The Betrayal of Britain’s Daughters

How fear of being called racist allowed the largest child-protection scandal in modern British history to flourish for decades.

Many girls are terrified and with reason … a girl had her tongue nailed to the table when she threatened to tell.

— former government advisor, Daily Mail, 2008

There are crimes so extreme that the mind instinctively rejects them, not because they are implausible, but because accepting them would require acknowledging a collapse of morality too large to comprehend. Child sexual abuse is one such crime.

Child sexual abuse does not arrive in a single form. It ranges from isolated abductions, to organised pornography networks, to violence carried out by parents or those entrusted with care. Every one of these crimes is horrific, and none should ever be minimised or ignored.

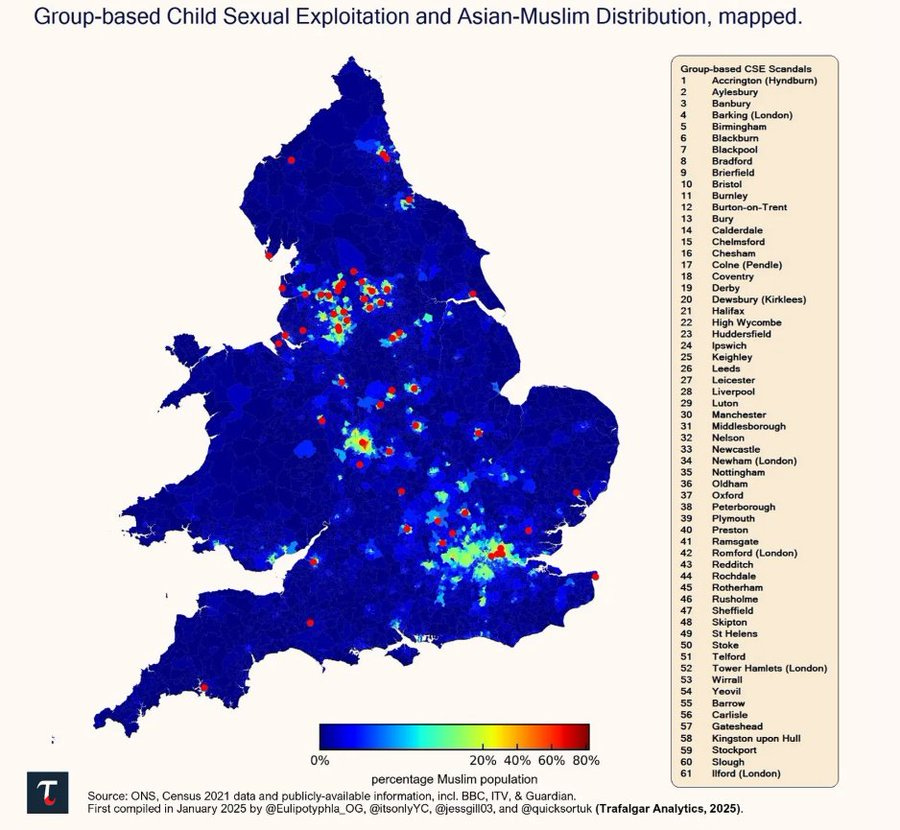

But there is one form of abuse that stands apart, not because it is worse in kind, but because it was allowed to flourish unchecked. The organised targeting of schoolgirls by groups of men who lingered outside schools, fast-food outlets, and transport hubs, grooming children into addiction, sexual exploitation, and prostitution, constituted a distinct and recognisable pattern of abuse.

This pattern was not hidden. It was not unknowable. And yet for longer than a quarter of a century, British authorities chose not to act. Despite the issue being raised at a national level as early as 2003, and despite its presence being well understood in certain towns since at least the late 1980s, it was deliberately sidelined, minimised, and left to metastasise.1

For decades, these gangs were allowed to congregate openly around school gates without consequence. What shielded them was not ignorance or lack of evidence, but an institutional terror of confronting anything that carried racial implications; the shade of their skin protected them.

