The Fate of Ordinary White Rhodesians

A Housewife’s Killing on the Copperbelt (1960)

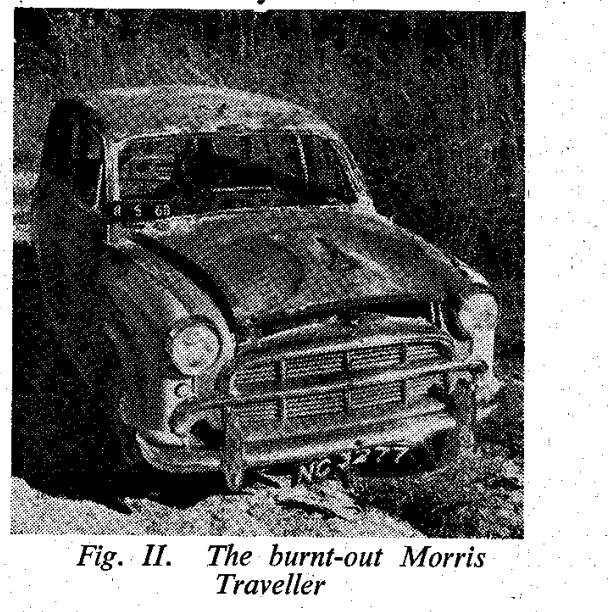

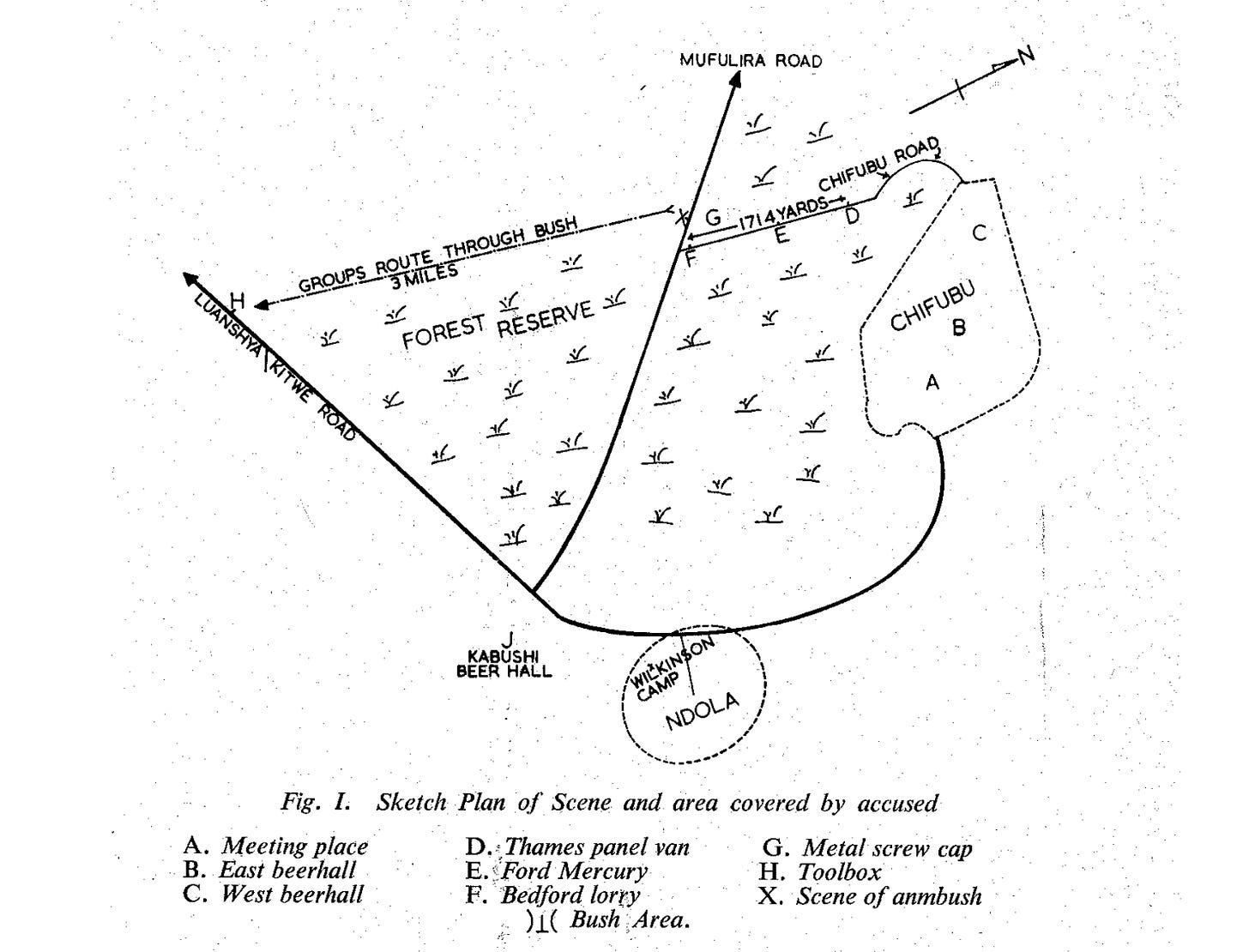

On 8 May 1960, a brutal flashpoint erupted on Northern Rhodesia’s Copperbelt. Lilian Margaret Burton, a 39-year-old white settler and housewife, was driving near Ndola with her two young daughters, Debbie, aged 12, and Rosemary, aged 4, when their car was ambushed by a violent unruly mob of African nationalist activists associated with Kenneth Kaunda’s newly formed United National Independence Party (UNIP).12 The attackers surrounded the vehicle, hurling stones and striking it with sticks. A large rock smashed through the windscreen. One of the men leapt onto the bonnet and poured petrol into the driver’s side of the car. Throughout the assault, Mrs Burton and her children, along with their dog, remained trapped inside, stunned and struggling to comprehend what was happening. Mrs Burton shouted desperately for the mob to move aside. The children screamed and clung to her. The dog barked frantically in defence. Petrol soaked her clothing, its fumes choking the interior of the car.

Then Lilian saw a match struck and thrown inside.

The vehicle was engulfed in flames almost instantly. The two children managed, with great difficulty, to escape through the passenger side. Their mother, now ablaze, followed them out of the burning car. The dog was not so fortunate. Trapped inside, its fur caught fire; it continued barking until it was burned alive.

As Mrs Burton staggered away from the wreckage, her hair and clothes still alight, she was met not with help but with laughter. Her assailants slapped and kicked her as she crawled along the ground, nearly naked, crying out, “God, help me!” They eventually left her for dead.

Later that morning, an African charcoal burner found her collapsed in the bush and stopped a passing motorist, who rushed her to Ndola Hospital.3

What happened next was extraordinary. As she lay mortally injured, Mrs. Burton urged restraint. According to contemporaneous reports, she implored her fellow European settlers not to take revenge on Africans in retaliation for her fate.4 Before succumbing to her wounds, Burton is said to have pleaded that her “misfortune” not be answered with attacks on Africans nationalists. This act of suicidal forgiveness was echoed by her husband, Robert Burton. Grief-stricken, Mr. Burton told the press that his wife died an ardent supporter of African nationalist political aspirations and harboured “no ill-feelings” toward Africans even in death.5 He passionately appealed to both Africans and Europeans “not to use her death for political purposes”.6 In effect, the Burton family, longtime liberals sympathetic to black liberation and nationalism, hoped to prevent this tragedy from spiralling into wider racial bloodshed. Their stance embodied a liberal ideal of tolerance and reconciliation amid extreme provocation by violent African nationalists.

