The AI Bubble and the U.S. Economy: How Long Will the ‘Hallucinations’ Last?

Yves here . This is a devastating, indispensable article by Servaas Storm on how AI fails to live up to its repeatedly hyped performance promises, and never will, no matter how much money and computing power is poured into it. Yet AI, which Storm calls “Artificial Information,” continues to receive ratings worse than during the dotcom craze, even as the errors only increase.

By Servaas Storm, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Delft University of Technology. Originally published on the website of the Institute for New Economic Thinking.

This article argues that (i) we have reached ‘peak GenAI’ for current Large Language Models (LLMs); scaling up (building more data centers and deploying more chips) will only get us so far toward the goal of ‘Artificial General Intelligence’ (AGI); the returns are rapidly diminishing; (ii) the AI LLM industry and the broader US economy are in a speculative bubble that is about to burst.

The US is experiencing an extraordinary, AI-driven economic boom: the stock market is soaring thanks to the exceptionally high valuations of AI-related technology companies, which are fueling economic growth by spending hundreds of billions of dollars on data centers and other AI infrastructure. The AI investment boom is based on the belief that AI will make workers and companies significantly more productive, which in turn will boost corporate profits to unprecedented heights. But the summer of 2025 brought no good news for generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) enthusiasts, all of whom had been energized by the inflated promises of people like OpenAI’s Sam Altman that “artificial general intelligence” (AGI), the holy grail of current AI research, was within reach.

Let’s take a closer look at the hype. As early as January 2025, Altman wrote that “we are now confident we know how to build AGI.” Altman’s optimism echoed claims by OpenAI’s partner and main financial backer, Microsoft, which published a paper in 2023 claiming that the GPT-4 model already showed “sparks of AGI.” Elon Musk (in 2024) was similarly convinced that the Grok model, developed by his company xAI, would achieve AGI, an intelligence “smarter than the smartest human,” likely by 2025 or 2026 at the latest. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg said his company was committed to “building full general intelligence” and that superintelligence is now “in sight. ” Similarly, Dario Amodei , co-founder and CEO of Anthropic, said that “powerful AI,” i.e., smarter than any Nobel laureate in any field, could come as early as 2026, ushering in a new era of health and abundance — the US would become a “nation of geniuses in a data center,” if… AI weren’t killing us all.

For Musk and his fellow GenAI travelers, the biggest obstacle to AGI is the lack of computing power (installed in data centers) to train AI bots, which in turn is due to a lack of sufficiently advanced computer chips. Morgan Stanley estimates that the demand for more data and increased data processing capacity will require approximately $3 trillion in capital by 2028. This would exceed the capacity of the global credit and derivatives markets . Spurred by the need to win the AI race with China, GenAI propagandists are convinced that the US can be put on the yellow brick road to the Emerald City of AGI by building more data centers faster (an undeniably “accelerationist” term).

Interestingly, AGI is a poorly defined concept, and perhaps more of a marketing concept used by AI promoters to convince their funders to invest in their efforts. Essentially, it means that an AGI model can go beyond the specific examples in its training data, similar to how some humans can do almost any kind of work after seeing a few examples of how to perform a task, learning from experience and adapting methods as needed. AGI bots will be able to outsmart humans, generate new scientific ideas, and perform both innovative and routine coding. AI bots will tell us how to develop new drugs to cure cancer, combat global warming, drive our cars, and grow our genetically modified crops. In a radical creative destruction, AGI would thus transform not only the economy and the workplace, but also the systems of healthcare, energy, agriculture, communications, entertainment, transportation, research and development, innovation, and science.

OpenAI’s Altman boasted that AGI can “discover new science” because “I think we’ve cracked the reasoning in the models,” adding that “we still have a long way to go.” He “thinks we know what to do,” saying that OpenAI’s o3 model “is already pretty smart” and that he’s heard people say, “Wow, this is like a good PhD.” Announcing the launch of ChatGPT-5 in August, Altman posted a message online: “We think you’ll like GPT-5 much more than previous AIs. It’s useful, smart, fast, and intuitive. With GPT-5, it’s now like talking to an expert—a true PhD-level expert in whatever field you need, who can help you with all your goals.”

