Ultra Processed Foods: Inflammatory and Addictive

To quote the timeless words of America’s 35th president, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, “There is nothing, I think, more unfortunate than to have soft, chubby, fat-looking children who go to watch their school play basketball every Saturday and regard that as their week’s exercise.”

Needless to say, if President Kennedy were alive today and stepped into a typical American fast-food establishment, he would be none too pleased with all the unfortunate, soft, chubby, fat-looking children he would be sure to see.

Perhaps he would think they are even more unfortunate than the ones he saw in his day. There are certainly a lot more of them now. (It’s hard to miss them.) Plus, at least those back in 1962 got their exercise from watching friends play basketball in something of a social setting, whereas today’s soft, chubby, fat-looking children get their exercise from watching strangers play video games on YouTube.

More recently, John F. Kennedy’s nephew, Bobby Kennedy, Jr., has expressed similar concerns about America’s soft, chubby, fat-looking children and the adults they grow into (pun intended). Back in August 2024, he noted, “One hundred and twenty years ago, when somebody was obese, they were sent to the circus.”

More importantly, Bobby Kennedy, Jr. is the face of the Make America Healthy Again movement. He also appears to be the driving force behind President Donald Trump’s efforts to remove a number of petroleum-based dyes from America’s food and establish a MAHA commission tasked with fighting childhood chronic disease. To date, one of the biggest moves by that commission has been the release of its “Make Our Children Healthy Again: Assessment,” often referred to as the “MAHA report.” The stated aim of the assessment is to examine the declining health of American children, along with the potential causes for this trend. A more detailed strategy for addressing the problem is said to be forthcoming.

Since its release, however, the MAHA report has been marred by allegations that it was written with the assistance of AI and that seven of the 522 sources cited in the report may have been fabricated. White House spokesperson Karoline Leavitt has since blamed this on a formatting issue. Whether the controversy was caused by an honest mistake involving buggy citation software, some 25-year-old staffer who decided to ChatGPT his way through it, or a leftover brainworm feeling a bit puckish, I don’t know. However, although inexcusable, whatever led to the controversy is rather unfortunate given that the controversy takes attention away from several otherwise valid and important points made in the report regarding the health of Americans.

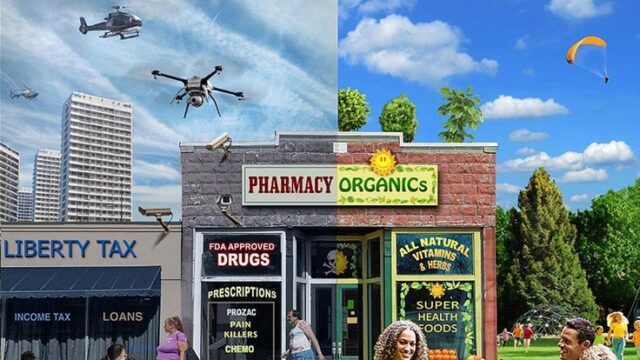

We’re overexposed to dangerous chemicals. The isolated, sedentary, screen-based lives we’re supposed to pretend are improvements over what we had even a decade or two ago are detrimental to both our physical and mental health. We’re over-medicated, partly as a consequence of our supposedly new and improved way of life. And, oh yeah, much of our food is poison – or at least contributing to a chronic disease epidemic if you want to be a little less dramatic.

With regard to this last one, the report specifically points a finger at something called ultra-processed foods, which are focused on here.

Industrial Formulations: It’s What’s for Dinner

Practically everyone has heard the term “processed food” at some point. Most, if pressed, could probably make some reasonable guesses about what is and isn’t a processed food, especially if presented with two clear options (e.g., a fresh grilled chicken breast and a chicken nugget). Most people even probably have some vague sense that the fresh grilled chicken breast is healthier than a chicken that has been transformed into a nugget. However, unless you were MAHA before it was cool, or a researcher focused on the relationship between our diet and disease, there is a good chance you are less familiar with just how harmful ultra-processed foods may be – or what the distinction even is between a processed food and an ultra-processed food.

To begin with, the question of what an ultra-processed food is, it is worth delving briefly into how the concept was developed. The concept of ultra-processed foods dates back to the late 2000s and became more widespread during the 2010s as researchers began discussing these foods in nutrition and public health commentaries critiquing the dominant dietary guidance at the time. According to critics, such guidance and guidelines were overly focused on explicit nutrient content and overly simplified food categories that were arguably meaningless at best or misleading at worst.