Settler Outrage and Demands for Justice

Despite the Burtons’ appeals, the immediate political aftermath of the Burton atrocity was explosive. News of the attack sent shockwaves through Northern Rhodesia’s white community (as well as the broader Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland). Conservative white settler reactions combined indignation, horror, and deepening mistrust of African nationalism (rightfully so).7 Within days, impromptu vigilante meetings sprang up across the Copperbelt8. At one such gathering of over 2,000 Europeans in Kitwe, vented their fury and fear. Government officials joined the chorus: Northern Rhodesia’s Territorial Minister, Rodney Malcomson, and Commerce Minister, Frank Owen, took the podium to denounce the UNIP militants responsible as “heartless ‘rats’ and murderers.” They openly endorsed the crowd’s clamours for “arms” and “action” against African nationalists.9 The ministers even assured the audience that federal Prime Minister Roy Welensky “would exterminate the ‘rats’” himself if the colonial Governor failed to crack down.10

White settler newspapers amplified these sentiments. The Northern News (a Copperbelt tabloid loyal to Welensky’s United Federal Party) ran coverage of the Burton murder, reflecting the overwhelming European public opinion.11 Editorials and letters bristled with revulsion at the “primitive savagery” of the attack.12 Settler leaders demanded that authorities respond with uncompromising force. The United Federal Party (UFP), which dominated the colonial legislature called for the immediate resignation of Governor Sir Evelyn Hone, accusing him of tolerating UNIP “hooliganism” and being too weak to deal with the “UNIP terrorists” who attacked an “innocent housewife and mother.”13 The implication was clear, in settlers’ eyes, Hone’s moderate approach and the broader liberal policies of London were endangering white lives. The European Mineworkers’ Union echoed these views, representing the perpetrators as “simple-minded, half-savage mobsters” led by “vociferous and clamorous” demagogues.14 Many settlers rightfully viewed the murder not as an isolated crime but as proof of an existential threat posed by militant African nationalism.

Galvanised by Burton’s killing, conservative Europeans pressed for drastic measures. Public meetings and UFP officials urged the colonial state to “meet UNIP violence with violence”.15 They demanded collective punishment of anyone involved, tighter security laws, and harsh penalties for convicted assailants. In particular, settler opinion insisted that those responsible must face the death penalty.16 There were calls to outlaw UNIP entirely, criminalise seditious propaganda, and even arm white civilians in self-defence. Some even invoked the memory of earlier colonial conflicts, urging Rhodesian women to mobilise for community defence “as the women in South Africa did during the Boer War” underscoring how deeply the incident tapped into real racial fears.17

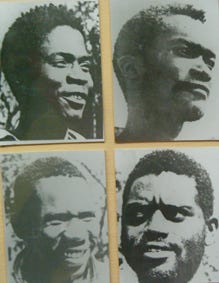

The colonial authorities did act decisively against the offenders, though not in the vigilante fashion some settlers desired. An intensive police investigation (later recounted by senior officer D. M. Brockwell as “The Burton Atrocity”) rounded up the culprits over the ensuing weeks.18 Four UNIP activists, Bernard Chanda, James Phiri, Robin Kamima, and Matthew Ngebe were ultimately charged and tried for Mrs. Burton’s murder.19 After a marathon trial (the longest and costliest in Northern Rhodesian history), all four men were found guilty. In April 1961, the trial judge sentenced them to death.20 Appeals were exhausted by November, and on 23 November 1961 the convicted killers were hanged at Central Prison in Livingstone, 18 months after the attack. Settler communities greeted the executions with satisfaction. To them, justice had been served and a message sent. Yet beneath that sense of vindication lay an abiding bitterness that liberal colonial governance had allowed matters to reach this point in the first place.

Nationalist Narratives: Freedom Fighters or Savages?