But then things started to go downhill fast.

ChatGPT-5 is a disappointment

The first bad news is that the much-touted ChatGPT-5 has proven to be a flop— incremental improvements wrapped in a routing architecture , far from the breakthrough to AGI that Sam Altman had promised. Users are disappointed. As the MIT Technology Review reports , “The much-touted release makes several improvements to ChatGPT’s user experience. But it’s still a long way from AGI.” Worryingly, OpenAI’s internal tests show that GPT-5 “hallucinates” about one in ten responses to certain real-world tasks when connected to the internet. Without internet access, however, GPT-5 is incorrect in nearly one in two responses , which is concerning. Even more worrying, “hallucinations” can also reflect biases hidden within datasets. For example, an LLM might “hallucinate” about crime statistics reflecting racial or political biases simply because it has learned from biased data.

What’s striking here is that AI chatbots can be actively used to spread misinformation (see here and here ). According to recent research, chatbots spread false claims 35% of the time when asked about controversial news topics—nearly double the 18% figure a year ago ( here ). AI selects, organizes, presents, and censors information, influences interpretations and debates, and promotes dominant (mainstream or preferred) positions while suppressing alternatives, quietly removing inconvenient facts, or fabricating convenient facts. The key question is: who controls the algorithms? Who sets the rules for the tech brethren? Clearly, by making it easy to spread “realistic-looking” disinformation and biases, and/or suppress critical evidence or argumentation, GenAI has and will continue to impose significant societal costs and risks—which must be factored into any assessment of its impact.

Building bigger LLMs leads nowhere

The ChatGPT-5 episode raises serious doubts and existential questions about whether the GenAI industry’s core strategy of building ever-larger models based on ever-larger data distributions has already hit a wall. Critics, including cognitive scientist Gary Marcus ( here and here ), have long argued that simply scaling up LLMs won’t lead to AGI, and GPT-5’s disappointing stumbling blocks confirm that concern. It’s increasingly accepted that LLMs aren’t based on sound and robust world models , but are built to complete automatically based on sophisticated pattern recognition. That’s why, for example, they still can’t even play chess reliably and continue to make perplexing errors with astonishing regularity.

My new INET Working Paper discusses three sobering studies that show that new, ever-larger GenAI models don’t get better, but worse, and don’t reason, but rather parrot argument-like text. To illustrate, a recent paper by scientists from MIT and Harvard shows that even when trained on all physics, LLMs fail to even discover the existing general and universal physical principles underlying their training data. Vafa et al. (2025) show that LLMs following a “Kepler-like” approach can successfully predict a planet’s next orbital position, but fail to find the underlying explanation for Newton’s law (see here ). Instead, they resort to invented rules that successfully predict the planet’s next orbital position, but these models fail to find the force vector underlying Newton’s insight. The MIT-Harvard paper is explained in this video . LLMs cannot and will not derive the laws of physics from their training data. Remarkably, they cannot even identify the relevant information on the internet. Instead, they invent it.

Worse still, AI bots are incentivized to make guesses (and give an incorrect answer) rather than admitting they don’t know something . This problem is recognized by researchers at OpenAI in a recent paper . Guessing is rewarded—because who knows, it might be right. The error is currently uncorrectable. Therefore, it might be wise to think of “Artificial Information” rather than “Artificial Intelligence” when using the abbreviation AI. The conclusion is clear: this is very bad news for anyone hoping that further scaling—building ever-larger LLMs—would lead to better results (see also Che 2025 ).

95% of generative AI pilot projects in companies fail

Companies had been rushing to announce AI investments or tout AI capabilities for their products, hoping to boost their stock prices. Then came the news that the AI tools weren’t doing what they were supposed to, and people were realizing it (see Ed Zitron ). An August 2025 report , “The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025,” published by MIT’s NANDA Initiative , concluded that 95% of generative AI pilot projects in enterprises failed to increase revenue growth. As Fortune reported , “generic tools like ChatGPT […] stagnate in enterprise use because they don’t learn from or adapt to workflows.” Indeed.

