What We Find So Difficult to Admit

What we find so difficult to admit is that our quality of life isn’t getting better and life is not getting easier. When presented with tangible evidence of this, we seek examples that “prove” life is getting better, because if we admit the quality of our lives is not improving, then our core faith–that Progress is permanent because we’re innovative and technology always advances–is false.

And if this belief is false, then our faith that everything will get better “no matter what” crumbles.

So when presented with evidence that things are not getting easier and better, we hold up a scientific or medical discovery, or rearview cameras on vehicles, or the wonders of the Internet–all human knowledge at our fingertips–as evidence life is getting better and progress is intact.

But the quality of life isn’t the sum of new medications or technologies; it’s the sum of the durability of products, the affordability of the essentials of a high-quality life, the relative absence of precarity and unfairness in everyday life, the totality of our physical and metal health, and the ease of navigating the systems that underpin the everyday quality of life.

When presented with evidence of the decay of our quality of life, we revert to digging up outliers as “proof” that in some remote pockets of the nation, housing is still affordable, conveniently overlooking the most consequential point of any comparison, which is: what was attainable without extraordinary sacrifice and effort to the average household in the past compared to now?

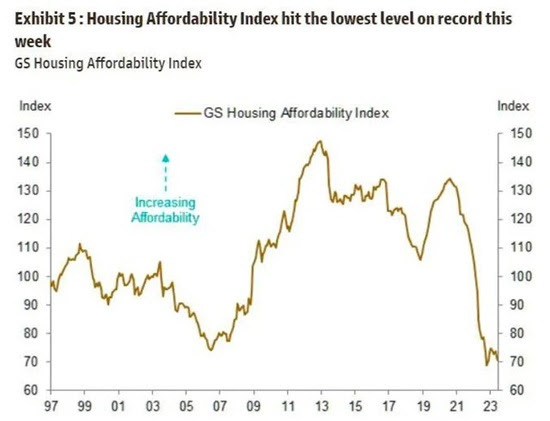

So when I observe that where it took about three times median household income to buy an average house in 1985 ($25,000 in household income, $75,000 home price) and now it takes 10 times income in many urban locales ($80,000 household income, $800,000 home price) or 6 times income for average homes elsewhere, I get this response: well, if you rent a cubbyhole in someone else’s apartment and live like a monk for five years, you can still save up the down payment for a house outside desirable neighborhoods.

In other words, since it’s still possible with extreme sacrifices and extraordinary effort to buy a house, “Progress” and “affordability” are still intact.

My partner and I built dozens of houses in the mid-1980s, from modest starter houses on up. We could still build a basic house for around $40 per square foot. The cost now is 10-times higher, about $400 per square foot.

Official inflation is $1 in 1985 is worth $3 today. So adjusted for inflation, construction costs are 3 times higher than they were 40 years ago: 3X $40/sq. ft is $120, so $400/sq, ft. is more than 3 times what the cost should be adjusted for inflation.

The income-to-home-price ratio is 2 or 3 times higher now–not 3X income, 6 to 10X income– and we can still claim housing is “affordable”? Compared to what? Certainly not the past metrics of affordability.

This absurd “everything’s still fine” claim is “proof” not of affordability of housing but of our extreme resistance to admitting the truth: that housing was far more affordable in the past and so we’ve regressed: affordability has decayed or collapsed, depending on our willingness to be blunt, as opposed to adroitly arranging a fig leaf.

Then there’s the unfairness built into this decay / collapse. A +65 year old homeowner noted that his property tax in high-property-tax California was $2,800 annually, a fifth of what a young household pays for the house next door, due to Prop 13 limits on increases in property taxes. This staggering advantage can then be transferred, a privilege unavailable to the new homeowners next door paying 5 times more in property tax.

I notice a startling increase in expletive-laced posts online complaining about the shadow-work of constantly having to provide endless security codes to access online accounts. Now we’re told that passkeys are the new technological workaround to the shadow-work of trying to maintain security.

But this is artifice, for the entire digital realm is insecure Swiss-cheese: AI chatbots and systems are Swiss-cheese, the Internet is Swiss-cheese, corporate databases are Swiss-cheese, and now, AI is enabling an expansion of malware and malicious software unrivaled in the digital age: AI tools generate hard-to-detect hacking programs, deep-fakes, ransomware–the list is endless, and this is only the very early stage of an explosion of security-breaking advances.

Google Gemini Flaw Turns Calendar Invites Into Attack Vector.

VoidLink Linux Malware Framework Built with AI Assistance.

Craig Jones warn AI is accelerating complex malware, while dark web tools like Nytheon AI make advanced cybercrime more accessible globally.

AI Deepfakes Are impersonating Pastors to Try to Scam Their Congregations.

Digital security is far from the only issue raised by AI’s negative cultural-economic influence:

AI-generated livestreams are selling products using synthetic video and voice.

