Why We Fight (Why I Fight)

A chance encounter in a Taco Bell parking lot helped revive my spirit by reminding me what my priorities are.

Shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, the famous Hollywood Director, Frank Capra (“Mr. Smith Goes to Hollywood”, “It’s a Wonderful Life”) enlisted in the Army, like so many others of his generation, to fulfil his patriotic duty to defend his country. Amazingly, the US military saw fit to put a round peg into a round hole, and Capra was not shipped off to the infantry, but rather put in charge of producing perhaps the most essential propaganda of the Second World War, a seven-film series entitled “Why We Fight.”

These films were deemed to be essential to the American war effort by the Chief of Staff of the US Army, General George C. Marshall, and by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who ordered the series to be released for viewing by the American public.

The films were also shown to the millions of Americans who put on the uniform of the United States military who were to be sent off to fight, and possibly die, in a foreign land. America was coming off the decade of the Great Depression, and most Americans were inwardly looking, seeking to resolve their own problems at home, and not inclined to foreign intervention. Isolationism was a prevailing sentiment, one that President Roosevelt had to constantly maneuver around as he sought to provide aid to nations like Great Britain and the Soviet Union as they fought Nazi Germany. Some 16.1 million Americans served in the military during World War Two (12% of the population.) Of these, 39% volunteered, while the remaining 61% were drafted. The “Why We Fight” film series was deemed critical in getting the minds of the majority of American soldiers who didn’t volunteer to serve to break free of their isolationist tendencies and become part of the “Greatest Generation” of Americans who went off to war to liberate Europe from the Nazi boot and punish Imperial Japan for the perfidy of Pearl Harbor.

I am of a certain age, where my childhood was marked by the kind of Capra-esque patriotism defined by the “Why We Fight” film series. Television signed off at midnight by playing the “Star Spangled Banner”, and would sign back on at 6 am playing the same. I grew up during the height of the Cold War, and lived in the era where the National Anthem was played in theaters before the start of every movie (the US Congress passed a law in 1952 mandating this in order to reinforce American values and counter the perceived threat of communism.)

And we stood up when the anthem was played.

And we placed our hands over our hearts.