Companies are indeed taking a step back after cutting hundreds of jobs and replacing them with AI. For example, the Swedish “Buy Burritos Now, Pay Later” company Klarna boasted in March 2024 that its AI assistant was doing the work of 700 (laid-off) employees, only to rehire them (unfortunately as gig workers) in the summer of 2025 (see here ). Other examples include IBM, which was forced to rehire staff after laying off some 8,000 employees to implement automation ( here ). Recent data from the US Census Bureau by company size shows that AI adoption is declining among companies with more than 250 employees.

MIT economist Daren Acemoglu (2025) predicts a fairly modest productivity effect from AI over the next 10 years and warns that some AI applications could have negative societal value. “We’re still going to have journalists, we’re still going to have financial analysts, we’re still going to have HR people,” Acemoglu says . “It’s going to impact a number of white-collar jobs that have to do with data summarization, visual matching, pattern recognition, and so on, and those are essentially about 5% of the economy.” Similarly, in a recent NBER Working Paper, Anders Humlum and Emilie Vestergaard (2025) use two large-scale surveys on AI adoption (end of 2023 and 2024) across 11 exposed occupations (25,000 workers in 7,000 workplaces) in Denmark to show that the economic impact of GenAI adoption has been minimal: “AI chatbots have had no significant impact on income or recorded hours in any occupation, with confidence intervals excluding effects exceeding 1%. Modest productivity gains (average time savings of 3%), combined with weak wage pass-through, help explain these limited labor market effects.” These findings provide a much-needed reality check for the hyperbole that GenAI will take over all our jobs. The reality is still a long way off.

GenAI won’t even make techies obsolete, contrary to what AI enthusiasts predict. OpenAI researchers found (in early 2025) that advanced AI models (including GPT-4o and Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet) are still no match for human programmers. The AI bots failed to understand the prevalence of bugs or their context, leading to incorrect or insufficient fixes. Another new study from the nonprofit Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR) concludes that programmers using AI tools in early 2025 will actually be slower when using AI tools. They will spend 19 percent more time using GenAI than when actively coding themselves (see here ). Programmers spent their time checking AI output, driving AI systems, and correcting AI-generated code.

The US economy as a whole is hallucinating

The disappointing introduction of ChatGPT-5 raises doubts about OpenAI’s ability to build and market consumer products that users are willing to pay for . But the point I’m making isn’t just about OpenAI: the US AI industry as a whole is built on the premise that AGI is just around the corner. All that’s needed is sufficient “computing power” —meaning millions of Nvidia AI GPUs, enough data centers, and enough cheap electricity—to perform the massive statistical pattern mapping required to generate (a semblance of) “intelligence.” This, in turn, means that “scaling” (investing billions of dollars in chips and data centers) is the only way forward—and this is precisely what tech companies, Silicon Valley venture capitalists, and Wall Street financiers are good at: mobilizing and spending funds, this time on “scaling” generative AI and building data centers to meet all the expected future demand for AI usage.

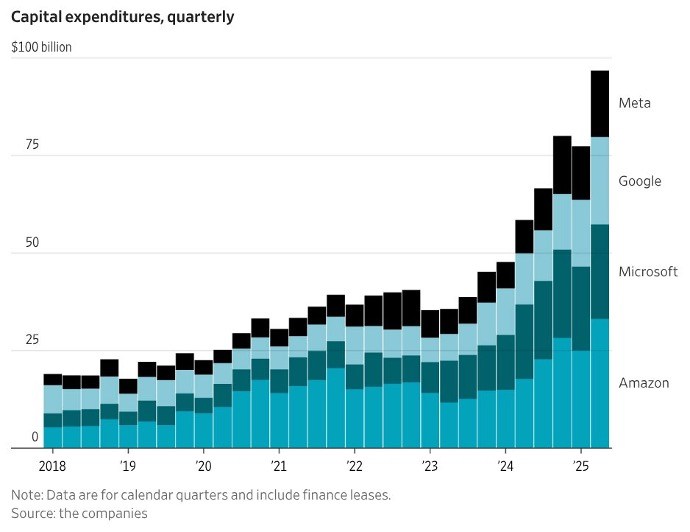

In 2024 and 2025, major tech companies invested a staggering $750 billion in data centers, and they plan to invest a total of $3 trillion in data centers between 2026 and 2029 ( Thornhill 2025 ). The so-called “Magnificent 7” (Alphabet, Apple, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla) spent more than $100 billion on data centers in the second quarter of 2025; Figure 1 shows the capital expenditures for four of the seven companies.

