The Big Lebowski

There cannot be a more perfect example of mass gaslighting than the 1998 Coen brothers’ film The Big Lebowski. By inverting sloth, fecklessness, penury, and alcoholism into admirable qualities—essentially making it cool to be a loser—this film offers up the Jewish ideal for a gentile in the character of the Dude. He’s laid back, utterly harmless and tolerant, and any aggression he may abide (such as that of his corpulent friend Walter with his buzzcut, tinted glasses, and fishing vest) will be militantly pro-Jewish. Could there possibly be a white person less threatening to diaspora Jews than this? And since the film was so well made, millions of young Americans took the bait and played along, transmogrifying it from a cult hit into a cultural phenomenon. The Dude may seem like a loser, and his life may seem petty, squalid, and pointless, but with Coen Bros. movie magic, the audience is gaslit into believing the opposite. No, no, the Dude is not a loser, he’s a role model. And his life is pretty awesome if you think about it. He’s got style, man. He doesn’t care what people say about him. He doesn’t think about tomorrow. He takes it easy. He doesn’t hurt anybody. Live and let live, you know?

I’m sure that gaslighting American whites into celebrating maladaptive behavior was not part of the Coen brother’s conscious plan. I say this because the film coheres well as art, in and of itself. It is Seinfeldesque in its bizarre banalities, quirky characters, and jarring scene changes. Its dream sequences are memorably surreal, its pacing spot on, its wild-west narration ironically quaint and superfluous, its lines eminently quotable. I especially admire the soundtrack, which is exquisite, not only in its selection across a wide range of genres but in how specific songs become associated with specific characters throughout the film. It even includes a composition by Moondog.

The Big Lebowski is, simply put, a film of inspired vision. It also faithfully follows the Hollywood film noir convention of an outsider being drawn deeper and deeper into an unbelievable web of intrigue where nothing is as it seems. See Chinatown or The Long Goodbye for relatively recent examples, or The Big Sleep if you’re in the mood for something classic. This, and the performances are all superb. Since little in The Big Lebowski comes across as deliberate propaganda, I think Joel and Ethan Coen simply wanted to make a cool movie about a cool dude. In the eyes of millions, this is exactly what they did. And that’s too bad, because the devil could not have made a better film than The Big Lebowski.

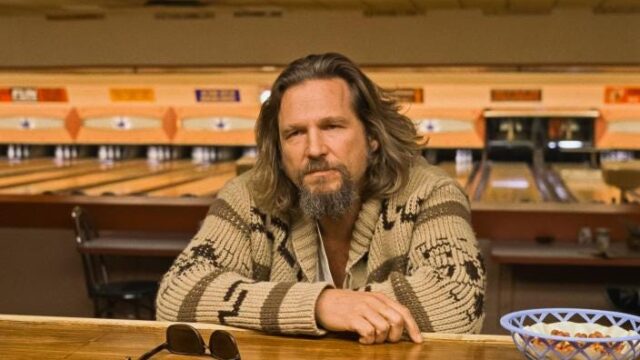

We start off following a tumbleweed as it rolls across a bushy desert and then into the streets of Los Angeles. Sam Elliot’s cowboy narration over folksy Western harmonies tells us he has a mighty fine yarn to spin, but as the middle-aged Dude (played seamlessly by Jeff Bridges) slouches through a supermarket in a bathrobe, sunglasses, and sandals, sniffing cartons of Half & Half, we realize this isn’t so. The only concrete thing Elliot—known as the Stranger—can tell us about the Dude is that he rejected his given name (Jeff Lebowski), he’s lazy, and that he fits in with his time and place. “Sometimes there’s a man,” the Stranger repeats obliviously, apropos, apparently, of nothing.

The conflict begins when a pair of thugs ambush the Dude in his apartment, jam his face into the toilet, and demand money. We soon learn that it’s a case of mistaken identity. Bunny, the wife of another Jeff Lebowski (who happens to be a paraplegic millionaire), owes money to a shady character named Jackie Treehorn. The thugs realize their mistake and leave, but not without peeing on the Dude’s rug. This rug is the story’s prime mover, its oddball McGuffin. It apparently “tied the room together,” yet we never get a good look at it or the room. Because of the rug’s alleged value, Walter persuades the Dude to approach the other Lebowski and demand compensation for his rug. (It seems neither character has heard of the multitude of products which can clean pee stains off of rugs—as most pet owners already know.)