Diets high in folate and leafy greens were good. Diets high in saturated fat were bad. Full-fat milk was bad. Food categories were based largely on nutrient content, as well as a food’s plant or animal of origin. Whole grains were treated as no different than breakfast cereal. A fresh grilled chicken breast was no different than a chicken nugget. Processing was not something that was considered.

Critics, however, argued that processing was what actually mattered. There was a meaningful difference between fresh grilled chicken breast and a chicken nugget. Hence, they developed their own food classification system based on the degree to which food is processed.

According to this system, food can be categorized into four groups. Group One is comprised of natural, unprocessed, or minimally processed foods. These are the edible parts of plants, animals, fungi, and algae. Water is also included in this category. Some basic level of processing to make food safer, more edible, or last a little longer does not inherently preclude food from this category. Freezing a chicken post-mortem, then grilling it at a later date, does not make it any less of a chicken. No one has to kill their own chicken upon returning home from work.

Group Two foods are processed culinary ingredients often derived from Group One foods and used when preparing other Group One foods. Generally, these would not be eaten alone. Examples include oils, sugars, and butter.

Group Three foods are processed foods comprised of Group One foods to which a limited number of Group Two foods have been added for preservation or as part of preparation. Canned vegetables and canned fish fall into this category, as do some cheeses and freshly baked breads.

Lastly, there are Group Four foods, also known as ultra-processed foods, or UPFs. Critics and researchers of UPFs are generally reluctant to even refer to such items as food, instead opting for such terms as “industrial products” and “industrial formulations.” Often, such items are comprised of cheap ingredients derived from high-yield crops and animal remnants subjected to processes absent from the kind of preparation that could typically be carried out in one’s home or a standard restaurant kitchen. Additionally, they also may contain multiple Group Two ingredients and a plethora of additives. Such additives may help with preservation. Alternatively, they may serve solely cosmetic purposes to enhance appearance, smell, taste, or texture.

The end result is often a food-like item that is energy dense but nutrient poor, simultaneously possessing higher levels of both fats and sugars than what would normally be found in nature. Compared to Group One foods, UPFs also generally have less fiber, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Examples include sweet or salty packaged snacks, pizza, french fries, TV dinners, and reconstituted meat products. This is when your chicken nugget ceases to be a recognizable piece of chicken.

Notably, this system is considerably more complicated, if not complex, than older systems. Moreover, to some extent, the system is evolving (e.g., Groups Three and Four initially were less distinct). Certain boundaries may not always be clear. Certain nuances may at times be lost.

If one grows lettuce, tomatoes, and cucumbers in a backyard garden, then drowns them in ranch dressing, does that salad of Group One foods automatically become a Group Four food, or is it a collection of Group One foods eaten with a Group Four food? Is the concept of a “healthy” can of vegetable soup an oxymoron? Are all TV dinners equally bad? Are cookies baked at home any better than a pack of Oreos? Is a freshly-baked pastry from your local coffee shop just as bad as a Twinkie? (I mean, at least the freshly-baked pastry can die – unlike the Twinkie, which is said to be immortal).

When reading through the published scientific literature on UPFs, the answers to these kinds of questions are not always clear or obviously agreed upon. Sometimes, even when they are, the reasoning is not well-articulated. Strictly speaking, pasteurized milk is still a Group One food while a bottle of Perrier, because it is carbonated, is a Group Four food. But does that make the bottle of Perrier less healthy than the milk?

However, maybe fixating on such fine details misses the point. As one researcher in this area indicated about a year ago when she gave a talk at my university, a good rule of thumb for determining whether something is a UPF is if could you reasonably be able to reproduce it in your own kitchen from ingredients you can purchase at a standard grocery store (assuming you have some level of culinary skill and a working kitchen). Although some nuance may get lost, the proposed rule of thumb does get to the point.

Yet, distinctions between the different categories of UPFs aside, perhaps the more important question for a lot of people is how bad UPFs actually can be. In other words, what’s the harm? From the list of examples provided previously, the obvious concern would be that consuming too many UPFs would produce the kind of soft, chubby, fat-looking child that would make John F. Kennedy cry and his nephew send them to the circus upon reaching adulthood. However, the fact of the matter is that the harms are much larger than that (pun intended).

Ultra-Processed Foods: They’re Grrrreatly Inflammatory

As I wrote in an article for Brownstone Journal about a year ago, there are a number of health problems associated with what has been dubbed the “Western diet.” Disturbances to the composition of microbial community in one’s gut, the deterioration of intestinal barriers, and increased inflammatory processes, both in the gut and the rest of one’s body, are among the greatest concerns here. One likely source for these problems is the composition of the Western diet itself, which generally is described as high in energy, sugar, salt, and animal fats and proteins, but low in fiber from fruits and vegetables. Another likely source is the presence of the kinds of additives discussed in the MAHA report.

