The Power of Second Impressions

We all know the maxims about the importance of first impressions—how they stick, how you might never recover if you fail to make a good one. It’s very true that a man must be sharp and ready at all times because certain opportunities come without warning and vanish even faster if one is deemed unworthy. But the maxims don’t capture the whole truth. Though you will never get second chance to make a good first impression, the surprise and delight of a strong second impression—showing a man to possess more depth or force than previously thought—might be even more powerful.

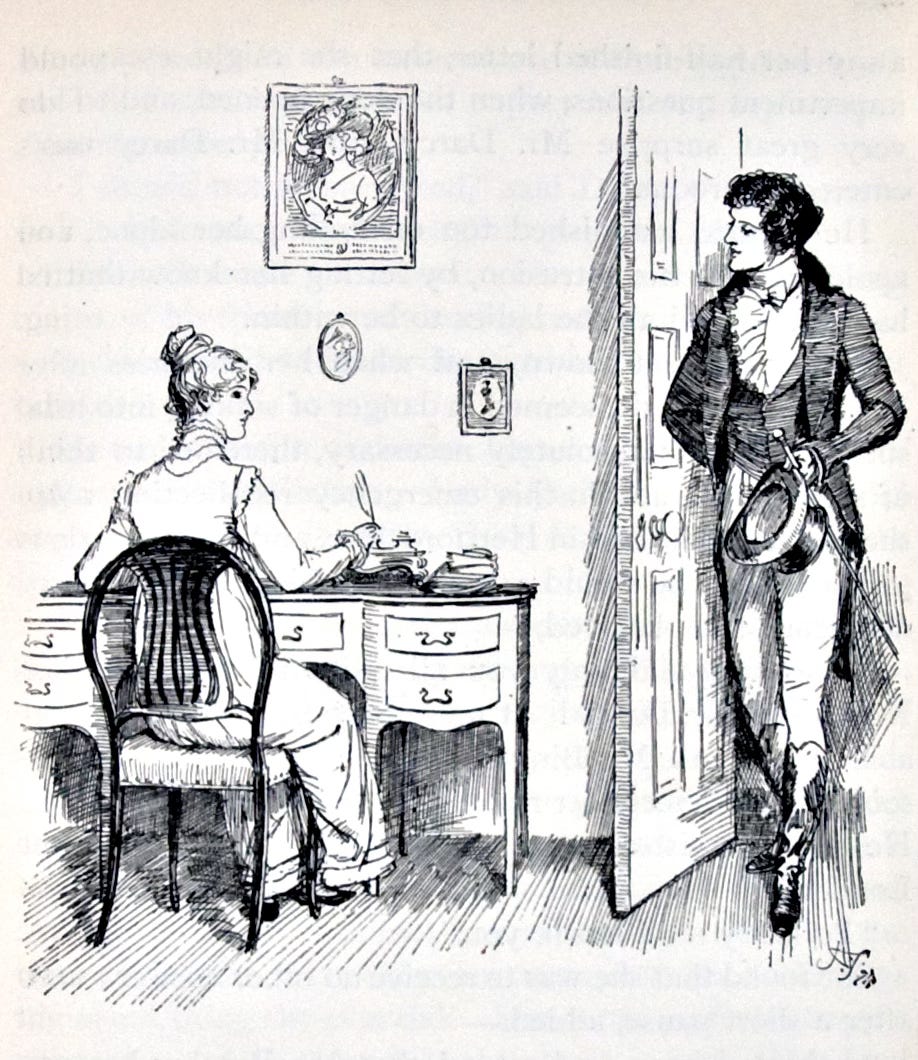

First Impressions was Jane Austen’s working title for the novel that became Pride and Prejudice, in which her leading man Fitzwilliam Darcy mounts an epic comeback after a shaky start and earns himself a place on the shortlist of greatest literary gentleman. He makes “It’s so over” into “We’re so back.”

This ascent is driven by six things he gets right, the Darcy Redemption Principles: 1) He confronts reality. 2) He reforms his character. 3) He maintains frame. 4) He draws strength from a home base. 5) He performs good deeds. 6) He says nothing about his good deeds. Those of us who have botched opportunities or made a dunce of ourselves at any point in the past might take note of how he returns from defeat.

Reality, Reform, Frame

It all starts with a rebuke. When Darcy asks for Elizabeth Bennet’s hand in marriage, the possibility of rejection hardly occurs to him—he is tall, dark, handsome, and rich, after all, and stations above her. So he’s taken aback at her No. Asked for an explanation, Elizabeth cites his “arrogance,” “conceit,” and “selfish disdain of the feelings of others,” and even calls Darcy “the last man in the world whom [she] could ever be prevailed on to marry.” Imagine hearing those words from the woman you loved, the woman you expected just moments ago to become your fiancée!

