On Suffering, and the Sham of ‘Self-Help’

When you say that you are lost, buried, pummeled badly, in wretched shape, that you are unlikely to recover, that you will soon perish, that nothing shy of a miracle could possibly save you, you are seldom believed. People think you are merely being grandiose and melodramatic.

Or worse, you are believed, and they ask, or more commonly command, that you “get help.”

There is an unspoken presumptuousness in the invokers of “help”-reception, which I have grown to find deeply galling. First, there is an unearned presumption in the notion that said “help” even exists at all. (By that I mean, “help” that is truly helpful, not as is unfortunately more common, “help” that advertises itself as helpful, but in fact isn’t.)

Then there is the presumption that someone in need of help wouldn’t already actively be looking for it. Think of someone who endures chronic, crippling pain. Does one not presume that a person who suffers in this manner wishes to find relief? Yet somehow a person who suffers psychically is presumed not to know that psychic pain feels bad, and that he therefore needs to be told to seek out that which might ameliorate, or at least reduce, his suffering.

Thus the non-sufferer presumes to suspect that the sufferer is simply malingering in some manner, or that he must obtain a perverse pleasure from wallowing in his misery instead of attempting to find relief, the way that Dostoyevsky’s “underground man” narrator speaks of a man self-indulgently moaning over a toothache. Of course, malingers and wallowers do exist, but the default presumption that the sufferer is really just one who feigns his suffering to gain attention mostly has the effect of pushing genuine sufferers to conceal their misery, as they grow increasingly weary of being treated with default skepticism or patronizing unctuousness.

More often, however, the sufferer conceals the reality of his suffering for a simpler reason: he doesn’t wish to make a spectacle of himself.

Unlike the malingerer, the sufferer opts to cultivate a degree of stoicism about his circumstances; much as he may feel tempted to “rant” at times, he knows that indulging such impulses provides no real benefits. Once one is done ranting, after all, nothing has truly changed; one’s problems are just as present as ever before; if anything, one is in a worse state of upset for having willfully re-familiarized himself with that which causes him pain, trauma, and humiliation.

There are some, of course, who seem to relish “kvetching” about their problems. This species of person, the kvetcher, embodies an entirely different mindset, one that I find not only foreign, but positively alien, to my own.

***************************************************

Under normal circumstances, I take special care to avoid talking about my problems. If directly asked, I will reflexively deflect and subtly but deliberately change the subject. I do this in part because I strongly suspect that the asker doesn’t really ache to know the answer; he merely asks the question as a sort of social nicety. But I also refrain, as explained above, due to the knowledge that often the interlocutor in question will care, or at least will flatter himself in presuming to care, and will attempt to “help,” or at least flatter himself in presuming that he is attempting to help.

Often, I’m afraid, such “help” is mere busybody bluster and unctuous twaddle. It is a means of ego-driven self-aggrandizement of the sort undertaken by those want to make you into a “charity case.” There is a certain arrogance, after all, in even presuming oneself to be a person who is fit to help another; still more to demand that another take his (unasked for) counsel, or be deemed insolent on account of his refusal to do so.

Moreover, and perhaps more egregiously, there is a stinging effrontery in the very presumption that you are “sick” while they are well, that you are “broken” while they are all together, that you need them to cure or fix you. Such an understanding is insulting, not because people don’t get sick in mind or broken in spirit, but because it fails to respect that, when it comes to mental, spiritual, and even physical health, all of humanity is on the same continuum. That is to say, everyone is sick or broken to some degree, some more than others at particular times; such is our shared condition.

Therefore, the approach all too often found attitudinally, even among many of those who claim affiliation with the mental health field, and certainly among many of those most eager to render specious counsel to the ailing, the wretched, and the low in their midst, is ultimately dehumanizing in effect, because it does not recognize the abovementioned continuum, a continuum whose full implications are expressed in the famous adage, “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

*********************************************************

One seldom thinks of the inverse of this adage, of course: “Here, bereft of the grace of God, I go.” One doesn’t ponder this adage-reversal, that is, until one finds oneself seemingly psychically sheared of the grace that one previously presumed himself to have been granted. Then, one truly knows what it is to be the sort of person whom the supposed “fortunate ones” look upon with mingled pity, scorn, and contempt.

To feel oneself stripped of grace is to know oneself as having been flung into the pit.

Finding oneself flung headlong into this fearful aperture is a shock at first, and major shocks are typically accompanied by a sensation of disbelief. The circumstance never ceases to seem surreal, because one never seems quite able to become adjusted to the conditions which prevail in the pit. Misery cannot cease to be miserable, regardless of how familiar it becomes.