On a broad level, many additives commonly found in UPFs like artificial preservatives, colorants, emulsifiers, and sweeteners, have been linked to perturbations of gut microbial communities, the erosion of one’s intestinal lining, and inflammation.

For example, colorants such as Red 40 and Yellow 6 have been shown to trigger inflammatory bowel disease-like colitis in genetically susceptible mice. Aluminum has been associated with chronic inflammation and granuloma formation. Emulsifiers are believed to disturb microbial gut communities in a manner that increases the prevalence of bacteria that trigger inflammatory processes that contribute to colitis and metabolic disease. Experiments using rodent models suggest fructose exposure also perturbs gut communities, as well as induces the death of cells in the intestinal barrier leading to its deterioration and the entry of bacterial endotoxins into one’s bloodstream, where they can damage organs like the liver.

Without going through each remaining additive, the general pattern here should be clear. Many additives are harmful to your health. Moreover, if you consume multiple additives as a routine part of your diet, it is likely the net effect is not good. Making matters worse, the inflammatory properties of the additives contained in UPFs may not even be their worst quality as many of the foods to which they’re added appear to be highly addictive.

Once You Start, You Just Can’t Stop

A growing body of research on UPFs suggests that the consumption of such foods likely rewires the brain in much the same way as addictive drugs, thus giving new meaning to some now seemingly ill-advised marketing slogans. Needless to say, the research in this area leans heavily on earlier work on addiction and learning (i.e., Pavlov’s dogs and Skinner’s rats).

To better understand how food can become addictive, one must first look at how food processing influences the availability of the nutrients you can obtain from a particular food, the neurophysiological processes that regulate your motivation to eat, and how nutrient availability can affect these regulatory processes.

To start, when you consume food, your body breaks down that food into nutrients that can then pass through your gastrointestinal tract and into your bloodstream, which then transports those nutrients to different organs around your body. Cooking, along with other basic processing techniques such as boiling, baking, and crushing, can increase the availability of these nutrients and thus how quickly they can reach different organs. Simply put, there are more available calories in a cooked sweet potato than in a raw sweet potato or a cooked piece of meat compared to a raw piece of meat.

Neurophysiologically, nutrients and other stimuli in the gut trigger signals that ultimately reach the brain to influence feeding behavior. More specifically, a part of the brain referred to as the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (the hypothalamus being a part of the brain involved in many basic behaviors related to survival) contains two sets of neurons that play important roles in the regulation of feeding behavior. One group, agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons, is activated by hunger and fasting and can prompt mammals to search for and consume food. The other group contains proopiomelanocortin neurons that are activated by positive energy balance and encourage fasting.

Under experimental conditions, when different nutrients such as lipids and glucose are infused directly into the gut, AgRP neuron activity is inhibited, leading to a decrease in food consumption. Where this ties into addiction is that the hypothalamus shares a number of interconnections with the brain’s reward system and hence the various structures (e.g., the striatum and ventral tegmental area), circuits (e.g., the mesocorticolimbic circuit), and neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine) involved in learning and addiction. This is also the system that drugs of abuse are said to hijack.

Over the course of evolutionary history, this reward system and all it entails likely developed to help mediate associative learning as it relates to biologically relevant behaviors such as reproduction and the consumption of food. With regard to food, this system appears to be influenced by both an organism’s explicit sensory response to food, as well as by signaling in the gut triggered by a food’s nutritional contents. As these two signaling processes are paired, the sensory experience of consuming a particular food becomes linked to its nutritional value. Subsequently, an organism comes to experience sensations of pleasure when consuming that food (or similar foods) and becomes motivated to seek out such foods in the future.

These kinds of associations are obviously important for an organism’s survival. Being motivated to eat things that provide nutrients can be beneficial for not dying of malnutrition. However, the development of these associations and subsequent behaviors can be influenced by a number of variables that can maladaptively affect food preferences and an organism’s motivation to eat, sometimes leading to a suite of behaviors and neurophysiological alterations akin to what one might see in addiction.

On a very basic level, simple food preparation can influence food preference. For example, under experimental conditions, rodents will come to prefer cooked sweet potatoes to raw sweet potatoes. Likewise, more complex food processing can influence a person’s ability to control how much they eat, as well as the desirability and perceived value of a food item.

