Orwell Watch: On Bill Gates and Climate ‘Denialism’

In the process of writing “Bill Gates Says We’ll Survive Climate Change, World Furious” the other day, I was forced down an interesting rhetorical rabbit hole, but it was too much of a mouthful for that article. The issue however came up again in the new America This Week, as Walter and I discussed Animal Farm. A sign from above! So, returning to the theme:

First, I misused the word “optimism” in describing Gates’s conversion on climate. As the Microsoft co-founder is a monopolistic reptile-whore of the highest order who smells money through his flickering tongue, never budging except in the direction of more profits, my guess is Gates reached a real “tipping point,” in which his climate advocacy had finally become too large of a pimple on the chin of Microsoft’s business model. Amid efforts to lock down the AI-generation equivalent of OS, his old firm will need the energy footprint of a small star. “It turns out humans will survive!” in that sense just feels like a follow up to other cheery posts about next-gen nuke plants.

Nonetheless, Gates and other climate activists have always issued caveats in fine print suggesting warnings like “We have 12 years to live!” weren’t meant to be taken literally, because (as the New York Times just put it) “even the most dire forecasts don’t predict… the end of civilization anytime soon.” As was the case with Covid, tariff catastrophe and other issues, a lot of modern press rhetoric is designed to inspire unmitigated terror. This eliminates phrases like, “Very bad, but…” Things are either total disasters or not.

One fascinating way of doing that has been to reverse the concept of “conspiracy theory.” Once, you were a socially unacceptable kook if you believed in invisible connections between the Bildeburgs, Rothschilds, the CIA, and whatever else you’d read about. You know, like Michael Moore being the Bush administration’s bullhorn:

Ironically, Moore would get a taste of the new conspiracy theory concept when he later produced a movie that questioned the environmentalist movement. He became an exemplar of a new word, one which rendered Gibson-style kookdom upon those who didn’t absolutely believe in things:

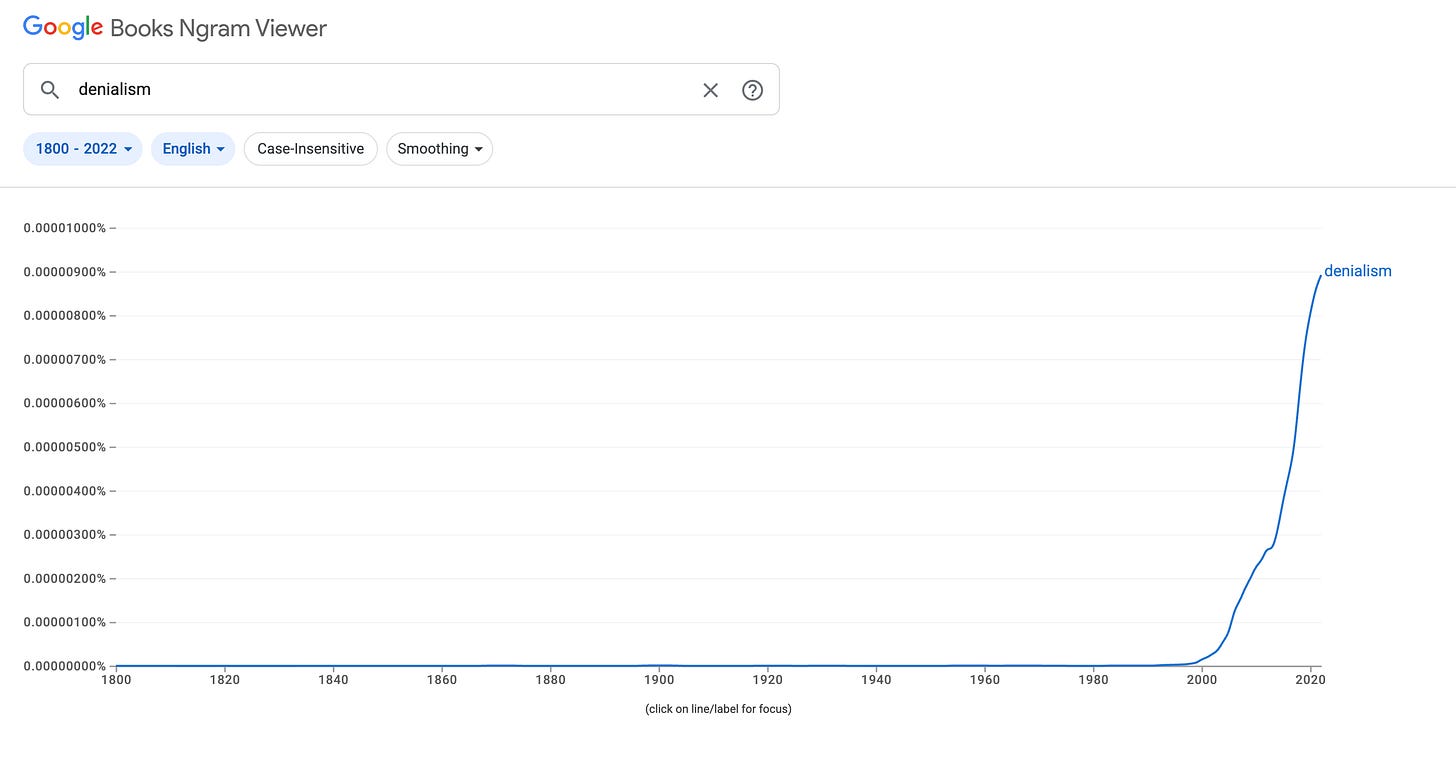

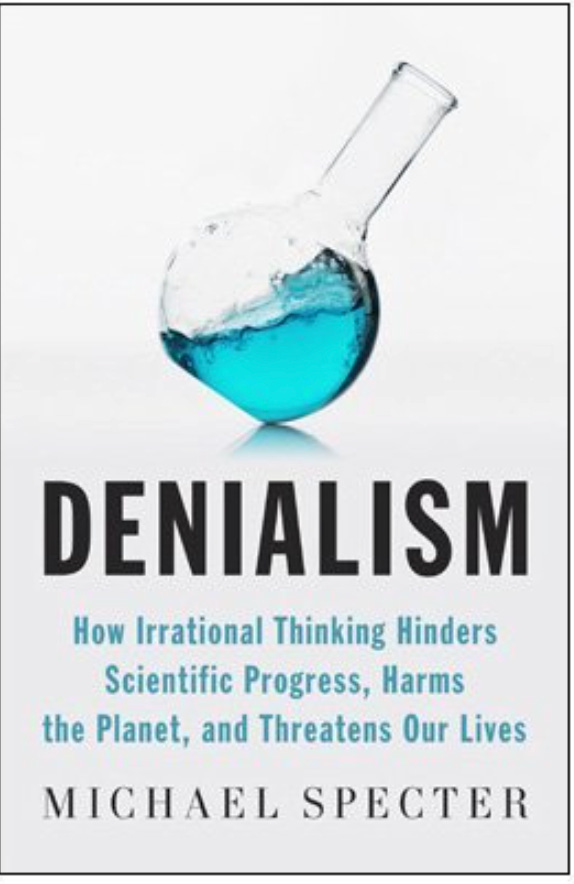

Denialism’s ascent was due almost entirely to the global warming issue. If you look at the graph above you’ll see a spike in the early 2000s, which appears related to a handful of books and articles, mostly about denial of the Holocaust. But the term really took off with the 2009 publication of Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives, by New York Times author Michael Specter:

Future themes not just of media campaigns but efforts to tackle “science denialism” through censorship were present in this book, which Specter explained grew in part out of a dinner party encounter:

Specter, with whom I crossed paths occasionally in Russia, described being invited to dinner by a “prominent, well-read, and worldly woman” who asked what he was working on. He mentioned being “mystified” that so many Americans “seemed to question the fundamental truths of science and their value to society,” examples being “anxiety about agricultural biotechnology, opposition to vaccinations, and the growing power of the alternative health movement.”

The woman “became animated,” saying it was about time somebody “writes the truth about these pharmaceutical companies.” The government, she said, was “no better,” as it’s “destroying our food supply and poisoning our water.” Taken aback, Specter wrote:

The woman didn’t actually say, “It’s all a conspiracy,” but she didn’t have to. Denialism couldn’t exist without the common belief that scientists are linked, often with the government, in an intricate web of lies.

This thesis, that “denialism” is just the flip side of conspiracy theory, is what would soon send the word rocketing into mass use. It’s a perfect twist on Orwell. If the “conspiracy theorist” is the person who too easily accepts an implausible story, the “denialist” is the person who refuses to accept the pronouncements of authority, implicitly because they believe someone else’s crackpot story. Just like that, a skeptic can be repackaged as a conspiracy theorist, even though they’re usually opposites.