FIGURE 1

Christopher Mims (2025), https://x.com/mims/status/1951…

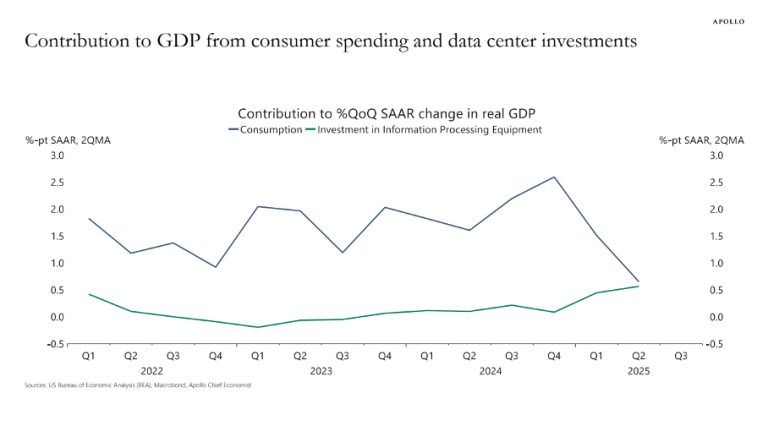

The surge in corporate investment in “information processing equipment” is enormous. According to Torsten Sløk, chief economist at Apollo Global Management, the contribution of data center investment to (slow) US real GDP growth in the first half of 2025 will have equaled that of consumer spending ( Figure 2 ). Financial investor Paul Kedrosky notes that capital expenditures for AI data centers (in 2025) will have surpassed the peak of telecom spending during the dotcom bubble (1995-2000).

FIGURE 2

Source : Torsten Sløk (2025). https://www.apolloacademy.com/…

In the wake of the AI hype and hyperbole, tech stocks have soared in value. The S&P 500 index rose by approximately 58% between 2023 and 2024, primarily due to the rise in share prices of the Magnificent Seven. The weighted average share price of these seven companies rose by 156% between 2023 and 2024, while the other 493 companies saw an average share price increase of only 25%. The US stock market is largely driven by AI.