And here begins the plot proper, which involves an unlikely confluence of kidnappings, ransoms, embezzlements, porn videos, severed digits, stolen cars, German nihilists, Italian comedians, decadent artists, and lots of bowling amid a never ending stream of profanity. Things just get weirder and weirder as the Dude, egged on by the psychopathic Walter, learns more and more about the truth. And because the ensuing entertainment is so original and so inspired—and the soundtrack so expertly compiled—The Big Lebowski coaxes us into a hazy pleasure realm of the absurd.

The Big Lebowski’s primary sin, however, is to never make the Dude the butt of a joke. We are never meant to laugh at him, as sloppy, flabby, inarticulate, and hapless as he is. Instead, however, we are encouraged to laugh at everyone he encounters. We laugh at Walter (splendidly played by John Goodman) as he attempts and invariably fails to control his ever bubbling rage. We can also laugh at his anal-retentive philo-Semitism. We can laugh their know-nothing friend Donnie (a simple role played by the highly overqualified Steve Buscemi) as he hopelessly tries to follow their bowling-alley discussions. We can laugh at John Turturro’s skin-tight lavender jump suit and voluptuous Puerto Rican accent. We can laugh at the Dude’s landlord because he can barely fit into his sweat clothes and does performance art and is too timid to press the Dude for his rent despite being 10 days late. We can laugh at Jeff Lebowski’s callous can-do attitude, his assistant’s smarmy obsequiousness, his daughter avant-garde pretensions, her giggling assistant’s pencil-thin mustache, his trophy wife’s nymphomania, as well as her flamingly gay German friends (formerly of the fictitious 1970s krautrock band Autobahn). Compared to this eclectic clown show, the Dude actually comes across as normal. Thus, we are never really tempted to laugh at him. With him, maybe. But not at him. I mean, he smokes grass and listens to Creedence. That’s not funny, man. That’s cool.

This implies quite strongly that the Dude is perfectly fine the way he is. The Coen brothers then take it step forward by giving him a righteous past and having him spout politically correct opinions. When Lebowski’s assistant (embodied by a painfully grinning Phillip Seymour Hoffman) shows the Dude a photograph of his employer with numerous black children, he identifies them as Lebowski’s children. They are really the beneficiaries of Lebowski’s charity, but the Dude assumes that they are his biological children and concludes that “racially [Lebowski] is pretty cool.” He then reveals that in college he had been part of campus protests, smoked a lot of pot, and occupied administrative buildings. Later in the film he admits to Lebowski’s daughter Maude (played by a serenely cold Julianne Moore) that he was one of the Seattle Seven and had been a signatory of the Port Huron Statement. The original Port Huron Statement, the Dude points out, “not the compromised second draft.”

All of this gives the Dude impeccable leftist credentials and puts him beyond ridicule, regardless of how much he deserves it. It also insulates The Big Lebowski from devolving into farce. Things have gotten just a little too real for that. For point of comparison, imagine not laughing at say, Nigel Tufnel from This is Spinal Tap (1984) or Tugg Speedman from Tropic Thunder (2008), two other highly successful comedies directed by Jews, but ones that actually show respect for their gentile subjects. We laugh at these characters for their obvious vanities and foibles, but as their stories unfold, they overcome their limitations to work with others in positive, creative endeavors. These characters are ridiculous, sure. But they have room for redemption, and eventually strive in that direction. Not so with the Dude. The Dude has no need for redemption because he is already perfect. He’s the Greek god of slackers, the joint-smoking avatar of the Buddha. How can you possibly improve upon that?

And so we drill directly to heart of gaslighting that is The Big Lebowski. In reality, the Dude would be a pathetic waste of life. He’s middle aged, out of shape, unemployed, directionless, financially irresponsible, constantly drinking and smoking pot, and making stupid decisions. And the single productive thing he does with his time (i.e., bowling), we don’t even see him do. Aside from one moment in a dream sequence, the Dude never once rolls a bowling ball. All he does in the bowling alley is sit on his ass and make vacuous conversation. So we don’t even know if he was ever good at anything. Such a person is plainly a loser (something the Dude himself does not deny after pulling his sunglasses out of the toilet and putting them on). Having a son or daughter like this would be heartbreaking for any parent. This is the truth. Despite this however, the Coen brothers use all their talents to hold up these bad qualities as good like a poisoned apple and ask the audience, “Don’t you want to be like the Dude?”