Elizabeth’s rebuke forces him to face the truth. All good things are born of a confrontation with the truth—and nothing good comes of delusion—but as TS Eliot once noted mankind can only bear so much reality. Lesser fellows might wrong in multiple ways when similarly rattled. They might dismiss the criticism altogether, call Elizabeth a bitch, and recommit to doing it their way. Or conversely they might be so wounded by her barbs that they lose themselves in the need for her affection and approval. But Darcy instead maintains enough composure to hear her words and see that he has been more than a little awkward in his disdain. He has flaws to fix. In the end, he confesses to Elizabeth, “You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous … You showed me how insufficient were all my pretensions to please a woman worthy of being pleased.”

At this point the Redpill Bros will object. They will insist on never changing just to please a woman—and they’re right! Changing just to please a woman is a guaranteed way to fail the test and lose her respect. A man consults his own judgment first—but he also owes it to himself to listen to those he respects (including the woman he loves) to determine whether the criticism is justified.

And Darcy, though he sees some justice, certainly does not accept Elizabeth’s word as law, particularly her mistaken complaints about his conduct toward Wickham and Bingley, which he pushes back against forcefully. Thanks to Darcy’s frame, Elizabeth even starts to recognize her own misjudgments on these matters. Most importantly, Darcy further distances himself from any suspicion of simpery by making zero efforts to show her—like a dog doing tricks on command—that he has reformed. He drops his pursuit and continues on with his life, as though he would never see Elizabeth Bennet again.

Home, Deeds, Self-Restraint

But of course that wasn’t the end of it.

When she finds herself roped into taking a tour of Darcy’s ancestral estate—on the assurance that he’s away—Elizabeth starts to wonder what could have been. To say that she falls in love with Darcy upon the sight of his spectacular property makes her sound like an inexcusable gold-digger—but there’s more to it. Even more than the grandeur of the place and the status it confers on the owner, Elizabeth is taken aback by the class and the taste apparent in every detail of the house, and the glowing praise with which the people there speak of Darcy. The house is an extension of the man.

Then Darcy unexpectedly arrives, and she is struck with the alteration in him—due in large part to the strength that comes from being in his element.

The bad news is that most of us won’t be heirs an aristocratic estate built up through generations of devotion to the family. The good news is that building a humble personal fortress which nevertheless exudes order and taste and cultivating a group of ride-or-die friends who make you stronger are within the realm of possibility—and to return to these after a setback will speed the recovery. Those who then see you in this new light might develop a very different second impression.

Darcy’s redemption hits a different level with the service he performs for the Bennet family in their hour of need. Elizabeth’s heedless sister Lydia has run off with the cad Wickham—foolishly thinking their fling will end in marriage instead of the ruin of her reputation. It will also ruin the prospects of her sisters. Who would want to marry into a family with scandal hanging over it? What other troubles await such poorly raised girls? To add to the bitterness: Wickham, who now threatens to destroy her family, is the same man whom Elizabeth upbraided Darcy for mistreating when she rejected his proposal!

Then Darcy goes to work. He hunts Wickham in the city, pays the man’s debts, secures him a commission in the army, and forces him to marry Lydia—thus securing the best life that a thoughtless girl could hope for. This Darcy takes to be his duty, since he failed to alert others to the man’s wickedness when he had the chance. (It’s hard to imagine a more gentlemanly fault than failing to smear the reputation of another.)

The best part is that he says nothing of it. Most of us, eager for a pat on the head, wouldn’t be able to keep the secret; we’d run and tell Elizabeth or arrange to have a messenger slyly pass along the information. The urge for credit is overwhelming. That’s not how Darcy does things, though. Had Lydia not mentioned his role in the wedding against his wishes, Elizabeth might never have learned what he’d done for her family.

Darcy’s conduct proves the point made by a wise man long ago—that those who humble themselves will be exalted. He refrains from trumpeting his good deed, and as a result he becomes an all-timer. Such hushed self-restraint shows that Darcy is guided by his own judgments; he saves Lydia not because he desires the family’s gratitude or Elizabeth’s favor, but simply because it was what he had to do. Upon discovering Darcy’s part in her sister’s wedding, Elizabeth is “in utter amazement” and “burning with curiosity”—descriptions Austen hardly needed to add, since the reader feels precisely those same emotions. We admire Darcy all the more because of the surprise and delight he makes possible in not telling.

Lesser Men and Larger Lessons

Austen accentuates Darcy’s redemption by contrasting his virtues with the failings of the lesser men around him: the cad Mr Wickham who loves to talk about himself in the hopes of manipulating others; the ironist Mr Bennet who fails to confront the disasters that his choices have wrought; the clown Mr Collins whose “self-importance and servility” makes personal dignity all but impossible.

This theme of second impressions is about more than just winning favor with others. The larger point is understanding how to move forward after a setback or disaster. Few tyrants are as severe as the past. It often inflicts scars and regrets upon a man, convinces him that these scars are who he is, and limits the possibilities before him. Darcy’s arc shows how a man might defy the limitations that the past yokes upon us.

https://thechivalryguild.substack.com/p/the-power-of-second-impressions