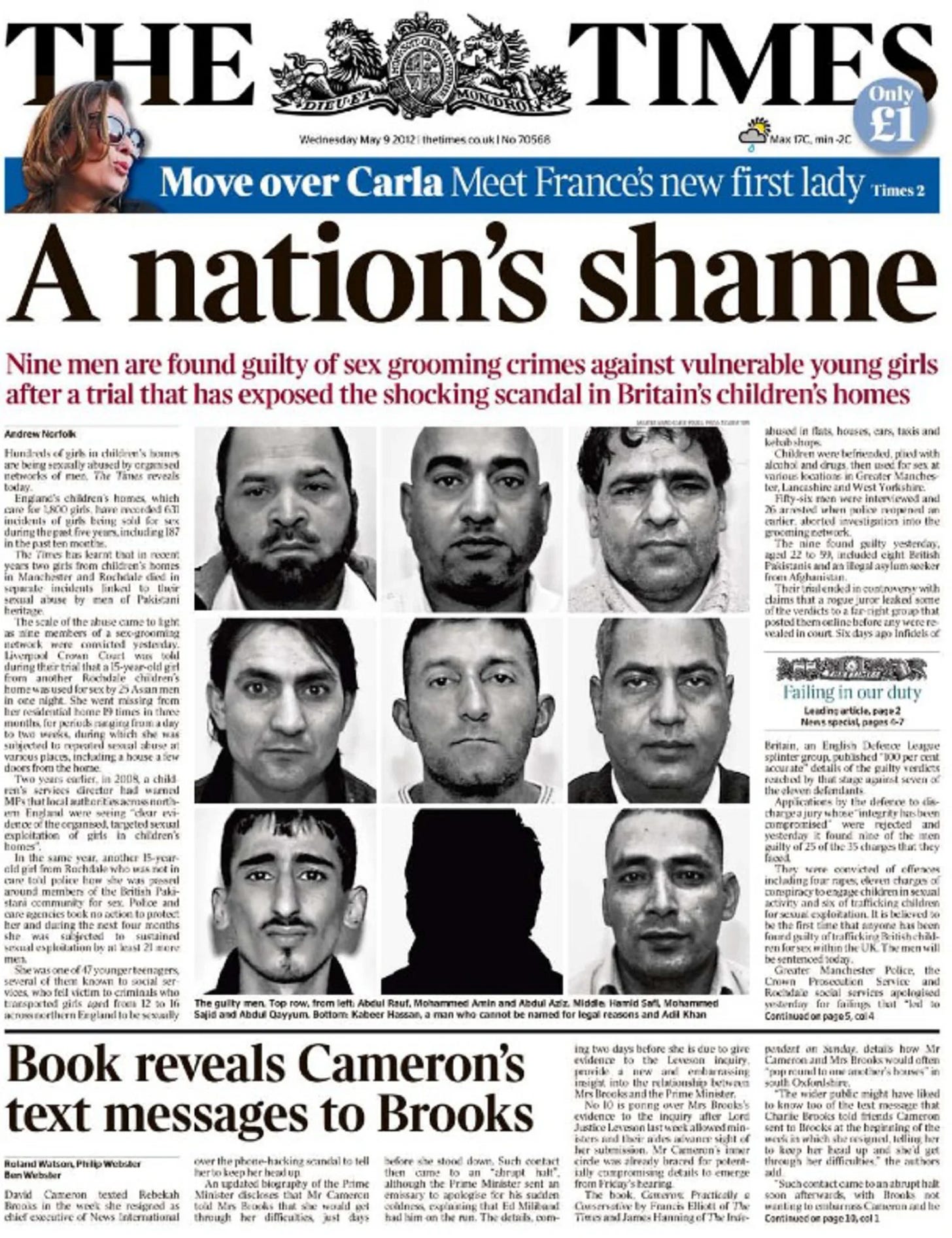

By 2011, the long-standing silence surrounding the issue began to break. Once the initial barrier was breached, the extent of the abuse became increasingly difficult to suppress.2 Over the following years, British media outlets published a succession of detailed investigations that brought the scale of the crimes into public view.

In September 2012, The Times published an extensive overview of the phenomenon.3 The paper reported that for more than a decade, organised groups of men had been able to groom, exploit, and traffic girls across multiple towns and cities in Britain, often operating with minimal interference from authorities.

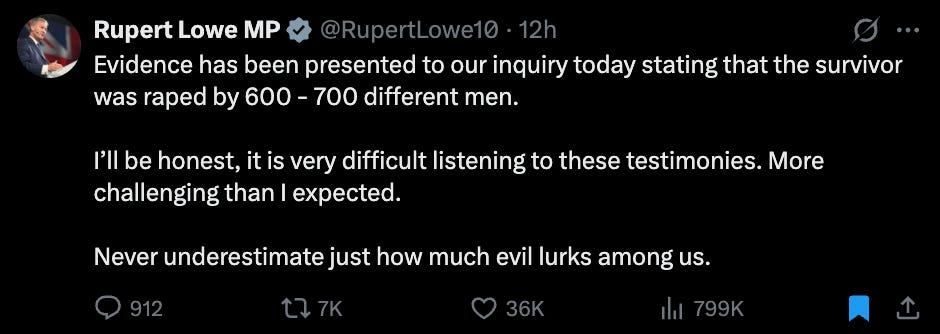

Yet, event The Times underestimated the scale of this. By early 2015, senior police figures were publicly acknowledging the scale of the crisis. One officer spoke of “tens of thousands” of current victims of grooming gangs. A Member of Parliament, representing a constituency widely associated with the problem, went further, suggesting that the total number of victims nationwide, past and present, could reach as high as one million.4

These figures are almost impossible to comprehend. They refer to school-aged girls systematically identified, isolated, and exploited over many years. And yet, despite the magnitude of the harm, perpetrators were able to operate with remarkable impunity.

