Right at the Wrong Time

Enoch Powell, mass immigration, and the speech that Britain was not prepared to hear.

“As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood.’” — Enoch Powell

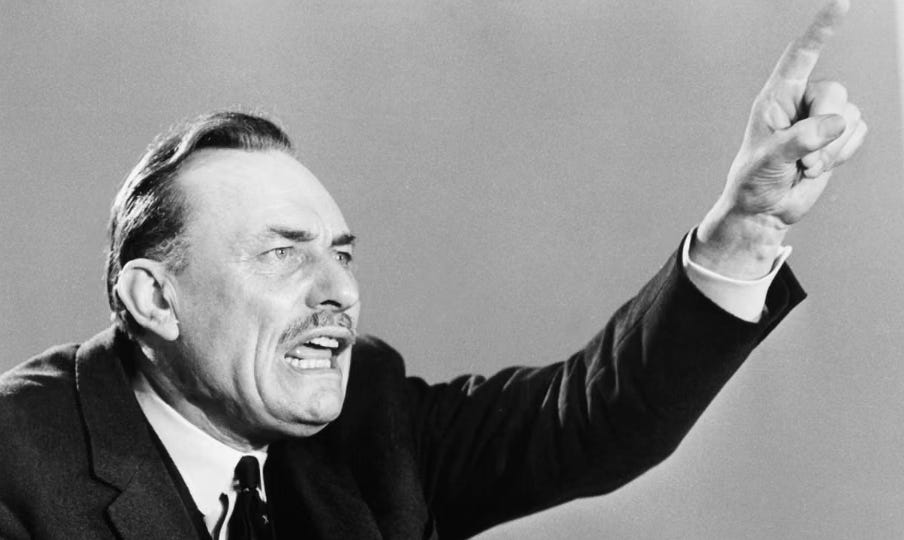

On 20 April 1968 Sir Enoch Powell, then a rising star in the Conservative Party, stunned Britain with a speech in Birmingham that seemed to portend catastrophe. A classical scholar by training and decorated WWII officer, Powell warned that uncontrolled immigration would fracture the nation. He invoked Virgil, “as I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood’”.1 In the charged atmosphere of the late-1960s, as race riots shook American cities and Britain debated new immigration and race laws, Powell’s apocalyptic imagery was electric. The very next day Prime Minister-in-waiting Edward Heath sacked him as Shadow Defence Secretary. Heath told reporters that Powell’s Birmingham address was “racialist in tone” and “unacceptable…from one of the leaders of the Conservative Party”.2 By the end of that week every senior Tory on the front bench had demanded his removal, sealing Powell’s expulsion.3

Powell’s ejection was swift, but his speech also found an avid audience. Inside Whitehall and Fleet Street commentators roundly condemned him, but outside Downing Street opinion polls showed he had tapped a nerve. Within days a BBC-commissioned survey found roughly three-quarters of Britons agreed with Powell’s core worry, that mass black immigration would likely lead to violence.4 Indeed, hundreds of London dockers marched under banners proclaiming “Enoch Was Right”.5 Even Conservative dissidents noted that Powell had become “Mr National Opinion” a mouthpiece for widespread private anxieties.6 In Parliament and the press the tone was one of horror and relief; in the pubs and factories of the Midlands and North, a whisper ran: here was a politician finally giving voice to fears many felt but dared not say. This paradox, pariah in power, prophet among the people, framed the tragic arc of Powell’s career. Viewed by his party as a toxic liability, he was by some voters lionised as a truth-teller.

Scholar, Soldier, Statesman

Powell’s biographers emphasise that he was far more than a demagogue. Born in 1912 to a schoolmaster father, he won a scholarship to King Edward’s School in Birmingham where he excelled in Latin and Greek. He went on to Trinity College, Cambridge, and emerged with a “double-starred First” in Classics, an exceptionally rare distinction.7 He then became a Cambridge fellow and, at age 25, Professor of Greek at Sydney University.89 By 1939 he was back in Britain, voluntarily enlisting as a private in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. Powell rose swiftly: by age 30 he was a lieutenant-colonel in intelligence, and was honoured with an MBE for his service. After the war he entered Parliament (as a Tory MP in 1950), and served as Minister of Health (1960–63) and then Shadow Defence Secretary. He wrote books on classical and political subjects, and even poetry.10 Everyone who worked with him noted his prodigious intellect, Macleod quipped Powell had been “driven mad by the remorselessness of his own logic” and his aristocratic manner.11

