The MAHA Moment

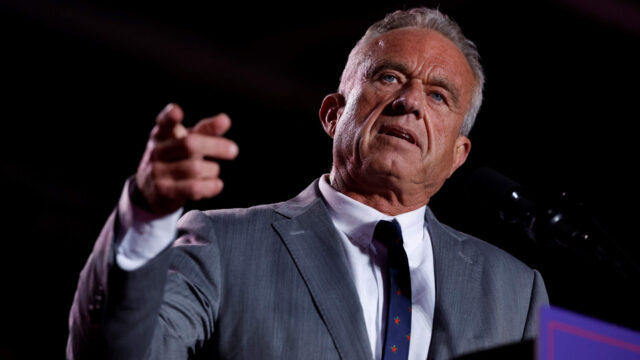

The expectation among seasoned D.C. professionals was that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. would quickly fade in his tenure as Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). He was too idealistic, his ideas were too fringe, and the gulf between his base and Trump’s was too vast to bridge. And anyway, the vast sprawling bureaucracy of HHS—which housed 82,500 career bureaucrats when Kennedy assumed the role—would swallow him up.

But Kennedy had something that the Washington consensus failed to take into account, something that the bureaucracy didn’t have: a popular movement and a level of backing from the president that has surprised political observers.

It’s easy to forget that Kennedy pulled in millions of votes as an independent presidential candidate before throwing his support behind Trump in August 2024, a move that likely shifted the outcome of the election in key swing states. His messaging about chronic disease and corporate capture resonated across traditional political lines. But Kennedy did not just bring votes: he brought an energetic grassroots network that spanned the whole country. His rallies drew crowds that dwarfed those of other third-party candidates, feeling less like political gatherings and more like a great social movement.

Kennedy’s campaign and his subsequent alliance with Trump represent something genuinely threatening to the established political order: an expansion of Trump’s base of support beyond the rural working-class voters that journalists have spent years writing think pieces about. These journalists don’t have to go on a safari to Pennsylvania or West Virginia to find them—they are their neighbors, their yoga instructors, and the people they sit next to at farm-to-table restaurants. Trump’s inroads into this demographic suggest that the Democratic coalition’s hold on affluent urbanites might be more fragile than they want to admit.

Part of the reason Trump’s second-term actions have met with much less visible resistance from the ruling class is that Secretary Kennedy has created a halo effect, softening their perception of the administration. Kennedy’s willingness to take on powerful industries and his obvious passion for protecting children have made it harder to maintain the caricature of Trump’s government as purely malevolent.

Take actor Chris Pratt’s recent appearance on Bill Maher’s podcast. “I’d hate to be so mired in hatred for the president that any success from his administration is something I’d have an allergic reaction to. To be like, ‘Oh, well, if they do it, I don’t want it to happen. I’ll put Clorox in my children’s cereal myself…’” It’s the kind of comment that would have been unthinkable from a Hollywood A-lister during Trump’s first term. Now, it barely made a ripple.

And the crunchy-to-MAGA pipeline is not just a one-way conduit. MAGA culture itself has shifted. Traditional Trump supporters—people who would have rolled their eyes at “wellness culture” a decade ago—are now cutting out junk food, conscious of environmental toxins, and questioning the recommended vaccine schedule.

Cleaning the Augean Stables

Since being confirmed as secretary, Kennedy has used his platform aggressively. Nowhere has this been more evident than in his willingness to confront the bureaucrats who have spent decades building fiefdoms within the health agencies. He’s fired thousands of employees across HHS and its subsidiary agencies, treating the bloated bureaucracy as an organization in desperate need of restructuring.

The individual targets have been equally dramatic. Kennedy has shown no hesitation in removing obstructionist officials. Take his handling of Dr. Christine Grady, the chief of the Department of Bioethics at the National Institutes of Health—and the wife of Dr. Anthony Fauci. Kennedy made it clear that if she wanted to remain at HHS, she would have to accept a transfer to Alaska.

Or take his ouster of CDC Director Susan Monarez, who had defied HHS directives to change the CDC’s COVID-19 vaccine recommendations. Kennedy also pushed out close Fauci ally and NIAID Deputy Director for Clinical Research Dr. Clifford Lane, along with Dr. Peter Marks from the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

As heartening as these personnel actions are, however, they only scratch the surface of what needs to be done to hold accountable the federal officials and federally funded researchers whose decisions have compromised public health. Dr. Fauci may be gone, but in his place at NIAID sits Jeffrey Taubenberger, a longtime Fauci ally who conducted the kind of reckless gain-of-function research Kennedy was sent to stop. Taubenberger led work to resurrect the 1918 Spanish flu virus and splice its genes with modern H1N1 strains—research that epitomizes the dangerous hubris of a scientific establishment more interested in what it can do than whether it should. That someone with this record not only remains employed but also holds a leadership position at NIAID underscores just how incremental the progress made thus far has been.

NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya is a good man and a capable physician who spent the pandemic years as an outsider critic of the federal health bureaucracy. But his tenure thus far has been marked by insufficient aggression in removing entrenched career officials who have every incentive to wait him out, slow-walk reforms, and protect their allies. Given that NIH funded and encouraged the research that led to COVID-19, which caused the subsequent deaths of tens of millions and seriously damaged the health of hundreds of millions more, what is needed is not an incrementalist or a reformist approach, but a Carthaginian peace.

Beyond the firings and the personnel battles, Kennedy has moved quickly to deliver tangible policy reforms that resonate with his base. He’s initiated a comprehensive review of the CDC’s childhood vaccine schedule, which will scrutinize the timing, combinations, and necessity of each recommendation. He’s demanded that pharmaceutical companies provide the raw data from clinical trials rather than relying on their summaries, a move that has sent shockwaves through an industry accustomed to self-regulation with minimal oversight.

Kennedy has also been active on food policy. He’s begun the process of revoking “generally recognized as safe” status for dozens of additives, forcing manufacturers to prove safety rather than assuming it. He has also confronted industry on the use of artificial dyes that may have negative health effects. Yet the administration’s victory lap over removing these dyes from ice cream reveals how far the reforms still have to go.

The problem with most ice cream isn’t the artificial coloring—it’s the gums and emulsifiers manufacturers use to replace actual cream. These additives disrupt the gut microbiome, causing intestinal inflammation that can lead to serious chronic health problems. The solution is simple: use real cream, as Häagen-Dazs already does (which explains why their product tastes so much better). But switching to real ingredients would raise prices noticeably, while swapping artificial dyes for natural ones is comparatively cheap.

By declaring victory on artificial dyes, Kennedy and the USDA gave ice cream manufacturers cover to claim clean ingredients while the fundamental problem—replacing traditional ingredients with cheaper industrial substitutes—remains unaddressed. Similarly, Kennedy praised Starbucks for avoiding artificial dyes while ignoring their plastic-lined hot cups, a major source of microplastic consumption.

This points to a broader challenge: while Kennedy has been willing to take on visible targets like artificial dyes, the administration has been more cautious about confronting the deeper structural problems in American food production. Forcing manufacturers to use real ingredients rather than industrial replacements would mean taking on the entire economic model of the American food system—a battle the administration has not yet shown itself ready to fight.

Kennedy has also taken aim at pharmaceutical advertising, one of the most normalized yet bizarre features of American healthcare. The United States and New Zealand are the only two countries in the world that allow direct-to-consumer drug advertising, a fact that becomes striking once you’re aware of it. Kennedy has argued that the practice fundamentally corrupts the doctor-patient relationship, turning medical decisions into sales opportunities and patients into marketing targets. When pharmaceutical companies spend over $6 billion annually convincing Americans to “ask your doctor” about drugs they may not need, the result is overprescription, inflated costs, and a healthcare system oriented around profit rather than health.

It’s no surprise that this proposal has generated fierce pushback from pharmaceutical companies. It is also a large part of why the media has gone after Kennedy with such intensity, since pharmaceutical advertising represents a major part of their revenue streams.

Progress has also been made on animal welfare, an issue that cuts across traditional political divides. Kennedy has moved to phase out mandatory animal testing requirements for drug and cosmetic approval, pushing the FDA to accept alternative testing methods using human cell cultures, computer modeling, and organ-on-a-chip technology. This shift marks an advance in both ethics and effectiveness. Animal models often fail to predict human responses, leading to drugs that pass animal trials but harm humans, or potentially beneficial treatments that are abandoned because they failed in mice. By modernizing testing requirements, Kennedy has united animal rights advocates, efficiency-minded researchers, and cost-conscious pharmaceutical companies, a rare coalition.

The End of the Beginning

The MAHA movement has proven it can take on entrenched bureaucrats and ask uncomfortable questions about food safety and regulatory capture. But there remains significant work in tackling the harder problems that require confronting entire industries and challenging practices so normalized that most Americans don’t realize are harmful.