By the end of 2014, the Association of Chief Police Officers confirmed that the number of victims each year ran into the tens of thousands.5 Even on the most conservative interpretation, this would place the number of victims over a twenty-year period well into six figures. Against this backdrop, the number of successful convictions, under 200, stands as a staggering indictment of the system meant to protect the vulnerable and enforce the law.

There is no comparable serious crime in modern Britain where the disparity between victims and convictions is so extreme.

The question, then, is unavoidable: how could an abuse network of this scale persist for decades, across multiple towns and institutions, without decisive intervention?

Across policing, social services, local government, and related professions, many officials felt unable to speak frankly about the defining characteristics of the problem. Not because those characteristics were unclear, but because acknowledging them carried perceived risks, to careers, professional standing, and social legitimacy. The boundaries of what could be said narrowed to the point where silence became the safer option.

This produced a self-reinforcing cycle. As fewer people were willing to speak openly, institutional inaction deepened, and the cost of dissent appeared ever higher to colleagues and peers.

In some instances, professionals were directly cautioned against drawing attention to ethnic or cultural patterns. In most, it appears such warnings were unnecessary. The fear of being accused of racism ensured that, for decades, there was little formal recognition of the grooming-gang phenomenon as a distinct and systemic form of abuse.

That the victims were overwhelmingly young white schoolgirls, while the perpetrators largely muslims with darker skin, proved decisive, not in prompting action, but in paralysing it. This dynamic allowed abuse networks to operate with remarkable freedom, even as evidence accumulated.

So again, to ask the central question: how could an abuse network of this scale persist for decades without decisive intervention?

The answer is stark in its simplicity. It was not fear of the crime that silenced authorities, but fear of a word: racist.

The Cultural Roots of Predation

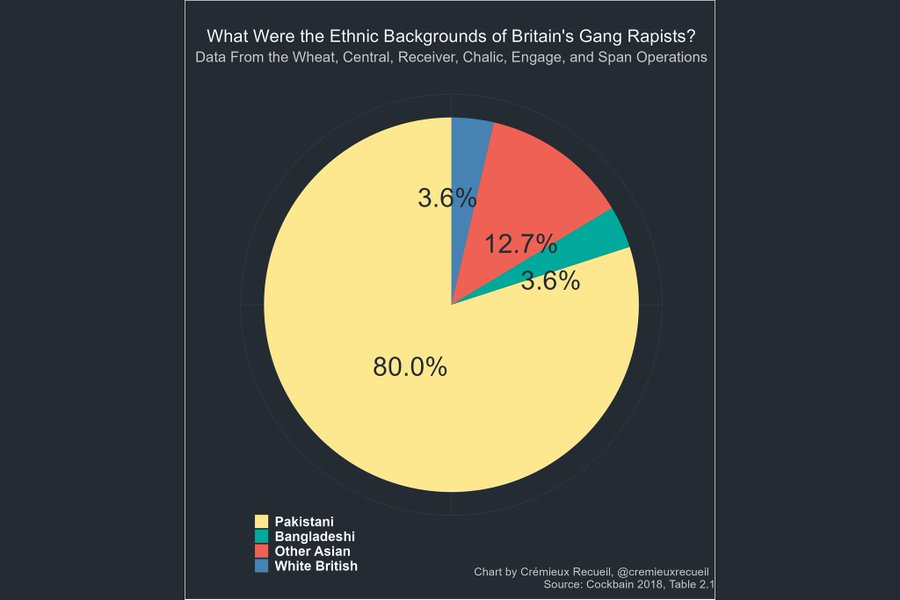

To understand the scale and nature of the grooming gang scandal, one must first confront the cultural context from which the perpetrators emerged. The statistical overrepresentation of men from Pakistani and other South Asian heritages in these specific group-based exploitation networks has been documented by multiple inquiries and judicial remarks.6 The abuse is rooted in a specific worldview imported from rural, patriarchal societies where the status of women is determined by rigid codes of honour (sharaf) and where non-Muslim or “out-group” women are viewed through a lens of religious and racial contempt.7

Central to this incompatibility is the existence of a dual morality within the perpetrator networks. While the women within their own communities are often cloistered and protected to maintain family “honour,” Western women, particularly those who are liberated or vulnerable are viewed as “immodest” and therefore “fair game” for sexual predation.8 This perception is reinforced by the use of dehumanising language, such as the term “kuffar” (non-believer) or “khal” (black/outsider), which serves to strip the victims of their humanity and justify their exploitation.9