But Powell was also a high Tory nationalist: he saw Britain’s global decline as a personal affront. The loss of India (where Powell served in the 1940s) became central to his worldview. He later confessed that the Partition horrors convinced him “communalism and democracy… are incompatible”, and that Western society would descend into ethnic and religious faction if its coherence were undermined.12 In parliament he argued against decolonisation and preached the virtues of Empire as late as the 1950s. Yet by the 1960s he had embraced a more parochial patriotism: he urged the Tory Party to “cure” itself of its attachment to the Commonwealth and instead “find its patriotism in England”.13 Powell’s patriotism was suffused with a romantic vision of England “at the heart of a vanished Empire, amid the fragments of demolished glory” that he insisted must be preserved.14 In this sense he was both a classical intellectual and an old-school Burkean populist: a “visionary seer” willing to embrace extremes in his fear of national decline.

The Migrant Challenge in the 1960s

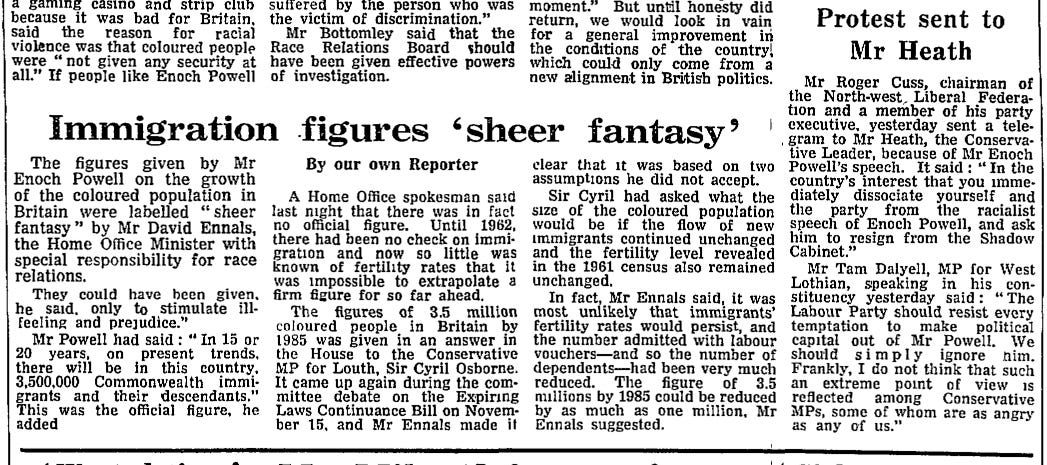

Powell spoke in the midst of a demographic upheaval. The 1948 British Nationality Act had made some 800 million colonial subjects British citizens with a right to live in the UK. The results became dramatic by the 1960s: millions migrated from the Caribbean, South Asia, Africa and elsewhere. By 1961 Commonwealth immigration had skyrocketed, from roughly 3,000 per year in 1953 to about 136,000 in 1961.15 London, Birmingham, Bradford and other industrial cities saw entire neighbourhoods change nationality within a few years. Public reaction was mixed but often tense. In Parliament itself, Home Secretary Rab Butler alarmed colleagues in 1961 when he noted that a quarter of the world’s population (then legally entitled to emigrate) might settle in Britain.16 Within months the Conservative government passed the first Commonwealth Immigrants Act (1962), requiring incoming migrants to have jobs or skills. For Powell and many Conservatives this was merely the start of common-sense reform. By 1965 public unease and activists’ reports of racial bias in housing prompted the first Race Relations Act, banning discrimination in public accommodations.17 Labour’s 1968 Race Relations Act went further, outlawing racial bias in jobs and housing just as Powell delivered his speech.

In short, Powell spoke to a nation already girdling itself for change. By the mid-1960s there were nearly a million immigrants in Britain, and more arriving every year. Historians note that “almost everybody” then agreed the Commonwealth migration rate was too steep for Britain easily to absorb”.18 The Conservative Party itself under Edward Heath openly debated repatriation schemes. The June 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act (ironically passed just weeks before Powell’s speech) tightened visas for East African Asians holding British passports. In this charged climate, with race legislation on the statute books and immigration still high, Powell threw metaphorical gasoline on the fire.

