The Knife: Rediscovering Roman ‘Bully’ Culture

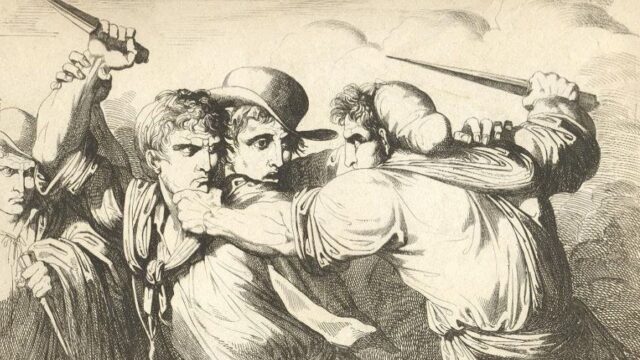

Costantino Ceoldo and Danilo Rossi explore the edges of Europe’s folkloric underground, viewing the culture of the knife-wielding “bullies” of Rome through the lens of popular honor and the warrior archetype in contrast to the vulgar street crime of today’s degraded cities.

Knives and short blades, razors, lampposts, and scissors, the latter perhaps for a purely feminine crime of passion — when one thinks of these bladed weapons, even improper ones, one instinctively sets aside the chivalrous ideal, with its rituals and duties. Instead, one’s feet stand firmly planted in the beaten earth of the most authentic populace, the people in an alley or a secluded square who confront what the nobles could afford in other places more befitting their social status (sober, perhaps, and with greater consensus).

Let’s say it: people like duels with swords or pistols, but knife fights? The short blade has always been the emblem of hired assassins hidden in the shadows, of chicken thieves who will always and only remain such, of hotheads uselessly engaged in a personal and fruitless search for a noblesse destined to be without oblige.

Just like the Roman bullies, some would say. And here our thoughts immediately turn to the stories of Rugantino and Mastro Titta from two centuries ago. But for Danilo Rossi Lajolo di Cossano, the bullies of Rome were a real psychosocial phenomenon, with intentions and ways of behaving totally different from those of the Neapolitan guappi, the Milanese bauscia, and the Calabrian capibastone, a phenomenon considered so interesting that he ended up dedicating a book to it, published by the Italian publishing house Magenes.

So, if the bullies weren’t just poor criminals engaged in extortion and bullying of poor people not much different from themselves, then who were they and what were they looking for? Danilo Rossi himself tells us, commenting on his literary endeavor that began with a train journey to Rome.

The history of Roman bullies through the eyes and words of a blade master

Costantino Ceoldo: When did your passion for knives and their history begin?

Danilo Rossi: My passion was born from the stories of my uncle Clemente, who told me about his adventures and experiences around the world, at a time when adventure was just around the corner. Then, over time and with the experience I gained, I embarked on a journey of learning, venturing throughout Italy in search of masters who were the guardians of ancient family traditions.

What important and influential figures did you meet?

In my past, I had the opportunity to meet various figures who in some way changed my approach. I certainly owe a lot to Master Nino Mannino, who introduced me to that substratum of Sicilian tradition. The maestro left us years ago, but I still carry his kindness and passion in my memories.

Where has your research taken you?

My research has mainly taken me to the south, where some aspects are the remnants of that apparent nobility which criminals at the time took pleasure in having, all legends with the sole purpose of justifying their criminal actions.

If the nobleman fights with a sword, what does the commoner fight with?

The nobleman mainly fights with his head, sword, or stick, which are the natural extension of his limbs. The commoner, on the other hand, fights with his heart, fearless and contemptuous of his own life, courageous, bold, and violent. He must be given greater emphasis by the tools that everyday life provided him: these ranged from scissors to axes, from knives to razors, to stones, and so on. Over time, the knife became the weapon more associated with criminals than with commoners.

In the collective imagination, isn’t the man with the knife more treacherous than the soldier or the swordsman?

Then as now, the knife is feared more. This can be traced back to the most ancient and remote part of human nature: the knife has always been the tool of ingenuity and evolution. This is also due to the dangerous nature of the object itself and what it normally caused, wounds and death, so this aspect inherent in our evolutionary history has influenced humankind to such an extent that fear takes shape at the mere sight of it.

Could you draw a comparison between the Italian tradition of knives, which is multifaceted and varies from region to region, and that of other countries? I am thinking of East Asia and blades such as the karambit, made famous by certain imported films.