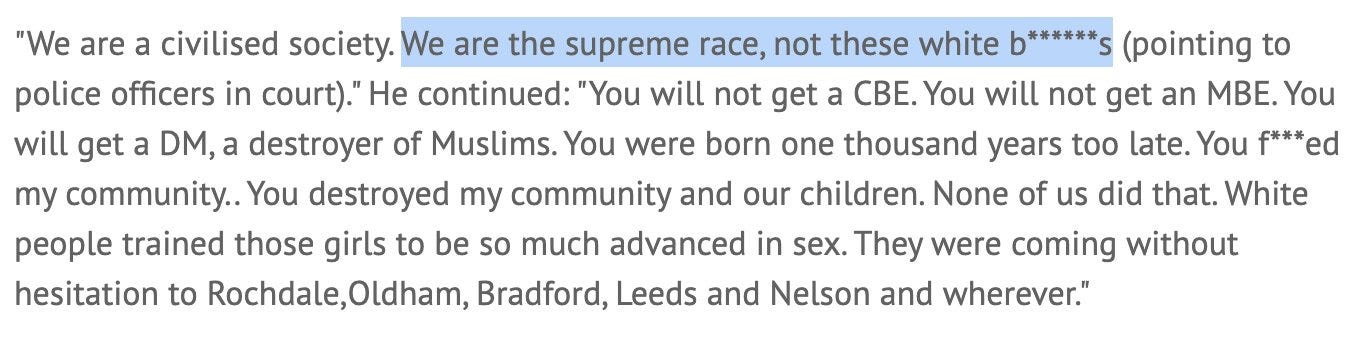

Perpetrators in Rochdale were explicitly told by Judge Gerald Clifton that their treatment of victims was influenced by the fact that the girls were “not of your community or religion”.10 This judicial acknowledgment confirms that the selection of victims was not random but was driven by an “us versus them” mentality that prioritised tribal and religious identity over the laws of the host nation. The victims were not only objects of sexual desire but symbols of a “conquered” or “inferior” culture to be dominated.11

The frequent use of racial slurs such as “white trash,” “white slag,” and “white meat” indicates a racialised hierarchy in which the victims were viewed as having no inherent value.12 In Keighley, a victim reported that when she attempted to stop working as a drugs courier for her abuser, she was called a “little white slag” and a “little white bastard” while being raped.13 These terms are ideological markers that define the victim’s place in the perpetrator’s worldview, a place of total subservience and worthlessness.

The “easy meat” comment, famously referenced by former Home Secretary Jack Straw, validated the experiences of thousands of girls who had been told by their abusers that they were “trash” who would never be believed by the authorities.14

Jack Straw further lamented:

“[T]here is a specific problem which involves Pakistani heritage men… who target vulnerable young white girls. We need to get the Pakistani community to think much more clearly about why this is going on and to be more open about the problems that are leading to a number of Pakistani heritage men thinking it is OK to target white girls in this way… These young men are in a Western society… and they see these young women, white girls who are vulnerable, some of them in care… who they think are easy meat.”

This psychological warfare ensured that victims felt isolated from their own society, believing that even their own government viewed them with the same contempt as their captors.

Rotherham: The Holocaust of Childhood and the Failure of the State

Rotherham serves as the ground zero for the grooming gang scandal. Between 1997 and 2013, Professor Alexis Jay’s independent inquiry concluded that “at least 1,400 children” were sexually exploited in this single South Yorkshire town, explicitly described as a conservative estimate because the inquiry could not quantify the children abused but never known to authorities.15

The Jay Report did not reveal a hidden crime. It revealed a known crime, known in fragments, known anecdotally, known through repeated warnings, that metastasised for years because the people with power treated it as administratively inconvenient and politically dangerous. In the wake of the report, central government language itself became unusually blunt: ministers publicly acknowledged “management failures” so severe that Rotherham Council required external inspection and intervention.16