Nationhood and Demographic Change in Powell’s Thought

Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech mixed classical allusion with social critique. He decried Britain’s “total transformation to which there is no parallel in a thousand years of English history”. His core demand was drastic population control: “the total inflow for settlement should be reduced at once to negligible proportions”. Allowing “some fifty thousand” dependents in each year was, he said, “literally mad” for Britain. Powell proposed even incentivising voluntary re-emigration, one newspaper reported he urged “generous grants and assistance” for immigrants who chose to return home.19 In his analysis, every social problem was blamed on unchecked demographic change. Powell argued that while “many thousands” of immigrants wanted to integrate, a majority did not; and more, he insinuated some immigrant leaders sought “actual domination” of others.20

To justify these claims, Powell appealed to an aggrieved “national opinion.” He illuminated white Britons as victims of elite decisions. Saying they had not been “consulted” on mass migration (which they hadn’t), he described how they found themselves “strangers in their own country”. He complained of a new “one-way privilege” under law, that immigrants would gain protections denied to natives. All this was meant to explain angry white resentment. Powell explicitly accused the metropolitan elite of deceit: he compared today’s pro–race-relations journalists to those who in the 1930s “tried to blind this country to the rising peril” of fascism.21 By casting himself as a lone truth-teller shouting against politically correct orthodoxy, Powell framed his argument as one that London and Westminster would not allow.

In sum, Powell argued that preserving the “unimaginable affinities” of the English nation required halting immigration. He set forth a prophetic vision: migrants failing to learn English would balkanise society, birthrates would overwhelm natives, and streets would run red with a conflict “on the other side of the Atlantic” meaning America’s race riots, that he said would soon come to Britain. His apocalyptic language (“funeral pyre”, “match onto gunpowder”) underscored a civilisational argument: unless an “urgent action” were taken, he warned, Britons risked an intractable ethnic war.22

The Aftermath and Historical Reality

The immediate impact was dramatic. Premier Edward Heath and his front bench drew the line sharply: Powell was expelled and the Conservative leadership closed ranks.23 The press was unanimous in condemnation: The Times called the speech “racialist” and “an evil speech”. But wider public opinion told another story. Opinion polls after the speech showed roughly 70–75% of Britons agreeing with Powell’s core point that black immigration could lead to unrest.24 Historian Ferdinand Mount notes that after 1968 “polls showed… 74 per cent of the public approved” of Powell’s speech, and Powell received 100,000 letters of support, almost all praising him.25 Even moderate leaders found their constituents siding with Powell. A young Michael Heseltine (then a Tory MP) conceded that in his rural constituency “the people” felt Powell “was right” even though none had met a single immigrant. In the 1970 election, Heath himself won in part by carrying working-class Powell sympathisers, “heard muttering ‘Enoch was right’ behind closed doors”.26

On the streets, the fallout was mixed. In Birmingham itself, where the speech was given there was little immediate disorder. According to one eyewitness, only “one person voiced annoyance” during the meeting.27 But outside the industrial Midlands, Powell had become a potent symbol. Hundreds of dockworkers in London marched, placards raised, in his defense[5]. The Communist Party and anti-racist organisations mobilised counter-demonstrations. In the balance, Powell’s speech arguably shifted the Overton window: it proved inescapable that immigration would be a wedge issue. Some historians argue Powell’s activism helped bring immigration into everyday politics, his warnings would haunt British discourse for decades.

Some of Powell’s predictions played out. Powell knew that population change could reshape Britain for the worst; in this he was largely vindicated. By 2000 he had estimated five to seven million Commonwealth immigrants and descendants (about 10% of Britain.28 The 2011 census recorded roughly that magnitude (4.4 million Asian British, 1.9 million Black British, 1.25 million mixed race, around 10% of 63 million). Today one can find second- and third-generation immigrants in top jobs, government and even the monarchy. In this sense Powell’s arithmetic was prophetic.

Other developments undermined Powell’s framework. He fully anticipated the rise of identity politics and the empowered grievance industry. Indeed, the Race Relations Acts themselves created exactly what he feared: a new bureaucratic “morality police” empowering minority groups. City Journal editor Dominic Green argues that the legislation Powell despised eventually produced an unelected class of left-leaning civil servants and lawyers incentivising ethnic “communitarianism”, in effect Balkanising Britain into competing identity blocs. In that sense, Powell was right to foresee growing politicisation of race (indeed, he predicted the white majority would feel alienated).

Cassandra and the Closed Doors of Power

Powell’s place in history is often framed in classical terms: he became a Cassandra. Cassandras in myth were cursed to utter true prophecies that no one would heed. Powell certainly fit that image. Even sympathetic commentators noted that many of his “troubling predictions” about Britain’s decline and the fragility of the United Kingdom, eventually came to pass, even as Powell himself was shut out of power. In 2020 one historian described him as “viewed in his lifetime as…a Cassandra-like doomsayer” whose vision has been borne out by events.29

“There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”

– Victor Hugo, Histoire d’un crime (1852)