Why the World is Crazy

The world is crazy because the gap between the pat solutions we embrace and the scale of resources required to manifest those solutions is wildly asymmetric. There are other sources of craziness, of course–here’s my list of 20–but the asymmetry between the pat solutions and the scale of what it actually takes to make all this happen is the core source of craziness.

Large numbers are abstractions because we can’t visualize their scale or context. For example, it was recently announced that Venezuela agreed to deliver 50 million barrels of oil to the US. This sounds like an impressive number until we learn that the US consumes 20 million barrels a day. So 50 million barrels is 2.5 days of America’s consumption–decidedly less impressive.

The federal deficit in 2025–money that was borrowed to fund federal spending–was $1.8 trillion. $7 trillion was spent and revenues totaled $5.2 trillion. So roughly 25% of federal spending was borrowed. Fifty years ago in 1976, the nation’s entire GDP was $1.8 trillion.

It’s difficult to make sense of these large numbers without a solid grounding of the scale and context, and this is what’s obscured in pat solutions. For example, 20 years ago converting switch grass into biofuels was touted as an environmentally sound solution to substitute biofuels for oil. But like all such pat solutions, this “solution” wasn’t scalable: making a few barrels of switch-grass sourced biofuels didn’t mean that the process could be scaled to production that actually moved the needle of oil consumption.

Consider the promoters of pat solutions. They are never people who have actually managed the construction of a nuclear power plant. They are pundits or economists who read a press release and are delighted to announce that modular nuclear power plants will be churned out like lawnmowers, and electricity will be practically free. Problem solved: next.

What’s left off camera is all the hard parts of this vast undertaking–the open-pit mines, the endless line of rail cars hauling ore to be ground up, the diesel-powered machines loading the ore, the smelting / production of cement and steel, not to mention the vast expense and toil required to refine uranium or thorium fuel.

Like the robot that appears to be autonomous on camera but is actually being controlled by a human operator, all the hard parts–and the daunting scale of the “solution”–are always left off-camera.

Item 6 on my list of the 20 dynamics shaping the future raised some questions from readers: Scale and asymmetry are the core contradictory dynamics.

The contradiction is the tremendous asymmetry between the vast scale required to expand “Progress” (defined as continuing growth of consumption and technology) and our understanding of the enormity of this scale when measured in resources, capital and risk.

Pat solutions are never presented as requiring tradeoffs or creating risk: innovation and ingenuity guarantee success, and there will always be more than enough money to fund both today’s consumption and invest trillions of dollars in resource and capital-intensive solutions for the future.

This context allows us to think the “problem” is “money” rather than the vast asymmetries of scale, cost and risk that are part and parcel of any prodigious enterprise. The cost may be measured in “money” but the true tangible cost is measured in the energy and resources required to construct the solution.

The intangible costs include the opportunity costs–what more productive use of the capital and resources was passed over–and the multiple risks of failure: either the solution doesn’t actually work reliably enough to scale up, or it’s economically unviable due to its cost exceeding the market value of its output.

The third risk is that the solution is only economically viable in its first installation, as the future replacements / recycling of all the worn-out stuff is not viable / do-able no matter how much “money” is thrown at it.

Consider the pat solution that solid-state batteries will enable the electrification of virtually everything, starting with the 1.5 billion light-duty vehicles on Earth (autos, SUVs, etc.) and then moving on to heating, cooling, industrial production, AI data centers and so on.

So what quantity of resources and energy are required to fabricate 1.5 billion large batteries for vehicles, and the addition billions of batteries envisioned for the rest of the electrification project? Is it possible to recycle these billions of complex batteries when they’ve reached the end of their utility? If so, at what cost? Who will pay these costs–the producers, or the consumers, or …?

How many resources will be needed to make a replacement set of billions of batteries in a decade?

We recoil at these questions because we want to believe the pat solutions will all work without us having to sacrifice or risk anything, as the prospect of tradeoffs, sacrifices and risks unsettle us.