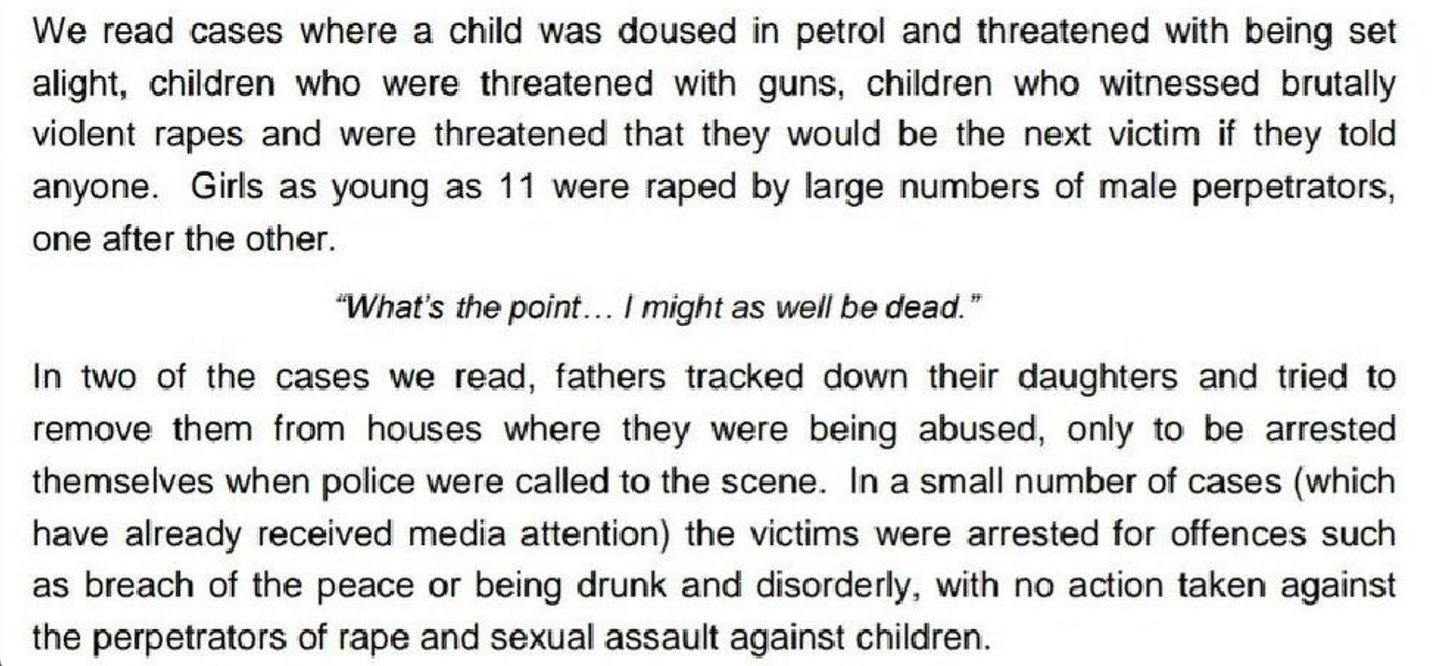

The violence in Rotherham was characterised by a level of sadism that transcended sexual gratification. Children were doused in petrol and threatened with being set alight if they resisted or spoke to the authorities.17 Some were told they were “one bullet away from death.” Others were beaten with extreme brutality. This threat of immolation, alongside the use of firearms and forced witnessing of violent assaults, was designed to create a climate of total terror. The message was clear, the gang possessed the power of life and death, and the British state was powerless to intervene.

One [schoolgirl] was still so frightened of her attacker that she initially refused to give evidence for fear he would hurt her again. She had been raped and prostituted at 11 by a man who bought her little gifts and showed her the first affection she had known.

— Daily Express, 2013

Victims described being “passed around like a parcel” between men, often raped by multiple perpetrators in rapid succession in cars, flats, and wasteland.18 The sheer scale of the involvement, hundreds of men participating in the abuse of a single cohort of girls suggests that the exploitation was a normalised social activity within the perpetrators’ subculture. The victims were commodified, treated as currency to be traded for favours, drugs, or status.