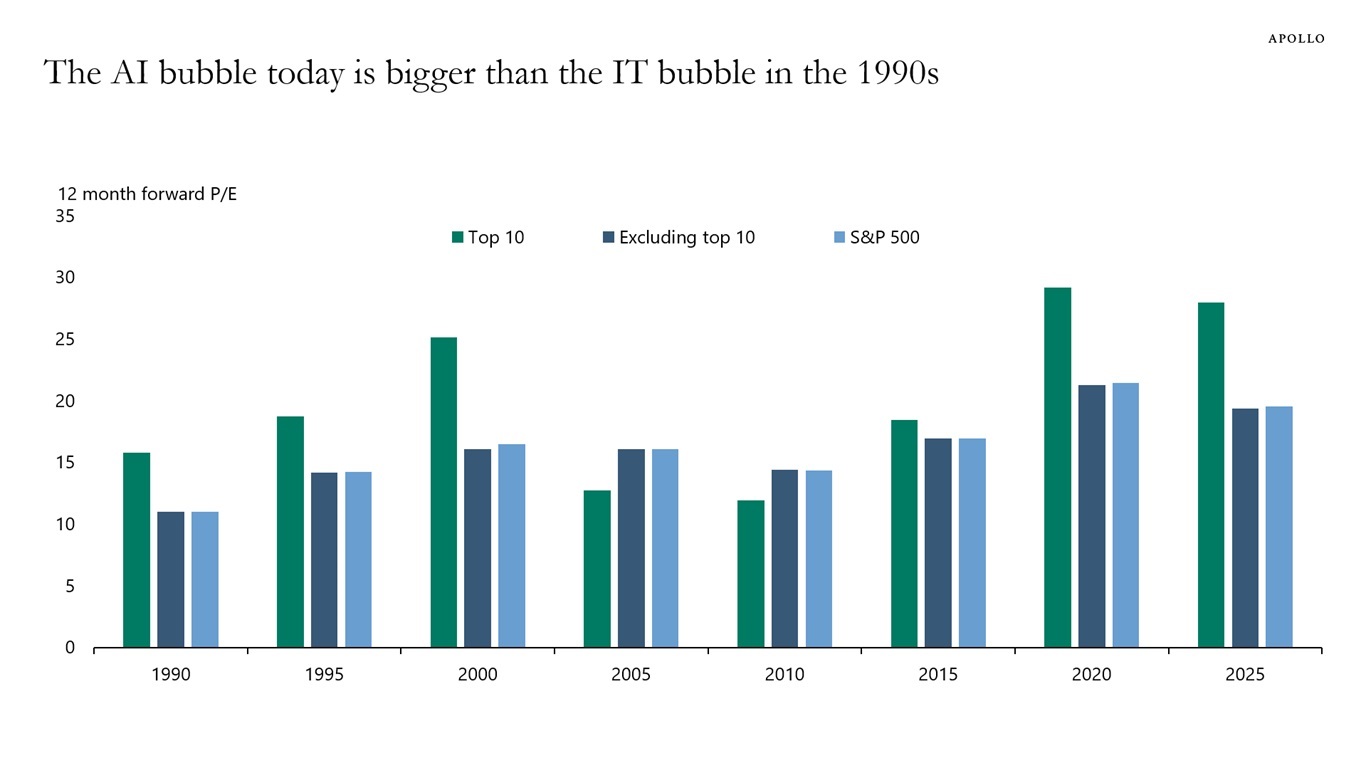

Nvidia’s stock has surged over 280% over the past two years amid explosive demand for its GPUs from AI companies. As one of the most prominent beneficiaries of the insatiable demand for GenAI, Nvidia now boasts a market capitalization of over $4 trillion, the highest valuation ever for a publicly traded company. Does this valuation make sense? Nvidia’s price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio peaked at 234 in July 2023 and has since fallen to 47.6 in September 2025 — still very high by historical standards (see Figure 3 ). Nvidia sells its GPUs to neocloud companies (such as CoreWeave, Lambda, and Nebius), which are financed with loans from Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Blackstone, and other Wall Street private equity firms, backed by GPU-filled data centers. In key cases, as explained by Ed Zitron , Nvidia offered the loss-making neocloud companies the opportunity to buy billions of dollars worth of unsold cloud computing assets, effectively backing its customers – all in the expectation of an AI revolution yet to come.

Similarly, Oracle Corp. (not included in the “Magnificent 7”) saw its share price rise by more than 130% between mid-May and early September 2025 after announcing its $300 billion cloud computing infrastructure deal with OpenAI. Oracle’s price-to-earnings ratio soared to nearly 68, meaning financial investors are willing to pay nearly $68 for $1 of Oracle’s future earnings. A clear problem with this deal is that OpenAI doesn’t have $300 billion; the company suffered losses of $15 billion between 2023 and 2025 and is expected to incur another $28 billion in cumulative losses between 2026 and 2028 (see below). It’s unclear and uncertain where OpenAI will get its money. Ominously, Oracle will have to build OpenAI’s infrastructure before it can generate any revenue. If OpenAI can’t afford the massive computing capacity it bought from Oracle, which seems likely, Oracle will be left with the expensive AI infrastructure for which it may not be able to find alternative customers, especially once the AI bubble bursts.

So, tech stocks are significantly overvalued. Torsten Sløk, chief economist at Apollo Global Management, warned (in July 2025) that AI stocks are even more overvalued than dot-com stocks were in 1999. In a blog post, he illustrates how the price-to-earnings ratios of Nvidia, Microsoft, and eight other tech companies are higher than they were during the dot-com era (see Figure 3 ). We all remember how the dot-com bubble ended — and so Sløk is right to sound the alarm about the apparent market frenzy, fueled by the “Magnificent 7,” all of whom have invested heavily in the AI industry.