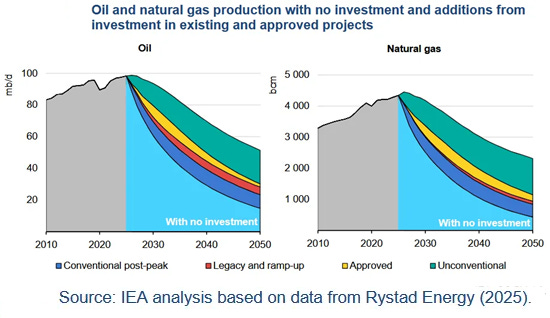

Let’s review some basic charts of energy, the resource that enables the extraction of all other resources.

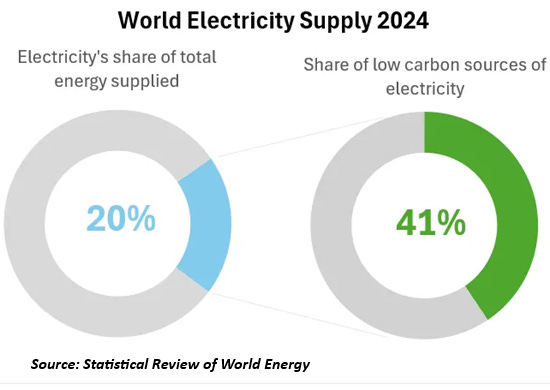

Electricity is 20% of the total energy we consume. So converting all electricity production to non-oil “sustainable” sources still leaves 80% of our consumption to be powered by oil or oil substitutes.

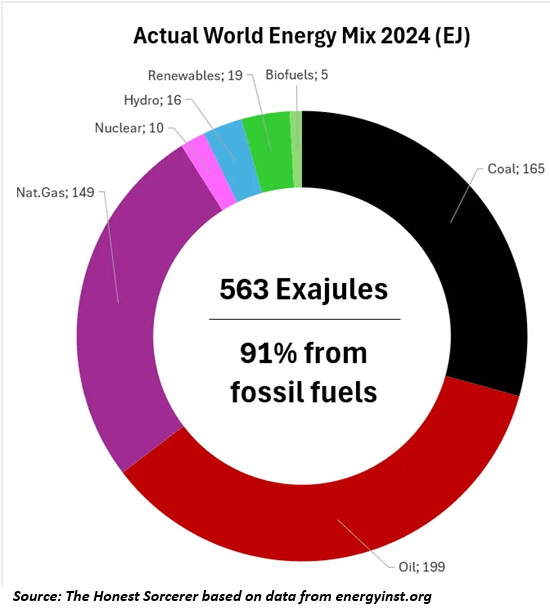

Depending on the source doing the calculations, between 86% and 91% of all energy consumed today is hydrocarbons. Due to Jevon’s Paradox, all the energy generation we’ve added in wind, solar, etc. has simply added to our consumption. It hasn’t replaced hydrocarbons to any meaningful degree.

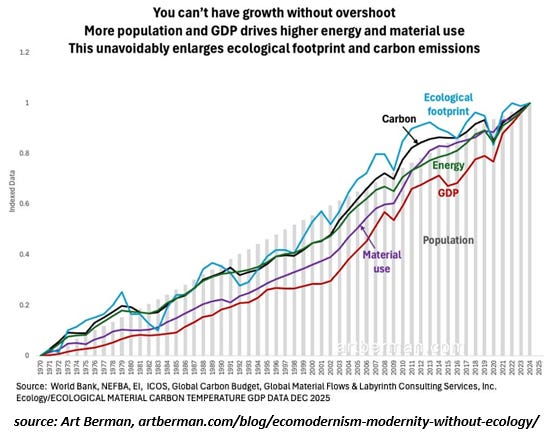

Since “Progress” is defined as “growth,” then we must consume more of everything, despite all the hoopla about the pat solutions:

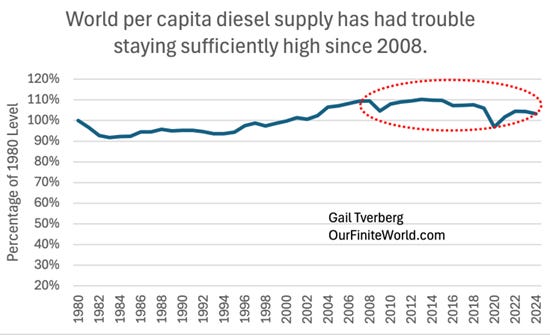

The essential fuel for industry is diesel, and the world has been unable to “grow” diesel production despite enormous sums being invested in new technologies and extraction of oil-oil equivalents.