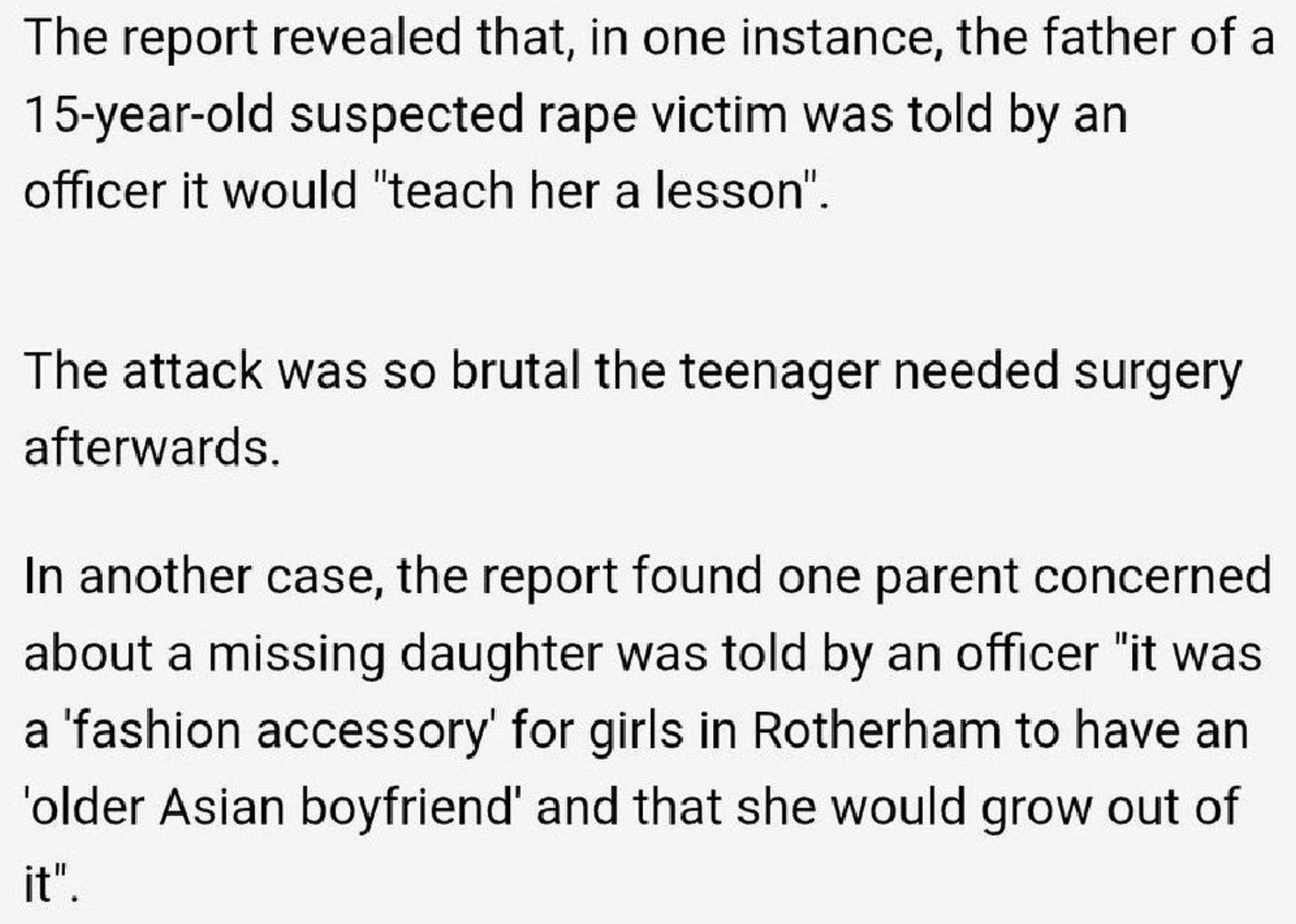

The most damning aspect of the Rotherham scandal was the institutional response. For years, frontline workers who attempted to raise the alarm regarding the ethnic profile of the perpetrators were silenced.19

What made the Jay Report so confronting was not only the sheer scale of abuse uncovered in Rotherham, but the clarity with which it exposed a stark imbalance between who was being targeted and who was committing the crimes. The findings confirmed a pronounced mismatch between the ethnic background of the victims and that of the perpetrators.

Census data from 2011 showed that Rotherham’s population was overwhelmingly white, around 92 per cent, while the largest non-white group, Muslims identifying as Pakistani or Kashmiri, comprised roughly three per cent. Yet the report concluded that the majority of identified offenders were of Pakistani heritage.

What had long been dismissed by campaigners and institutions as a “racist myth” was, in fact, documented reality, one that had been recognised as early as the late 1980s but repeatedly minimised rather than confronted.

In the aftermath of the Jay Report, a further inquiry was launched under the leadership of Louise Casey. This investigation commenced on 10 September 2014, barely three weeks after the Jay findings were made public. The Casey Inquiry was framed as a response to the council’s apparent unwillingness to fully accept the conclusions of the Jay Report.

By this stage, it had become increasingly difficult to portray Rotherham as an isolated anomaly. The Casey Review instead sought to reassert the idea that what had occurred there was exceptional, narrowing the focus and reshaping the narrative in a way that aligned more closely with prevailing media commentary.

The fallout from the Jay Report was immediate and severe. Rotherham Council came under intense national scrutiny, and senior figures began to resign. The council leader, Roger Stone, the chief executive, Martin Kimber, and the director of children’s services, Joyce Thacker, all stepped down shortly after the report’s publication. By early 2015, the scale of institutional upheaval had become impossible to ignore.

The Casey Review revealed a culture of “denial and silence” within the council, where officials actively suppressed information to avoid “giving oxygen” to the political right or damaging community cohesion.20

In some cases, the word “Pakistani” was literally “Tippexed out” of reports to obscure the truth.21 Social services frequently categorised victims as making “lifestyle choices,” a euphemism that blamed the children for their own rape.22 This language allowed the state to wash its hands of responsibility, framing the abuse as a series of “wayward” decisions by teenagers rather than a coordinated campaign of predation by adult men.

Telford: Murder, Arson, and the Longest Failure

While Rotherham garnered international attention, the abuse in Telford was arguably more entrenched and deadly. The Independent Inquiry into Telford Child Sexual Exploitation revealed that over 1,000 children had been exploited over a period of 40 years, dating back to the 1970s.23

The defining horror of the Telford scandal is the murder of the Lowe family in 2000. Lucy Lowe, a 16-year-old girl who had been abused since she was 13 and had already given birth to her abuser’s child, was killed in an arson attack alongside her sister Sarah and mother Eileen.24 The fire was set by Azhar Ali Mehmood, a 26-year-old taxi driver and Lucy’s primary abuser.

The inquiry found that the death of the Lowe family was subsequently used by grooming networks as a terrifying warning to other girls in Telford. Victims were told, “Look what happened to Lucy,” a threat that effectively silenced a generation of survivors.25 This use of mass murder as an enforcement tool demonstrates the extreme brutality of the networks and the total failure of West Mercia Police to recognise the context of the arson as part of a wider trafficking operation.

