary Labour Party establishment. Had Corbyn accepted McNicol’s resignation and packed the Labour Party executive with his own people, Corbyn might still today be Party leader. However, unbelievably, Corbyn did not take up this gift — he refused. So Corbyn’s sworn enemy — McNicol — remained as General Secretary.

The result was that the Labour Party executive at Brewer’s Green, then moving offices to Southside, continued to be occupied by either New Labour bureaucrats or others — like McNicol — who apparently hated Corbyn just as much as McNicol. Since, as noted in numbing detail above, the Party executive has the enormous power of selection and de-selection of candidates and entire constituencies and the power within extremely broad guidelines to set the terms of any leadership election or challenge, this was an enormous “own goal” on Corbyn’s part.

From that moment on, McNicol and the New Labour apparatchiks at Brewer’s Green worked as hard as they could to unseat Corbyn, as did the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP), which, of course despised Corbyn as well.

The first result came in 2016 shortly after the Brexit vote. The PLP demanded Corbyn resign. When he refused, a meaningless “vote of no confidence” was held by the PLP, which, predictably, Corbyn lost be a huge margin. Then PLP member Owen Johnson then got the requisite 20% of the PLP to endorse his challenge to Corbyn.

McNicol used every trick in the book to trip up Corbyn via the broad discretion granted the NEC in the Labour Party rule book.

First, he convened a meeting of the NEC without informing Corbyn that it was for the purpose of making a determination under the Labour Party rules that Corbyn, like any challenger, needed to get endorsements from 20% of the PLP to appear on the ballot triggered by the challenge. This would have forced Corbyn out, since he would have been unable to obtain that many endorsements. However, the Labour unions as a block voted with Corbyn, resulting in a rejection of that proposal. Although the Executive sued to reverse the NEC ruling, the ruling was upheld by the High Court. See above.

Second, McNicol convinced the NEC to disqualify any Conference Labour Party (“CLP”) members joining within the last six months. The result was to disqualify about 20% of the CLP, most of whom were the late-entering Corbyn supporters. The power of the NEC to retroactively disqualify the voting rights of these members was upheld by the Court of Appeal, after first being rejected by the High Court. See above.

Notwithstanding these maneuvers, Corbyn won a crushing victory among the general membership and retained his leadership position.

Having failed to unseat Corbyn through “behind the scenes” rule jiggering, the PLP, and the press (who also hated Corbyn) formed a new line of attack. Corbyn had always been a strong supporter of Palestinian rights and a critic of the Israeli occupation of the west bank. This, and his statements in support of this position were dredged up as evidence of “anti-Semitism”. Since the Party had foolishly made a rule prohibiting any Member from “anti-Semitism” — whatever that was at any given time — accusations of “anti-Semitism” could be deadly for any Member, including Corbyn. At first, the Party did not accuse Corbyn directly; rather it attempted to de-select a number of Corbyn’s senior party supporters

As Chris Willimson describes, instead of rejecting these claims out of hand, Corbyn weakly agreed to punish a couple of Party members attacked and agreed to a commission of inquiry to look into these claims. Of course, the commission would be staffed by the very Brewers Green apparatchiks, including Toby McNicol, who hated Corbyn. Predictably, this commission was used to smear Corbyn. In addition, it was used to deselect not only many of Corbyn’s few supporters in Parliament, but to deselect entire constituencies whose statements the Southsde folks did not like, essentially throwing out of the party anyone who supported Corbyn. This deslection process continued long enough that, by the end of 2019, Corbyn had been fatally weakened in the CLP itself.

So instead of accepting McNicol’s resignation, bringing in a Corbyn supporter at the head of the party, and then ruthlessly expelling from Brewer’s Green its current employees and replacing them with Corbyn supporters, Corbyn now faced a Labor Executive dead set on destroying him through endless “anti-Semitism” hearings.

Notwithstanding all this, Corbyn managed to fend off these attacks to come closer to a Labour victory — in 2017 — than any leader since Blair. However, after losing the 2019 election, and bloodied beyond belief by the PLP antisemitism war, he resigned as leader under duress. Very promptly he was literally “deselected” and thrown out of the party, despite being one of the longest serving labor MP’s then in Parliament and having served as its leader since 2015!

Some have blamed Jewish power exclusively for Corbyn’s downfall. However, although Jewish power may in some sense be blamed for Corbyn’s political demise, the bizarre structure of British politics, in which a man wildly unpopular among the PLP could become leader of the Party due to support by members paying 3 lbs each for the privilege, plus his own naivety and weakness, played even greater roles.

The Sad Conclusion: Support for Israel and Mass Immigraiton by Both Parties

But the implications for the desiccated state of Britain’s vaunted “mother of Parliaments” and its elective representative government albeit under a Monarchy, are dire. The people who clearly approved Corbyn have no say. Those who do “have their say” are immediately thrown out of the party. The result is that, when the 36 million-strong UK electorate gets to choose, they get to choose between two candidates who (a) slavishly support Israel and (b) slavishly support massive immigration, even though polling indicates each of these objects of elite affection are wildly unpopular.

So, no, it’s not “all the Jews’”. But any time you set up a system so centrally controlled — whether it is with the Tory or Labour parties, BBC, or CBS News, the chance that a small set of anti-social conspirators seize the levers of power for their own ends approaches 100%.

If the conspirators simply want money, then you lose money.

If the conspirators want to destroy the people itself, then the result is the destruction of the country.

That’s where you all are “English-folk”.

_______________________

1/ Brewer’s Green — apparently not Southside — was the labor central party HQ in 2015. From April, 2012 to December, 2015 the Labor Party hq was at Brewer’s Green. From December, 2015 to early January, 2023, it was at 105 Victoria Street in Southside, hence called familiarly “Southside”. See Labour Party headquarters (UK) – Wikipedia . From January 2023 to today, it has been at a series of two addresses in Southwark — not Southside. Confusing? Well, might as well have confusion of addresses to match the confusion in the Rules.

2/ From 1900 to 1978, new leaders chosen by parliamentary party. In 1978, an “electoral college” method put in, with 1/2rd members, 1/3rd trade unions, and 1/3rd parliammentary members. That apparently lasted until 2014, in which it went to [all members?} Well it is parliamentary MP ballots to get to the top 5, then those 5 go to the party members. That is how Corbyn got through because he was 5th out of 5 on the MP ballot, but then won the party members hands down.

[1] Nunns, Candidate, at 323 (no citation), OR Books, 2016. Foster v McNicol and Corbyn, High Court of Justice Queens Bench, Neutral Citation Number: [2016] EWHC 1966 (QB) (July 28, 2016). The High Court made a substantive ruling that the incumbent need not get any nominations; it did NOT simply issue a ruling affirming NEC’s ruling on either of the grounds (a) that the NEC was the sole judge of the rules or (b) that in this case the vote of the NEC was “reasonable” interpretation of the rules. Ibid. Accordingly, the High Court decision stands as a substantive interpretation of the rules that will bind further decisions of the NEC until if and when the underlying rules are properly amended by vote of the membership. Note that the court, noting that the Labor Party is an unincorporated association bound solely by a “contract” — namely the Rules — ruled on this as a normal interpretation of contract case. Id. Note, in Evangelou v. McNicol, the Court of Appeal (Civil Division), on Appeal from the High Courts of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division, Neutral Citation Number: [2016] EWCA Civ 817 (August 12, 2016), held that the NEC did have the power to retroactively disenfranchise all constituency members who had joined the party within a period of six months before the date of the NEC ruling, thus disenfranchising about 130,000 new Labor Party members from the vote.