As with the souls in Hell, fresh assaults of disorienting trauma continue to pummel the sufferer’s consciousness. Indeed, the pit, like Hell, is a state to which one cannot inure oneself. The only difference is that while Hell is forever, time in the pit is merely temporal.

Of course, that which is temporal isn’t always temporary. Sometimes it may even last a lifetime, as many a pit-dweller can attest.

***********************************************

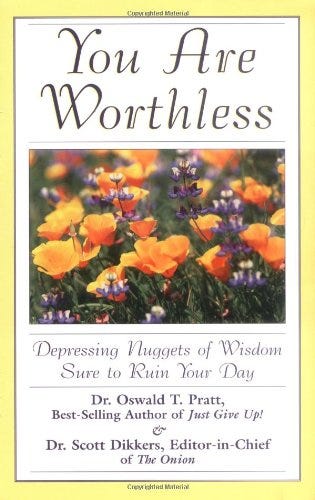

There is a notable glut of self-help books available today.

I’m sure that some of them are, in the main, inoffensive, and a few might even contain the odd jot or tittle of wisdom. But on the whole, the enterprise seems built upon a faulty premise: that a person can “improve” himself by reading books which instruct him concerning the alleged art of “self-actualization.”

It might be interesting to chart the development of this breed of post-modern pop pseudo-philosophy. What was the first of its kind to be published? Perhaps How to Win Friends and Influence People? Or I’m Okay, You’re Okay? Or something with a similarly egregiously eye-rollingly nauseating title?

While many of the authors of these tomes are no doubt sincere (as opposed to being shamelessly parasitic hucksters at heart), still the fact remains that they have taken money from many a credulous and vulnerable soul, casting about desperately for spiritual sustenance. By making these artful pitches to this hapless demographic, these authors have grown quite wealthy at their targeted readership’s collective financial expense.

The desire for self-improvement, to be sure, is great. The need to feel valued and significant is real. The author who spins the best pitch, hits all the right notes, and expertly strikes all of the most pertinent and germane heart-buttons within the chests of his marks…. no doubt has much to gain.

Even if such an author is truly motivated by a desire to help people, he nevertheless ends up exploiting them for his own benefit, whether that was what he meant do, or not.

Self-help, then, amounts to a kind of racket, regardless of whether its practitioners are complicit as racketeers, per se. They take advantage of a conspicuous compulsion on the part of many to improve their lives, to become self-actualized, etc. Perhaps some readers have even managed the feat of legitimate self-transformation through reading this material: it is not for me to say that the books themselves are valueless, insofar as the goals touted within such works are indeed worth striving for.

Instead, I take the view that the entire notion of “self-improvement” is itself a sham.

That is, seen within a wider context, the idea of “self-help” is itself built upon a spurious premise: that the “self” is a thing which ought to be “helped,” that if only “help” were applied, one would find himself snapped back into place, like a properly re-tuned musical instrument, again able to achieve the maximum degree of happiness possible in life.

********************************************************

But… man is not this sort of instrument. Man is a misfit. Man is broken by nature. He is “insistent out of tune.” He consistently wants what is bad for him, and only shuns that which would assist him in becoming his best self. He is prone to “toss yonder like a rind” that which would bring him salvation, and at the same time, to avidly court his own destruction. Man cannot change… unless it be through torment.

Therefore, self-help can only come about through self-harm.

It would be wonderful if we could carefully cultivate our better natures through diligent reflection and concerted effort. Alas, such an outcome cannot follow from such a determination.

True: one can make certain strides. And if one’s goal is worthy, one might actually find oneself growing closer to being the sort of person one wants to be… until it becomes clear that, all the while one has felt himself to be moving forward, his seeming-forward step has in fact been inclining to the left or to the right, and as a result, he has only found himself traversing in a wide and far-flung circle, and his ultimate destination has only proven to be the point where he began this futile journey.

Self-help, to be sure, only accrues through self-harm. A person becomes whole only by suffering, which causes him to become still more broken in his brokenness. He finds his way only by making himself more horribly lost. He assists himself only by hurting himself.

None of this is to say that I recommend doing anything that I will mention in forthcoming dispatches concerning specific methods of self-harm. These missives are not intended as a blueprint to “proper” self-injurious behavior, or an endorsement of any given methods towards this end. Instead, it is a recognition of the necessity of abandoning all hope for self-help as a prerequisite to the task of truly–and enduringly– helping oneself.

Seppuku: The samurai’s ultimate method of self-harm (not endorsed or recommended here)

https://andynowicki.substack.com/p/on-suffering-and-the-sham-of-self