Without massive investments of capital and resources, production of hydrocarbons cannot be sustained. The miracle of fracking tight oil production is running into limits of depletion, environmental consequences and costs.

America’s Biggest Oil Field Is Turning Into a Pressure Cooker: Drillers’ injection of wastewater is creating mayhem across the Permian Basin, raising concern about the future of fossil-fuel production there.

Shale drillers have turned the biggest oil field in the U.S. into a pressure cooker that is literally bursting at the seams.

Producers in the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico extract roughly half of the U.S.’s crude. They also produce copious amounts of toxic, salty water, which they pump back into the ground. Now, some of the reservoirs that collect the fluids are overflowing—and the producers keep injecting more.

It is creating a huge mess.” (wsj.com)

Once again, all the practicalities of pat solutions that fulfil our vision of Progress–”growth” and “technology”–are off-camera. This is why the world is crazy–and unprepared for the inevitable failure of pat solutions.

The real solution is a new understanding of Progress that is focused on doing more with less and quality of life, a new definition / goal that measures “progress” by these standards rather than solely by growth, technology and profits this quarter.

OK, so what’s actionable for me in all this?

We can start with realizing that all the pat solutions are designed to sooth our anxieties and boost our confidence that “Progress” is both inevitable and painless: bio-jet fuel will replace petroleum jet fuel, electric aircraft are the solution–so no worries.

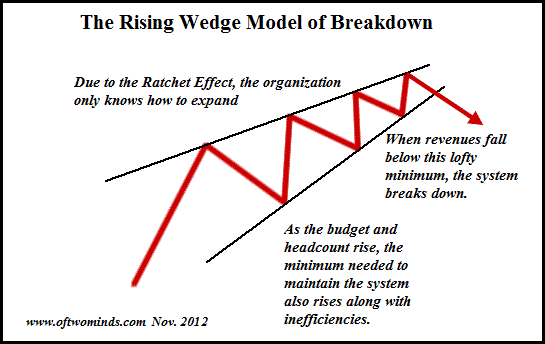

We can also balance the belief that everything will continue running as-is for decades with the possibility that many of the systems we depend on may be vulnerable to modest decreases in resources and funding–what I call the Rising Wedge Model of collapse.

I’ve addressed this numerous times over the years, and the basic idea is institutions / systems have been optimized for expansion, and so they lack the capacity to contract without breaking. There is no institutional experience of reductions in resources, and those who chose to join the institutions are selected (and self-selected) to manage complex processes and bureaucracies, not reinvent systems to be less complex on the fly.

One analogy is a household budget. If there are high fixed costs and little surplus in the budget, then there is no way spending can be cut by 10% should income fall 10%. Some essential expense will go unpaid, and the question is where the default will fall. Credit cards can be maxed out as a temporary fix, but that only increases the monthly expenses as interest eats borrowers alive once income declines.

Sooner rather than later, major changes of the undesirable sort become inevitable.

What’s actionable is to see through the artifice of pat solutions and harden our household against the possibility–however slight it appears at the moment–that various systems may no longer function should resources become unaffordable to the majority and modest constraints start breaking over-optimized, overly complex, inflexible institutions.

I call this process thinking through Plan B (a reduction in income and/or a rise in expenses, job loss, etc.) and Plan C (systems start unraveling / ceasing to function reliably at costs the majority can afford). If everything continues on as-is for decades to come, then the planning gathers dust. No harm, no foul.

The less we owe in debt and the more we own and control, the lower our fixed costs and our exposure to risks we don’t control, the greater our self-reliance.

The “what if” planning is free, and plotting a new course doesn’t require major sacrifices or decisions. Adjusting the rudder (or trim tabs) slightly now may well steer the ship clear of the iceberg.

https://charleshughsmith.substack.com/p/why-the-world-is-crazy