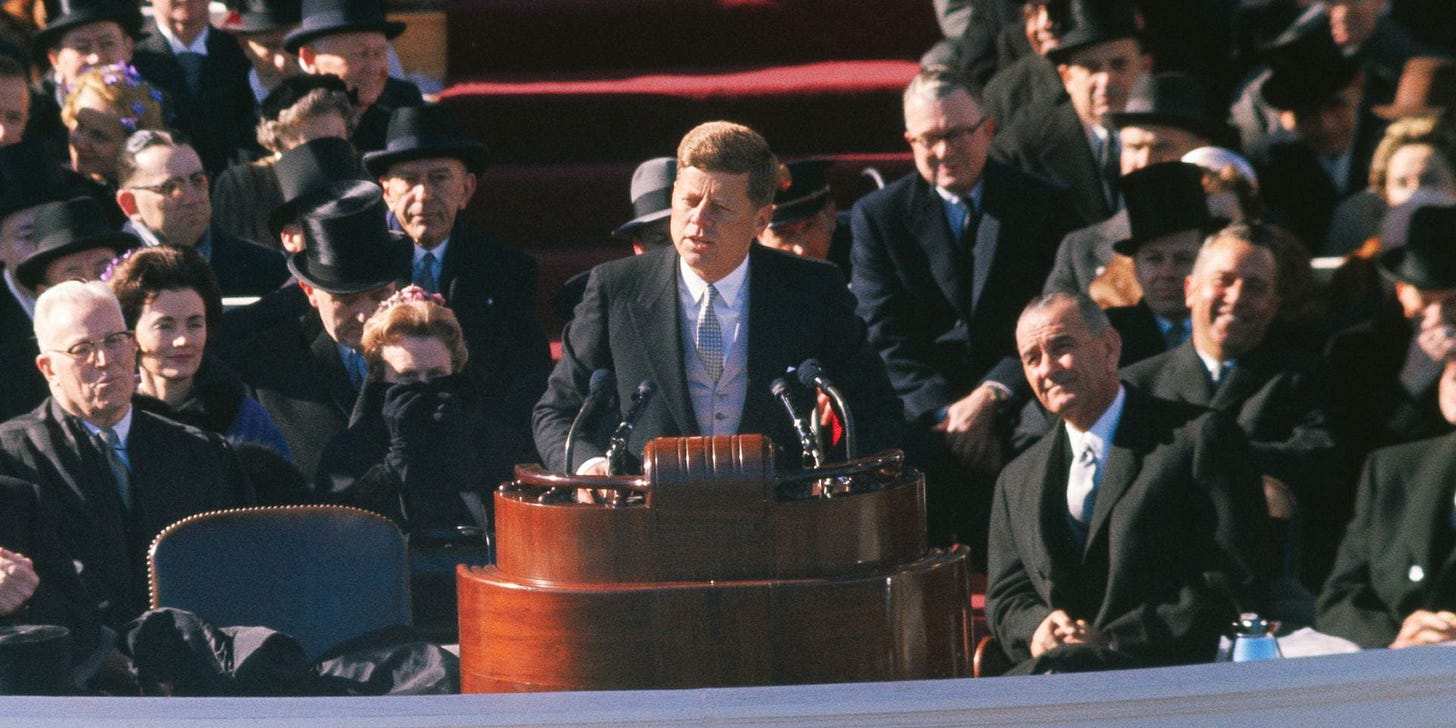

I grew up with two images staring down at me from the walls of my bedroom—one, a poster of John F. Kennedy with a quote from his Inaugural Address of January 20, 1961 (some six months prior to my birth):

“Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.”

My father was a career Air Force officer, and my mother had served as an Air Force nurse before being medically discharged.

The concept of service to the nation permeated everything we did as a family.

Later I was able to read the whole inaugural address, and it struck me that as important as those words were, the context in which they were presented was equally, if not more, important:

In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility — I welcome it.

I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it — and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Thus, the context of the words that I woke up to every morning wasn’t simply the concept of service itself, but rather service in the defense of freedom in its hour of maximum danger.

And the context wasn’t simply service to my nation, but service to all mankind.

“The way that we talk to our children becomes their inner voice.”

This is the mantra of child psychologists, a reality which permeates everything about childhood and who we become as adults.

I was literally conditioned from childhood to serve my country and all of humanity.

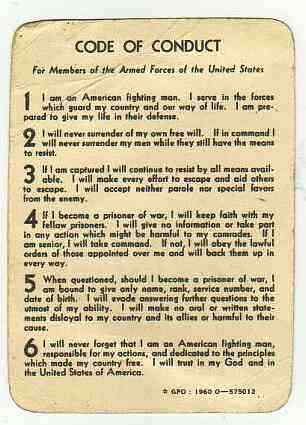

The other poster was the Code of Conduct for Members of the US Armed Forces, with the first paragraph presented in larger bold text in order to stand out:

I am an American fighting man. I serve in the forces which guard my country and our way of life. I am prepared to give my life in their defense.

During my childhood, my father deployed to Turkey as part of a NATO nuclear reaction force, where F-100 Super Sabre aircraft stood strip alert duty with nuclear bombs loaded under their belly.

He spent a year in Vietnam with the 10th Air Commando Squadron (the Skoshi Tigers), proving the combat effectiveness of the F-5 fighter.

He deployed to South Korea in the aftermath of the USS Pueblo incident.

He helped oversee the “Vietnamization” of the South Vietnamese Air Force in the aftermath of the US withdrawal from South Vietnam.

He was central to the bringing on line a CH-53 helicopter which played a critical role in the evacuation of US Marines from Koh Tang Island in 1975, potentially saving dozens of lives.

He advised the Turkish Air Force during the height of the Cold War.

He served on the front lines of the Cold War in West Germany, part of a US contingent of forces deployed to defend NATO from the Soviet Union.

For twenty years, from 1964 to 1984, my entire life was wrapped up in the service my father performed to his country.

And because of the example he set for me, as soon as I graduated from High School, at the age of 17, I enlisted in the United States Army.

To serve my country.

I later transitioned to the Marines, where I was commissioned as an officer.

The rest is history—29 Palms, Votkinsk, Desert Storm, and Iraq.

These are the events and places that shaped my adult life, all built on the foundation of my childhood experiences which defined not just the notion of service to country and humanity, but the duty as a citizen to perform such service.

For me, it was never a question of choice, but a matter of duty, of obligation.

Even today, this is what drives me—the duty and obligation of service to my country and to all of humanity.

As John F. Kennedy requested of me and my fellow Americans on that fateful day in January 1961.

This is why I fight.

This is why I broke my back trying to prevent a war with Iraq premised on lies I was empowered to disprove.

This is why I spoke out against the efforts to portray Iran as a nation seeking to acquire a nuclear weapon.

This is why I have fought against the disease of Russophobia

And the Genocide of Israel.

And the scourge of nuclear weapons.

This is why I openly advocate for arms control and disarmament.

When I look back on the years I have spent jousting after the Windmills life has placed before me, summoned to the fray by a bugle I alone seemed to hear, I am struck by how futile it all has been.

I did not stop the war with Iraq.

Iran continues to be accused of pursuing a nuclear weapon, despite all evidence to the contrary.

America remains deeply infected with the disease of Russophobia.

Israel continues to commit genocide against the people of Palestine.

The Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty I helped bring into this world has been abandoned.