Lamar wants to have children with his girlfriend. The problem? She’s entirely AI.

As for technology, I also see expletive-laced diatribes on the low quality of current software. As someone who bought an original Macintosh PC in 1985 and has used Windows since the late 1990s, it’s undeniable that Windows 2000 Professional was stable and adequate for any task. Twenty-five years later, the Windows OS is inarguably bloated and gains in utility–if any–are negligible given 25 years of constant costly “upgrades.”

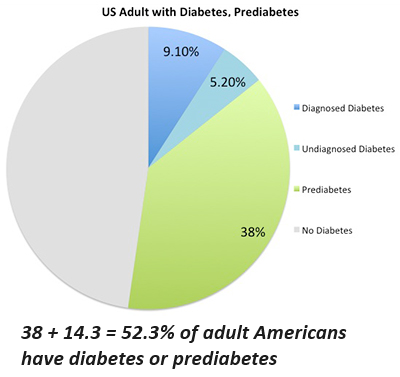

As for health, the advent of GLP weight-loss medications is constantly hyped as “miraculous,” hype that conveniently ignores the high cost of these meds, the fact they must be taken for life, their often-horrible side effects, the fact they don’t work for everyone, and so on.

What few (if any) ask, is why did we not need GLP medications in 1985? The reason is the majority of people were average weight and so there was no pandemic of weight-related chronic diseases. That the astonishing increases in “lifestyle” diseases were caused by the decay of our lifestyles–or collapse, if we’re blunt–cannot be conceded, because we cannot bear to admit that Progress is contingent and can regress and decay, or even collapse.

In 1985, people didn’t have to cling on to jobs because healthcare was unaffordable once they quit that job. Coverage claims weren’t routinely denied. There weren’t chronic shortages of physicians.

It’s not difficult to find videos of people complaining about skyrocketing vehicle repair bills, skyrocketing utility bills, skyrocketing insurance costs, and so on. All this is brushed aside with references to official inflation, which has been gamed to appear near-zero: 2.5%. That this statistic doesn’t reflect the impact of higher costs on the quality of life is conveniently ignored.

And so we play this game of highlighting the shrinking pockets of vitality, affordability, quality and security, as if a pocket of urban vitality in a rising sea of empty storefronts proves anything, as if housing that’s still affordable in a remote township with little economic opportunity proves anything, as if an expensive, unrepairable modern vehicle prone to digital malfunctions is “more reliable” than my 1998 Civic (good luck with that “more reliable” vehicle lasting 27 years with minimal repair costs) proves anything, as if a medication that must be taken for life that doesn’t replace healthy diets of real food and fitness proves anything.

Consider a basic kitchen appliance, a blender. Our Model 403 Oster blender, around 65 years old, manufactured in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, still works just fine. We also have a recent model blender, assembled outside the US. The case is plastic, as is the pitcher, where the 403 (and later models manufactured before globalization and the degradation of quality to increase profits) had steel cases and glass pitchers.

Shall we play the game of finding outliers of products and services that are demonstrably higher quality and exhibiting greater durability than those made pre-globalization and the degradation of quality to increase profits? How about documenting the collapse in quality from around 2010, on, when globalization and cartels became dominant economic forces?

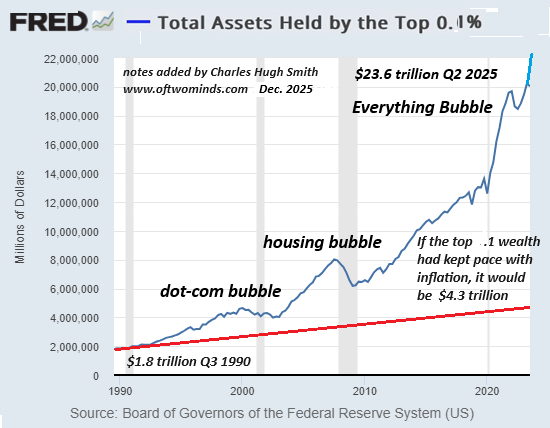

All these games prove is our tremendous resistance to admitting life is more difficult now, not easier, as risks and costs have been offloaded from corporations and institutions onto households, artifice and expediencies have replaced real solutions, our economy became dependent on debt, credit-asset bubbles and the inherent inequalities built into “the wealth effect,” an economy now dominated by extractive, exploitive monopolies and cartels that buy political influence with pocket-change in our corrupt auction of financial favors?

Can we dispense with outliers as “proof” all is still well–households earning 4 times median incomes, houses selling for a few thousand dollars, and all the other risible “proofs”?

Or perhaps we’ll admit the issue isn’t just the visible decline in the quality of life; the issue is our resistance to facing this decay, for if we can’t bear to face the erosion in our quality of life squarely, we’re never going to actually advance any real solutions.

https://charleshughsmith.substack.com/p/what-we-find-so-difficult-to-admit