Specter’s book went on to posit that scandals like the implosion of Vioxx, a supposed anti-inflammatory wonder drug removed from shelves in the early 2000s over concerns about heart attack and stroke, dealt a death blow to the “cloak of invincibility” citizens previously ascribed to big science and government regulators. But the book featured a fascinating twist.

Because I’ve been living for so long in a world where media insists “the science” is unanimous about climate change, I expected Denialism to argue that the Vioxx mess led straight to people failing to accept scientific pronouncements on the warming planet. I forgot scientists once saw their roles as being gung-ho about fixing problems, not preaching about how we should “recognize our failure,” as UN Secretary General António Guterres put it this week.

Denialism — a book that came out in the first year of Barack Obama’s presidency — turned to the story of Thomas Malthus, the English economist who in 1798 wrote a book arguing that population was already rising at a pace beyond the planet’s ability to feed itself. His error was so historic it garnered a name, the Malthusian Trap. Specter saw the backlash against Big Pharma, government, and genetic engineering as similar flawed thinking, as evidenced by our shopping habits.

“It would be hard to argue with Dostoyevsky’s assertion that a society’s level of civilization can best be judged from its prisons,” he said, but that now, “a supermarket might be a better place to look—and in America today that supermarket would have to be Whole Foods.”

What’s wrong with Whole Foods? To Specter, its “shared fate” slogan, which “would require a sensible effort to keep destructive growth in check, and to find harmony in a world that is rapidly becoming depleted.” Specter thought the belief in “destructive growth” was a Malthusian trap. He wrote about running into a woman in Whole Foods who sounded much like his dinner guest. “What kind of society kills itself by eating?” she said. He concluded:

Calls for sustainability are no longer sales pitches or countercultural affectations; they have become a governing mantra of the progressive mind.

In 2009, it was still possible for a New York Times writer to suggest the world can MacGyver its way out of population problems. Within six years, that would change. The 2008 financial crisis was Vioxx times a billion in its damage to “expertise,” and the election of Donald Trump ended positive pop-culture portrayals of the free market. The old-school Thomas Friedman take on global capitalism — that it was wrapping earth in a “Golden Straitjacket” of irrepressible wealth accumulation — was gone. Soon the only companies that got high marks were those that went out of their way to solve social problems like racism and global warming, like… Whole Foods:

Still, Specter nailed the formula for future propaganda. The real sin was lack of trust in experts, which Specter also identified as coming from fear of “ceding control of our lives to technology,” particularly “highly sophisticated technology we can barely understand.” Denialism, he said, “is at least partly a defense against that sense of helplessness.”

Trumpism was marketed as a similar kind of fear, of ceding control not just to science, but all experts. His election in 2016 was largely explained as a bad case of “truth decay,” with voters losing faith in NATO, the Fed, the mass media, and other institutions. As the Harvard Gazette put it in 2020, “Republicans have successfully seized upon a larger cultural trend of diminished faith in experts around issues like climate change.”

There was probably a lot of truth in the idea that Trump won votes because people lost faith in expertise. The part usually left out is that this distrust was earned. Before the 2008 financial crisis the ultimate “expert,” Alan Greenspan, urged the public to use home equity as ATMs. Ben Bernanke and Timothy Geithner assured us massive intervention to save Wall Street was necessary. The CIA, Pentagon, and Specter’s own New York Times promised us we’d find WMDs in Iraq. Whistleblowers like Ed Snowden and Julian Assange came forward to tell the public it had been lied to a grand scale about whole ranges of things.

By 2016, there was a lot that was rational in rejecting expert pronouncements. This is where Specter’s term, denialism, became a handy way of implying irrationality when there often was none:

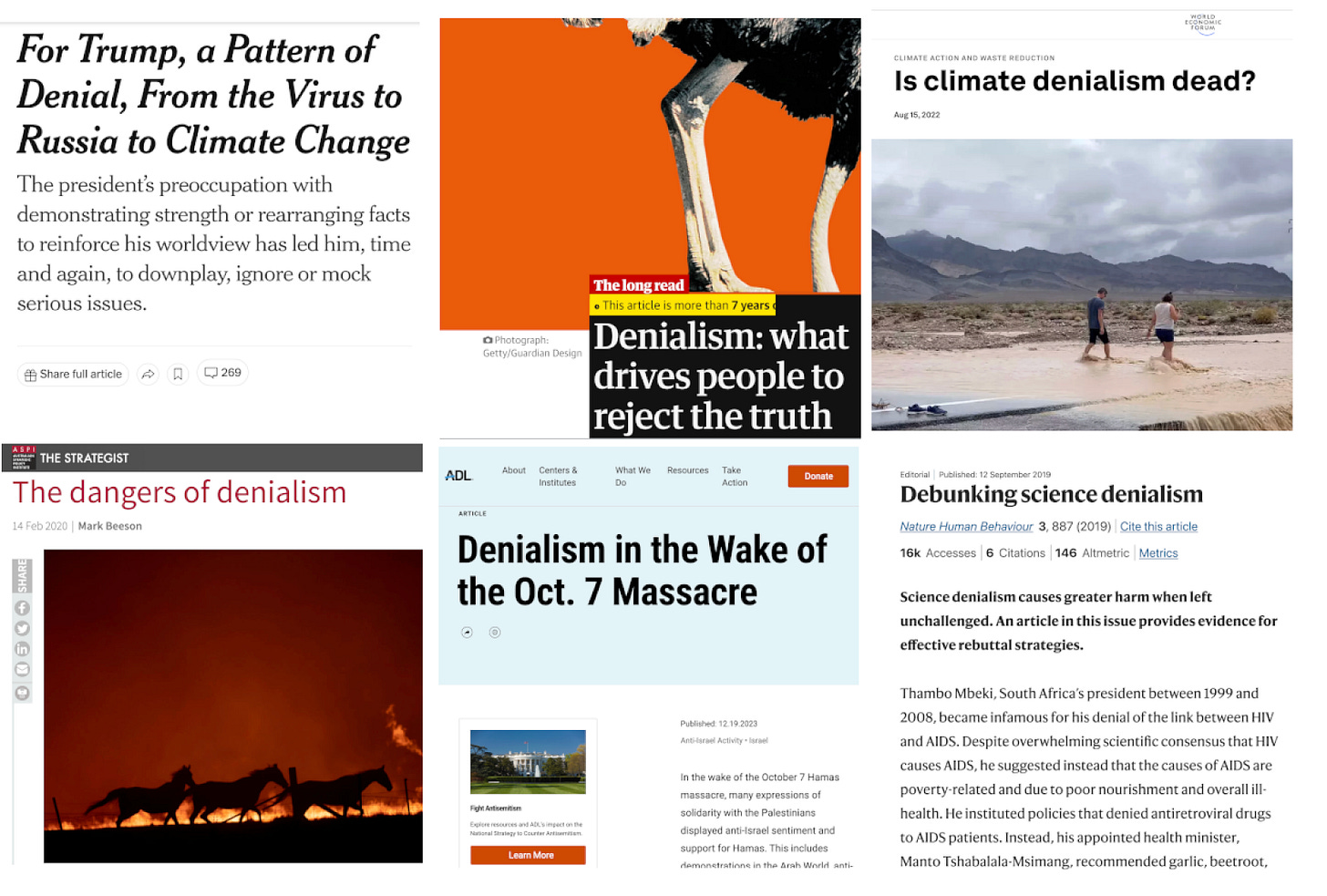

“Denialism” now can refer to anything from refusing to accept Russiagate to denying climate change (the most common use) to denying Covid dictates to election results to the October 7th massacre (or Gaza atrocities). Many of those topics are genuinely controversial, but two in particular — climate change and 2020 “election denial” — have been used over and over to argue against “both-sidesism,” and for “moral clarity” reporting. If there’s only one legitimate “side” to report, then why bother to look for other opinions?

The rise of denialism is a classic case of the tail wagging the dog. The word was rare before because only a handful of things were considered beyond the realm of argument. In the Internet age, however, people were presented with more alternative information than ever before, which meant an explosion of skepticism in part of the population. Another part of the population, however, saw that skepticism as dangerous. Unfortunately, a fair chunk of those people worked in media, where skepticism used to be a job prerequisite. Now they’ve became inquisitors, looking for “denialists” to denounce and expose.

Orwell would have admired the elegance of “denialism.” Unfortunately, he’ll be too busy spinning in his grave for all eternity thanks to the coming remake of Animal Farm-as-capitalist-critique Walter and I just discussed. You can’t have everything!

https://www.racket.news/p/orwell-watch-on-bill-gates-and-climate