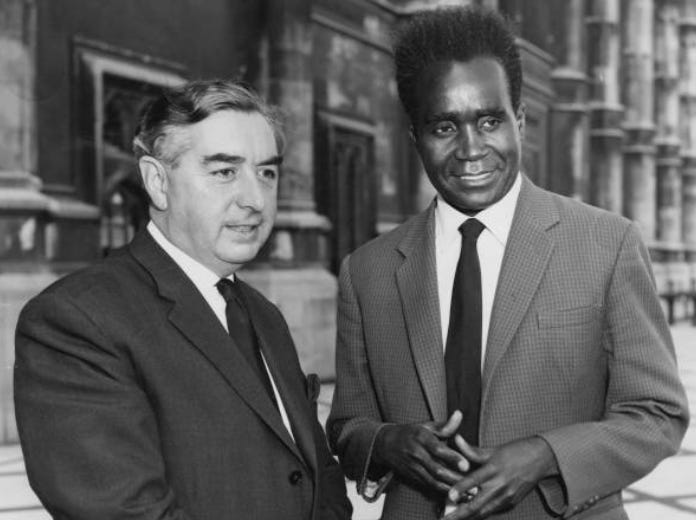

As furious settlers mourned Lilian Burton as a martyr of their civilisation, African nationalist leaders scrambled to control the narrative among their own constituents. UNIP’s response to the murder was ambivalent and telling. Publicly, Kaunda and other high-ranking UNIP officials disavowed the killing, they did not want to be too closely associated with the brutal death of a woman and mother. Some party leaders blamed “unruly elements” for the attack, suggesting it was not sanctioned by UNIP’s top brass.21 But at the same time, they were determined that rivals and colonial authorities not use the incident to discredit UNIP or halt the independence momentum.22 In private and in party propaganda, UNIP strove to contextualise, if not outright justify, Burton’s fate as a tragic consequence of colonial oppression. Kaunda himself reportedly portrayed Mrs. Burton’s death as “the unfortunate consequence” of the settlers’ and British government’s refusal to dismantle the Federation and grant Africans majority rule.23 By this logic, the colonial regime’s intransigence (not UNIP’s tactics) was ultimately to blame for the violence. This framing exonerated UNIP, the party presented itself as fighting a just anti-colonial war in which occasional brutalities, were to be expected so long as freedom was denied.24

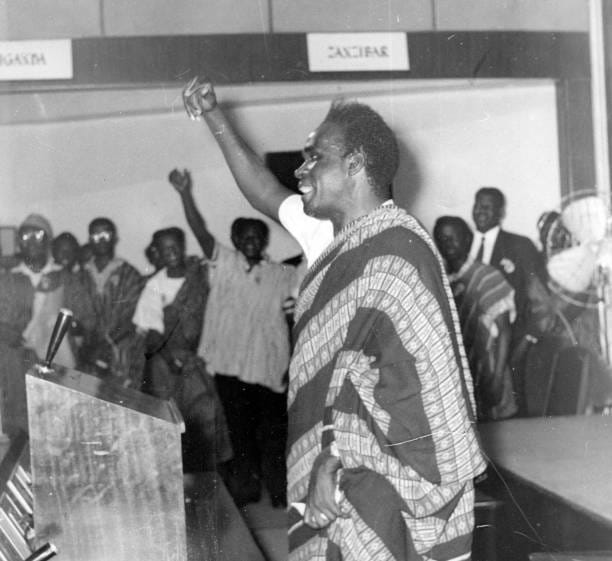

Indeed, in the nationalist press and rhetoric, the convicted attackers were not simply seen as common criminals. Within months of the trial, UNIP’s newspapers and activists were hailing the condemned men as political heroes. Party publications openly celebrated those convicted of Burton’s murder as “political martyrs.”25 This startling glorification, noted with alarm by colonial officials treated the prisoners as freedom fighters who had given their lives in the struggle against colonial rule. A question raised in the British House of Commons in February 1962 pressed the Colonial Secretary on “what action [was] to be taken against members and publications of UNIP which have hailed those convicted of this atrocious murder as political martyrs”.26 The response from London was non-committal; unless such statements violated criminal incitement laws, there was little the government would do.27 To staunch anti-communist critics like MP Biggs-Davison, this leniency epitomised a naïve liberal indulgence of extremism. From UNIP’s perspective, however, the elevation of the Burton killers to martyr status was a propaganda coup, one that kept the base mobilised and defiant. It signalled to African audiences that the party considered itself at war with colonialism, and those who shed blood (even of innocents) were soldiers, not murderers.

https://celina101.substack.com/p/the-fate-of-ordinary-white-rhodesians