And, lastly, the very concept of arms control and disarmament has been betrayed by the lapsing of the last remaining arms control treaty between Russia and the United States, New START.

Like many, I seek solace by reading words of wisdom offered by the great men of history. Over time, I have been drawn to the words of President Theodore Roosevelt in what has become known as “The Man in the Arena”:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

Today I am overcome by the reality that I have spent myself in a worthy cause, failing greatly while daring greatly.

It is not a good feeling.

For a long time, I operated under the illusion that these existed in isolation, a stand-alone poem intended to inspire on its own volition.

But being possessive of a curious mind, I did the research necessary to discover that this was but an extract from a much longer presentation, a speech entitled “Citizenship In A Republic” which Roosevelt delivered at the Sorbonne, in Paris, France on 23 April, 1910—more than a year after leaving office.

Like John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address, context is everything, and Roosevelt’s speech contains much context for those willing to read it in its entirety. For example, Roosevelt’s “man in the arena” doesn’t stand alone, but rather in contrast to others Roosevelt singles out for derision and disdain”

Shame on the man of cultivated taste who permits refinement to develop into fastidiousness that unfits him for doing the rough work of a workaday world. Among the free peoples who govern themselves there is but a small field of usefulness open for the men of cloistered life who shrink from contact with their fellows. Still less room is there for those who deride of slight what is done by those who actually bear the brunt of the day; nor yet for those others who always profess that they would like to take action, if only the conditions of life were not exactly what they actually are. The man who does nothing cuts the same sordid figure in the pages of history, whether he be a cynic, or fop, or voluptuary.

It is the final words of this passage, however, which light the fires that fuel the passion for service that defines my very being:

There is little use for the being whose tepid soul knows nothing of great and generous emotion, of the high pride, the stern belief, the lofty enthusiasm, of the men who quell the storm and ride the thunder.

I have sought to quell the storm, and to ride the thunder.

And like many a bronco rider before me, I have repeatedly failed to remain seated for the requisite 8 seconds, instead tasting the bloodied dust of defeat in my mouth, and feeling the pain of bones broken by the fall.

I have spent a lifetime speaking to “men of cultivated taste” who populate the halls of power, whether in the White House, Whitehall, Quai d’Orsay, the Kirya, Karradat Mariam, or any other place where “those who deride of slight what is done by those who actually bear the brunt of the day” reside.

I have spoken until I was blue in the face and hoarse of voice.

And I am exhausted.

This last battle, to try and save the New START treaty and the principle of arms control and disarmament which it represents, has all but broken me.

The hell with the “arena.”

And the hell with “daring greatly.”

If standing tall while beaten and bruised, covered with blood and sweat shed in vain, is what a man should aspire to, then the hell with being a man.

Outcomes matter.

Service and sacrifice independent of the reward of success is simply an exercise in narcissism, making the participant no better than those who cheer him on from the sidelines.

I have written for the most influential newspapers and magazines of the day.

I have addressed the US Congress, British Parliament, the French and Italian Senates, the Japanese Diet, the Iraqi Parliament, the European Parliament, and NATO.

I have spoken before audiences in the greatest Universities of the United States—Harvard, Yale, Brown, Columbia, MIT, Georgetown, Oxford.

I have spoken before the Council on Foreign Relations, Royal United Services Institute, and Chatham House.

I have appeared on the most popular programs in mainstream American television.

This was my arena.

But my audience wasn’t composed of likeminded warriors for peace and justice, but rather those who “deride of slight what is done by those who actually bear the brunt of the day” and “those others who always profess that they would like to take action, if only the conditions of life were not exactly what they actually are.”

I am tired.

Physically, mentally, and morally.

My computer is filled with half-finished articles, because I can no longer muster the energy necessary to see these works to fruition.

Yesterday was a particularly frustrating day.

I started the morning trying to finish one article on the death of arms control, only to put it aside and begin a new article on the futility of diplomacy.

Neither were finished.

I did a series of interviews which garner, collectively, millions of views.

But at the end of each interview I was overcome by the futility of it all.

I might as well be standing on top of a remote mountain shouting into the wind.

I was scheduled to appear on a podcast, Ask The Inspector, at 7 pm.

I was not motivated, and even entertained thoughts of just cancelling the whole damn show.

Not for the night, but forever.

“Ask the Inspector”?

Who gives a damn.

Just more speaking with nothing happening.

Words for the sake of words, a literal self-licking ice cream cone of ego-driven delusion.

I picked my wife up from work, and on the way home we decided to stop by the local Taco Bell to get a bite to eat before racing home so I could be seated before my computer by 7 pm.

It was a cold night, with snow falling, and the parking lot was treacherous to walk across. As I made my way over the ice-slick asphalt, I heard a voice call out from a car parked on the other side of the lot.