And we’re supposed to accept that it is a mere coincidence that the filmmakers in this case are Jews? From the Jewish diaspora perspective, a gentile like the Dude is the complete opposite of the Frankfurt School’s “authoritarian personality.” He has no religion, no ounce of patriotism, no family to speak of. He has renounced his past, and has no children and so he has no stake in the future. That, and he is a former socialist. Such a person would never turn on Jews by reverting to fascism, conservatism, or any other right-leaning mode of thought—to say nothing of race realism. Any such system would rightfully reject human detritus like the Dude. But not the Frankfurt School. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer would certainly have abided the Dude—as I am sure the Dude would have abided them. Again, I don’t claim the Coen brothers deliberately tried to subvert Western civilization with The Big Lebowski. Rather, I speculate that they had internalized the Frankfurt School’s sociological and psychological theories of anti-Semitism to the point that for white people “cool” meant anything that can’t possibly be seen as “authoritarian.”

And if gentiles are tempted to shift towards authoritarianism anyway, well, then there’s Walter to emulate—an unhinged, gun-toting jarhead who’d been in ‘Nam and is willing to execute ultra-violence upon the enemies of Jews. The Coens give us an absurd example of this in the film’s climax when Bunny’s German nihilist friends burn the Dude’s car and attack him in a berserker rage, all while shrieking “I fuck you in the ass!” For a stereotype to be funny, it has to be based at least somewhat in truth. Here, we don’t even have that. Nazis were never like this. And neither were the Kraftwerk performers on which the Coens based their German villains. All we have is a figment of the their feverish Nazi obsession, so common among left-wing Jews today. This Walter is merely a neocon’s attack dog, chomping at the bit for violence and spouting jingoistic tidbits of Jewish history.

And if you’re a gentile and neither of these characters suits your fancy, then you can be like Donnie: meek, empty-headed, and easily distracted by middlebrow activities like bowling.

It can be argued that I am taking The Big Lebowski more seriously than it is meant to be. But because it was so well made that it actually spawned a wide-reaching cultural movement, I must take it seriously. (Believe me, I don’t want to. I disliked the film when it came out, and I dislike it even more today.) I have the 10th anniversary DVD, and in the bonus material interviews Bridges claims that among Buddhists, the Dude is considered to be a Zen master. Ironically or not, this signifies a kind of reverence where there should be no reverence. Buscemi states flatly that “everybody wants to be the Dude.” He explains further, “We just love him so much, and what a wonderful way to go through life.” The actors further explain how The Big Lebowski has become a sort of Star Trek for slackers, spawning an obsessive following that even they don’t understand. There’s also a yearly festival. These fans call themselves “achievers,” and are never shy about flapping their gums at the actors about their favorite movie. As of 2008, Buscemi believed that more people had seen this film than any other he’d been in.

Turturo is much closer to the truth than he realizes when he states:

College kids are not going to classes because of The Big Lebowski. And I blame this all on Joel and Ethan. And that’s why our society is in crisis, because of The Big Lebowski. The Dude, what kind of example is he?

He’s kidding, of course. But does he lie?

And Lebowski Fest is real. Starting in 2002 in Louisville, Kentucky with 150 participants, it went on for 16 years in 14 cities. Fans would gather at bowling alleys for film showings, alcohol consumption, socializing, and of course bowling. People dressed up, not only as characters from the film, but as props or imagery or even the minutest of miscellanea. The Star Trek comparison is apt. In the DVD’s documentary of a Lebowski Fest in Las Vegas, many achievers are recorded gushing over the movie. Three stood out for me. One was a baseball player, one was a bearded man in a white robe holding a pair of tablets, and one was in camouflage gear with his face painted brown. Who are they? Well, the first two are the embodiment of Walter’s speech in which he extols 3,000 years of Jewish achievement from Moses to Sandy Koufax. And the third is a reference to Walter’s buddy in ‘Nam who died face first in the mud.

There’s even a religion based on the Dude. It’s called Dudeism. Or the Church of the Latter-Day Dude, if you’re not all that into the brevity thing, to paraphrase the Dude himself. According to Wiki:

Dudeism’s stated primary objective is to promote a modern form of Chinese Taoism, outlined in Tao Te Ching by Laozi (6th century BCE), blended with concepts from the Ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus (341-270 BCE), and presented in a style as personified by the character of Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski in the film.

Make of this what you will.

Earlier I wrote that little in The Big Lebowski comes across as deliberate propaganda. That’s because one part of the film is deliberate propaganda. In the end, the Stranger addresses the audience to sum up the film. And after the Dude says his famous line, “The Dude abides,” the Stranger says, “I take comfort in that. It’s good knowing that he’s out there, the Dude, takin’ ‘er easy for all of us sinners.”

So there you have it—the Coen brothers telling you directly to like the Dude, despite all that’s so obviously unlikeable about him. And that’s gaslighting, something that absolutely nobody should abide.