First of all, we must consider that Italian and European traditions have contributed radically to the formation of other cultures. If we look at the army of Spain in the 15th century, we see that the famous elite group, the Tercios, included Italians: Sicilians, Campanians, and Lombards. They were expert fighters, hired by Spain at the time. In the Philippines, amid various clashes, they somehow shaped and influenced the forms of combat. Currently, the Kali method deals with the sword and dagger, a purely Italian derivation. Being a people of artists, we gave birth to the Flos Duellatorum in the 15th century, with the master Fiore dei Liberi di Premariacco. This speaks volumes about our abilities, but going even further back, we think of the Sherden, the Sardinians in the pay of Pharaoh Ramses I, and we could continue with many other important documented stories about what we have done and how we have changed the way of fighting in many populations from Latin America to Asia.

Frenchman Bernard Lugan believes it would be a good idea to reintroduce duelling and has written a book about it. What do you think?

It would certainly be interesting, but unfortunately it remains only a utopian idea. Duelling is relegated to a bygone era, when men were Men with a capital M. Today, it is difficult to expect such individuals to exist. Society changes, and with it, customs change. Today, duelling can perhaps be found in a sporting version with disciplines such as MMA, boxing, and short fencing (of which I was a creator and promoter for many years, establishing the first federation of this sport in Russia).

Let’s talk about your latest work. Why dedicate a book to Roman bullies? Who were they really?

Er Cortello (The Knife) is my tribute to the last true bullies of Rome of yore, when honor mattered and fights were between rivals one-on-one, unlike today when the term is used to refer to modern-day criminals. The Roman bully had nothing to do with today’s bullies, individuals who attack a single person in a gang, steal, and often kill just for fun. The Roman bullies of the 19th and 20th centuries were of a different breed: they were guardians of the people of the district. And so, fascinated by their deeds as recounted by Trilussa and other influential writers, I couldn’t help but immerse myself in that substrate dusted by time and pay homage to them.

How were they different from other popular, seemingly similar figures?

As mentioned, they were people of a certain stature, people who wanted to redeem themselves in a society where abuse by the powerful was the order of the day. Just think of The Marquis of Grillo, the allegorical but realistic film starring Alberto Sordi. His famous line sums up the whole historical period: “I am me and you are a fuck”. Rude, yes, but actually realistic.

In your book, you define Roman bullies as a real psychosocial phenomenon. Can you explain this idea?

If we analyze the era and the areas, we can see that there are some aspects that differentiate the protagonists. The Bulli di Roma, as mentioned, were pure, sometimes naive, but proud and kind-hearted. If, on the other hand, we take the Camorristi or the Neapolitan guappi, we can see a different characteristic: they sought power, they were extremely intelligent in their criminality, they were individuals whose thoughts were fundamentally linked to the Domingo and power. This can still be seen today, where the guappi of the past are now the organized Camorristi of our day.

Isn’t there a risk of going from one extreme to the other? From uncouth brigands to romantic, tormented, and misunderstood heroes?

These are two different aspects. The brigands were criminals who formed gangs to rob travelers. They often created a halo of legend around themselves, passing themselves off as leaders, as knights protecting the people, but fundamentally they were just criminals of the worst kind, nothing like the heroic Roman bullies whose attitudes may certainly have been an expression of the violence of the time, but who were still men of heart. We Italians are all a bit like that: boastful, rowdy, boisterous, sometimes violent, but always warm-hearted.

How did the state and society of the time react to bullies?

The state often used them, as did the papacy. Bullies were often used to gain favors or fame. Think of Cicceruacchio, Angelo Brunetti, the heroic Roman bully of the district who gave his life for the papacy. Examples like these are present in the history of bullies and can also be found in the context of the 20th century. Just think of Gramsci and his Letters from Prison, where he expresses his feelings for the prisoners who proved their fighting skills in order to pay homage to him for his (involuntary) presence in the country’s prisons. Literature is full of examples like this.

For the last question, I will take an easy cue from the daily news. Who and what are modern “bullies”? How should we treat them when we encounter them?

As mentioned, modern “bullies” today have nothing to do with those of the past. Today, they are dangerous to society, lacking in ethics and morals, the product of a sick society where honor, courage, and heroic deeds no longer hold sway. Today, there is only the attitude of the bully on social media, but in fact, they are nothing more than cowardly criminals, and the only treatment reserved for them is repatriation or prison.

https://www.arktosjournal.com/p/the-knife-rediscovering-roman-bully