“Mr. Ritter?”

I can’t say good thoughts crossed my mind—I have received death threats on social media, and a simulated letter bomb in the mail. I was warned by someone closely linked with Homeland Security not to present myself in public because of the potential for being attacked by the supporters of causes I have spoken out against—Israel and Ukraine come to mind.

I started walking toward the vehicle in order to create space between myself and my wife, whom I directed toward the entrance of the Taco Bell restaurant and away from the man in the car. I transferred my wallet, keys, and phones into my left hand, looking for a place to toss them in case I had to free up both hands to deal with some form of attack.

“Scott Ritter?” the voice called out again.

I walked up to the car, checking out the man inside and scanning for weapons and passengers.

But I was quickly distracted by the smile on this man’s face. He appeared genuinely happy to see me.

“I just finished listening to you on Nima’s show!” he shouted out. “And here you are! I can’t believe it!”

Nima Rostami Alkhorshid is the host of a podcast, “Dialogue Works”, and I had appeared on his show earlier in the day.

“I listen to you all the time!” the man said.

He got out of his car, and shook my hand.

“I love what you say”, he said, looking me in the eyes. “Keep doing what you do. It means so much to me and others.”

I thanked him, and he got back into his car.

“I’m getting ready to listen to you on ‘Ask the Inspector’”, he said. “I can’t believe it! I just listened to you on Nima’s show, and I’m getting ready to listen to you in 40 minutes, and here you are, in the parking lot of Taco Bell!”

He waved as he drove off, and headed into Taco Bell, where my meal of Diet Coke and two bean burritos waited for me.

This was not the encounter I had feared it would be—just the opposite.

His words and his demeanor awakened me from the self-pitying somnolent state I had been trapped in over the course of the past week.

And as I thought of him, his words and demeanor, I was struck that he was not alone in his appreciation of what I had been trying to accomplish.

I had travelled to New York City recently, and was trying to hail a cab when I was stopped not once, but twice, by random people on the street who recognized me and wanted to shake my hand and offer words of encouragement.

In the hotel lobby people looked over at me hesitantly, before approaching, wanting to shake my hand.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that these were not isolated occurrences, but rather a pattern of behavior which had been repeating itself for some time now.

Cab drivers in Washington, DC.

AMTRACK conductors.

Baggage handlers at airports.

Cashiers at convenience stores.

And just average Americans on the street.

These were not people “of cloistered life”, but rather the salt of the earth, those who bore “the brunt of the day.”

They were my fellow “Citizens of the Arena”, people like me who were making a stand in defense of what was important to them.

People who had been beaten down by life, but who had picked themselves up and continued the charge.

They told me how important my words were to them.

How I was a voice of sanity in an insane world.

How my words and actions gave them hope for a better world.

People who believe in the concept of “Waging Peace”.

And to a person, they all encouraged me to continue what I was doing.

They were—and are—why I fight.

My friends and family have been there for me every step of the way in this journey of struggle and turmoil that is my life.

And they have paid a horrific price for their loyalty.

If they were the only reason why I was repeatedly stepping into the arena, then logic dictates that at some point I must stop doing that which brings them pain and suffering (remember, unjust prosecutions, imprisonment, FBI investigations and raids, and de-banking don’t just impact me, but my family.)

A wise man would pay heed to the lesson of Sir John Falstaff in Shakespeare’s play, ‘Henry IV Part 1,’ in particular Act V, Scene 4:

“To die is to be a counterfeit, for he is but the counterfeit of a man who hath not the life of a man; but to counterfeit dying when a man thereby liveth is to be no counterfeit, but the true and perfect image of life indeed. The better part of valor is discretion, in the which better part I have saved my life.”

Discretion is the better part of valor, and how indiscrete is the man who would hazard his family and friends over the false pride of ego-driven “honor”?

Save the world?

What childish conceit.

Until, of course, the “world”, in the form of random citizens, urge you to continue the struggle, in order to create a better world, one worth living in.

Thus empowered, a man might look his family in the eyes and, with the kind of courage that only comes from conviction, shout “Once more into the breach!”

Figuratively, of course.

I want to thank this kind stranger who stopped me in the Taco Bell parking lot to thank me for what I was doing.

And in the process thank everyone else who has, over the years, offered words of encouragement and gratitude.

It means more than you can possibly know.

Today I have taken an oath to myself to finish the articles that sit dormant in my computer.

I will complete the list of questions I was preparing for interviews I hope to conduct in March, when I plan on returning to Russia to continue the mission of defeating Russophobia and promoting better relations between the US and Russia, between Americans and the Russian people.

I will climb once more into the arena, my face marred by dust and sweat and blood, and raise my gloved fists to my face, challenging my opponents to resume the fight.

I am not defeated.

Because I know why I fight.

And that reason is you.