The Potent Charm of Weapons and Vaccines

The mesmerizing dramas of war against foreigners and war against infectious diseases are rooted in the same psychology.

The second stanza of the Iliad lets the reader know that this is going to be a story about humans fighting each other. Surprisingly, the primary conflict isn’t the war between the Greeks and the Trojans, but between Agamemnon and Achilles. On top of this destructive conflict, the Greek army is further punished by the plague.

Begin with the clash between Agamemnon—

The Greek warlord, and the godlike Achilles.Which of the immortals set these two

At each other’s throats?

Apollo … offended by the warlord.Agamemnon had dishonored

Chryses, Apollo’s priest, so the god

Struck the Greek camp with plague,

And the soldiers were dying of it.

And so, we see that the first great story of western literature is about humans fighting each other while at the same time being struck with an infectious disease.

In our new book, Vaccines: Mythology, Ideology, and Reality, we show that, from the beginning of the vaccine enterprise in the 18th century, vaccines have been conceptualized as weapons for fighting infectious diseases, while infectious diseases have been conceptualized as akin to an invading army.

To understand the mesmerizing fascination of weapons for the human mind, consider that the United States now spends almost a trillion dollars per year on armaments. Waging war and developing weapons has forever been one of man’s chief occupations and motivations.

The most conspicuous and astonishing feature of the human condition is that—despite all of our advances in developing civilizations that protect us from the hostile elements of nature—we have made zero advances in overcoming our nature to fight each other instead of developing more sophisticated ways for resolving conflicts.

The pointless pissing contests that we see in Eastern Europe and the Middle East are identical to the destructive enmity between Achilles and Agamemnon. When it comes to conflict resolution, mankind has learned nothing since the 8th century BC.

On the contrary, our technological advances in weapons development—especially aircraft, missiles, and drones—have enabled us to depersonalize the enemy far more than the men of the past who struggled hand-to-hand with each other.

I remember my grandfather telling me around the year 1985 that he was still haunted by the sight of the extremely young German soldiers that he killed while he served as an infantry soldier in northern Italy in 1945.

“Some of them were still completely beardless,” he said.

Because they were fighting with rifles and grenades instead of with bombs dropped out of planes, they actually saw each other.

Instead of developing more sophisticated ways to cooperate and resolve conflict, humans prefer to develop ever more destructive weapons to intimidate, destroy, and subdue each other.

The story of man’s war against infectious disease is more complex and paradoxical because, while the medical profession has been completely fixated on vaccine development, the true vanquishers of infectious diseases have been the following major advances that occurred in the West between approximately 1870 and 1943:

1) Nutrition (significant increases in food availability and nutrient content) greatly improved public health and disease resistance. Vitamin D fortification of milk in the 1930s further strengthened children’s immune health. The severity of malnutrition in the past—catastrophic for immune health—is evidenced by the fact that scurvy and rickets were still common among the poor until the 20th century.

2) Public sanitation, with modern sewer systems installed to channel effluent away from cities and their drinking water, largely eradicated cholera and typhoid fever by the year 1900. Public sanitation campaigns in the U.S. against breeding mosquito grounds largely eliminated yellow fever by the year 1906. In the American South, an aggressive public sanitation campaign to build outhouses largely eradicated hookworm by the year 1955.

3) Secure water supply and treatment (filtration and chlorination) infrastructure.

4) Pasteurization, refrigeration, and other hygienic measures for producing, transporting, and storing milk and other food products.

5) Improved housing (better heating, ventilation, and plumbing) for the urban working poor. Water closets, soap, warm water, and detergent for washing bed linens and clothing became standard household amenities.

6) Labor laws reduced hazardous and stressful working conditions, including excessively long hours.

7) Introduction of sulfa antibiotics in the 1930s, penicillin in 1943, and erythromycin in 1952, reduced mortality from bacterial infections including diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus.

As we note in our book:

In his 1988 book, The Origins of Human Disease, the British physician, epidemiologist, and medical historian, Thomas McKeown, made a persuasive case that of all factors, nutritional improvements made the single greatest contribution to the reduction of infectious disease mortality. A well-nourished body with no vitamin deficiencies is very hardy, but it becomes highly susceptible when it is malnourished. In our era of calorie abundance, it is easy to forget that, even in Europe and North America, famine and vital nutrient deficiencies were a common feature of the human condition until well into the 20th century.

McKeown’s thesis seems artistically expressed in Albrecht Dürer’s painting “The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse,” in which Famine (wielding a grain scale) is the central horseman in the charge that tramples man underfoot, and is riding the biggest steed.

HHS Secretary Kennedy is thus on the right track with his endeavor to improve American nutrition by replacing sugary processed foods with wholesome foods with a vastly superior nutrient profile.

In the long story of vaccines, we have arrived at the moment of realizing that they are—like the weapons of war—relatively primitive instruments for improving the human condition.

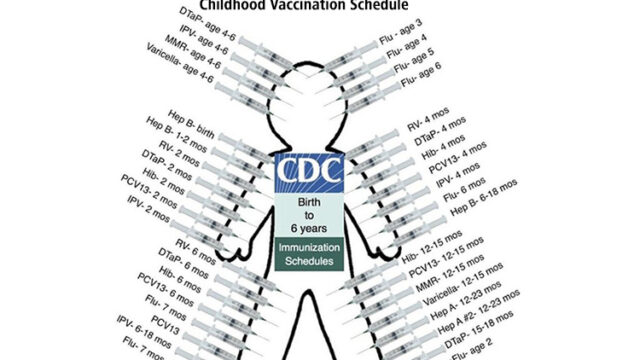

Just as more human ingenuity should be applied to conflict resolution instead of developing more destructive weapons, medical science should seek more sophisticated ways of bolstering the immune system and treating infectious diseases instead of injecting infants with ever larger batteries of vaccines.

The obsessive fascination with vaccines is an intellectual artifact of the 18th century, when humans were still living in extremely primitive conditions.

https://www.thefocalpoints.com/p/the-potent-charm-of-weapons-and-vaccines