Research involving human participants shows self-reported behaviors indicative of addictive eating (e.g., a perceived loss of control over how much of a food one eats) tend to be more associated with foods that are high in both fat and sugar, a characteristic of many UPFs (e.g., pizza, ice cream, milk chocolate), than foods that are high in either fat (e.g., salmon) or sugar (e.g., bananas). In an experiment involving a quasi-artificial bidding task, people similarly showed a preference for such foods in terms of their bidding activity. When snacks possessing this combination are incorporated into the diets of healthy participants, these individuals come to report a decreased desire for low sugar snacks and a decreased preference for low fat (and also very high fat) snacks.

Research using an fMRI has shown that the regular consumption of such snacks increases activity in several parts of the brain, including parts relevant to learning and addiction, when participants are presented with cues meant to predict the delivery of a high-fat-high-sugar snack and when they are consuming such a snack. Borrowing even more from the frameworks used to understand addiction, some researchers have suggested that the concentration of sugar and the speed with which sugar from a food is absorbed into the bloodstream can also influence the food’s potential for addiction. (In addiction terms, an addictive substance injected directly into one’s blood would have a greater potential for addiction than if swallowed in a time-release capsule).

Commentaries and opinion pieces in peer-reviewed journals take the comparison between UPFs and drugs of abuse even further, emphasizing how UPFs meet the scientific criteria for addictive substances put forth by the US Surgeon General in 1988 when cracking down on cigarettes. Namely, these pieces argue that UPFs cause compulsive use, alter one’s mood through effects on the brain, are reinforcing in Pavlovian and Skinnerian terms, and trigger cravings.

They also highlight that if a similarly harmful and addictive substance were to be introduced into our society today, we likely never would allow it to become available to the general public, especially not to children.

The Cornucopia of Mostly Bad Solutions

Because of their addictive nature, and the other harms they do, the stated or implied conclusion to which most UPF researchers arrive is that UPFs should be regulated in much the same way as tobacco products.

Needless to say, many of those who do this research tend to come off as do-gooders, would-be-social engineers who wholeheartedly embrace the idea of governments working with experts like them to micromanage every aspect of the food industry along with the personal diets of individuals and their families through the standard array of regulations, taxes, incentives, and nudges. Among the proposed suggestions for waging war on UPFs are greater taxation of the ingredients used in UPFs and the final products, a ban on advertising for UPFs, and a prohibition on the sale of UPFs within convenient walking distance of schools.

For those who are more libertarian-leaning, these kinds of solutions likely seem like government overreach and come off as undesirable. So should more technocratic solutions that embrace health surveillance devices that at best encourage Americans to hand over vast amounts of personal information to corporations (and possibly the government) in exchange for questionable benefits to their individual health. (RFK, Jr. himself seemed to come out in favor of something along these lines at a Congressional hearing, although, in fairness, he later made some clarifications). Back in March, Robert Malone wrote a piece regarding some of the practical and philosophical issues the MAHA movement faces here as they work to define the “acceptable limits” of the government’s role in their health.

However, whether one agrees with these kinds of solutions or not, their possible undesirability should not diminish the scientific merit of much of the research done in this area. Also, if one does not support the nanny-statist and/or technocratic approaches to UPFs, that leaves the lingering question of what, if anything, should be done about them.

To start, not all the ideas put forth by the experts are inherently bad. Better education about diet, nutrition, and the preparation of healthy meals through science, nutrition, and home economics classes in K-12 is a fairly reasonable idea that most people should be able to support. Encouraging exercise and fitness (and I would add putting an end to the embrace of obesity as an alternative lifestyle to be celebrated) would also be a good step in the right direction.

Removing UPFs from the menus of public schools, and possibly those of prisons and hospitals, probably aren’t the worst ideas either (although when dealing with populations of free adults, providing healthy choices would be the fairer option).

And, although bans on certain additives as Trump has ordered does have my small “l” libertarian senses tingling with apprehension, I cannot say I am losing much sleep over the government removing likely poisons from my food, especially if they only serve superficial roles.

However, beyond a relatively small handful of basic, commonsense measures that don’t cross the line into nanny-statism, it likely is best to diverge from the experts. At some point, individuals are responsible for what they put into their bodies and the bodies of their children. This is something that should remain true even if some would have made the president shed a tear in 1962 or would have been sent to the circus 120 years ago.

https://brownstone.org/articles/ultra-processed-foods-inflammatory-and-addictive/