A structural problem has also emerged: most of the effective execution has been confined to Kennedy’s immediate office at HHS. While the secretary makes bold pronouncements and initiates high-level policy changes, the implementation at subagencies like the FDA and CDC has been inconsistent at best.

Messaging has often been scattered, with different agencies seemingly working at cross-purposes or announcing initiatives without clear follow-through. The lack of a coherent, unified communications strategy has confused supporters who are trying to understand what the administration is actually accomplishing. Many of the career staff who opposed Kennedy’s agenda remain in place at lower levels, quietly slow-walking reforms or finding bureaucratic workarounds to avoid implementing directives from above.

What is needed are MAHA teams of true believers—people who understand the mission at a granular level and are willing to fight for it—who are embedded in each subagency with real authority to make significant changes. The secretary can fire thousands of employees, but if the replacements aren’t mission-aligned and empowered to act, the bureaucracy will simply absorb the shock and continue operating as it always has.

There is also low-hanging fruit that has gone unpicked. The FDA’s policy of encouraging producers to fortify grains and milk, for instance, was designed to combat deficiency diseases like pellagra and beriberi that emerged when the desperately poor survived on virtually nothing but cornmeal or white rice. Those specific nutritional crises are thankfully no longer a problem in America.

But the practice of fortification has remained, and this creates problems for significant portions of the population. Many people lack the genetic ability to properly methylate the synthetic folic acid added to grains, leading to a buildup that can cause health problems. Milk producers use cheap synthetic versions of vitamins A and D rather than ensuring adequate levels through better feed and farming practices. Added iron, particularly in grain products, contributes to oxidative stress. Discouraging the use of such additives would be a straightforward reform that aligns perfectly with MAHA goals.

Another easy win would be to make ivermectin available over the counter. A significant number of Americans are still getting this medication in livestock formulations, which are available without prescription, but are much harder to properly dose.

More challenging is the question of environmental toxins—the pesticides, herbicides, forever chemicals, and plastics that pervade American life at levels unthinkable in other developed countries. While Kennedy has spoken about these issues, the administration’s actions haven’t matched the urgency of the rhetoric. Glyphosate remains ubiquitous. PFAS contamination continues largely unaddressed. Microplastics are showing up in our blood and our brains.

These aren’t peripheral concerns. If environmental factors are truly driving the chronic disease epidemic, these chemicals should be the primary target. Taking them on means confronting industrial agriculture and chemical manufacturers with far deeper pockets and more political influence than food dye producers. It’s understandable why the administration has started with more winnable battles, but at some point, MAHA will need to prove it can take on these harder fights.

Perhaps most notably absent from the MAHA agenda is any serious discussion of light exposure and its impact on health. The circadian disruption caused by artificial light—particularly the blue-spectrum light from LEDs and screens—represents one of the most dramatic environmental changes in human history, occurring over just the past few decades. A recent study found that the introduction of LED light around 2010 has decoupled women’s menstrual cycles from the lunar cycle.

President Trump, a staunch critic of LED lighting, signed an executive order within hours of taking office that directed his administration to remove the Biden Administration’s regulations against incandescent lightbulbs. But there has yet to be a significant return to shelves of those bulbs, and there has been no public health campaign to educate the public.

The movement also needs to expand its agenda to include more conventional health concerns. Tickborne illnesses like Lyme disease and alpha-gal syndrome, which causes life-threatening meat allergies from tick bites, affect hundreds of thousands annually but receive inadequate research funding and lack reliable diagnostics. Tinnitus afflicts millions with debilitating symptoms yet gets minimal federal attention. Chronic pain leaves tens of millions of Americans searching for treatment options beyond opioids, yet non-pharmaceutical approaches remain underfunded and inaccessible. Promising regenerative medicine therapies like stem cell treatments and platelet-rich plasma injections show potential but face regulatory obstacles and lack the rigorous research backing needed for widespread adoption. Confronting these overlooked conditions would prove that the movement’s commitment extends beyond its signature issues to the full spectrum of American health challenges.

Kennedy has demonstrated that reform is possible. The firings, the policy changes, the willingness to confront industry—these aren’t small achievements. But measured against the scale of the crisis MAHA exists to address, they’re a beginning, not a conclusion. The chronic disease epidemic continues. The institutional rot runs deeper than a few thousand terminated bureaucrats. If the movement stops here, it will have failed the families counting on it to deliver real change. MAHA has the platform, the mandate, and the public attention. What happens next will determine whether this was a genuine turning point in American health policy.