Big Tech doesn’t buy or operate these data centers themselves; instead, construction companies build them and then buy them up by data center operators, who lease them to (for example) OpenAI, Meta, or Amazon (see here ). Wall Street private equity firms like Blackstone and KKR are investing billions of dollars to acquire these data center operators, using commercial mortgage-backed securities as a financing source . Data center real estate is a hot new asset class that’s starting to dominate financial portfolios. Blackstone calls data centers one of its “most compelling investments.” Wall Street loves data center leases, which offer long-term, stable, and predictable revenues paid for by AAA-rated customers like AWS, Microsoft, and Google. Some Cassandras warn of a potential data center oversupply, but given that “the future will be based on GenAI,” what could possibly go wrong?

FIGURE 3

Source : Torsten Sløk (2025), https://www.apolloacademy.com/…

In a rare moment of candor, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman was right. “Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overly excited about AI?” Altman said during a dinner interview with reporters in San Francisco in August. “My opinion is yes.” He also compared the current AI investment frenzy to the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. “I think someone is going to get burned,” Altman said. “Someone is going to lose a phenomenal amount of money—we don’t know who…” but (judging by what has happened in previous bubbles) it most likely won’t be Altman himself.

The question, then, is how long investors will continue to support the sky-high valuations of the leading companies in the GenAI race. The AI industry’s revenues remain dwarfed by the tens of billions of dollars spent on data center growth. According to an optimistic S&P Global research report published in June, the GenAI market is expected to generate $85 billion in revenue by 2029. However, Alphabet, Google, Amazon, and Meta are expected to collectively spend nearly $400 billion on capital expenditures in 2025 alone. At the same time, the AI industry’s combined revenue is barely higher than that of the smartwatch industry ( Zitron 2025 ).

What if GenAI simply isn’t profitable? This question is relevant given the rapidly diminishing returns on the exorbitant capital expenditures for GenAI and data centers, and the disappointing user experience of 95% of companies that have implemented AI. One of the world’s largest hedge funds, Florida-based Elliott , told clients that AI is overvalued and that Nvidia is in a bubble, adding that many AI products “will never be cost-effective, will never work properly, will consume too much energy, or will prove unreliable.” “There are few real-world applications,” the company stated, other than “summarizing meeting minutes, generating reports, and assisting computers with coding.” It added that it was “skeptical” that large tech companies would continue to buy the chipmaker’s graphics processing units in such large quantities.

Locking up billions of dollars in AI-focused data centers without a clear exit strategy for these investments once the AI craze fades only increases systemic risk in the financial world and the economy. Now that data center investments are fueling economic growth in the US, the economy has become dependent on a handful of companies that haven’t yet generated a single dollar of profit from the “computing power” generated by these data center investments.

America’s risky geopolitical gamble fails

The AI boom (bubble) developed with the support of both major political parties in the US. The vision of US companies pushing the boundaries of AI and achieving GenAI first is widely shared—there is even bipartisan consensus on the importance of the US winning the global AI race. America’s industrial capacity is heavily dependent on a number of potential hostile nation-states, including China. In this context, America’s lead in GenAI is seen as a potentially very powerful geopolitical lever: if America succeeds in achieving AGI first, the analysis goes, it could gain an overwhelming long-term advantage over China in particular (see Farrell ).

That’s why Silicon Valley, Wall Street, and the Trump administration are doubling down on the “AGI First” strategy. But astute observers are pointing to the costs and risks of this strategy. Notably, Eric Schmidt and Selina Xu, writing in the August 19, 2025, issue of the New York Times, worry that “Silicon Valley has become so obsessed with achieving this goal [AGI] that it is alienating the public and, worse, missing crucial opportunities to use the technology we already have. By fixating solely on this goal, our country risks falling behind China, which is far less concerned with creating AI powerful enough to outperform humans and far more focused on using the technology we already have.”

Schmidt and Xu are right to be concerned. Perhaps the plight of the US economy is best captured by OpenAI’s Sam Altman, who fantasizes about putting his data centers in space: “Maybe we’ll build a big Dyson sphere around the solar system and say, ‘Hey, there’s actually no point in putting this on Earth.’” As long as such “hallucinations” about using solar-powered satellites to harvest (unlimited) stellar energy continue to convince gullible financial investors, the government, and users of the “magic” of AI and the AI industry, the US economy is surely doomed.