Post Attentiveness

Born in 1963, I’m already among the last to remember when flying was civilized, and any half intelligent man was expected to read at least several books a year. Entering college during the Fall of 1982, I wasted no time in using its library, so no later than halfway through my sophomore year, I had read Gide, Gorky, Apollinaire, Cendrars, Stefan Zweig, Whitman, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Roger Shattuck and Robert Henri, on top of Erasmus, Thomas More, Machiavelli, Rabelais, Calderón de la Barca, Conrad, Chekov, Eliot, Beckett, Kate Chopin and Flannery O’Connor, which I had to do for classes. Being so young and stupid, of course I missed much, but serious literature is meant to be reexamined repeatedly. I read other books I no longer remember. I couldn’t penetrate Chaucer and never cared for E. E. Cummings. Even with little life experience, I thought Dickinson embarrassingly dry when not hysterical. Dostoievski, Kafka, Kundera, Borges, Cortazar, Manuel Puig, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Artaud, Jarry, Neruda, Ginsberg, Buchner, Hamsun, Milosz, Simone Weil, Evelyn Waugh, CK Williams and Robert Lowell I’d discover before finally dropping out of college in 1986. Of crazy Artaud, I can recall two lines, “I hate and denounce as cowards all so-called sensate beings.” “And you are quite superfluous, young man!”

Paying $25 rent to live in a dismal house that was more like a shell, I then read 900+ pages of Céline. Just sentences into Death on the Installment Plan, I thought, This is very dangerous, but I forged forward. I’m mapping out my intellectual beginning to show that even a habitually drunk immigrant with an accent and philistine parents could educate himself somewhat if not distracted by constant TV, nonstop music or, of course, the cellphone. I bought my first computer in 1995.

Had I been born in, say, 1985, I would most likely be a slobbering retard who can’t wait to vote again and again, “to make a difference.” Of course, I’d comment diarrheically online behind an original pseudonym appended with PhD. Even as my house, mama and society go up in flames, it’s important I keep the lowest profile, fly miles under the radar and never dox myself. Above all, I mustn’t hate a systematic, steady hatred nakedly applied against meaning itself. To even hint at it would be anti-schematic. Please don’t report me, sir! If unusually brave, I might risk waving a hand scrawled sign at mostly indifferent traffic for half an hour every five years, among masked comrades.

In any new city, one must find great bookstores. Before the internet, this meant actually walking around. Bookish locals could also help you out, but they were very rare. In Philadelphia, South Street Books was pretty good, but Factotum, also on South but on the wrong side of Broad, was even better. Browsing books on shelves leads to discoveries. The internet killed this practice. Finding books by key words keeps you in the tiniest ghettos.

A college professor, Stephen Berg, was the editor of the American Poetry Review. Among English language poetry zines, it had the highest circulation at over 20,000. Published six times a year, it also appeared more frequently than all. Most were quarterlies. At Steve’s office and house, books were all over. Of course, as a powerful editor, he had thousands sent to him unsolicited. Though we became drinking buddies, Steve got angry at me for two reasons. Already knowing I didn’t respect his poetry, Steve ditched our friendship when I didn’t immediately intercede on his behalf at Seven Stories Press. Emailing Steve from Italy, I said I would talk to Dan Simon in person, but that wasn’t enough. At some Manhattan bar, Dan said he didn’t need anyone to tell him what to think. Nothing I said could change his mind about Steve’s manuscript.

All writers think they’re underappreciated, overlooked or slandered. With fewer readers paying attention, this bitterness has only increased tragically, or perhaps just pathetically.

Typing this at Cà Phê Cà Pháo, I have in front me a 2024 edition of Ngô Sĩ Liên’s history of Vietnam, first published in 1479. I’m the only one who has shown any interest in this 1,284 page volume. Though the café’s owner has only bought it as a decoration, Ngô Sĩ Liên shouldn’t complain. Five centuries after his death, he’s still visible, if only from the side and afar, to dozens of distracted zombies daily, when they’re not admiring their own selfies or playing video games. At least he wasn’t castrated like Sima Qian. Uppity, name dropping intellectuals deserve no less.

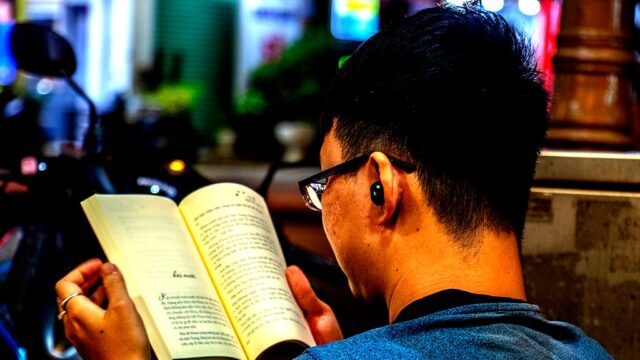

Living in Vung Tau four years, I’ve only seen three people with books. One had volumes by some new agey guru. Another was reading short stories by Nam Cao, so that was encouraging. Last night at Cóc Cóc, there was a guy reading a book. Before I got too excited, I noticed his earbud. To read with music is nearly as bad as reading on the toilet. His author was the super lame Nguyễn Nhật Ánh.

Twenty-first century man has stopped reading everything, not just books. It’s a question of focus. Neurologically damaged, he can’t read a face, the sky, his room, city or nation. Skimming or flitting while taking a shit or masturbating with the worst music on full blast is not reading.

Just yesterday, one “john henninger” emailed me, “You had preferred kamala for a week before teeing off on her!” No salution, introduction, context or, clearly, any real reading, since I’ve never said anything positive about Kamala Harris. What prompted this idiocy was the first 142 words of a 901-word article. I canceled his free subscription. There are people who subscribe to hundreds of SubStacks, just so they can leap into a few to fart and run. It’s an epidemic.

We’ve sunk a long way. In his The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussell points out:

The American Civil War was the first, Theodor Ropp observes, “in which really large numbers of literate men fought as common soldiers.” By 1914, it was possible for soldiers to be not merely literate but vigorously literary, for the Great War occurred at a special historical moment when two “liberal” forces were powerfully coinciding in England. On the one hand, the belief in the educative powers of classical and English literature was still extremely strong. On the other, the appeal of popular education and “self-improvement” was at its peak, and such education was still conceived largely in humanistic terms.

Again, it’s not just knowledge you gain from reading, but how to be attentive. Without attentiveness, which doesn’t have to come from reading, of course, there’s no respect or love for anything, only the most narrow, hateful and desperate form of self love. Sunk in it, you’re literally in hell.