A survivor known as “Telford Girl” described her experiences in her book, recounting how she was made into a “white slave” who was repeatedly tortured and forced to be “some Muslim man’s wife”.26 She testified that her abusers would “pray openly in the next room to where they raped me,” finding the practice acceptable within their own moral framework. She described the abuse as a “pit of horror” where she was subjected to threats with knives and guns held to her head.27

The inquiry also noted that offenders were “emboldened” by the absence of police action, which they correctly interpreted as a “blind eye” being turned to their activities. This emboldenment led to perpetrators being “bold and open in their offending,” confident that the state’s fear of racial sensitivity would protect them from prosecution.

Oxford: Operation Bullfinch and the Rituals of Degradation

The Oxford scandal, uncovered by Operation Bullfinch, shattered the illusion that grooming gangs were a problem confined to the post-industrial North. Within weeks of the Casey report’s publication, it emerged that investigations in Oxford had uncovered at least 300 victims of grooming gangs. While this figure may appear less severe than the 1,400 victims identified in Rotherham, such a comparison becomes more revealing when viewed in demographic context. In 2011, Muslims made up 3.1 per cent of Rotherham’s population, whereas in Oxford they accounted for just 0.75 per cent.28

The Oxford scandal revealed a network of depravity operating in one of the world’s most prestigious university cities, utilising ritualistic torture to break the wills of its victims.29

The abuse in Oxford involved elements of ritualistic humiliation that suggested a deep-seated sadism. One victim, “Girl A,” described being stripped, cut with a razor to collect her blood, and having her body hair shaved off.30 She was then forced to lie in a closed coffin and made to eat a raw chicken heart, an act designed to destroy her humanity and bind her to the gang through terror and shame.

Victims were routinely threatened with having their “throats cut” if they did not comply, and were told they were “owned” by the gang.31 Judge Peter Rook QC, in his sentencing remarks, noted that the perpetrators had “ripped the soul” out of their victims, causing immense psychological harm including PTSD, anxiety, and depression.32 One victim, AB, was taken to the remote Shotover Woods as punishment for “lying about having her period,” where she was forced to give oral sex to multiple men in the pitch black before being abandoned.33

Many of the Oxford victims were in the care of the local authority, living in care homes that became primary hunting grounds for the gangs.34 The perpetrators deliberately targeted girls in care, knowing they were less likely to be believed by the authorities. They loitered outside schools and care homes, using gifts of alcohol and drugs to lure the girls into their cars.35

The Serious Case Review found that agencies suffered from “institutional disbelief,” consistently failing to view the girls as victims of organised crime.36 Instead, they were viewed as “troublesome” or “wayward” adolescents, a categorisation that absolved the state of its duty to protect them. This failure was compounded by the fact that many of the men were significantly older than the girls, yet the police frequently treated the “relationships” as consensual despite the obvious presence of grooming and coercion.37

Rochdale: “Easy Meat” and the Justice System Weaponised

The Rochdale case provides the clearest example of how the justice system was often weaponised against the victims, further entrenching the sense of abandonment felt by the working-class community.

The central witness in the Rochdale trial, “Girl A,” was subjected to a double victimisation: first by the gang, and then by the state.38 She was trafficked to over 50 different men, treated as a commodity to be sold for sex in flats, cars, and takeaways. In a move of staggering incompetence or malice, police officers advised her to apply for criminal injuries compensation before the trial had even concluded.39

The defence team later used this application to argue that she had fabricated the abuse for financial gain, effectively turning the state’s own advice into a weapon used to destroy her credibility. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) initially dropped the case against her abusers, deeming her an “unreliable witness”. It was only after a new prosecutor, Nazir Afzal, reversed the decision that justice was finally pursued. Afzal later noted that authorities had ignored the abuse because they viewed it as a “cultural” issue that they were afraid to touch.

The Infrastructure of Abuse: Taxis, Takeaways, and Care Homes

In nearly every major grooming scandal, the taxi industry served as the primary logistics arm of the networks. In Telford, Rotherham, and Rochdale, taxi drivers were the individuals responsible for trafficking girls between towns and transporting them to the men who had paid for access.40 In Rochdale, drivers from the Eagle Taxis firm were at the heart of the trafficking ring.41

The licensing authorities consistently failed to act on intelligence reports indicating that taxi drivers were involved in exploitation. A “nervousness about race” prevented councils from revoking the licenses of predominantly Asian drivers, even when police had flagged them as suspects.42 Consequently, vehicles that were often paid for by the state to provide school transport were instead used as mobile brothels.

Takeaway shops, particularly those open late at night, served as the primary sites of initial contact between groomers and their victims. In Peterborough, a restaurant owner named Mohammed Khubaib used his business and rental properties to target girls as young as 12.43 He luring them with free meals and tobacco before taking them to flats where they were forced to drink vodka and perform sexual acts.44

In Blackpool, the disappearance of Charlene Downes, aged just fourteen, remains one of the most disturbing unresolved cases linked to Britain’s grooming-gang scandals. Charlene vanished in November 2003 after spending time in the town centre, an area known at the time for the presence of adult men loitering near takeaways and transport hubs, targeting vulnerable schoolgirls.

The investigation soon focused on the Funny Boyz takeaway, where Charlene had reportedly been seen shortly before she disappeared. Two men who worked at the premises were later charged, not with her murder, but with unrelated sexual offences involving minors. The two men were Iyad Albattikhi, a 29-year-old man from Jordan and the owner of Funny Boyz fast-food outlet and Mohammed Reveshi, Albattikhi’s business partner and landlord.45

During the course of those proceedings, testimony emerged that shocked even seasoned investigators. Witnesses alleged that the defendants had joked about Charlene’s fate, laughing that she had been “grinding it up into kebab meat”.46

The phrase itself became infamous, not because it was ever legally substantiated as fact, but because of what it revealed about mindset. Whether uttered as a grotesque boast or a cruel taunt, the remark reflected an extreme moral collapse, a child reduced to consumable matter, her humanity erased entirely.

The criminal trial ultimately collapsed due to evidentiary and procedural failures, leaving no convictions for Charlene’s disappearance and no definitive account of what happened to her. Her body was never found. Her family was left without answers. And the public was left with something arguably more corrosive than uncertainty, a growing sense that the system was incapable of confronting crimes that sat at the intersection of child abuse, organised exploitation, and racial sensitivity.

In the years since, the “kebab meat” comment has taken on a symbolic weight far beyond the courtroom. It has come to represent the total dehumanisation evident in many grooming-gang cases: white, working-class girls viewed not as children worthy of protection, but as disposable objects “meat” to be used, traded, and discarded. It also stands as a stark indictment of institutional paralysis.

Multiculturalism and the “Tippex” Incident

The consistent failure of British institutions to address these crimes for over three decades cannot be attributed to incompetence alone. It was the result of a deliberate ideological framework that prioritiSed the “sensitivity” of minority communities over the protection of the indigenous working class.

Baroness Louise Casey’s National Audit on Group-based Child Sexual Exploitation revealed an “appalling lack of data” regarding the ethnicity of perpetrators.47 She found that questions about ethnicity were “asked but dodged for years” to avoid “appearing racist” or raising community tensions.

The most symbolic discovery of the audit was the “Tippex” incident as mentioned above, where investigators found case files where the word “Pakistani” had been literally covered with white-out. This physical erasure of the truth perfectly encapsulates the state’s strategy, if the ethnicity of the rapists is hidden, the ethnic and cultural roots of the predation can be ignored. This obfuscation allowed the Home Office to release reports in 2020 claiming that perpetrators were likely “majority white,” a conclusion Casey labeled “hard to understand” and “un-evidenced”.48

The political left, which traditionally positions itself as the defender of the vulnerable, faced a state of “cognitive dissonance” when the perpetrators were identified as members of a minority group and the victims as the “white working class”.49 Sarah Champion, the Labour MP for Rotherham, was forced to apologise and resign from her frontbench position for writing an article stating that “Britain has a problem with British Pakistani men raping white girls”.50

This enforcement of political correctness ensured that the truth remained a “taboo” within the very party that should have been protecting the girls. The state prioritised the feelings of the “sub-communities” of the predators over the lives of the “white trash” victims, a hierarchy of victimhood that left tens of thousands of girls to rot in the “pits of horror” described by survivors.51

The price of Silence

An entire generation of young white schoolgirls across England has been sacrificed on the altar of multiculturalism. Each year, in dozens of towns, new cohorts of girls were deliberately targeted by organised grooming networks, approached with money, attention, and feigned affection, often too young to recognise that these gestures were only the first stage of systematic sexual exploitation. The cumulative evidence suggests that the British state, in its pursuit of multicultural “harmony,” fostered a permissive environment in which the most extreme forms of abuse could flourish unchecked.

Within this moral vacuum, the fear of being labelled racist became the groomers’ most reliable shield. Political correctness actively paralysed those institutions tasked with preventing them. Police, social services, councillors, and safeguarding bodies hesitated, delayed, and ultimately failed, less out of ignorance than out of terror of reputational damage. In this climate, predatory networks learned that silence could be enforced not through intimidation alone, but through the self-censorship of the state itself.

As the United Kingdom moves toward a long-overdue national inquiry, the lessons of Rotherham, Telford, and Oxford must not be diluted or forgotten. These were not isolated breakdowns, nor accidents of history. They were the predictable consequence of an ideology that placed “social cohesion” above child protection and national sovereignty, and punished those who spoke the truth before it was safe to do so.

https://celina101.substack.com/p/the-betrayal-of-britains-daughters